Her Triumph

Sex is the great leveler, taste the great divider.

Reading the reviews of Pauline Kael is a pleasure not only because of how often she was right (except with Blade Runner), in retrospect, about what actually made a movie good. It is rewarding because of her descriptions of actresses and actors. Beyond taking them to task for their mere talent, she was able to describe the effect they had on people through their continuing cinematic presence. Kael properly deduced that a huge part of going to the movies consisted of how the audience responded to the people on the screen, rather than simply basing her critique on the competence of the writing or the technical aspects of the cinematography. Her sentences in her radio and print reviews about the onscreen talent of the twentieth century rise to the level of expert observation of humanity in all its manifold variety. Here are a few of my favorite descriptions. - A.C.

Marilyn Monroe

Her mixture of wide-eyed wonder and cuddly drugged sexiness seemed to get to just about every male; she turned on even homosexual men. And women couldn't take her seriously enough to be indignant; she was funny and impulsive in a way that made people feel protective. She was a little knocked out; her face looked as if, when nobody was paying attention to her, it would go utterly slack — as if she died between wolf calls.

She seemed to have become a camp siren out of confusion and ineptitude; her comedy was self-satire, and apologetic — conscious parody that had begun unconsciously. She was not the first sex goddess with a trace of somnabulism; Garbo was often a litte out-of-it, Dietrich was numb most of time, and Hedy Lamarr was fairly zonked. But they were exotic and had accents, so maybe audiences didn't wonder why they were in a daze; Monroe's slow reaction time made her seem daffy, and she tricked it up into a comedy style. The mystique of Monroe — which accounts for the book Marilyn — is that she became spiritual as she fell apart. But as an actress she had no way of expressing what was deeper in her except in moodiness and weakness. When she was "sensitive" she was drab.

Paul Newman

Somehow it all reminds one of the old apocryphal story conference — "It's a modern western, see, with this hell-raising, pleasure-loving man who doesn't respect any of the virtues, and, at the end, we'll fool them, he doesn't get the girl and he doesn't change!"

"But who'll want to see that?"

"Oh, that's all fixed — we've got Paul Newman for the part."

They could cast him as a mean man and know that the audience would never believe in his meanness. For there are certain actors who have such extraordinary audience rapport that the audience does not believe in their villainy except to relish in it, as with Brando; and there are others, like Newman, who in addition to this rapport, project such a traditional heroic frankness and sweetness that the audience dotes on them, seeks to protect them from harm or pain. Casting Newman as a mean materialist is like writing a manifesto against the banking system while juggling your investments so you can break the bank.

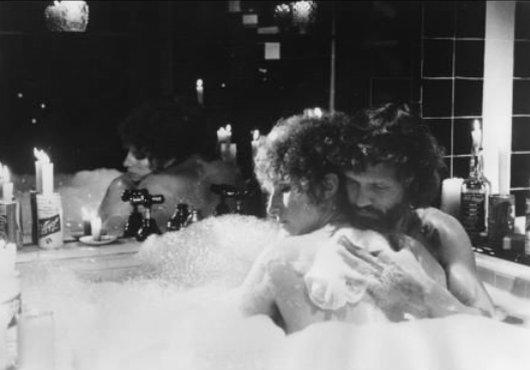

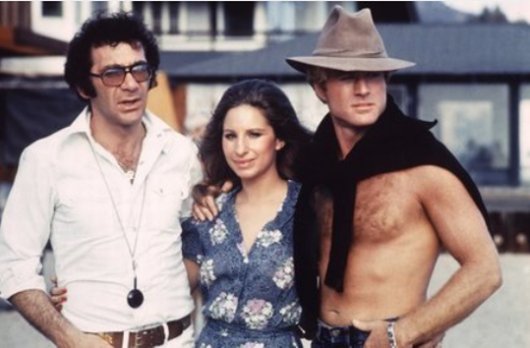

Barbra Streisand

As Streisand's pictures multiply, it becomes apparent that she is not about to master an actress's craft but, rather, is discovering a craft of her own, out of the timing and emotionality that make her a phenomenon as a singer. You admire her not for her acting — or singing — but for herself, which is what you feel she gives you in both. She has the class to be herself, and the impudent music of her speaking voice is proof that she knows it. The audacity of her self-creation is something we've had time to adjust to; we already knew her mettle, and the dramatic urgency she can bring to roles.

