BOOKS

BOOKS In Which Vladimir Nabokov Navigates Hell For Lolita

Wednesday, August 3, 2011 at 11:42AM

Wednesday, August 3, 2011 at 11:42AM

The Great Work

In an atmosphere of great secrecy, I shall show you — when I return east — an amazing book that will be quite ready by then.

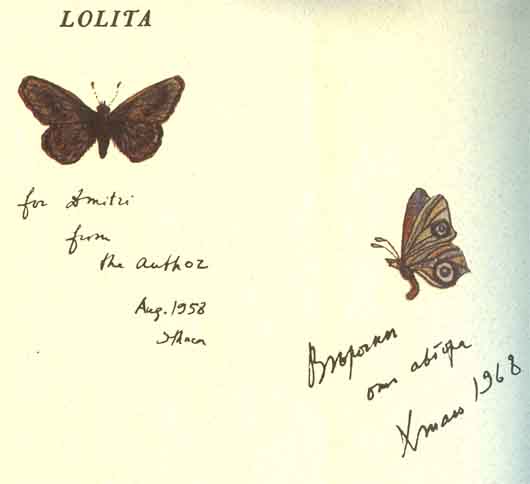

Lolita was created once and for all when Vladimir Nabokov decided to transition his novel about an emigre's love of a young girl into the first person from the third person. Even then, it had a terrible time finding someone brave enough to publish its biting satire. Ignored upon first publication, the comic novel was finally given momentum it would never lose when the English novelist Graham Greene named it one of his best books in 1955.

As the following letters prove, even Nabokov's closest friends, including the critic Edmund Wilson, did not fully understand what had been placed in their care. Perhaps sensing he was missing something, Wilson showed the book to his wife and his ex-wife. They both liked the book considerably more than Edmund. It was eventually published in America by Walter Minton at G.P. Putnam, who had heard about it from his girlfriend, a dancer in the Latin Quarter, and nothing would ever be the same again.

James Mason & Sue Lyon in Stanley Kubrick's "Lolita"Wilson's letter in October of 1953 precipitated Vladimir's first mention of Lolita:

James Mason & Sue Lyon in Stanley Kubrick's "Lolita"Wilson's letter in October of 1953 precipitated Vladimir's first mention of Lolita:

October 23, 1953

Wellfleet, Mass.

Dear Volodya,

I had been wondering what you were up to. We are no longer at Talcottville but back here. After Christmas, we are going to that old Europe, where I have been asked to perform during February at the Seminar of American Studies at Salzburg — expect to take in London and Paris on the way.

Here is a story that you ought to be told. Paul Brooks, the head of Houghton Mifflin, is an enthusiastic amateur naturalist. One day he opened his door and found a Polyphemus moth on his doorstep, a male. He was surprised, because, according to him, it was irregular to see one in Boston at that time of year. The moth came into the house, flew through some of the rooms and then departed. The same thing happened the next day and the day after that. After the third visit, Brooks remembered that he had a Polyphemus cocoon. When he went to the box in the drawer where he kept it, he found that a female had emerged. He put her outside on the sundial, and the male at once came and got her. They left him a little note saying that if at any time he should get into trouble with dragons or ogres, he had only to call upon them.

I have had a horrible two weeks of gout, but am over it and am otherwise prospering. I have been working on three major literary projects, but won't describe them, since the results will inevitably reach you.

The only publication that will pay anything much for poetry is the New Yorker. You know about the Atlantic and Harper's. Or do you mean that you want, as you ought, to publish a book of poems? If you do, I'm afraid that you'd have to engage to give them a novel or something, too. Love to Vera. Elena sends love.

Edmund Wilson

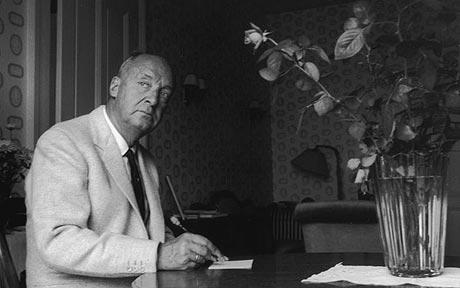

young nabokov Vladimir responds from New Mexico, where he reports on the novel's first rejections.

young nabokov Vladimir responds from New Mexico, where he reports on the novel's first rejections.

