ART

ART In Which We Expect To Find Some Kind Of Horror At Its Core

Friday, March 15, 2013 at 10:15AM

Friday, March 15, 2013 at 10:15AM

Precious Objects

by RYAN LINKOF

Entering the neatly hung gallery at Regen Projects in Los Angeles, which features the most recent series of photographer Catherine Opie, I felt a bit as if I were Dorothy entering Mombi’s cabinet of curiosities. Granted, Opie’s subjects did not appear to have been decapitated before they were frozen behind a plane of glass, but the subterranean presence of strange and unspeakable acts was heavy in the room.

Every subject is given the attention of a precious and singular object with mystical significance – each figure embedded in an inscrutable allegory, or engaged in an esoteric ritual. What is it that Kate and Laura are whispering about in the near-life-size portrait of the same name, one dressed in a flowing white dress, the other in the process of stitching what appears to be a smear of blood? I hate to be excluded from gossip, especially when it is taking place on so monumental a scale. Opie’s work has always engaged with notions of community and belonging, but never have the terms that define that community seemed to perplexingly obscure.

Opie’s aloof subjects are accompanied by even more aloof landscapes – mere smudges of synthetic pigment that only vaguely reference real physical spaces. The contrast is stark: the tautly wrought portraits, with faces and bodies conjured in unflinching detail are quite distinct from the hazy, unfocused landscapes, intentionally blurred so as to leave only the impression (and a faint one at that) of real Southern California parks and recreational spaces. This blurring accentuates the painterly qualities of the prints, placing an emphasis on visual sensation and response. This is not a clearly defined and knowable “Nature,” but a sublime and aestheticized world charged with symbolic meaning.

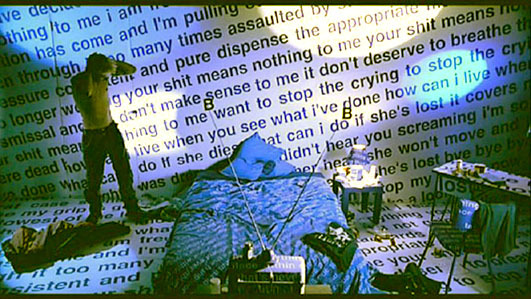

All of this opacity – this deliberate distancing from her subjects – is a departure from Opie’s documentary approach. The matter-of-fact deadpan of her earlier images of transgender men and women, mini-malls, and freeways has been replaced with a more mannered focus on psychology. Whereas much of her early work emphasizes external appearances and outward manifestations of identity, these works are much more about aspects of the self that lie below the surface. As viewers, we are confronted with a series of downcast eyes, or glazed-over stares. I had gotten used to seeing Opie’s subjects staring defiantly back at the camera, but at Regen, a mere four of the twenty portraits feature subjects who return the viewer’s gaze – the rest seem to be caught in trancelike thought.

The blankness of the subjects’ stares is mirrored in the blankness that defines them in space. The portraits are notable for the inky background that functions as a kind of void, eliminating perspective and spatial depth. The stark, chiaroscuro lighting heightens attention on the bodies caught in the frame and makes them seem both naturalistically rendered and insistently artificial. This cavernous black expanse is in sharp contrast to the bright candy-colored backdrops so characteristic of her previous portraiture, and hints at Opie’s attempt to explore the recess of her subjects’ inner lives.

The works up at Regen offer plenty to make the studious art history geek smugly content. The baroque color palette of the prints – with their heavy blacks and dramatic, stagey lighting – evokes seventeenth century painting, in the mode of Caravaggio. Dramatic oval frames and to-scale full length portraits resemble the weighty portraiture of Holbein and Van Dyck, relying on conventions of representation and display that have long been out of vogue. Even the choice to exhibit landscapes and portraits together – the favored genres of early modern and nineteenth century bourgeois interiors – looks backward to earlier modes of representation and exhibition. The thick sense of history only accentuates the feeling that one has entered a foreign, and perhaps even forboding, world.

One of the qualities that makes Opie’s work so exciting is the element of violence and danger that awaits us as we make our way through her photographs. This series is no different. Evidence of physical violence – experienced as fetish ritual, as in the visceral work Friends, which shows a woman having her mouth sewn shut, or an act of nature, as in the jelly fish stings seared into Diana Nyad’s flesh – obtrude into otherwise exquisitely pleasing imagery. Still feeling a bit like Dorothy, I advanced through the gallery expecting to find some sort of horror at its core.

It is this ability to introduce incongruous and jarring moments of bodily pain that makes Opie’s work powerfully subversive, despite its seemingly conventional stylistic mode. She shares much with Robert Mapplethorpe, an artist that influenced Opie when she was an art student, as she harnesses photography’s allure in the service of a politics of the body. She has the rare ability, in her words, to “seduce the viewer into considering work that they might not normally want to look at…to draw the viewer in through the perfection of the image.” Many of these works are very near perfected images. Consider me seduced.

Ryan Linkof is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer living in Los Angeles. He is the Ralph M. Parsons Postdoctoral Curatorial Fellow at LACMA. He has published in a number of online and print publications, including Photography and Culture, Media History, the New York Times and LACMA's Unframed blog. You can find his tumblr here.

catherine opie

catherine opie

"Dandelion" - Dorena (mp3)

"A Late Farewell" - Dorena (mp3)