In Up the Sandbox, she shows a much deeper and warmer presence and a freely yielding quality. And a skittering good humor — as if, at last, she had come to accept her triumph, to believe in it. That faint weasellike look of apprehensiveness is gone — and that was what made her seem a little frightening. She is a great undeveloped actress — undeveloped in the sense that you feel the natural richness in her but can see that she's idiocsyncratic and that she hasn't the training to play the classical roles that still define how an actress's greatness is expressed. But in movies new ways may be found.

Warren Beatty

There is a story told against Beatty in a recent Esquire — how during the shooting of Lilith he "delayed a scene for three days demanding the line 'I've read Crime and Punishment and The Brothers Karamazov' be changed to 'I've read Crime and Punishment and half of The Brothers Karamazov.'" Considerations of professional conduct aside, what is odd is why his adversaries waited three days to give in, because, of course, he was right. That's what the character he played should say; the other way, the line has no point at all. But this kind of intuition isn't enough to make an actor, and in a number of roles Beatty, probably because he doesn't have the technique to make the most of his lines in the least possible time, has depended too much on intuitive non-acting — holding the screen far too long as he acted out self-preoccupied characters in a lifelike, boringly self-conscious way...

The role of Clyde Barrow seems to have released something in him. As Clyde, Beatty is good with his eyes and mouth and his hat, but his body is still inexpressive; he doesn't have a trained actor's use of his body, and, watching him move, one is never for a minute convinced he's impotent.

Cary Grant

Cary Grant is the male love object. Men want to be as lucky and enviable as he is — they want to be like him. And women imagine landing him. Like Robert Redford, he's sexiest in pictures in which the woman is the aggressor and all the film's erotic energy is concentrated on him, a sit was in Notorious: Ingrid Bergman practically ravished him while he was trying to conduct a phone conversation...

Many men must have wanted to be Clark Gable and look straight at a woman with a faint smirk and lifted, questioning eyebrows. What man doesn't — at some level — want to feel supremely confident and earthy and irresistible? But a few steps up the dreamy social ladder there's the more subtle fantasy of worldly grace — of being so gallant and gentlemanly and charming that every woman longs to be your date. And at that deluxe level men want to be Cary Grant. Men as far apart as John F. Kennedy and Lucky Luciano thought that he should star in their life story. Who but Cary Grant could be a fantasy self-image for a president and a gangster chief? Who else could demonstrate that sophistication didn't have to be a sign of weakness — that it could be the polished, fun-loving style of those who were basically tough? Cary Grant has said that even he wanted to be Cary Grant.

Katharine Hepburn

There were occasions in the past when Hepburn had poor roles and was tremulous and affected — almost a caricature of quivering sensitivity. But at her best — in the archetypal Hepburn role as the tomboy Linda in Holiday, in 1938 — her wit and nonconformity made ordinary heroines seem mushy, and her angular beauty made the round-faced ingénues look piggy and stupid. She was hard where they were soft — in both head and body. (As Spencer Tracy said, in the Brooklyn accent he used in Pat and Mike, "There's not much meat on her, but what's there is cherce." Other actresses could be weak and helpless, but Davis and Hepburn had too much vitality.

Unlike Davis, Hepburn was limited to mandarin roles, although some of her finest performances were as poor girls who were mandarins by nature, as in Little Women and Alice Adams, rather than by birth or wealth, as in Bringing Up Baby and in the movie that the public liked her best in, The Philadelphia Story (even if her dedicated admirers, including me, tended to be less wild about it). Hepburn has always been inconceivable as a coarse-minded character; her bones are too fine, her diction is too crisp, she wears clothes too elegantly. And she has always been too individualistic, too singular, for common emotions. Other actresses who played career girls, like Crawford, could cop out in their roles by getting pregnant, or just by turning emotional — all womanly and ghastly. Hepburn was too hard for that, and so one could go to see her knowing that she wouldn't deteriorate into a conventional heroine that didn't suit her style...

