BOOKS

BOOKS In Which The Universe Brought Us Keith Gessen

Monday, June 28, 2010 at 10:28AM

Monday, June 28, 2010 at 10:28AM

The Possessor

by ELENA SCHILDER

I went to see Elif Batuman read mostly because I wanted to know what Keith Gessen looked like. I guess I could have Google-image searched him, but I hate typing the names of people who are of my relative age and demographic into the Safari search field during work. It is an activity that seems, first of all, unprofessional, and second of all makes me feel like I am about to be caught. All of which is to say that I didn’t search for Keith Gessen’s image on the Internet, deciding instead to let the universe bring him to me at McNally Jackson Books.

That week I had been printing out Gessen’s archived New Yorker pieces and reading them on the subway. I read two long articles, one about the Ukrainian elections and one about the murder of a Russian journalist and the accompanying trial. I remember being genuinely charmed by Gessen’s writing, which seemed straightforwardly personal and, at certain moments, suffused with a wonderful cheekiness. I had seen Gessen’s novel All the Sad Young Literary Men in the Strand; for me, and I would assume for others, it was a book whose title promised content too close to home (my own gender notwithstanding) even to skim in a bookstore or using Amazon’s “Look Inside” function. I didn’t want to look inside.

ben kunkel, mark greif, keith gessen, marco roth

ben kunkel, mark greif, keith gessen, marco roth

That same feeling, of intimacy mixed with claustrophobia, washed over, and over, and over me when I walked into McNally Jackson for the reading. I think it was in April. I was early; the kid who served me coffee and a cookie was surly. I walked around and noticed that the store categorizes its fiction by world region, which seemed like a good idea.

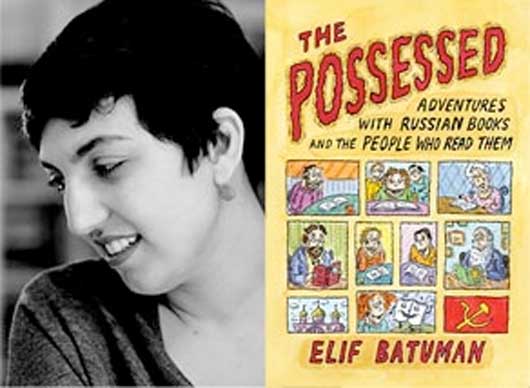

Men and women of a certain ilk – mostly alone, and therefore sort of somber – poured in. Because I, too, was unaccompanied, I began to feel prickly and oppressed by the crowd. I texted my sister: “Hell is bookish people.” Batuman’s book, The Possessed, which I hadn’t read and didn’t own at the time, but which I bought – like a sucker – at the reading, is as good as you have heard it is. Its seven essays, several of which have been published in n+1 – the publication which “discovered” her, hence Gessen’s involvement in the reading – focus on Russian literature (both classic and obscure) and its effects, explicit and implicit, on the author’s life.

The essays are set against an academic background. The relationships they explore deeply are those between teacher and pupil, grad student and grad student, and among attendees of academic conferences. They are autobiographical, but they intend to convey life as it is experienced by someone who is subsumed by texts. The book is kind of about reading one’s way through life – a trap that feels familiar to me, though I often wonder if, say, my kids will even know it was ever a possibility.

In the introduction to the book, Batuman talks about the deep ambivalence toward fiction writing that propelled her into the comp lit department at Stanford and, consequently, into the writing of a book of personal, yet analytic, essays. She describes her experience at a summer writing workshop in New England with all the sass we will come to expect of her:

I wanted to be a writer, not an academic. But that afternoon, standing under a noisy tin awning in a parking lot facing the ocean, eating the peanut-butter sandwiches I had made in the cafeteria at breakfast, I reached some conclusive state of disillusionment with the transcendentalist New England culture of “creative writing.” In this culture, to which the writing workshop belonged, the academic study of literature was understood to be bad for a writer’s formation. By what mechanism, I found myself wondering, was it bad?

Conversely, why was it automatically good for a writer to live in a barn, reading short stories by short-story writers who didn’t seem to be read by anyone other than writing students?

