NEW YORK

NEW YORK In Which We Admire The Yellow Tower

Wednesday, June 13, 2012 at 11:49AM

Wednesday, June 13, 2012 at 11:49AM

Bunker or Vault

by RAPHAEL POPE-SUSSMAN

I stared at my laptop screen and a crouching, naked baby with hollow eyes and a pig’s nose stared back at me. I blinked. The baby continued staring. I closed my computer, then reopened it. The baby was still there, floating in white space, looking straight ahead.

I gave up staring at the baby and turned my eyes to the text beneath it: Idant, a division of Scientific Medical Systems, was established in 1971 as a public corporation and is a subsidiary of DAXOR Corporation. It is one of the oldest and largest semen banks in the United States. My eyes passed over the phrase “semen bank” and circled back, reading and rereading it, over and over. I had never seen that phrase before. In a sitcom, “sperm bank” would be a throwaway line, but “semen bank” is too clinical to be funny.

The doctor who had recommended Idant hadn’t used the words “semen bank.” It was a “fertility clinic,” a place to “store your sperm.” You know, just in case.

It was the winter of 2010, and I was reading the words “semen bank” in the living room of my mother’s house. If my mom had stepped away from the potato wedges on the stove, she would have seen a familiar scene: her youngest son, wearing pajamas, curled up on the same threadbare gray sofa he’d crawled on as a baby.

But she also would have seen my bald head and known that this scene wasn't familiar at all. Three weeks earlier, I’d been diagnosed with testicular cancer.

I had visited the oncologist that morning, and he’d given me two instructions to prepare for treatment. I should shave my head immediately, he said — better to do it now than to wait for chemo, when it comes out in clumps. I’d sat on a chair in the bathroom, shirtless and shivering, while my brother ran a pair of clippers along my scalp. I had dreaded that haircut, but when I had finally rallied the courage to look at myself in the mirror, I wasn’t shocked by what I saw. There was the same thin, pale face with high, jagged cheekbones; it looked harsher and quite worn, but it was still mine.

The oncologist had saved his second instruction for the final minutes of my visit. “After chemo, you’ll have a retroperitoneal lymph node dissection,” he’d said. “It’s a major surgery, but it knocks the rate of recurrence below five percent. The biggest risk is infertility—for you, the chances are ten to twenty percent. You’ll want to bank your sperm.”

I had only half-grasped what he was saying. I’d been sitting in his office for more than seven hours, during which I’d been relentlessly barraged with statistics, drug names, dietary restrictions and requirements. I would need four different drugs to control the vomiting, two to regulate my bowel movements, and others for acid reflux, dry skin, anxiety, and depression. I could look forward to constant nausea, dizziness, cognitive impairment, ringing in the ears, numbness in the fingers and toes, kidney failure—only death went unmentioned.

At home that night, I had opened my computer and Googled “Idant.” That’s how I came to be staring at a picture of a naked baby with the nose of a pig and an eerie, unblinking gaze.

Idant pioneered semen banking in the U.S. and developed the technology that made it possible to ship frozen semen all over the world. Today, Idant maintains one of the largest human semen banks in the U.S. and provides services to the medical community throughout the world.

I liked the idea of my sperm being a part of “one of the largest human sperm banks in the world.” It would be like having my monograph in the Library of Congress.

I picked up the phone and dialed the number for Idant. No one answered, so I left a message. “Hi, my name is Raphael Pope-Sussman. I need to make an appointment immediately,” I said. I paused, then added: “I have testicular cancer — I was referred by Dr. George Bosl.” I had to make sure the person checking the messages at Idant understood I wasn’t just some guy who frequently goes to sperm banks to jerk off. It’s like explaining to the cable guy that your apartment is a mess because you’ve been really busy at work. You feel like you have to do it. But the cable guy doesn’t care. He’s just there to fix the TV.

The next morning, a woman from Idant called. She offered me a late-afternoon appointment for the coming Saturday. “That’s perfect,” I said. “Do I need to bring anything?”

“Just your insurance card. And don’t have sex or masturbate before you come in.”