When an actress has been a star for a long time, we know too much about her; for years we have been hearing about her romances or heartbreaks, or whatever the case may be, and all this carries over into her presence on the screen. And if she uses this in a role, she's sunk. When actresses begin to use our knowledge about them and of how young and beautiful they used to be — when they offer themselves up as ruins of their former selves — they may get praise and awards (and they generally do), but it's not really for their acting, it's for capitulating and giving the public what it really wants: a chance to see how the mighty have fallen.

Meryl Streep

Meryl Streep just about always seems miscast. (She makes a career out of seeming to overcome being miscast.) In Postcards from the Edge, she's witty and resourceful, yet every expression is eerily off, not quite human. When she sings in a country-and-Western style, she's note-perfect, but it's like a diva singing jazz — you don't believe it. Streep has a genius for mimicry: she's imitating a country-and-Western singer singing. These were my musings to a friend, who put it more simply: "She's an android." Yes, and it's Streep's android quality that gives Postcards whatever interest i

This tale of sorrowful, wisecracking starlet whose brassy, boozing former-star mother (Shirley MacLaine) started her on sleeping pills when she was nine is without the zest of camp. It's camp played borderline straight — a druggy-Cinderella movie about an unformed girl who has to go past despair to find herself. The director, Mike Nichols, is a parodist who feigns sincerity, and his tone keeps slipping around. What's clear is that we're meant to adore the daughter, who is wounded by her mother's cheap competitiveness. Nichols wants us to be enthralled by the daughter's radiant face, her refinement, her honesty. He keeps the camera on Streep as if to prove that he can make her a popular big star — a new Crawford or Bette Davis. (She remains distant, emotionally atonal.)

Replying to Listeners

by PAULINE KAEL

I am resolved to start the New Year right; I don't want to carry over any unnecessary rancor from 1962. So let me discharge a few debts. I want to say a few words about a communication from a woman listener. She begins with, "Miss Kael, I assume you aren't married — one loses that nasty, sharp bite in one’s voice when one learns to care about others."

Isn’t it remarkable that women, who used to pride themselves on their chastity, are now just as complacently proud of their married status? They’ve read Freud and they’ve not only got the illusion that being married is healthier, more "mature," they’ve also got the illusion that it improves their character. This lady is so concerned that I won’t appreciate her full acceptance of femininity that she signs herself with her husband’s name preceded by a Mrs. Why, if this Mrs. John Doe just signed herself Jane Doe, I might confuse her with one of those nasty virgins, I might not understand the warmth and depth of connubial experience out of which she writes.

I wonder, Mrs. John Doe, in your reassuring, protected marital state, if you have considered that perhaps caring about others may bring a bite to the voice? And I wonder if you have considered how difficult it is for a woman in this Freudianized age, which turns out to be a new Victorian age in its attitude to women who do anything, to show any intelligence without being accused of unnatural aggressivity, hateful vindictiveness, or lesbianism. The latter accusation is generally made by men who have had a rough time in an argument; they like to console themselves with the notions that the woman is semi-masculine. The new Freudianism goes beyond Victorianism in its placid assumption that a woman who uses her mind is trying to compete with men. It was bad enough for women who had brains to be considered freaks like talking dogs; now it’s leeringly assumed that they’re trying to grow a penis — which any man will tell you is an accomplishment that puts canine conversation in the shadows.

Mrs. John Doe and her sisters who write to me seem to interpret Freud to mean that intelligence, like a penis, is a male attribute. The true woman is supposed to be sweet and passive — she shouldn’t argue or emphasize and opinion or get excited about a judgment. Sex — or at least regulated marital sex — is supposed to act as a tranquilizer. In other words, the Freudianized female accepts that whole complex of passivity that the feminists battled against.

