FILM

FILM In Which Anjelica Huston Falls Off The Horse Again

Thursday, January 5, 2012 at 10:49AM

Thursday, January 5, 2012 at 10:49AM

Angel of Import

by ELLEN COPPERFIELD

That's the great self-indulgence, isn't it? To do what interests you?

- Katharine Hepburn on the director John Huston

Anjelica Huston was born in the absence of her father. Weeks earlier, shortly after John Huston began shooting The African Queen in the Congo, he killed his first elephant. A week previous to that, the married director (not to Anjelica's mother, naturally) had made a pass at the film's 22-year old script coordinator. She cried. Lauren Bacall noted, "He was a little frightening to watch."

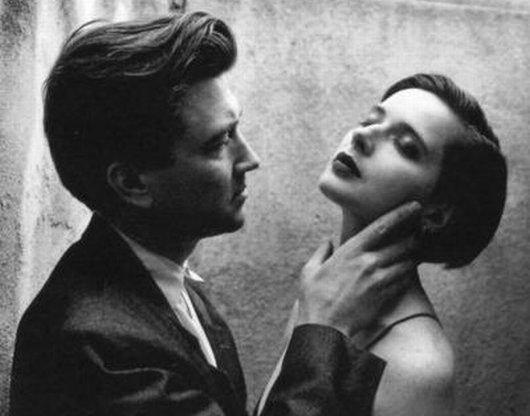

Anjelica's mother Ricki Soma eventually became John's fourth wife. As an eighteen year old ballerina she had been on the cover of Life magazine:

Until he divorced his third wife, Evelyn Keyes, Ricki officially occupied the position of John Huston's mistress. Still, they lived together in Malibu. Ricki's first pregnancy was something of a surprise, but by the seventh month, John was divorced and they were married. The boy was named Walter Anthony after John's father, and they called him Tony, after Ricki's.

John was soon cheating again, this time with a woman who was essentially Ricki Huston's double, Suzanne Flon. To his surprise, he fell in love with her. (One of John's exes once called him "an angel with a gun in his pocket.") Proceeds from his next picture, the popular 1953 jaunt Moulin Rouge, allowed Huston to resume a more lavish lifestyle. He rented a house in Ireland and moved Ricki there. John drove very fast everywhere he went.

St. Clerans

St. Clerans

In Ireland Huston's son Tony almost died in a horse accident, and Anjelica lost part of her finger in a lawn mower. She also fell over their dog Rosie and badly bruised her hip. Another time, she put her arm in a clothes wringer and could barely extract herself from the device. In time, Ricki would move with the kids to Italy. But instead of then divorcing her philandering husband, she found a house in Galway, Ireland, and the family stayed together.

John's next project was a collaboration about the life of Freud with Jean-Paul Sartre. The two giants hated each other immediately. John said of Sartre, "One eye going in one direction, and the eye itself wasn't very beautiful, like an omelet. And he had a pitted face." Sartre was constantly writing down things he himself said in conversation, and he never stopped talking. The lack of respect was mutual. Sartre wrote to Simone de Beauvoir, "Through this immensity of identical rooms, a great Romantic, melancholic and lonely, aimlessly roams. Our friend Huston is absent, aged, and literally unable to speak to his guests... his emptiness is purer than death."

Anjelica lived in her own little world, only associating with the children of the household's groom. Little of their parents' angst reached the kids. Anjelica would later tell biographer Lawrence Grobel, "They were sort of two stars in the heavens when I was growing up." Anjelica wanted to become a nun, because they were the only other women she associated with on a regular basis. When she told her father of her intentions, he said, "That's great, when are you going to start?"

Her parents kept their secrets close to the vest. For a long time she did not know her father had impregnated another woman, a young Indian actress named Zoe Sallis. When John finally decided to rid himself of Ricki, they barely informed the kids. Anjelica later said, "We were just told, 'You have to go to school in London now. And your mother will live in London with you, and you'll come back to Ireland for holidays.'" She was put into the Lycée Français, where she was expected to learn in French. For tax reasons, Ricki would not grant him a divorce. John kept Ricki in London and Zoe in Rome.

John, Danny and Zoe Sallis

John, Danny and Zoe Sallis

Once, at a family meal, the discussion revolved around Van Gogh. "I said somewhat flippantly that I didn't like Van Gogh," Anjelica recalled in Lawrence Grobel's 1989 portrait of the family, The Hustons. He said, 'You don't like Van Gogh? Then name six of his paintings and tell me why you don't like Van Gogh.' I couldn't, of course. And he said, 'Leave the room, and until you know what you're talking about, don't come back with your opinions to the dinner table.'"

They still visited Ireland in the summer. The girls would sit in the barn's hay loft, watching the horses have sex. A stallion would take on mare after mare. Anjelica's friend Joan Buck noted, "Anjelica and I thought this was the way it went."

Anjelica with Joan Buck, Christmas 1959

Anjelica with Joan Buck, Christmas 1959

Anjelica hated taking the London underground to school. She wished her mother had more money so she could come to school in a limo like the other girls. Her father was increasingly absent, and her mother became pregnant by an English writer/aristocrat with a family of his own. She did not tell Anjelica she was with child until the baby's birth was three months away. (Anjelica recalled, "I thought she was putting on weight.") A week later, John Huston told her for the first time about her half-brother Danny, now two years old.

Anjelica's emotions were sky high one minute, pathetically low the next. While she was away in Ireland, her poodle Mindy died. John Huston goaded a visiting John Steinbeck into playing Santa Claus for the kids. Steinbeck's wife almost stroked out.

