BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Suffer Through A Rare Constellation Of Events

Friday, March 13, 2015 at 10:00AM

Friday, March 13, 2015 at 10:00AM

Your Letter Which I Read With Greatest Concern

The light cast by substantive references, illusions and details.

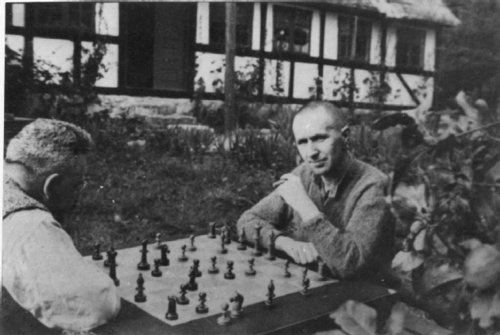

Gershom Scholem had fled Germany when things started to get complicated. He begged his friend Walter Benjamin to join him in Palestine where, he argued, they would be safe from whatever was going to happen. Benjamin constantly demurred - instead he fled to Paris, while making arrangements for his vast library to be cared for in his absence. Soon, his brother Georg had been imprisoned at a concentration camp at Sonnenburg. (He later died at the last concentration camp to be liberated by the Allies at Mauthausen.) Scholem's advice to Benjamin therefore seems prescient even at the time it is being delivered. But Walter Benjamin had other things on his mind.

The following abridged letters to Scholem relate his growing desperation at this perilous time.

Gerhard,

I'm using a quiet hour of deep depression to send you a page once again. The immediate occasion is receipt of your utterly remarkable article, which I received only this morning from Kitty Marx from Koenigsberg, along with your letter of introduction and the announcement of your arrival. The rest of the day was taken up with work and the dictation of a radio play, which I must now send in, in accordance with a contract the better part of which has long been fulfilled and which facilitated my flight to the Balers.

The little composure that people in my circles were able to muster in the face of the new regime was rapidly spent, and one realizes that the air is hardly fit to breathe anymore - a condition which of course loses significance as one is being strangled anyway…

Publication of my work has now been suspended for more than a fortnight.

Prospects of seeing the work published as a book are minimal. Everyone realizes that it is so superb that it will be called to immortality, even in manuscript form. Books are being printed that are more urgently in need of it.

Walter

Gerhard,

My constitution is frail. The absolute impossibility of having anything at all to draw on threatens a person’s inner equilibrium in the long run, even one as unassuming and as used to living in precarious circumstances as I am.

Since you wouldn’t necessarily notice this if you were to see me, its most proper place is perhaps in a letter. The intolerability of my situation has less to do with my passport difficulties than with my total lack of funds. At times I think I would be better off if I were less isolated.

The odd letter now and then gives me hope that acquaintances might put in an appearance, although experience of course teaches me not to put great faith in their plans.

Walter

Gerhard,

Regarding my condition, I am once more again lying sick in bed, suffering from a very painful inflammation in the leg. Doctors, or even, medicine, are nowhere to be found here, since I am living totally in the country, thirty minutes away from the village of San Antonio. Under such primitive conditions, the facts that you can hardly stand on your feet, hardly speak the native tongue, and in addition even have to work, tend to bring you up against the margins of what is bearable. As soon as I have regained my health, I will return to Paris.

It hardly needs to be stated that I am facing my stay in Paris with the utmost reserve. The Parisians are saying: “Les emigres song pies que les boches” (“The émigrés are worse than the Krauts”) and that should give you an accurate idea of the kind of society that awaits one there. I shall try to thwart its interest in me the same way I have done in the past.

Please write me if you have read Wiesengrund’s Kierkegaard in the meantime.

Walter

Dear Gerhard,

Even if these wishes arrive far too late for Rosh Hashanah, they will at least reach you in time for the long-sought and now official establishment of your academic duties, not to mention the title of Professor.