Mrs. Doe, you know something, I don't mind sounding sharp — and I’ll take my stand with those pre-Freudian feminists; and you know something else, I think you’re probably so worried about competing with male egos and those brilliant masculine intellects that you probably bore men to death.

This lady who attacks me for being nasty and sharp goes on to write, "I was extremely disappointed to hear your costic speech on and about the radio station, KPFA. It is unfortunate you were unable to get a liberal education, because that would have enabled you to know that a great many people have many fields of interest, and would have saved you from displaying your ignorance on the matter." She, incidentally, displays her liberal education by spelling caustic c-o-s-t-i-c, and it is with some expense of spirit that I read this kind of communication. Should I try to counter my education — liberal and sexual—against hers, should I explain that Pauline Kael is the name I was given at birth, and that it does not reflect my marital vicissitudes which might over-complicate nomenclature?

It is not really that I prefer to call myself by my own name and hence Miss that bothers her or the other Mrs. Does, it is that I express ideas she doesn’t like. If I called myself by three names like those poetesses in the Saturday Review of Literature, Mrs. Doe would still hate my guts. But significantly she attacks me for being a Miss. Having become a Mrs., she has gained moral superiority: for the modern woman, officially losing her virginity is a victory comparable to the Victorian woman’s officially keeping hers. I’m happy for Mrs. Doe that she’s got a husband, but in her defense of KPFA she writes like a virgin mind. And is that really something to be happy about?

Mrs. Doe, the happily, emotionally-secure-mature-liberally-educated-womanly-woman has her opposite number in the mailbag. Here is a letter from a manly man. This is the letter in its entirety:

Dear Miss Kael,

Since you know so much about the art of the film, why don’t you spend your time making it? But first, you will need a pair of balls.

Mr. Dodo (I use the repetition in honor of your two attributes), movies are made and criticism is written by the use of intelligence, talent, taste, emotion, education, imagination, and discrimination. I suggest it is time you and your cohorts stop thinking with your genital jewels. There is a standard answer to this old idiocy of if-you-know-so-much-about-the-art-of-the-film-why-don’t-you-make-movies. You don’t have to lay an egg to know if it tastes good. If it makes you feel better, I have worked making movies, and I wasn’t hampered by any biological deficiencies.

Others may wonder why I take the time to answer letters of this sort: the reason is that these two examples, although cruder than most of the mail, simply carry to extremes the kind of thing so many of you write. There are, of course, some letter writers who take a more “constructive” approach. I’d you to read you part of a long letter I received yesterday:

I haven’t been listening to your programs for very long and haven’t heard all of them since I began listening … But I must say that while I have been listening, I have not heard one favorable statement made of any “name” movie made in the last several years…. I have heard no movie which received any kind of favorable mention which was not hard to find playing, either because of its lack of popularity or because of its age. In your remarks the other evening about De Sica’s earlier movies you praised them all without reservation until you mentioned his "most famous film — The Bicycle Thief, a great work, no doubt, though I personally find it too carefully and classically structured." You make me think that the charge that the favorability of your comments on any given movie varies inversely with its popularity, is indeed true even down to the last nuance.

But even as I write this, I can almost feel you begin to tighten up, to start thinking of something to say to show that I am wrong. I really wish you wouldn’t feel that way. I would much rather you leaned back in your chair, looked up at the ceiling and asked yourself, “Well, how about it? Is it true or not? Am I really biased against movies other people like, because they liked them? When I see a popular movie, do I see it as it is or do I really just try to pick it apart?” You see, I’m not like those other people that have been haranguing you. I may be presumptuous, but I am trying sincerely to be of help to you. I think you have a great deal of potential as a reviewer…. But I am convinced that great a potential as you have, you will never realize any more of that potential than you have now until you face those questions mentioned before, honestly, seriously, and courageously, no matter how painful it may be. I want you to think of these questions, I don’t want you to think of how to convince me of their answers. I don’t want you to look around to find some popular movie to which you can give a good review and thus “prove me wrong.” That would be evading the issue of whether the questions were really true or not. Furthermore, I am not “attacking” you and you have no need to defend yourself to me.

