FILM

FILM In Which We Are An Ill-Suited Witness

Friday, December 11, 2009 at 11:35AM

Friday, December 11, 2009 at 11:35AM

Major Corporation

by RAYMOND ZHONG

Up in the Air

dir. Jason Reitman

109 minutes

Jason Reitman's new film Up in the Air is very likely not for you. It is not for you if you have a fast-paced career, and it is not for you if you do not. It is not for you if you've ever been laid-off, and it is not for you if you've ever considered taking another's hand in marriage. It is not for you if you cherish your isolated modern life, and it is certainly not for you if you loathe it.

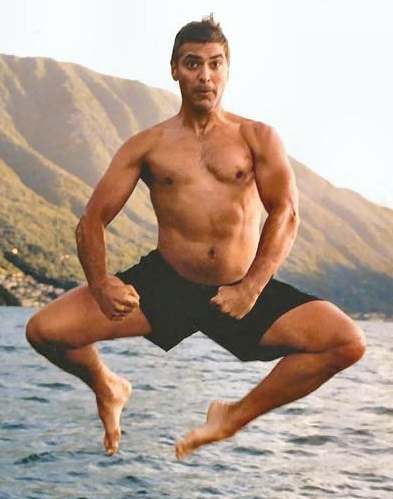

More likely Up in the Air is for those of us for whom major life decisions--do I marry? do I settle? - are possessed of exceptional orderliness, of such neat correspondence with your tastes and habits that attending to them is like selecting the color of your drapes. For George Clooney's Ryan Bingham, who charms and gallivants with Scrooge-like dastardliness, good solutions to life's problems come to him as air is drawn into a vacuum; there is nothing there in Ryan Bingham, the movie says, and so even something small seems like everything. But for the rest of us, our failings not so trimmed or well-shaped, that kind of inevitability is hard to imagine.

Up in the Air, according to its young director, “is the examination of a philosophy.” That philosophy is Bingham's, a survivalist samurai ethic that happily suits both his vocation and his personality. He's so fully a creature of what he does that he teaches it to others in motivational speeches.

For people in the business of inventing characters it's an irresistible trope: corporate life's starry promise that by actualizing certain strangers' interests - the firm's, the client's, the partners' - we in the process fulfill our own. But if you have spent any time at all in middling corporate office places you will know that it does not begin to describe the real complication of what happens there. It is color assigned to what is grayish and nebulous. We take jobs and pursue “career paths” that when the sun sets and we tuck in under our covers do not look very much like “paths” at all, let alone philosophies, warped as they are by the weight of our contradictions.

At the Major Corporation where I interned last summer, I worked under fluorescent lights with men and women who had postponed humanitarian ambitions and passed over MFAs in painting and dance. I sat one desk over from a prize-winning classical clarinetist who'd spurned conservatory for investment banking. Others rhapsodized about the outdoors and odd jobs in extreme geographies. “Dreams” was a disproportionate topic of conversation, and so was “Passions,” and “Priorities.”

At the Major Corporation where I interned last summer, I worked under fluorescent lights with men and women who had postponed humanitarian ambitions and passed over MFAs in painting and dance. I sat one desk over from a prize-winning classical clarinetist who'd spurned conservatory for investment banking. Others rhapsodized about the outdoors and odd jobs in extreme geographies. “Dreams” was a disproportionate topic of conversation, and so was “Passions,” and “Priorities.”

They come to inhabit us, our dreams and our passions and our priorities, and often I imagined that I had truly come to know a coworker once I could identify his one thing, the one motive force external to his work at Major Corporation that impelled him to keep showing up on Mondays. But in retrospect this expectation seems unreasonable. The man who is fully a creature of what he wants to do is as rare and strange as the man who is fully a creature of what he does.

Hours at Major Corporation were long. Dinner on many nights came, delivered, in plastic containers and takeout boxes. Down the hall a squarish industrial machine emitted watery coffee into paper cups. Many of the people I worked with had problems with these and other features of life at Major Corporation. But more did not, and for me what brought them in on Mondays was harder to pin down.

Some had married quickly, thoughtlessly. Some retreated into waste and decadence. Others, finding their youth and ambition attenuated, simply began to shift their energies toward what was right in front of them, on their desk. They were not pining for just that one last missing piece, they were not simply waiting “to make a connection.” Their lives were fistfuls of missing connections, none of them explaining why they weren't ever really going to leave their desks, of why nothing else along the way ever seemed quite as right for them.

This is the real hardship of corporate life, the possibility that despite ourselves we may actually be suited to little else. That in walking the path toward our dreams we realize that we would die in the water at conservatory or as a French chef or as an aid worker. These realizations involve real sacrifices, ones more severe than abandoning a lone-warrior philosophy and learning to love a little. In fact for many of us it is that we love too much or too many that poses problems: we really cannot have it all, and George Clooney, for all the contemplative gazing he does in this movie, is ill-suited as a witness to that fact.

Ryan Bingham circles the country 322 days out of the year, and so his inner life has come to echo his disconnected outer one. Perhaps as metaphor this is appealing. But many of us spend too much time up in the air even when we are planted at a desk, and for us it is not garish metaphor that will make meaningful sense of this experience, that will propose workable responses to adult life's real gasping difficulties.

Raymond Zhong is a contributor to This Recording. This is his first appearance in these pages. He is a writer living in Washington D.C. He tumbls here.

"Have Yourself A Merry Christmas" - Frank Sinatra (mp3)

"Go Tell It On The Mountain" - Frank Sinatra (mp3)

"We Wish You The Merriest" - Frank Sinatra (mp3)