FILM

FILM In Which Harold Pinter Changes Marcel Proust

Tuesday, August 23, 2011 at 11:19AM

Tuesday, August 23, 2011 at 11:19AM

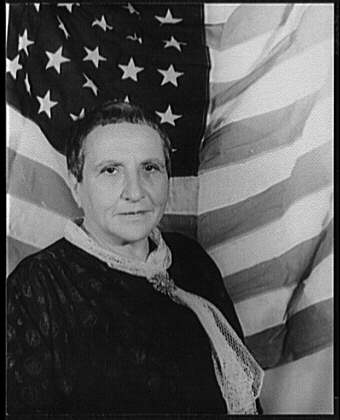

Judge of Proust

by ALEX CARNEVALE

Proust is completely detached from all moral considerations. There is no right or wrong in Proust nor in his world.

- Samuel Beckett

When Harold Pinter's screenplay of Proust's In Search of Lost Time was published in 1978, the playwright's lifetime ignorance of his critics softened. He paid attention to what they wrote because what he made was not entirely his own, and since Proust was no longer living to judge his adaptation, he was prepared to be crucified by the man's inheritors.

1972 had been a year of reading and writing in fits and starts. He worked with Beckett's mistress/scholar/translator Barbara Bray, whose knowledge of Proust's opus far exceeded his own. Pinter had only read Swann's Way, so the first idea to adapt the novel to the screen consisted of Swann's Way as the entire movie, with allusions to a larger whole. Pinter and Bray rejected this limitation immediately, and his dismissal of Swann's Way was wise — many of the events of the book simply don't revolve enough around Marcel for a drama.

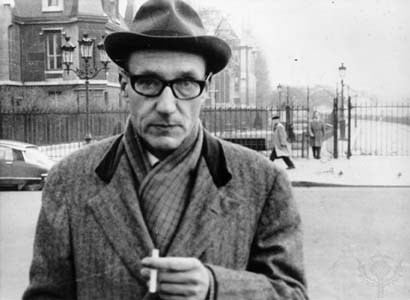

with Vaclav Havel a year before the Velvet Revolution

with Vaclav Havel a year before the Velvet Revolution

For the most part, Pinter views In Search of Lost Time as a comedy. In The Guermantes Way Proust recalls his visit to the home of Charlus, an emotional scene where the comic aspect is largely ironic. Pinter brings it out into the open:

INT. BARON DE CHARLUS' HOUSE. THE BARON'S ROOM. NIGHT.

Charlus, in a Chinese dressing gown, throat bare, is lying on a sofa.

The Valet shows Marcel into the room and withdraws.

A tall hat, its top flashing in the light, sits on a cap on a chair.

Charlus stares at Marcel in silence.

MARCEL: Good evening.

No reply. The stare is implacable.

May I sit down? Silence.

CHARLUS: Take the Louis Quatorze chair. Marcel sits abruptly in a Directoire chair beside him. Ah! So that is what you call a Louis Quatorze chair! I can see you have been well educated. One of these days you'll take Madame de Villeparisis' lap for a lavatory and goodness knows what you'll do in it. Pause. Sir, this interview which I have condescended to grant you will mark the end of our relationship. He stretches an arm along the back of the sofa. Since I was everything and you were nothing, since I, if I may state it plainly, am a prodigious personage and you in comparison a microbe, it was naturally I who took the first steps towards you. You have made an imbecilic reply to what it is not for me to describe as an act of greatness. In short, you have lied about me to others. You have repeated calumnies against me to others. Therefore these are the last words we shall exchange on this earth.

Pause.

MARCEL: Never, sir. I have never spoken about you to anyone.

CHARLUS: You left unanswered the proposal I made to you here in Paris. The idea did not attract you. There is no more to be said about that. But that you did not take the trouble to write to me shows that you lack not only breeding, good manners, sensibility, but common or garden intelligence. Instead, you prove yourself despicable in speaking of me disrespectfully to the world at large.

MARCEL: Sir, I swear to you that I have said nothing to anyone that could insult you.

CHARLUS (with extreme violence): Insult me? Who says that I am insulted? Do you suppose it is within your power to insult me? You evidently do not realize to whom you are speaking. Do you imagine that the envenomed spittle of five hundred little gentlemen of your type, heaped one upon the other, would succeed in slobbering so much as the tips of my august toes?

Marcel stares at him, jumps up, seizes the Baron's silk hat, throws it down, tramples it, picks it up, wrenches off the brim, tears the crown in two.

