Pictures of My Father

by TYLER COATES

The first real memory I have of my father is, like most of my "first memories," actually something that was captured on video when I was about three years old. My father came home on his lunch break, and he walked into the house to find me screaming at my grandmother. Instead of calming me down or telling me to shut up, he instead took the opportunity to capture the moment on home video. So somewhere in my parents' house there's a VHS tape with clips of me stomping around my living room and screaming, "Day-day," which was what I called him until I was about five years old. I think that perfectly introduces the relationship I had with my dad. I always joked that my mother was The Boss. At a very young age I understood that she was the breadwinner; she worked for the Navy as a computer scientist, whereas my father was dispatched around my rural Virginia area from the local Coca-Cola bottling plant fixing drink machines and fountain units.

Northern Neck Bottling Company, Montross, Virginia

There was never a strong conflict between my parents because of their uneven salaries. I didn't know how much they made until they co-signed on my first apartment out of college. When I say that my mother was The Boss, I mean it in the sense that she was the disciplinarian. She had a temper and very little patience for misbehavior, while my father, on the other hand, sometimes encouraged it.

Fleetwood Farm, Acorn, Virginia

My dad was born in Acorn, Virginia, which is a town only in the sense that there is a sign on the side of the road that reads "Acorn." He was born at home, in the house that my grandmother still lives in. He was the second of three children, and he lived at home from his birth in 1950 to the year he married my mother in 1976.

My father, my uncle Andy, my grandfather, and my aunt Lynn on the Minneapolis-Moline.

My grandparents were poor, which is a knowledge I grew up with. My father didn't tell stories about how he walked five miles to school in the snow (he only did it once - he missed the school bus and my grandfather refused to give him a ride). They didn't have indoor plumbing until my father was seven.

My great-grandfather, my father, my uncle Andy

Instead of complaining about his family's poverty, he described it in the way he did about everything: with a self-deprecating joke. "When I grew up the only toys I had were a spoon and a piece of asbestos."

There are very few pictures of my dad as a child because my grandparents could not afford a camera. The majority of the pictures we have of him as a kid are school pictures, or, in the special case below, a photograph of his visit with Santa Claus in Richmond.

My father went to the same high school as my mother (which is the same school both my brother and I attended over twenty five years later), but they were not high school sweethearts. They ran in different circles (if that is possible when your high school has about two hundred students). He was in the FFA, a football player (because, as he told me, "They let everyone who tried out on the team."), and in two bands.

The Rambling Rebels (larger image and full caption here)

It should be noted that my father could be described as a Good Ol' Boy - he was raised in the South and matured during the '60s. While he missed the major action of the Civil Rights Movement (his was the last graduating class of the segregated public high school in 1970), he was certainly affected by it, as were most of his generation. My mother once admitted to me that people her age in the '60s sported Confederate insignia and repeated the line, "The South will rise again," but, in her words, "We didn't really know what that meant." At the same time, my father loved the music of the black artists that recorded with Motown and Atlantic. He saw Aretha Franklin and the Jackson Five in concert, and even when I was a kid, I remember the sounds of Otis Redding, Sam and Dave, and Wilson Pickett playing on the car stereo. So, while he was in a band called The Rambling Rebels and pasted the Confederate flag on his drum set, he sang in another band in 1968 called The Soul Creations.

The Soul Creations - my father is the second from left. I'm sure they sounded a lot like Spoon.

My parents went on their first date just after Christmas in 1972; my mother was a freshman in college and home for break. My father, who was four years older but one year ahead of her in school (he had been kept back two grades, she skipped one), was working his first job out of high school digging septic systems.

