THE WORLD

THE WORLD In Which We Contemplate Our Daemons

Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 10:11AM

Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 10:11AM

The Spirit Animal

by KARA VANDERBIJL

At the shelter, they recommend that you sit on the floor and wait for the right animal to approach you. Ideally, you will connect with an animal that best fits your needs, based on any number of inexplicable factors that draw a cautious prowler to the hollow of your lap.

If you have a 9-5, it will be fine home alone during the day. If you like to have loud company, it won’t have to hide under the bed. If you don’t have money, it will never require medical attention. If you are insecure, it won’t look at other humans. This highly anticipated encounter, like going unescorted on a Friday night to any local watering hole, is a game of pheromones that eludes the human subject and thus makes it ridiculous.

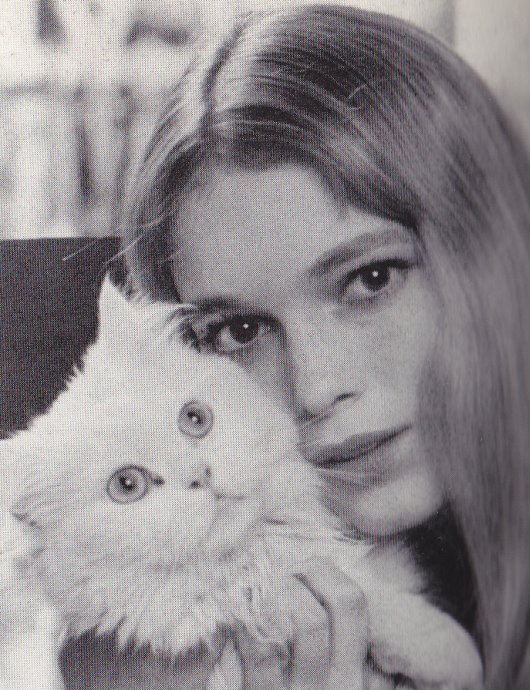

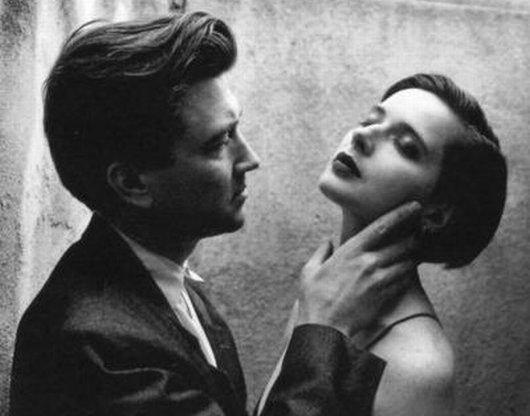

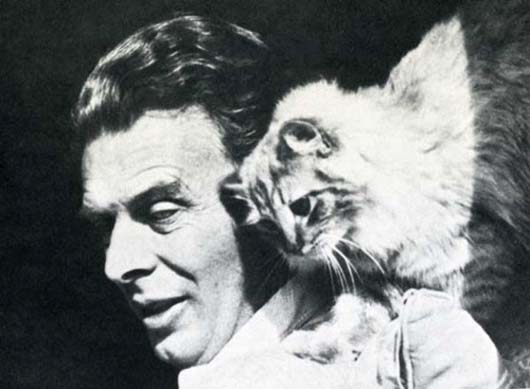

neil gaiman by kelli bickman in 1996

neil gaiman by kelli bickman in 1996

Any understanding between man and animal (as with man and man) is nothing but a profound misunderstanding. When claws or fangs draw blood, we expect a beast’s empathy, if not its complete understanding that it deserves death and punishment. Why then, in the subtle lairs of our living rooms, do we endow upon the creature our wildest animal instincts? How can we laugh at the proclivity to chase sunbeams across a wood floor?