CHARLUS: What in heaven's name are you doing? Have you gone mad?

Marcel rushes to the door and opens it. Two footmen are standing outside. They move slowly away. Marcel walks quickly past them, followed by Charlus, who bars his way.

CHARLUS: There, there, don't be childish. Come back for a minute. He that loveth well chasteneth well. I have chastened you well because I love you well. He draws Marcel back into the room.

CHARLUS (to footman): Take away the hat and bring me a new one.

MARCEL: I would like to know the name of your informer, sir.

CHARLUS: I have given a promise of secrecy to my informant. I do not intend to betray that promise.

MARCEL: You insult me, sir. I have already sworn to you that I have said nothing.

CHARLUS (thunderously): Are you calling me a liar?

MARCEL: You have been misinformed.

CHARLUS: It is quite possible. Generally speaking, a remark repeated at second hand is rarely true. But true or false, the remark has done its work. Pause.

MARCEL: I had better go.

CHARLUS: I agree. Or, if you feel too tired, I have plenty of beds here.

MARCEL: Thank you. I am not too tired.

CHARLUS: It is true that my affection for you is dead. Nothing can revive it. As Victor Hugo's Boaz said, "I am widowed, alone, and the dark gathers o'er me."

INT. CHARLUS' HOUSE. DRAWING ROOM.

Charlus and Marcel walking through the green room. Music is heard from another floor. A Beethoven romance. Charlus points at two portraits.

CHARLUS: My uncles. The King of Poland and the King of England.

EXT. CHARLUS' HOUSE. THE FRONT DOOR.

The carriage waits. Charlus and Marcel look up at the night sky.

CHARLUS: What a superb moon. I think I shall talk a walk in the Bois.

Marcel does not respond to this.

CHARLUS: It would be pleasant to walk in the Bois under the moon with someone like yourself. For you're charming, really, quite charming. When I met you first I must confess I found you quite insignificant.

He takes Marcel to his carriage. Marcel gets in.

CHARLUS: Remember this. Affection is precious. Do not neglect it. Thank you for coming. Good night.

Unlike Victor Hugo, Pinter's own plays and prose are obscured and difficult, the very opposite of Hugo's pandering. During many moments in The Proust Screenplay, he thrives by keeping the audience in darkness. Pinter uses a honed dramatic convention of setting up a variety of concurrent mysteries and having some of them answer others. The world of Proust, like any drama, is a lot better if you are excited to find out what happens next.

Samuel Beckett was Pinter's guide in this, and all things. He never refuted his mentor, and took every word from the man's lips as the gospel. It was Beckett's inspiration, primarily, to orient the film version around Le Temps retrouvé, the final volume in the book and the one most near and dear to scholars and critics. The adaptation is also structured around the idea of Proust preparing to write In Search of Lost Time, of the experiences that most revolve around the glimmering possibility of becoming the writer he wished to be.

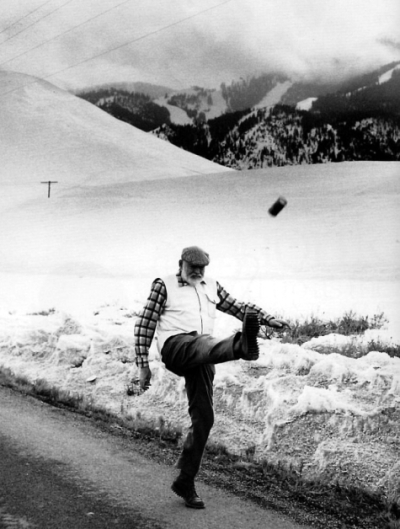

a Japanese production of "The Caretaker"

a Japanese production of "The Caretaker"

It is impossible not to feel some of the doubts Pinter himself felt as a young writer in Marcel's story, and the reflections of his most famous play, Betrayal, in Marcel's scenes with Albertine.

INT. MARCEL'S HOTEL. SITTING ROOM. DAY.

Marcel and Albertine enter the room. He closes the door. She speaks at once.

ALBERTINE: What have you got against me?

Marcel walks to the window, turns from it, sits, looks at her gravely.

MARCEL: Do you really want me to tell you the truth?

ALBERTINE: Yes, I do.

He speaks quietly.

MARCEL: I admire Andrée... greatly. I always have. There you are. That's the truth. You and I can be friends, I hope, but nothing more. Once, I was on the point of falling in love with you, but that time... can't be recaptured. I'm sorry to be so frank. The truth is always unpleasant - for someone. I love Andrée.