July 30, 1954

Taos, NM

Dear Bunny,

I have been wanting to write you for months but this has been, and still is, and will be for a long while yet, a time of great labors with me. First of all I want to thank you for your book of plays. I still think the Siniy Ogonyochek your best one in the way of harmony and multiple sense. I thought the Diabolic Play extraordinarily amusing and well done. Vera joins me in sending you her thanks and tokens of appreciation. Next, let me tell you I enjoyed hugely your Biblical Essay in the New Yorker and hope there is more to come.

I am now collecting butterflies in New Mexico. A dull series of events led us to rent by wire from Ithaca a house here. We are near a superb canyon where I go for my hunting, and twelve miles from Taos which is a dismal hole full of third-rate painters and faded pansies. The house cost only 250 dollars for the whole summer, and an orchard was thrown in. Unfortunately our Spanish neighbors take all the fruit and a colorful smell of drains pervades what is euphemistically called the patio. The mountains around us, though high enough for my purposes, are not interesting enough for Dmitri to climb. He is with us this summer but may go to the Tetons a little later. How are you spending the summer? Give us news about all of you. Will you be in New York in Mid-September? I have to deliver there on the 14th of Sept a lecture on the Art of Translation at the English Institute.

I have had to lay aside my Eugene Onegin work for other things.

One of them is an edition of Anna Karenina in English with my notes, commentaries, introductions, etc., for Simon and Schuster. They wanted a revision with notes for Part One first, and this I have just completed. With Viking I have signed a contract for my book on Pnin, but will not be able to finish it before the end of the winter.

The novel I had been working at for almost five years has been promptly turned down by the two publishers (Viking and S. & S.) I showed it to. They say it will strike readers as pornographic. I have now sent it to New Directions but it is unlikely they will take it. I consider this novel to be my best thing in English, and though the theme and situation are decidedly sensuous, its art is pure and its fun riotous. I would love you to glance at it some time. Pat Covici said we would all go to jail if the thing were published. I feel rather depressed about this fiasco. Another thing that has left me quite limp and hysterical is my Russian version of Conclusive Evidence which is appearing serially in the Novyi Zhurnal and will be published by the Chekhov firm in the fall.

Please, write me. Best love from both of us to Elena.

Yours,

V.

August 9, 1954

Talcottville, NY

Dear Volodya:

By all means, send me your book. I'd love to see it, and if nobody else is doing it, I'll try to get my publisher, Straus, to. I agree about Taos, but used to love the Jemez mountains — have you been there?

I expect to go to New York rather early in September, but don't expect to be there as late as the 14th. Isn't there any chance that you could come over here? It isn't so terribly far from Ithaca — about an hour's drive north of Utica. Elena and the children will leave on the 3rd, but I'll probably stay here till the Tuesday after Labor Day. It's been far too long since we've seen you.

I read your note to the Russian version of your memoirs and made some comparisons with the English text. There was something about it I was going to say to you, but haven't the book here and can't remember what it was. I'm still going to read your complete works, but thought I might not see them in perspective without some more intimate knowledge of the Bible. There are going to be two more of those articles.

Love from all our family to yours. Do try to come to see us here.

As ever,

EW

September 9, 1954

Ithaca, New York

Dear Bunny,

We had to leave Taos very suddenly. Vera fell ill (liver trouble) and the diagnosis reached by an Albuquerque doctor was so frightening that we all three made a dash for New York. The doctors there, however, after a thorough examination, pronounced Vera well — and we are now back in Ithaca.

Thanks for your nice letter — and for writing F. & S. about the thing. It is still in Laughlin's large hands. I am very anxious for you to read it, it is by far my best English work.

I shall be in N.Y.C. on the 14th of this month — to talk on Problems of Translation (Onegin in English) at the English Institute, Columbia Univ. This has been a hectic hash of a summer. Vera's illness and some other unexpected expenses have left me in a pitiful state of destitution and debt.

Yours,

V.

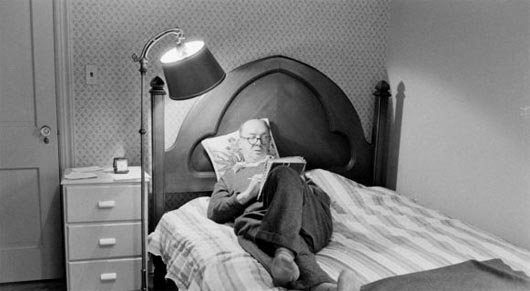

at 802 East Seneca Street in Ithaca This 1954 letter from Wilson contains his first reaction to Lolita.

at 802 East Seneca Street in Ithaca This 1954 letter from Wilson contains his first reaction to Lolita.