Before I touch on this or anything else from our last exchange, let me just sketch out my situation. I arrived in Paris seriously ill. By this I mean that I had not recovered at all while on Ibiza, and the day I was finally able to leave coincided with the first in a series of very severe attacks of fever. I made the journey under unimaginable conditions, and immediately after my arrival here, malaria was diagnosed. Since then, a rigorous course of quinine has cleared my head.

Friends have transported the major part of my archives to Paris, at least the manuscript section. The Heinle papers are the only manuscript material of any importance still missing. The problem of securing my library is mainly a question of money, and that by itself presents a formidable enough task. Add to this that I have rented my Berlin apartment out furnished and cannot simply remove the library, which is an essential part of the inventory. On the other hand, the person renting it only pays what the landlord demands.

Whether or not I will be able to move into the quarters Frau von Goldschmidt-Rothschild promised me has become rather problematic because of a series of oversights and delays far too complex to recount here. It is also gradually becoming clear that the apartment is by no means free of charge.

Walter

Dear Gerhard,

The 15th of December is drawing near, and after this date the grapes of the press will be hanging even farther out of reach for an old fox like me, and what little fruit still beckons from over the shard-strewn walls of the Third Reich has to be snatched away with the nimblest of bites indeed. I had to select this shabby stationery in order to keep the narrow temporal frame set for my letter in front of me in spatial terms. And I could say a great deal more. If I could present things to you as they truly are, I would most certainly not need to ask you to pardon my longish silence: you would understand.

But, as matters stand, I can only allude to things and say that someone who was a close acquaintance of both Brecht and myself in Berlin has fallen into the hands of the Gestapo. He was freed after someone from the same circle of friends intervened, and he subsequently turned up here and filled us in about the dangers threatening the few who are still close to us.

All this is complicated in the most fateful way by the fact that we may one day have to face the possibility that the denunciations originated from a man in Paris we all know.

Walter

Dear Gerhard,

Even though you haven’t written for quite some time, I want to return the cordial wishes you so regularly send me for Rosh Hashanah on the threshold of the European New Year. But you will have to take into account my profound weariness with the moment. For some time now, these moments have turned into days and the days into weeks. It’s not surprising that the pressure to put three new irons in the fire daily should lead to severe fatigue. I am not achieving much in my dejected state because I am convinced that I cannot ask very much more of myself.

The top priority among the little I am still capable of would probably be a change of scenery. Paris is much too expensive, and the contrast with my previous stay here is much too harsh. I see nothing encouraging when I survey my surroundings, and the only person I find of interest finds me less so.

Otherwise the town seems dead to me now that Brecht is gone.

He would like me to follow him to Denmark. Life is supposed to be cheap there. But I am horrified by the winter, the travel costs, and the idea of being dependent on him and him alone. Nevertheless the next decision I can bring myself to make will take me there. Life among the emigres is unbearable, life alone is no more bearable, and a life among the French cannot be brought about.

Walter

Dear Gerhard,

I am writing to you with unaccustomed promptness and in a unaccustomed form. I do not want to fail to make use of the rare constellation of events that puts a typewriter at my disposal, the more so since your letter of the 19th of this month as already preoccupied me.

Intensely and sorrowfully. Is our understanding really threatened? Has it become impossible for such an expert on my development as you are, an expert on almost all the forces and conditions influencing this development, to keep up to date? Do you and I stand in danger of your interest one day taking on the color of pity?

A correspondence such as we maintain is, as you know, something very precise, but also something calling for circumspection. This circumspection by no means precludes touching on difficult questions. But these can only be treated as very private ones. To the extent that this has happened, the letters in question have definitely been filed - you can be sure of that - in my “inner registry.”

Walter

"Thornfelt Swamp" - Gareth Coker ft. Tom Boyd (mp3)

"The Spirit Tree" - Gareth Coker ft. Aeralie Brighton (mp3)

gershom scholem,

gershom scholem,  paris,

paris,  walter benjamin

walter benjamin