I had imagined Idant as a sleek storefront with glittering glass windows and polished white walls. I would walk in, as one walks into an eyeglass shop, and an attractive female attendant in a lab coat would lead me into a waiting room in the back. This scene was entirely an invention — the only sperm banks I’d ever seen were in movies, which always show the waiting room, but never the exterior. I’d never actually heard of someone going to a sperm bank.

Idant’s website listed an address on Fifth Avenue, just a block from Herald Square. I got off the train at 34th Street and walked east, scanning the street for the lab. The sidewalk was bustling with tourists and shoppers loaded down with overflowing bags. I weaved my way through the maze of puffy coats, past a dusty, rundown clothing store I’d never heard of, several cell phone dealers, Old Navy, Foot Locker, a Payless outlet. Nothing resembled a medical facility or a lab.

In front of Macy’s Herald Square, I stopped and scanned the area. Traffic clogged the street and cabbies honked furiously, playing the perpetual, dissonant tune of Midtown at rush hour. The whole neighborhood looked wrong. These streets were all commercial. Every storefront was for a chain store. The buildings were old and squalid, not right for an ultramodern sperm bank.

I started to sweat. This was the last appointment of the day. If I missed it, I couldn’t reschedule. It was Saturday, and I was starting chemo Monday. There was no flexibility on the date.

My heart jerked into gear and I broke into a run, darting between stopped cars and dodging pedestrians. At the next corner, I stopped again. There was no point in running if I had no idea where I was headed.

I crouched and cradled my head in my hands. Why was my mind failing me? I hadn’t even begun chemotherapy yet, and already a fog had descended. I couldn’t do something as basic as find an office building on a gridded street in the city in which I’d lived my whole life. How could I endure these months of treatment, which my oncologist had made clear would be the most agonizing, exhausting, miserable months of my life, if I couldn’t manage what amounted to a simple errand?

I felt a tap on my shoulder. I looked up and saw a tall, thin man with wavy brown hair and horned-rim glasses. “You all right there?”

I got to my feet. “Yeah,” I said, swallowing hard to hold back tears. “I was supposed to go to a doctor’s appointment at 350 Fifth Avenue, but I’m completely lost.”

The man laughed and pointed at a building across the street. “You can’t miss it,” he said. “That’s the Empire State Building.”

The first time I visited the Twin Towers, at the age of five, I felt smaller than I ever felt before or since. Staring at the soaring edifices, I wondered how many millions of me it would take to fill the buildings’ vast lobbies, and how many houses I’d have to stack to reach the top. Set back from the cityscape in a cavernous plaza, the buildings seemed to rise out of nothing and extend beyond the sky. To view the Twin Towers from their bases was to be lost in dizzying infinity.

The Empire State Building, viewed from its base, is considerably less impressive. For a building of its stature — physical, architectural, or historical — it’s quite easy to miss. The deep setbacks, which give the building its distinctive appearance on the skyline, conceal much of the tower from street level. If you’re standing in its shadow, you might mistake it for an anonymous office building of twenty-five stories. You can walk right past the Empire State Building, or even wander into one of the shops on the ground floor, and never have an inkling of the structure that rises above you.

In the lobby of the building, I approached a maroon-clad attendant. “Uh, is this 350 Fifth Avenue?” I asked hesitantly. The attendant raised his eyebrows: “Yes, that’s the address. You’re in the Empire State Building.” So the man had been right. But there had to be a mistake. The Idant website had said nothing about the Empire State Building. Isn’t that something you’d want to mention? And why would you put a sperm bank in the Empire State Building? That’s an obvious terrorist target. The sperm bank that serves my sperm should be somewhere safe, like a bunker in Montana or a locked vault. You wouldn’t store the Hope Diamond in the window at Tiffany’s. That’s just not safe.

“I’m looking for Idant Laboratories,” I said.

“What’s that? I’ve never heard of that,” the attendant said. He called out to another attendant, a woman, also in a maroon uniform: “Hey Maria—you heard of any ‘Idant’?”

The woman shook her head.

“Are you sure?” I asked. “Idant — it’s a, uh, sperm bank.”