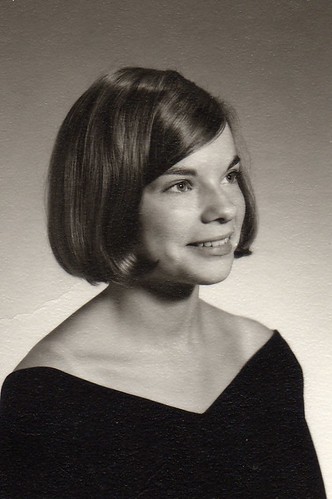

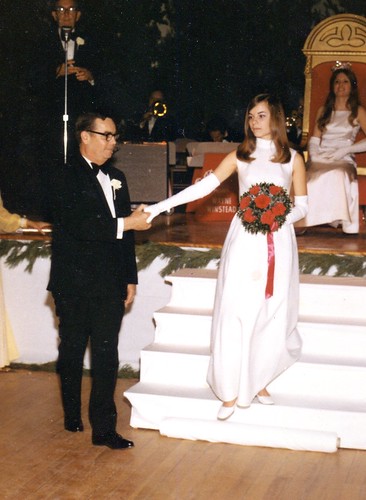

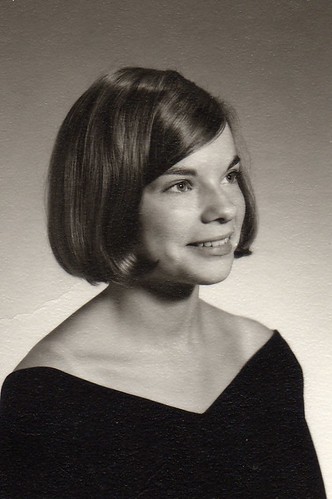

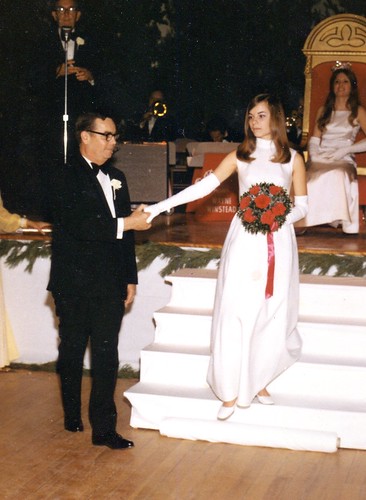

My parents always seemed like completely opposite people to me. My father grew up poor, my mother upper-middle-class. My paternal grandparents were uneducated farmers; my mother's father was a lawyer who graduated from the law school at the College of William and Mary (he was a member of a group students who saved the law school from closure - the state originally wanted to have one supported law school at UVA), her mother a retired schoolteacher and housewife. Both of my maternal grandparents could trace their lineage to the First Families of Virginia. My mother, of course, was a debutante.

After four years of dating, my parents married in June 1976 and settled in the area where they - and their parents - grew up.

When speaking of the day he married my mother, my father always said it was the second happiest day of his life, the first being the day his father sold the pigs. His third happiest day was the day my (younger) brother was born in 1989; the fourth being my birthday in 1983.

I have to find some truth in the idea that your life flashes before your eyes before you die. After all, your life flashes before your eyes all of the time: memories come in and out of your head in a fluid motion.

Like dreams, they don't often follow a logical pattern, nor do they always represent what actually happened in the past. When I think of my childhood, things are hazy in the sense that I'm not entirely certain I'm remembering what actually happened to me, or if I've just seen those things in pictures for over twenty years.

I have the same feeling when I remember my father, who died in May of this year from pancreatic cancer. I look at pictures of him and think, "Yes, that is what he looked like." But away from photo albums, I don't see him at 38, when I was five years old. I can look at a picture of him in high school, or in 1978 and think, "That is my father, and that is how I knew him."

But during the day, away from the scanned images of those old photos, the picture in my head is from three months ago: my father is 57, and he is laying in a hospital bed in my parents' room. For the first time in his life he does not look young for his age; he is old, tired, and his wrinkled skin is loose on his face because he hasn't eaten in two weeks. There are, luckily, no pictures of my father from the last two months of his life.

My father and me, Christmas 2006

My father was diagnosed with cancer in February 2007. With most cases of pancreatic cancer, the diagnosis comes months, even weeks, before the patient dies. My father, on the other hand, was extremely lucky; his cancer was still in early stages, and his doctor was very confident that with a combination of chemotherapy and radiation, my father's life could be extended immensely compared to other patients. He did, however, specify to my parents that the number of patients who lived for five years without the cancer returning was very low. My father, forever the optimist, replied, "So, we do have a chance!"

August 2007

My father had an amazing personality. I can't count the number of people who told me that he had never met a stranger, simply because he somehow managed to get along with nearly anyone. I credit his small-town upbringing; at the same time, he grew up with a notoriously unaffectionate father, which made my father completely opposite. My father would demand a hug and a kiss from my brother and me when we were fifteen, in public no less.