ALBERTINE: I see. I don't mind your frankness. I see. But I'd just like to know what I've done.

MARCEL: Done? You haven't done anything. I've just explained it to you.

ALBERTINE: Yes, I have. Or you think I have.

MARCEL: Why can't you listen?

ALBERTINE: Why can't you tell me? Silence.

MARCEL: I've heard reports. She gazes at him.

MARCEL: Reports...about your way of life.

ALBERTINE: My way of life?

MARCEL: I have a profound disgust for women... tainted with that vice. Pause. You see, I have heard that your...accomplice...is Andrée, and since Andrée is the woman I love, you can understand my grief.

Albertine looks at him steadily.

ALBERTINE: Who told you this rubbish?

MARCEL: I can't tell you.

ALBERTINE: Andrée and I both detest that sort of thing. We find it revolting.

MARCEL: You're saying it's not true?

ALBERTINE: If it were true I would tell you. I would be quite honest with you. Why not? But I'm telling you it's absolutely untrue.

MARCEL: Do you swear it?

ALBERTINE: I swear it. She walks to him and sits by him on the sofa. I swear it. She takes his hand. You are silly. She strokes his hand. All those stories about Andrée... She touches his face. You are silly. I'm your Albertine. She strokes his face. Aren't you glad I'm here...sitting next to you?

MARCEL: Yes. She attempts to kiss him. His mouth is shut. She passes her tongue over his lips.

ALBERTINE: Open your mouth. Open your mouth, you great bear. She forces his mouth open, kisses him, forcing him down on the sofa.

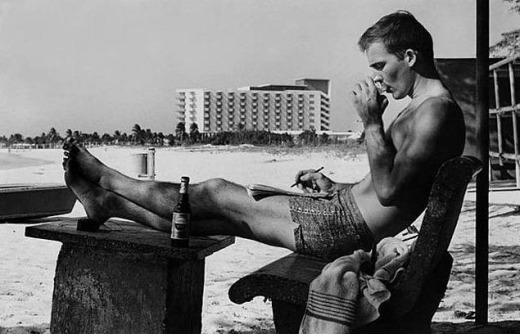

as bassanio in "The Merchant of Venice"

as bassanio in "The Merchant of Venice"

EXT. BEACH. BALBEC. DAY. 1901.

Marcel and Mother sitting in deck chairs.

MOTHER: I think you should know that Albertine's aunt believes you are going to marry Albertine.

MARCEL: Oh?

MOTHER: You're spending a great deal of money on her. They naturally think it would be a very good marriage, from her point of view. Pause.

MARCEL: What do you think of her yourself?

MOTHER: Albertine? Well, it's not that I will be marrying her, is it? I don't think your grandmother would have liked me to influence you. But if she can make you happy...

MARCEL: She bores me. I have no intention of marrying her.

MOTHER: In that case I should see less of her.

performing in a production of his play "The Hothouse"

performing in a production of his play "The Hothouse"

The collaboration between Harold Pinter and Joseph Losey on an adaptation of L.P. Hartley's novel The Go-Between convinced producer Nicole Stéphane the duo were capable of properly distilling source material this voluminous. Before The Go-Between was a hit at the 1970 Cannes Film Festival, Stéphane and her lover Susan Sontag had brainstormed possible directors: at times François Truffaut, René Clément and Luchino Visconti were all attached to the project, with Visconti going so far as to scout locations and commission a rough script modeled on Sodom and Gomorrah.

Pinter was 21 years Losey's junior, and he respected the filmmaker immensely: he never imagined The Proust Screenplay without him. Pinter's two other films with Losey — The Servant and Accident — share a similar haunting tone and perspective on class boundaries, so it was not surprising that he desired a director with whom he shared both kinship and confidence. Ironically, his devotion to Losey was what doomed the project. The once blacklisted director's films never did well in America, and he was considered box office poison.

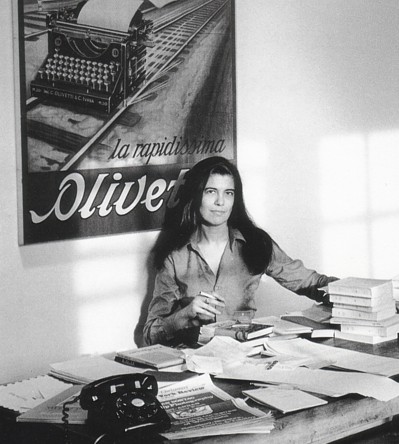

Jacqueline Sassard and Dirk Bogarde in 1967's amazing "Accident"

Jacqueline Sassard and Dirk Bogarde in 1967's amazing "Accident"

Just as Pinter's plays are dark and sometimes frightening, so were Losey's menacing adaptations of his screenwriting. I don't know how they thought these sort of films would appear to a mass audience. Some scenes are heavy with dialogue, others extremely dependent on Losey's masterful editing. In refusing to decide between being stage plays or art films, they used the most exciting conventions of both genres and managed to appeal to neither audience.

