The Beauty Myth

by RACHEL SYKES

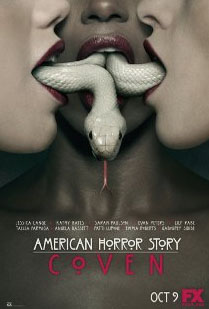

American Horror Story: Coven

creators Ryan Murphy & Brad Falchuk

Witches are malicious, or so we’re told, in the pursuit of youth and beauty. And for witches, who, on film, must always be beautiful, there is no greater threat than the co-existence of the young. Youth reminds the beautiful that their time, if not over, is pending. So when Coven, the third incarnation of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story, opens in Louisiana in 1834, we don’t bat an eyelid as Madame LaLaurie (Kathy Bates) rubs the blood of a virile young slave across her face, claiming that their pancreas diminishes the waddle of her neck. In the present day, we don’t flinch when Fiona Goode (Jessica Lange), the greatest witch of her generation, experiments on monkeys and sucks the life force from a young scientist. It’s of no great importance, killing in the name of beauty - it’s what witches, what all women, ideally would do.

Witches are malicious, or so we’re told, in the pursuit of youth and beauty. And for witches, who, on film, must always be beautiful, there is no greater threat than the co-existence of the young. Youth reminds the beautiful that their time, if not over, is pending. So when Coven, the third incarnation of Ryan Murphy’s American Horror Story, opens in Louisiana in 1834, we don’t bat an eyelid as Madame LaLaurie (Kathy Bates) rubs the blood of a virile young slave across her face, claiming that their pancreas diminishes the waddle of her neck. In the present day, we don’t flinch when Fiona Goode (Jessica Lange), the greatest witch of her generation, experiments on monkeys and sucks the life force from a young scientist. It’s of no great importance, killing in the name of beauty - it’s what witches, what all women, ideally would do.

It’s been two decades since Naomi Wolf voiced similar concerns in her first book, The Beauty Myth. Despite the growing freedoms that women had experienced over the century, Wolf claimed that the pressure to reach exacting standards of physical beauty had continued to grow. Society, she wrote, “really doesn’t care about women’s appearance per se. What genuinely matters is that women remain willing to let others tell them what they can and cannot have.” Standards of beauty would continue to be unachievable because they grow with each freedom women receive. The myth of beauty is so damning, then, not only because it matters so little to the patriarchy, but because it is enforced by women themselves.

This idea is blindingly apparent in Murphy’s all or nothing handling of witchcraft. The pilot forces young and the old together under one roof - Lange’s terrifying Fiona is the Grand Supreme, the strongest witch of her age, who returns to Miss Robichaux’s Academy for Exceptional Young Ladies to reconcile with her daughter, Cordelia (Sarah Paulson). The Academy, we’re told, was purchased by a proto suffragette in the 1860s, who would train sixty girls at a time to master their powers. Unlike the almighty Supreme, most witches only get one trick: Queenie (Gabourey Sidibe) is a human Voodoo doll, Madison (Emma Roberts) has the power of telekinesis, Nan (Jamie Brewer) is clairvoyant, whilst poor Zoe (Taissa Farmiga) can only shag people to death.

Unlike the days of old, however, when clever witches escaped northern persecution by running to New Orleans, these witches are dying out. The genetic line is breaking as families choose not to procreate and those witches unlucky enough to be born in the sticks are burnt at the stake. A sense of persecution is rife even before splits are revealed within the world of witchcraft itself. From the second episode, Fiona is at war with voodoo queen Marie Laveau (Angela Bassett), who has kept the murderous LaLaurie prisoner for 180 years and uses an immortality potion that Fiona is now set on obtaining. In the place of solidarity, it seems, there is a battle for youth and beauty.

As the Supreme takes on the education of young girls, she is contrarily engaged in the fight to retain her own youth. In interviews, Lange has identified the Dorian Gray effect as Coven’s central theme: “What do you trade off for this idea of eternal youth and beauty and how much are you willing to sell for that? How much of your soul are you willing to give up?” But if Lange frames the series as a conflict between self and soul, Murphy seems more interested in how many other souls we might sacrifice. As is transparent through most of our fairy tales, and reinforced by Wolf’s idea of the beauty myth, these women might be under threat, but they are of the greatest danger to each other.