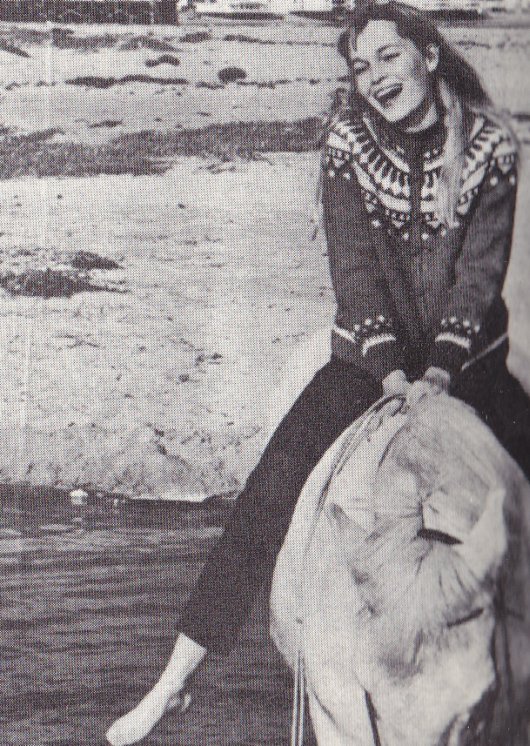

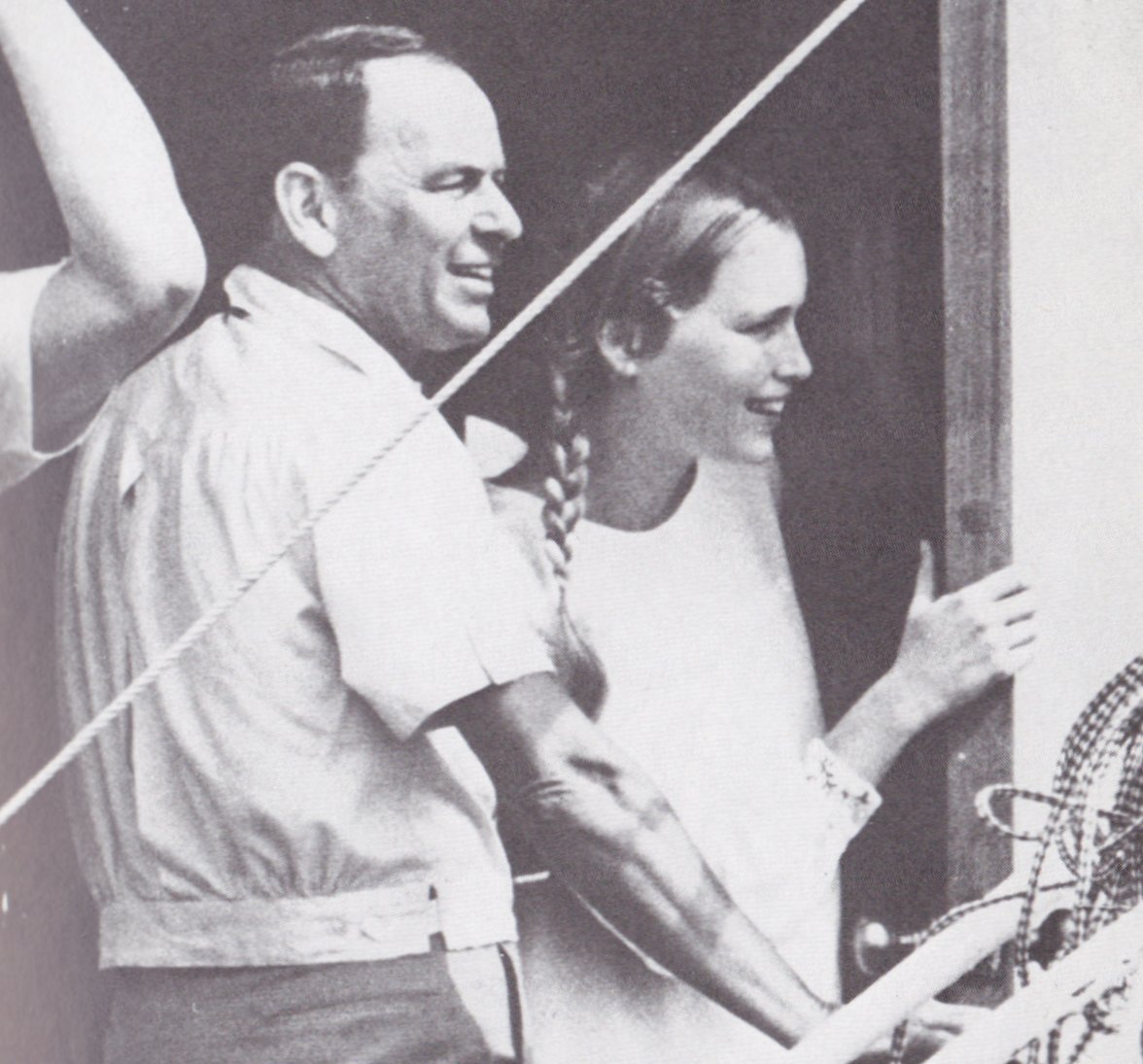

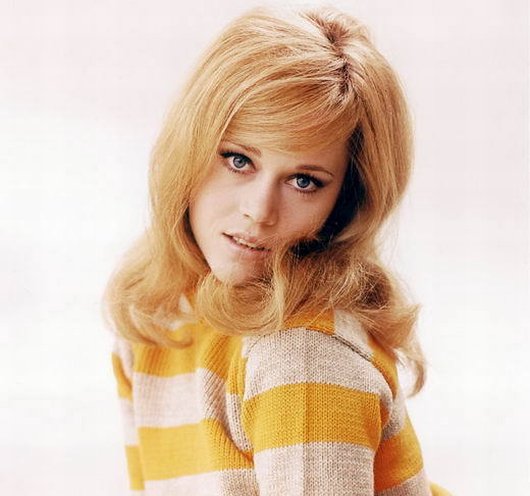

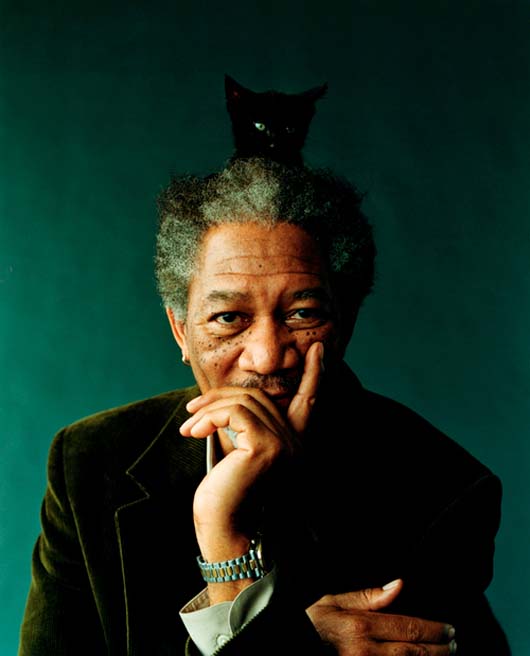

elizabeth taylor

elizabeth taylor

The natural state of any living thing, except a Happy Meal, is birth and death. What happens in between those two is the great debate. Before the spirit animal, men and women were driven to hide their essences elsewhere: gaudy containers, pieces of jewelry, bottles rolled away to the safety of the sea. Like what people did before blogging, it is something we may never know for sure. There was nowhere to hide in plain sight.