November 30, 1954

Wellfleet, Mass.

Dear Volodya:

Roger Straus lent me the MS of your book, and I read it when I was in New York — though rather hastily, because I had to give it back, and I have waited to write you about it till I could get some other opinions. I also had Elena and Mary read it. I enclose Mary's reactions from a letter to me, which she says I may quote to you. Elena seems to have liked the book better than either Mary or I — partly, I think, because she has seen America from the foreigner's point of view and understands how it looks to your hero. The little girl, for example, seems quite all right to her, though rather implausible to me.

I am afraid that you will never get the book published by anybody except perhaps Laughlin. I have, however, written about it to a man named Weldon Kees, a poet, who has just written me that he is associated with a new publishing venture in California, and that they want to bring out books of a kind that might otherwise not be published. I have also talked about it to Jason Epstein at Doubleday. It seems that, when they wiped out your part of the advance on that Russian book we were going to do, there was some sort of understanding that you would eventually submit a novel. Did you ever send them anything? I also suggested that he might be interested in your translation of Onegin for his paperback Anchor series. This has been a huge success, and I have been making money out of the two books of mine they have published. They would give you a big advance, but, as a paperback, the book might never get reviewed. To me, this doesn't matter a bit, and I am going to give them a collection of my essays on Russian subjects. If I were you, I'd send Epstein the Onegin when you finish it. He's a highly intelligent boy, very well read and with a good deal of taste.

Now, about your novel: I like it less than anything else of yours I have read. The short story that it grew out of was interesting, but I don't think the subject can stand this very extended treatment. Nasty subjects may make fine books; but I don't feel you have got away with this. It isn't merely that the characters and the situation are repulsive in themselves, but that, presented on this scale, they seem quite unreal. The various goings-on and the climax at the end have, for me, the same fault as the climaxes of Bend Sinister and Laughter in the Dark: they become too absurd to be horrible or tragic, yet remain too unpleasant to be funny. I think, too, that in this book there is-what is unusual with you-too much background, description of places, etc. This is one thing that makes me agree with Roger Straus in feeling that the second half drags. I agree with Mary that the cleverness sometimes becomes tiresome, though I don't think I agree with her about the "haziness." (I have suggested a few minor corrections on the MS.)

I wish I could like the book better. I am sorry that we see so little of you. We're going to be in New York for a week beginning December 15. If you're coming on for the holidays, let us know. We'll probably be staying at the Algonquin, but if we're not, you can reach me at the New Yorker office.

As ever,

EW

Wilson passed along a few notes from his ex-wife Mary McCarthy about her impressions of the novel.

About Vladimir's book — I think I have a midway position. I say think because I didn't quite finish it; I was three-quarters through the second volume when we had to leave. At Roger Straus' instructions, I left it at the Chelsea for Philip Rahv to pick up — he may run some of the first part in PR. I don't agree with you that the second volume was boring. Mystifying, rather, it seemed to me; I felt it had escaped into some elaborate allegory or series of symbols that I couldn't grasp.

Bowden suggests that the nymphet is a symbol of America, in the clutches of the middle-aged European (Vladimir); hence all the descriptions of motels and other U.S. phenomenology (I liked this part, by the way). But there seems to be some more concrete symbolism, in the second volume; you felt all the characters had a kite of meaning tugging at them from above, in Vladimir's enigmatic empyrean. What about that pursuer, for instance? I thought maybe I'd find the answer if I finished it — is there one?

On the other hand, I thought the writing was terribly sloppy all through, perhaps worse in the second volume. It was full of what teachers call haziness, and all Vladimir's hollowest jokes and puns. I almost wondered whether this wasn't deliberate — part of the idea.

Edmund Wilson's fourth wife, Elena, had a more impressive reaction to the novel.

November 30, 1954

Wellfleet, Mass.

Dear Vladimir:

The little girl seems very real and accurate and her attractiveness and seductiveness are absolutely plausible. The hero's disgust of grown-up women is not very different, for example, from Gide's, the difference being that Gide is smug about it and your hero is made to go through hell. The suburban, hotel, motel descriptions are just terribly funny.

