FILM

FILM In Which They Have Placed Jesus On The Ground

Monday, January 23, 2017 at 1:57PM

Monday, January 23, 2017 at 1:57PM

Suited to the Cloth

by ETHAN PETERSON

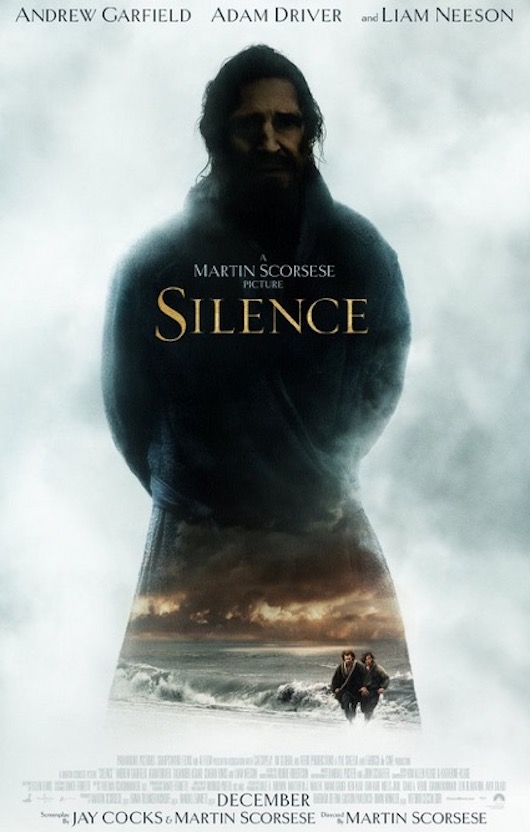

Silence

dir. Martin Scorsese

161 minutes

Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) is at his absolute best in confinement. His legs seem to only go up to the wooden bars that represent the limits of his world. Abdicating to the sun and air makes him inconsolable – his faith is best processed in private, and he does not like to be disturbed. This makes him on a surface level a decent, albeit somewhat flawed candidate for priesthood.

Sebastião Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) is at his absolute best in confinement. His legs seem to only go up to the wooden bars that represent the limits of his world. Abdicating to the sun and air makes him inconsolable – his faith is best processed in private, and he does not like to be disturbed. This makes him on a surface level a decent, albeit somewhat flawed candidate for priesthood.

His friend Francisco Garupe (Adam Driver) is much more suited to the cloth. Persecuted by various Japanese warlords/government leaders, the two separate early on in Silence, Martin Scorsese's lengthy adaptation of a novel by the Catholic writer Shūsaku Endō based on oral histories of the period. Both are driven to service the various spiritual needs of this secular country.

Scorsese shows the missionaries at work early on so we get a fairly good sense of what they are there to do. Rodrigues is forced to hold a midnight mass in a dimly light underground cavern – in many ways in Silence, we are meant to think that the mere act of worshiping God is penitence. After he is betrayed to the authorities by his guide Kichijiro (Yosuke Kubozuka), Rodrigues has much better accommodations. His hosts place him in a small cell in the middle of a village. In freedom he is forced to eat small, roasted lizards; in jail three meals are delivered to him so he may recover some solidity in the abdomen area.

Garfield is one of those performers who is convincing when he speaks but terrible at listening, which makes him a strange choice for the lead role. He seems mostly to have been selected for his resemblance to the historical Jesus. At one point he sees Jesus in his own reflection, which is either serious apostasy or serious flattery. Either way it does not take much for him to abandon his faith by stepping/falling on an image of Jesus laid on the ground – in doing so he follows in the footsteps of his mentor Ferrera (Liam Neeson).

In one scene, a Japanese convert named Monica asks Rodrigues straight up what the problem is with dying if they are all just going to paradise afterwards. It is the only scene in Silence that possesses a philosophical jocularity. It makes Rodrigues sad to think he causes the death of all the innocent people, even if indirectly, and indicates his lack of faith. The difference between he and his colleague Garupe is made manifest in an astonishing scene where Adam Driver, emaciated and disturbed, tries to save Monica and drowns himself in the effort. Rodridgues screams and cries, but never does anything to help.

Filmed in Taiwan, Silence seems perilously out of time, and that is probably why very few people even managed to view it. The film's hopeless advertising attempted to transform the project into something of a thriller, and final cut retains something of this relentless movement. Scorsese tries very hard not to indulge himself or any of the characters, and the voiceover that he does include is directly necessary to giving us a sense of how we should be processing these events.

Scorsese clearly enjoys himself the most when he can channel Kurosawa's characteristic roving angles in the village scenes. Such moments are brilliant homage, but fall a bit short of a transcendent originality. Even among its stunning sets and energizing performances, the aspects of Silence meant to reassure us we are watching something familiar and understandable end up distracting us from faith. This is a strong thematic point.

Ethan Peterson is the reviews editor of This Recording.