“Oh, the sperm bank. Of course! Maria, he means the sperm bank!” A group of tourists had been milling about the lobby and they turned and stared at me. “Yes, just step down to the elevators, sir,” he said. “You’ll want the seventy-first floor.”

I’d expected the inside of the Empire State Building to be palatial — wide corridors, marble floors, and ornate fixtures. But the seventy-first floor was cramped and dirty, like a back hallway in a run-down apartment building. The door to Idant Laboratories was windowless and painted in a blinding shade of insane-asylum white. I rang the bell and stood back, nervously tapping my toes on the cheap grey tiles. The door clicked, and I pulled the handle, straining to move the heavy steel. Whatever was inside, it was certainly well secured.

What I saw on the other side of the door bore no resemblance to the sperm banks I’d seen in movies. No waiting room, no attractive nurses, no guys sitting nervously. It was just me and a rotund balding man in a stained lab coat.

The man was perched on a high chair inside a room full of filing cabinets and racks of lab equipment — test tubes and flasks and beakers. He eyed me from behind a square glass window, like the agent at a ticket booth. I said I had an appointment. “You’re late,” he said, sliding a pile of papers through a gap at the bottom of the window. I nodded apologetically.

“When was the last time you masturbated or had sex? Was it more than a week ago?” he asked accusatorily. I told him that yes, it had been more than a week. He looked unimpressed.

When I’d finished filling out the forms, the man pulled out a small white cup, which he placed in the palm of my hand. “There you go. You’re just around the corner: Room 2.”

Room 2 resembled the examination room at my pediatrician’s office. There was the same exam table with the green vinyl upholstery, the same fluorescent lighting, the same grime-covered white walls. There was the same magazine rack, built of flimsy grey particle board and stuffed with beat-up magazine back issues—now Hustler instead of Highlights. An old TV-VCR unit was mounted on the wall, and below it stood a plain wooden bookshelf that held a small collection of pornographic films.

How many guys had masturbated in that room? Thousands, maybe tens of thousands? Every surface was a potential resting place for millions of slaughtered sperm. I shuddered at the thought and scurried to the center of the room.

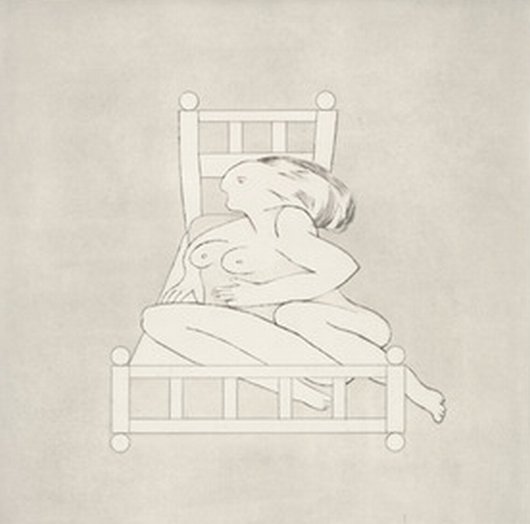

Moving hesitantly, I unbuckled my belt, fumbled with a few buttons, and pushed down my pants. My penis was shrunken and flaccid. I kneaded it with my hand, trying to get the blood flowing, but it just hung there, exhausted and ambivalent. It’s not easy to become aroused when you’re filled with revulsion and it’s cold and you’re alone and terrified. There’s nothing erotic about masturbating into a cup.

Masturbation is the quintessential juvenile activity. When we masturbate, we arouse ourselves with fantasies, with imagined scenes that are unreal and impossible. In these fantasies, as in the pornography that both imitates and drives them, we think only of ourselves and act only for ourselves. To masturbate is to be again a child, perfectly solipsistic, unaware and unburdened.

But there was nothing childlike about that moment. Standing in the middle of a room full of pornography, my pants at my ankles, preparing to masturbate into a cup: this was the first glimpse I had of adulthood.

Below me was the semen-covered floor and seventy more like it, though likely not semen- covered, and the city where I was born and raised, and where I went to college. My family and friends were down there, old teachers, my classmates. And on seventy-one, in that foul room, was me, and inside me a tempest of cells dividing, and in my hand a little white cup.