I don't see why the novel should be any more shocking than all the now commonplace "etudes of other unpleasant moeurs." These peculiar tastes are surely as prevalent even if they haven't been written about as often. Why shouldn't the book be published in England, or certainly in France and then come back here in a somewhat expurgated form and be read greedily?

Unfortunately, my opinion is very unimportant. We would love to see you soon. Please give my love to Vera.

In other words, I couldn't put the book down and think it is very important.

Elena

February 19, 1955

Ithaca, New York

Dear Elena and Bunny,

Belatedly but with perfectly preserved warmth I now want to thank you for your letters — Elena's was especially charming.

Doubleday has of course returned the MS and I have now shipped it to France. I suppose it will be finally published by some shady firm with a Viennese-Dream name — e.g., "Silo."

(I did show Doubleday not one book but at least two or three — the last I can remember was Bend Sinister for Permabooks, on their request, when a man of the name of McKay or something like it was in charge; before Epstein took over.)

I have been completely immersed in Onegin during these last months. I have finished the translation of the text and of all variants I could find, but the commentaries are voluminous and their arrangement in readable form will take me many months. Doubleday was not interested in publishing the thing in the form I want it to appear in, with the notes running to at least 400 pages, and the Russian text en regard. I have found all kinds of sensational analogies, etc., in English and French literatures, and have solved the mystery of the master motto.

Bunny, I liked very much your Palestine essay. It is one of your best pieces.

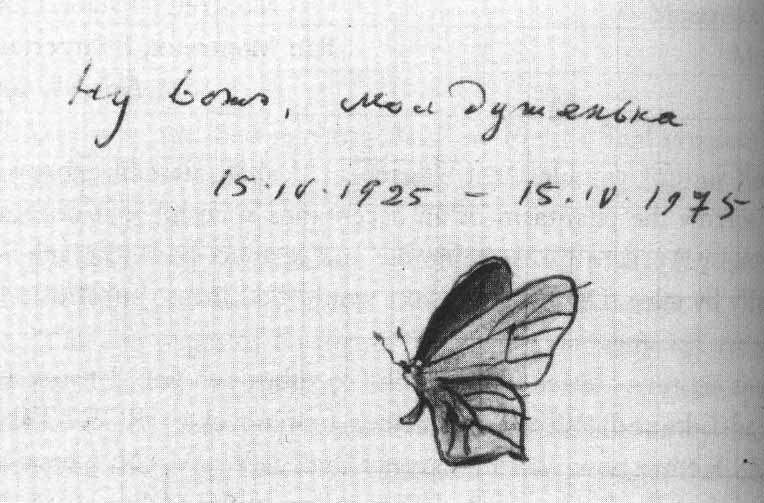

This has been, and still is, a difficult winter for us. My financial woes have not been allayed by my concentrating on Lolita and Onegin. My novel about the Russian professor Pnin is progressing very slowly. Another chapter has been bought by the New Yorker.

Dmitri is finishing Harvard this spring. Our plans for the summer are extremely hazy. I am taking a semi-sabbatical next spring semester. Vera and I miss you.

V

1955 corrections to the manuscript of LolitaIn this letter, Nabokov finally lashes out at his friend for not understanding his finest work.

1955 corrections to the manuscript of LolitaIn this letter, Nabokov finally lashes out at his friend for not understanding his finest work.

November 24, 1955

Dear Bunny,

It was a pleasure seeing you but our meeting was much too brief. Rahv, who had offered to print parts of my little Lolita in the Partisan, has changed his mind upon the advice of a lawyer. It depresses me to think that this pure and austere work may be treated by some flippant critic as a pornographic stunt. This danger is the more real to me since I realize that even you neither understand nor wish to understand the texture of this intricate and unusual production.

Our plans are to spend some six weeks of my sabbatical half-year in Cambridge, arriving there early in February, after which we shall probably drive to California, and return to Cornell in September. We are looking forward to seeing you and Elena in Cambridge.

We regret so much not having been able to join you in Boston for Thanksgiving.

Yours ever,

V.

This is the second in a series. You can find the first part here.

"This Is Not A Song, It's An Outburst, or, The Establishment Blues" - Rodriguez (mp3)

"Like Janis" - Rodriguez (mp3)

"Only Good For Conversation" - Rodriguez (mp3)

"Sugar Man" - Rodriguez (mp3)

directing Sue Lyon

directing Sue Lyon

edmund wilson,

edmund wilson,  vladimir nabokov

vladimir nabokov