November 2007

My father responded well to his chemo and radiation therapy, and by the end of November 2007 he was in remission. At the same time, however, he tried to hide that he knew that his days were numbered. In August, as we crossed the bridge from the Outer Banks of North Carolina (where my parents have vacationed every year since the early years of their marriage) to the mainland, he cried and told my mother that it was the last time he'd be there. After Christmas he unsuccessfully attempted to conceal his illness from my mother, which is difficult when you're trying to hide feelings from a person you've known and spent nearly every day with for thirty-five years.

Dad went through a second round of radiation and chemo, which left him withered and tired. By the time he went into hospice care in May of this year, he had lost about 90 pounds. I flew home from Chicago for what was originally supposed to be a weekend visit, but I spent three weeks at home. I came home in time for his last few days of being aware of his surroundings, floating in and out of a morphine-induced haze. He held on for a week and a half, which my family spent holding a vigil of sorts. There'd be hours were we sat around the rented hospital bed, crying and holding his hand, hoping for a quick release from the pain that my father's illness was causing all of us to experience. Other times, we'd be down the hall in the living room, slamming down multiple glasses of red wine, which, like the casseroles and flowers delivered by the neighbors, were brought into the house in bulk shipments.

We prepared for my father to die, but in a way that surprisingly felt like a party rather than a somber occasion. We told stories about him and shared the memories we had. My mother and my father's sister argued over events that took place in those stories, I listened to the familiar tales that had changed and evolved over the years. It sounds like a cliche, of course, but it's true to my father's sensibility. He was a storyteller, a joker. He always had some elaborate tale to tell, and he never told the same thing twice - which, of course, was unintentional. He was plagued with a bad memory, and he couldn't help but tell the same story over and over, but it changed each time. Fittingly, the preacher who delivered his eulogy somehow managed to mix up the stories that my mother and I provided as research. He placed me and my brother into a story of a trip to Washington, DC in the late '70s, for example.

We prepared for my father to die, but in a way that surprisingly felt like a party rather than a somber occasion. We told stories about him and shared the memories we had. My mother and my father's sister argued over events that took place in those stories, I listened to the familiar tales that had changed and evolved over the years. It sounds like a cliche, of course, but it's true to my father's sensibility. He was a storyteller, a joker. He always had some elaborate tale to tell, and he never told the same thing twice - which, of course, was unintentional. He was plagued with a bad memory, and he couldn't help but tell the same story over and over, but it changed each time. Fittingly, the preacher who delivered his eulogy somehow managed to mix up the stories that my mother and I provided as research. He placed me and my brother into a story of a trip to Washington, DC in the late '70s, for example.

Growing up, I knew a lot of kids whose parents were divorced - so many, in fact, that I felt left out that mine were still together. I only knew one girl who had a parent die when she was a young age. I felt both normal (in the sense that losing a parent as a child was something that only happened in movies) and out of place (because I only had two parents, not four). Growing up, I realized that my parents had a nearly perfect marriage, despite their opposite upbringings and childhoods. I can't imagine what it is like to be married to someone for almost 32 years (and being with that person for almost 36) and suddenly lose them.

My father left a lot behind when he died. For my brother and me, there is the enormous cache of stories and memories, both from our lifetimes and previous. I have pictures of him - a few from his childhood, even more from my parents' life together before I was born, and a ton since then. My mother, on the other hand, has two sons who look a lot like their father. She has the house they built together when they married. And she has my father's final gift, which is the last metal Coca-Cola sign he built and painted for the owners of Driftwood, which was my parents' favorite restaurant.

My father's name, which he printed on his final sign, is just above the entrance to the restaurant. He told the owner that he did it for my mother, so that whenever she went there for dinner, she'd know he'd always be there with her.

Tyler Coates is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is a writer living in Chicago. He tumbls here and twitters here.

"This Is My House, This Is My Home (alternate version)" - We Were Promised Jetpacks (mp3)

"The Walls Are Wearing Thin" - We Were Promised Jetpacks (mp3)

"With the Benefit of Hindsight" - We Were Promised Jetpacks (mp3)

FILM

FILM  Thursday, April 1, 2010 at 11:58AM

Thursday, April 1, 2010 at 11:58AM

greenberg,

greenberg,  tyler coates

tyler coates