Of the first cat I remember, auspiciously named Plato, we saw only snatches of dark fur, a paw flung carelessly over the edge of an armchair. When unprovoked, he remained indifferent, although ornery for such a handsome and well-fed specimen. Provoked (easily), he appeared twice his usual size, producing unearthly growls that eventually got him banished to a curtained back bedroom. On one occasion he stalked angrily around the coffee table while my brother and I trembled on all fours behind the sofa. He suddenly appeared in front of us only to leap, claws extended, and we screamed. Only his mistress, my aunt, and sometimes my uncle, could coax him into their arms – a privilege no doubt acquired by the blood sacrifice of many small and unfortunate creatures. Left to his own devices, we felt sure that he would murder us in cold blood.

Did philosophy or religion exist without this animal? At the incline of its head nations tumbled, empires fell to dust. Nepalese peaks rose in imitation of its clever ears. At the very least, corners proved darker for its playful ambush of passing feet, windows larger to frame its wise face. The arts owe more to the feline than to any other creature, save perhaps the horse. Somewhere in the desert, an ancient Sphinx rests on time and mankind’s imperfect worship.

Unlike its feral counterparts, the housecat is a follower of Epicurus, its basest passions restrained by a constant striving after pleasure. Survival is less important than aesthetics, a subject explored by the animal in great detail as it reclines fluidly on the rug. Its ennui humanizes it, as it progressively forgets (intentionally, unintentionally) why it was placed on earth.

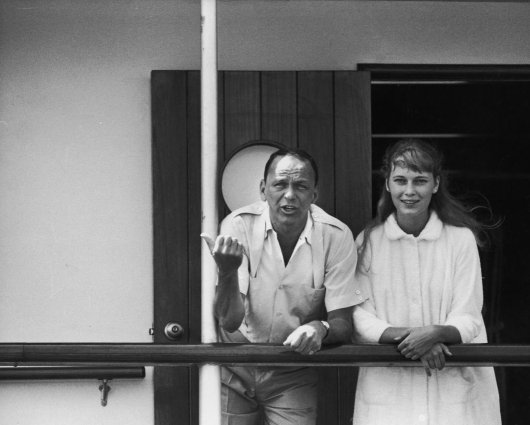

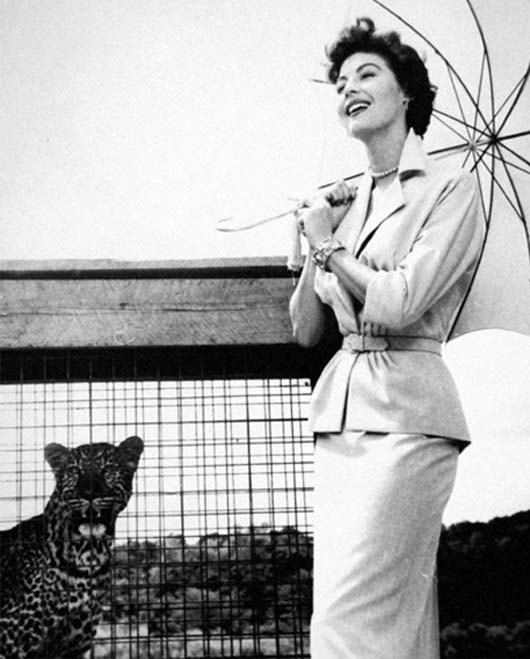

grace kelly

grace kelly

We inherited our first family cat in California, when my parents managed an apartment building. An elderly tenant moved or passed away, and according to standard apartment procedure the managers ended up with whatever was left beneath sinks or in the back of the closet.

Mikey was an ancient orange and white tabby and I think we saw him a grand total of five times while we were in his possession. He spent most of his time wedged underneath my parents’ bed, although we made sure he was still alive by shaking his box of dry food and calling his name, a clever ruse that got him to frolic like a kitten down the hallway. In the mornings he mewled outside shut bedroom doors, awake only when nobody else was. Shortly thereafter we moved, and another tenant took him. In all likelihood he still lives in the San Fernando Valley surrounded by Koreans.