In The Proust Screenplay Pinter is more accessible than in any of his stage works, taking a familiar story and never shying from a crowd-pleasing line or innuendo. It is his broadest masterpiece.

When biographer Michael Billington asked Pinter why another director was never approached, he said, "Nobody ever suggested that to me. It would have been quite pointless to say that to me. They may have suggested it to Barbara. Nobody did to me because I wouldn't have given it house-room." He values loyalty in a way Marcel does not.

Pinter with Liv Ullman in a revival of his "Old Times"

Pinter with Liv Ullman in a revival of his "Old Times"

EXT. PARK AT TANSONVILLE. DAY. 1915.

The pond, seen through a gap in the hedge.

A fishing line rests by the side of the pond, the float bobbing in the water.

Marcel and Gilberte appear and walk to the side of the pond. They are both aged thirty-five and both dressed in mourning.

GILBERTE: Two days after Robert was killed I received a package sent anonymously. It contained his Croix de Guerre. There was no note of explanation, nothing. The package was posted in Paris. Pause. Isn't that strange?

MARCEL: Yes.

GILBERTE: He never mentioned, in any letter, that it had been lost, or stolen.

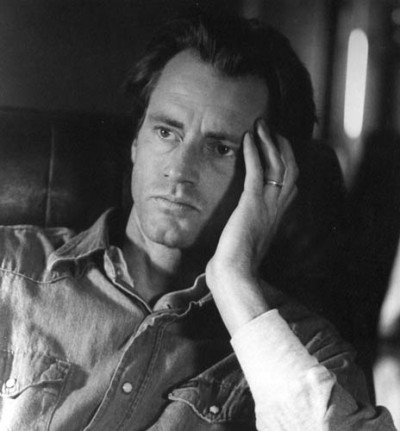

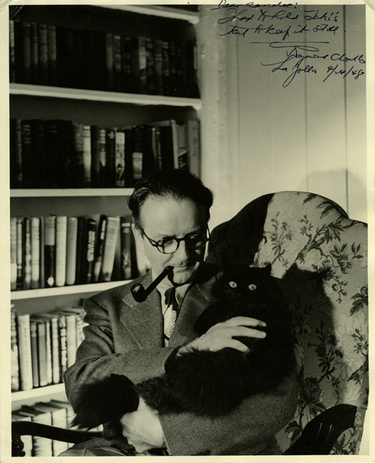

in his acting days, after a performance of Lady Windermere's Fan

in his acting days, after a performance of Lady Windermere's Fan

INT. DRAWING ROOM. SWANN'S HOUSE AT TANSONVILLE EVENING.

Marcel and Gilberte stand by the windows.

GILBERTE: I loved him. But we had grown unhappy. He had another woman, or other women, I don't know.

MARCEL: Other women?

GILBERTE: Yes. He had some secret life, which he never confessed to me, but I know he found it irresistible.

with Julie Christie on the set of "The Go-Between"

with Julie Christie on the set of "The Go-Between"

EXT. PARK. TANSONVILLE. MORNING.

Marcel and Gilberte walking.

GILBERTE: Do you remember your childhood at Combray?

MARCEL: Not really.

GILBERTE: How long is it since you've been back?

MARCEL: Oh, a very long time. It's changed.

GILBERTE: The war has changed everything.

MARCEL: No, it's nothing to do with the war.

GILBERTE: But are you saying that these paths, these woods, the village, excite nothing in you?

MARCEL: Nothing. They mean nothing to me. It's all dead. I remember almost nothing of it. Pause. I remember seeing you, through the hedge. I adored you.

GILBERTE: Did you? I wish you'd told me at the time. I thought you were delicious.

Marcel stares at her.

MARCEL: What?

GILBERTE: I longed for you. Of course I was quite precocious, I suppose, then. I used to go some ruins - at Roussainville - with some girls and boys, from the village, in the dark. We were quite wicked. I longed for you to come there. I remember, that moment through the hedge, I tried to let you know how much I wanted you, but I don't think you understood. He laughs.