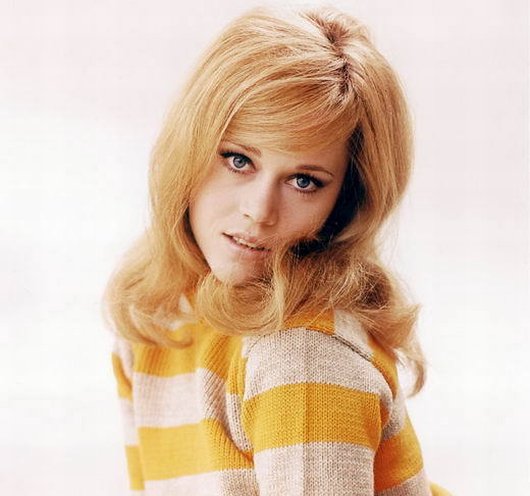

By the age of fifteen, Anjelica was the second-tallest girl in her class. Suddenly, John's little girl had become a woman, and in makeup and adult clothing, she was more than a simple beauty. Her mother encouraged adoption of the latest fashions, wanting to relive her own youth in her children. Ricki's friend Dirk Bogarde would remark, "There seemed to be no age difference at all."

They parted ways on the issue of drugs. Ricki desperately wanted to keep Anjelica away from London's scene. When a producer on John's new project wanted Anjelica for a role (it would have kept costs down), her mother strenously objected to that as well. Anjelica wanted to play Juliet in Franco Zeffirelli's version of Shakespeare's play, and had been encouraged by several callbacks. Her father made the decision for her.

"A Walk with Love and Death"

"A Walk with Love and Death"

When she showed up on set of A Walk with Love and Death, John was incensed to see she had cut her hair. (Extensions were required and took hours to insert properly.) Father and daughter did not get along on set. She later told Grobel, "The fact that I was ungrateful and petulant about it was hardly something he could have expected. Katharine Hepburn didn't criticize his direction? Why should I?"

Her next gig was as understudy to Marianne Faithful in Tony Richard's stage version of Hamlet. It helped shape her into a somewhat decent performer. Although news that a topless photograph might appear in an Italian magazine horrified Ricki, she went to great lengths to get her daughter her first spread in Vogue. The following January, Ricki's car hit an Italian pothole and her boyfriend swerved into the path of an incoming van. Anjelica's only mother was instantly killed.

Bogarde said, "Ricki was dead. I'd never see those humorous eyes, the sadness beneath them almost concealed; I'd never see the idiotic daisy-chains, hear the laughter, discuss the latest book, play, ballet or opera; never see her come in from a walk, muddy, wet, with the dogs. Life would go on, but never quite in the same way ever again." John Huston was not in great shape either. Even though he had difficulty breathing, he still smoked four cigars a day. (He tried pot once years before and had to be hospitalized.)

Her mother's death pushed Anjelica deeper into modeling. A relationship with photographer Bob Richardson was a tonic of sorts; he kept her extremely thin and yelled at her constantly.

Richard Avedon had told Ricki he thought Anjelica's shoulders were too big. Despite that, her unique look found work. "I had a big nose," she later said. "I was still growing into my body. The idea of beauty for me was Jean Shrimpton — big blue eyes and little noses, wide bee-stung mouths. It was an odd dichotomy — and this happens to many girls who find themselves in front of the camera a lot, who truly don't like their looks. It's almost as thought they can forget their looks in front of the camera. And I used to love working for the camera. But when faced with the reality of my pictures, I was generally deeply depressed." New York became her adopted home.

When her father remarried again, Anjelica was not even invited. When her relationship with Richardson flamed out, she began staying in the Palisades with John and his new wife, Cici. In time she moved into a house on Beachwood Drive. It was Cici Huston who would introduce her to Jack Nicholson. She was just 22, he was 36. They began dating straight away, in an on-and-off relationship that would consume sixteen years of her life.

It was March of 1977 when Anjelica headed to Jack's house to pick up some clothes. She intended to take them back to the apartment of her new boyfriend, Ryan O'Neal. Instead of Jack or an empty house, she found Roman Polanski and a thirteen year old girl named Sandra. When the police came back to the house with Polanski to search, they found both Anjelica and the cocaine in her purse. In order to protect herself from prosecution, she agreed to testify against Polanski. Without her testimony, it was doubtful there would ever be a conviction. She agreed, and the director fled.

Things with O'Neal were no better than they had been with Jack. He frequently exploded at Anjelica's half-sister Allegra, who John cared for as his own. Allegra still did not know who her real father was, and it was John's new wife Cici who finally forced the issue, informing the girl herself. In time, Anjelica returned to Nicholson. She came along when he travelled to England to shoot The Shining with Stanley Kubrick. They broke up for good in 1989.

In 1980 she was involved in a car accident which would alter the rest of her life. She was hit by a drunk 16 year old driving a BMW. She was not wearing a seatbelt and her face was decimated. She immediately directed the attending ambulance to Cedars-Sinai, sensing she would need extensive plastic surgery. When she left the hospital, her nose was actually looking somewhat better. She changed her life, moving out of Jack's house and living alone for the first time.

Ellen Copperfield is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in San Francisco. She last wrote in these pages about the childhood of Simone de Beauvoir. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

Relive Your Childhood One Blog Post At A Time

Ellen Copperfield and the younger daze of

"Animal (Fred Falke remix)" - Miike Snow (mp3)

"Animal (Mark Ronson remix)" - Miike Snow (mp3)

"Silvia (Sinden remix)" - Miike Snow (mp3)