I was twenty-two. At twenty-two, most people plan a few months in advance, if they plan at all. With the white cup in my hand, I was planning years in advance, perhaps decades. Ahead of me lay months of being much sicker. I would vomit bile and blood. I would be raced to the urgent care ward at 3 a.m., so dehydrated I could barely stand. I would be sliced open like a fish. I would be denied drink for days and food for weeks.

Every night I would find myself slumped on the bathroom floor, my cheek pressed against the tile. That tile at the base of the toilet smells of dirt and urine and human hair, but it’s solid and smooth and cool. I would learn to love that tile.

I could never have imagined what those months would be like. But the white cup meant something would come after; that after this ordeal was over there would still be the rest of a life, the rest of a life for which I was freezing my sperm. I would have to pass those months of illness, and afterwards, I’d be responsible for determining the contents of that something,

With the white cup, I found myself staring far into the distance. Like the five-year-old boy first setting eyes on two endless towers, I was lost, for a moment, in dizzying infinity. I was sick and I was alone. My mom might hold my hand as I lay in a hospital bed, platinum dripping into my veins and wreaking havoc on my stomach. But she could not vomit for me, endure my blinding migraines or lie in my place on the operating table. I would have to suffer for myself.

In the coming months, though I would have dozens, perhaps hundreds, of people around me, I would be absolutely alone, as alone as a guy with no pants on, in a windowless chamber in a tower in the sky.

When I was first diagnosed, I had marked the date of my final surgery on my calendar. I’d imagined that date as an ending. My scar would heal, my hair would come back, and life would return to normal. I would be free to walk the streets, healthy and strong and relieved from the myriad anxieties and neuroses that have plagued me for as long as I can remember.

But there would be no discrete ending. I would suffer the brutality of chemotherapy and surgery and the crueler fate of a slow recovery. Many nights after surgery, I would lie in bed unable to sleep, my stomach aching with gas pains, my scar aflame. Sometimes, I would hear the sound of mice scuttling in the ceiling, and I would feel them on my back and face. I would become convinced I was losing my mind. I’d tear at my hair and moan that I was dying.

I had experienced panic attacks before. The summer after surgery, as I was slowly regaining my strength, the panic attacks would arrive daily. I was training myself to breathe and eat and walk fully upright again. I knew I should be overjoyed to once again have access to these essential ingredients of life. But I was tired. A long illness runs like a river, slowly grinding down everything in its path.

For a year after my surgery, I had monthly checkups at the hospital. Now, I go every three months. During my most recent visit, I stopped in at the clinic where I got my treatment. All the nurses gathered around, chattering about how different I look with a full head of hair and color in my cheeks and a little meat on my bones. It felt a bit like ten Jewish mothers had descended upon me at once.

“You’re still the worst patient we’ve ever had with the vomiting,” they reminded me. “When the guys in here get sick, we tell them about you, how we had this one patient who could not stop vomiting, just like a fire hose.”

I grinned and shrugged. “Excellent vomiter” doesn’t quite fit on a résumé, but it's nice to be the best at something.

After my checkup, I stepped out onto First Avenue, and headed south. Moving briskly, I walked through the growing crowds, until the sidewalk was thick with bodies and I found myself pushing through the horde.

At 34th Street, I turned west, and as I walked, I lifted my gaze up toward the buildings above, scanning the sky for a familiar sight. When it came into view, I stopped for a moment on the street corner. I craned my neck and stared, admiring the yellow tower, bathed in the receding glow of the evening sun.

I looked back at the bustling street in front of me — the throngs of shoppers and businessmen, the sea of honking cabs — and I continued on my way, passing right beneath the Empire State Building, all 102 stories of it, and beneath a windowless white room in a dingy old lab on the seventy-first floor.

Raphael Pope-Sussman is a contributor to This Recording. This is his first appearance in these pages. He twitters here.

Photos by Leonard Sussman.

"My Love Is Winter" - The Smashing Pumpkins (mp3)

"Glissandra" - The Smashing Pumpkins (mp3)