GILBERTE: Why are you laughing?

MARCEL: Because I didn't understand. I've understood very little. I've been too... preoccupied... with other matters... To be honest, I have wasted my life.

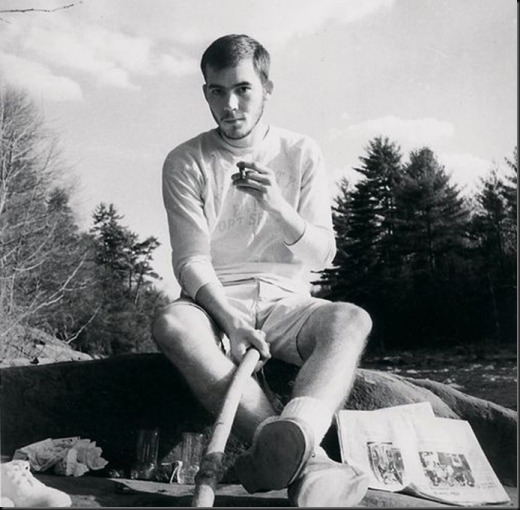

with Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal

with Nicaraguan poet Ernesto Cardenal

Pinter largely ignores the portrayal of Jews in In Search of Lost Time. Marcel hears gossiping about the Dreyfus affair but that it is all — his Jewish friends and acquaintances have vanished like Marcel's familiar madeleine cookie. Pinter's people were a band of North London Jews; Pinter's paternal grandfather fled from a Russian pogrom. Passover was a big event in his house as a child, but like many European Jews, he rejected the religious dogmatism of his parents. He was concerned with "world affairs" and considered himself a man of Earth.

Proust is not concerned with morality, but like all self-righteous atheists, Pinter is obsessed with it. Primacy to his own experience was Marcel's ideal, Pinter's is primacy to his own moral code. In every scene of The Proust Screenplay, he casts his own judgment over the proceedings. The challenge to Losey is huge. Although he lists shots, so much is left off, can only be hinted at:

Pinter's adaptation of Proust requires another creative mind to infiltrate his own, and find the perspective justified, confirm his suspicions about the characters and events. Because The Proust Screenplay is only a script, we are given this interpretive task as readers. Even in the work's harshest and most mind-rending moments, it is the thrall of being correct and therefore superior, the rationalization following our primal emotions, that lies closer to Harold's heart. He is watching these people and telling us how to live with what they said and did. He writes,

Proust wrote Swann's Way first and Time Regained, the last volume, second. He then wrote the rest. The relationship between the first volume and the last seemed to us the crucial one. The whole book is, as it were, contained in the last volume. When Marcel in Time Regained says that he is now able to start his work, he has already written it. We have just read it. Somehow the remarkable conception had to be found again in another form. We knew we could in no sense rival the work. But could we be true to it?

Every adaptation is a moral act; imagine Proust trying to do to In Search of Lost Time what Pinter did to it. He would never, and he would wonder why it needed to be done.

with joseph losey and james fox (left)

with joseph losey and james fox (left)

In 1930, Samuel Beckett related his view of Proust in his bizarre and brilliant monograph on the author, a piece hellbent on serving its author more than its ostensible subject. (Beckett was perhaps overly critical of his younger self when he later wrote, "I have written my book in cheap flashy philosophical jargon.") It was Beckett's mature view of À la recherche du temps perdu that informed every step of Pinter's process.

There is no more exciting interaction of two European masters except possibly in Freud and Jung. Beckett's view is necessarily bleaker — it is the contrast between the two similar styles that keeps Pinter's work hopeful enough to survive in the theater. For in Pinter's drama, joy never comes easy.

The cinematic image, then, becomes home to the explosive feelings he can't handle through speech. Proust's constant exposition and narrative meandering is anathema to a playwright; instead of representing them literally, as he is loathe to do, Pinter places them in the stage directions for Losey to visualize. (Ever watched a director during his own screening?) Later, he plans to silently and morbidly screen the final product with the director he called Joe, obsessing in the same fashion others view old photos of lost friends. Because The Proust Screenplay never received the elaborate production it deserves before his death, Pinter was denied the feeling — disconsolate or euphoric — of witnessing himself.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He tumbls here and twitters here. He last wrote in these pages about Jim Henson and Sesame Street.

"Children" - The Rapture (mp3)

"Roller Coaster" - The Rapture (mp3)

"In The Grace Of Your Love" - The Rapture (mp3)

The new album from The Rapture In The Grace Of Your Love comes out on September 6th.