I think most of us who care about literature at all would agree that, with a few exceptions, those short stories derived from other short stories are unreadable, and if only for this reason, The Possessed is like an amazing cold shower. It feels at times like Batuman is washing the “craft” of writing – so exhaustively documented, taught, and debated – clean of the very idea of craft. I couldn’t think of a better answer to the New Yorker fiction section.

What results from Batuman’s inquiry into what would happen “if you went to Balzac’s house and Madame Hanska’s estate, read every word he ever wrote, dug up every last thing you could about him—and then started writing,” is a web of connections between present-day human beings – American, Russian, Uzbek, and miscellaneous others – their historical antecedents, great writers, and the characters born of those writers’ works. It’s a web that Batuman builds carefully, with both a scholar’s touch and a novelist’s imaginative power, and there are moments at which the combination feels transcendent, and like a new kind of literary experience. I don’t think it’s too much of an oversimplification to say that the book operates according to a theory of – and with a deep faith in – coincidences.

timothy archibald In the book's strongest essay, “Babel in California,” we hear Batuman exclaim, in the midst of Babel research that has drifted all the way to Merian Cooper, director of the original King Kong, “’So there really is a path from [Nikolai] Fyodorov [a Russian philosopher] to Cooper!’” To which her companion retorts, “’If there wasn’t, you would find one anyway.’” Her detective’s streak – apparent in her many references to Arthur Conan Doyle, and even more in her attempt to prove that Tolstoy was murdered – is strong and very charming in its insistence.

timothy archibald In the book's strongest essay, “Babel in California,” we hear Batuman exclaim, in the midst of Babel research that has drifted all the way to Merian Cooper, director of the original King Kong, “’So there really is a path from [Nikolai] Fyodorov [a Russian philosopher] to Cooper!’” To which her companion retorts, “’If there wasn’t, you would find one anyway.’” Her detective’s streak – apparent in her many references to Arthur Conan Doyle, and even more in her attempt to prove that Tolstoy was murdered – is strong and very charming in its insistence.

It is, however, slightly unnerving to realize that, for Batuman, seeking out unity between ideas and causality among events may trump all other projects. At the beginning of the Q & A, Keith Gessen mentioned that one of the great things about Batuman’s work is its ability to paint “grotesque” portraits of minor characters; indeed, Batuman’s cast of translators, semioticians, and egomaniacal grad students is painted with an absurdist’s brush. Watching her at the reading, it was hard not to read an edge of incredulity in almost every one of her answers – she has that air of bafflement that I’ve seen before in academics who, so comfortable among their books, seem bemused by the mannerisms and speech of almost everybody else.

I don’t mean this with even an ounce of disparagement: The Possessed is a great book and in many ways a really hopeful one, as regards the future of both academic and creative writing. But there is something about the way they merge here that, on occasion, made me nervous about the degree of alienation you would have to feel to write so thorough and artful a book about your own experience.

For example, there are pages and pages of dialogue in the book that, I believe, must have been faithfully recorded by Batuman either during, or directly after, it was spoken in real time. There is something a little off-putting about the way in which real people are ripped from their contexts and made to mock themselves on Batuman’s page. Of course, she’s not the first writer to use the technique, nor will she be the last. Her project just makes the jump from life to page a little more self-conscious – which isn’t good or bad so much as it feels odd.

Keith Gessen, it turns out, looks like a writer. Had I been given the task of dressing him for the evening, I might not have paired jeans with a wool blazer and I might have given him a haircut. He asked Batuman whether her book was a novel; when she didn’t give a satisfactory answer (and I’m not sure many of her answers satisfied him that night), he said with quiet self-assurance that he thought it was a novel. A Russian woman in the audience loudly disagreed (in Russian), which led to a colorful argument that would have found an easy place in The Possessed and which, in the ensuing weeks, helped to remind me that I might want to write about it.

Elena Schilder is a contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Abu Dhabi. She last wrote in these pages about Richard Ford. She blogs here.

"Dragonfly" - M. Craft (mp3)

"Standing in the Way of Control" - Gossip (mp3)

"I've Been Lonely For So Long" - Frederick Knight (mp3)

elena schilder,

elena schilder,  elif batuman,

elif batuman,  keith gessen

keith gessen