The survival of a species depends entirely on the ability of its hunters, on the secrecy of its cache. Infamous tiger-slaughterer Jim Corbett shared pleasantries with many a man-eating feline at dusk over bait. If they lunged, he fired his gun. An otherwise grandfatherly-looking man, he mostly hunted alone with his small dog Robin. In tales about the Chowgarh tigress it is unclear whether he was hunting or wooing her. Concrete slabs mark the spots in India and Nepal where he finished them; we can imagine him tenderly composing pet epitaphs at night to the howl of nearby monkeys. He devoted his later years to the preservation of endangered species, no doubt fearful of karma.

Dad kept a freshwater aquarium for a few years, and Mom indulged in parakeets and a couple of yellow canaries. My parents provided us with a cat every few years, despite their general reserve towards the animal kingdom. It showed a remarkable ability on their part to see our potential for compassion. Still they were the first to pick up the slack when it proved once again (as it always did) that we were still very young, and that we could not yet grasp how another living thing might need us. They allowed disquiet at the foot of their bed and shoveled through litter boxes and patiently satisfied another hungry stomach.

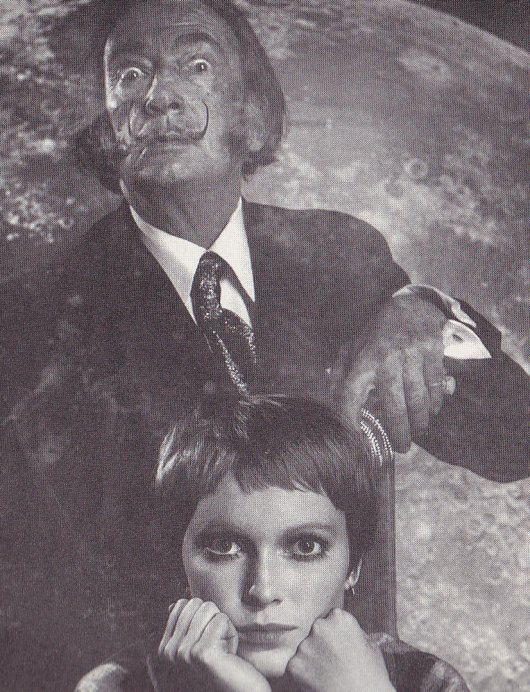

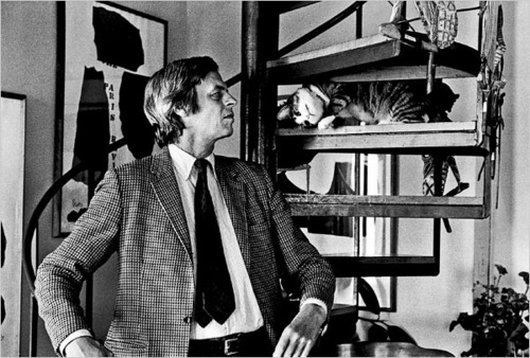

aldous huxley

aldous huxley

To identify with or as is the siren song of this generation, an ongoing game of association in which the subject pinpoints behaviors, fashions, morals, or ideologies and appropriates them to himself. (e.g. I must be Liz Lemon because I think and act and speak like Liz Lemon. Ryan Gosling must be my boyfriend because Ryan Gosling speaks and looks and thinks and acts like I want my boyfriend to act.) The spirit, it would seem, has become as much of a consumer as the body. This is vanity.

For a long time the most desirable relationship was such a one as existed between Calvin and his stuffed tiger Hobbes, or between Lucy and Aslan, a bond in which similitude transcends any differences of kind or quality. In any case, this relationship seemed highly preferable to any story in which animals only talk amongst themselves, which is believable only inasmuch as reality television is believable.