In this way, Coven functions as a grand old metaphor for feminism. The academy is founded by a suffragette, for a start, and we’re told that the line of witches is under threat, that their public visibility has waned as witches got too scared or too comfortable to protest their persecution. Fiona’s daughter, Cordelia, is the mediator: she thinks the fight is over and teaches her pupils to make do and get by.

Fiona, however, is the radical. Leading the girls on an impromptu “field trip” through the streets of New Orleans, she praises an alternative coven, a radical splinter group, who in the 1970s were proud and public in their defence of their group. In the fight between voodoo and witchcraft there’s even an intersectional split when Fiona describes Laveau’s voodoo magic as the “nail” to witchcraft’s “hammer”.

From this conceptual jump off, Coven deploys some brazenly literal reversals of power. Murphy neatly flips the patriarchy by creating a show full of women where men are pretty much ineffectual. When Madame LaLaurie tortures slaves, it is only male bodies that she mutilates. This is in contrast to the real LaLaurie, who committed similar crimes in the 1830s, but who primarily tortured women. Every guy Zoe sleeps with swiftly dies of an aneurysm. When Madison is raped at a party she kills a bus load of frat boys with a flip of her finger. The school’s male butler seems nice enough, but is missing a tongue. In Coven, men are the subjugated, and they don’t get the time to speak, let alone practice magic.

Ruled by supernaturally powerful females, Coven seems more fun, between atrocities, than either previous season of American Horror Story. However, the same reversal of power is less effective when it’s applied to the issue of race. Madame LaLaurie, a real life serial killer, is captured by a group of slaves seeking revenge for her crimes. In the present day, to complete the reversal of roles, LaLaurie is then forced to be a slave for Queenie. Look through enough of the show’s promotional imagery and it becomes clear that almost everything within the coven is literally black and white. After Fiona’s arrival, the group dresses only in black, starkly contrasted to the pure white of the house. Even the opening credits, already shot in monochrome, show a group of hooded figures, dressed all in black, approaching a blonde girl like an inverse Ku Klux Klan.

This switch, like Coven’s entire engagement with slavery, is both well intentioned and massively uncomfortable. It seems problematic that Queenie, the only African American in the coven, is unable to feel pain because this claim was once made in defence of slavery. LaLaurie’s brutal and extensive torturing of her slaves is not only unpleasant, it also makes little sense. Keeping her slaves tied up and mutilated in an attic fetishizes the cruellest aspects of slavery, isolating the violence perpetrated by slave owners from the economic purpose of owning slaves in the first place. The conceptual overload of American Horror Story is also kind of its charm, but the number of atrocities per act doesn’t leave enough time to work through the problems of representation in an issue this complex.

It seems either fortuitous or unfortunate, then, that the show should premier in the same week as critics write in praise of Steve McQueen’s Twelve Years a Slave. Widely celebrated for its dramatic merits, the key debate seems to be whether slavery should be represented on film at all.

Speaking about the film on NPR, the historian David Blight suggested that representing slavery is so problematic because we like narratives of progress too much. Audiences, he says, want a pleasing story, and in the case of slavery, not only are the details unpleasant, but “you have to work through to find your way to something more redemptive.” This too seems to be Coven’s narrative impasse. Flipping the roles of men and women, slave and owner, defining everything in black and white, is a neat enough trick. Yet it does little to nuance the portrayal of oppression or to articulate how it feels.

Rachel Sykes is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Nottingham. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here and twitters here. She last wrote in these pages about Showtime's Masters of Sex.

"Don't Mess With Karma" - Brett Dennen (mp3)

The new album from Brett Dennen is entitled Smoke and Mirrors, and it was released on October 22nd.

TV

TV  Friday, March 10, 2017 at 11:10AM

Friday, March 10, 2017 at 11:10AM