In the early 00s, my parents somehow became acquainted with farmers in the Haute Savoie, a portion of France irreversibly wrinkled by that majestic mountain range known as the Alps. From them we received goat’s cheese, lessons in vocabulary, and a chaton – a tiny ball of brown and white fur we unorginally named Simba. We brought him home in a cardboard box. He peed on a towel. From the very beginning, we strove to teach him the difference between right and wrong using a squirt gun. He chased our ankles and climbed papered walls. When he took to running in wild circles around the apartment day and night and howling at the moon, we released him in a meadow near a friendly-looking barn and stacks of warm, plush hay. He did not look back.

Otherwise, it was our constant hopping from one location to another that prohibited a long-term relationship with a pet. It was also our own inability to remain constant, our chameleonesque capability to blend into language and space, adopting the same awkward ease with which an academic handles reality: drawing on a vast well of knowledge, but with very little practice.

Domesticating an animal, like educating a child, rationalizes its wilderness of instincts, robs it of the power quivering on its whiskers. An oblong box filled with sand might just as well be a place to shit as a place to rest in peace. If eternity is man’s natural habitat, he cannot be blamed for chasing it by dividing his soul into parts.

Kara VanderBijl is the senior editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about Jeffrey Eugenides‘ The Marriage Plot.

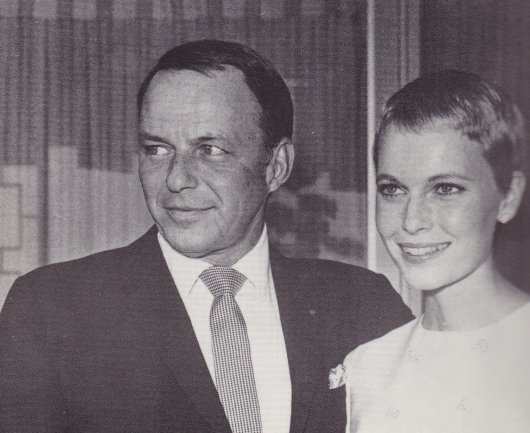

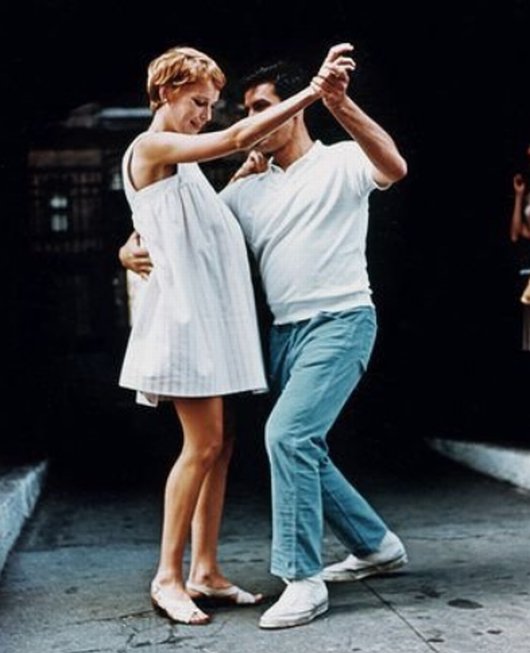

ava gardner

ava gardner

"Lúppulagið" - Sigur Ros (mp3)

"Popplagið" - Sigur Ros (mp3)

"Flijotavik" - Sigur Ros (mp3)

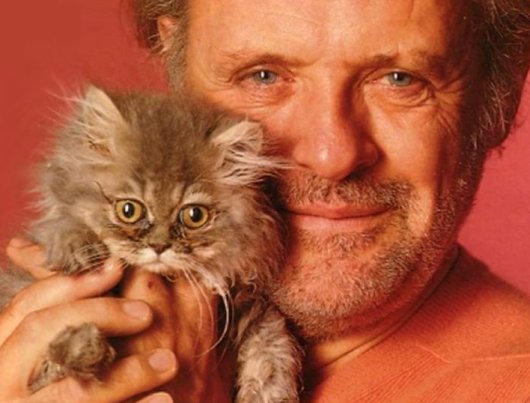

george plimpton

george plimpton