May I interrupt? Please, attack me instead — it’s this kind of “constructive criticism” that misses the point of everything I’m trying to say that drives me mad. It’s enough to make one howl with despair, this concern for my potential — as if I were a cow giving thin milk. But back to the letter—

In fact, I would prefer that you make no reply to me at all about the answers to these questions, since I have no need of the answers and because almost any answer given now, without long and thoughtful consideration, would almost surely be an attempt to justify yourself, and that’s just what you don’t have to do, and shouldn’t do. No one needs to know the answers to these questions except you, and you are the only person who must answer. In short, I would not for the world have you silence any voices in you … and most certainly not a concerned little voice saying, “Am I really being fair? Do I see the whole movie or just the part I like—or just the part I don’t like?"

And so on he goes for another few paragraphs. Halfway through, I thought this man was pulling my leg; as I got further and read "how you missed the child-like charm and innocence of The Parent Trap … is quite beyond me," I decided it’s mass culture that’s pulling both legs out from under us all. Dear man, the only real question you letter made me ask myself is, “What’s the use?” and I didn’t lean back in my chair and look up at the ceiling, I went to the liquor cabinet and poured myself a good stiff drink.

How completely has mass culture subverted even the role of the critic when listeners suggest that because the movies a critic reviews favorably are unpopular and hard to find, that the critic must be playing some snobbish game with himself and the public? Why are you listening to a minority radio station like KPFA? Isn’t it because you want something you don’t get on commercial radio? I try to direct you to films that, if you search them out, will give you something you won’t get from The Parent Trap.

You consider it rather “suspect” that I don’t raise more “name” movies. Well, what makes a “name” movie is simply a saturation advertising campaign, the same kind of campaign that puts samples of liquid detergents at your door. The “name” pictures of Hollywood are made the same way they are sold: by pretesting the various ingredients, removing all possible elements that might affront the mass audience, adding all possible elements that will titillate the largest number of people. As the CBS television advertising slogan put it—“Titillate—and dominate.” South Pacific is seventh in Variety’s list of all-time top grossers. Do you know anybody who thought it was a good movie? Was it popular in any meaningful sense or do we just call it popular because it was sold? The tie-in campaign for Doris Day in Lover Come Back included a Doris Day album to be sold for a dollar with a purchase of Imperial margarine. With a schedule of 23 million direct mail pieces, newspaper, radio, TV and store ads, Lover Come Back became a “name” picture.

I try not to waste air time discussing obviously bad movies — popular though they may be; and I don’t discuss unpopular bad movies because you’re not going to see them anyway; and there wouldn’t be much point or sport in hitting people who are already down. I do think it’s important to take time on movies which are inflated by critical acclaim and which some of you might assume to be the films to see.

There were some extraordinarily unpleasant anonymous letters after the last broadcast on The New American Cinema. Some were obscene; the wittiest called me a snail eating the tender leaves off young artists. I recognize your assumptions: the critic is supposed to be rational, clever, heartless and empty, envious of the creative fire of the artists, and if the critic is a woman, she is supposed to be cold and castrating. The artist is supposed to be delicate and sensitive and in need of tender care and nourishment. Well, this nineteenth-century romanticism is pretty silly in twentieth-century Bohemia.

I regard criticism as an art, and if in this country and in this age it is practiced with honesty, it is no more remunerative than the work of an avant-garde film artist. My dear anonymous letter writers, if you think it is so easy to be a critic, so difficult to be a poet or a painter or film experimenter, may I suggest you try both? You may discover why there are so few critics, so many poets.

Some of you write me flattering letters and I’m grateful, but one last request: if you write me, please don’t say, "This is the first time I've ever written a fan letter." Don’t say it, even if it's true. You make me feel as if I were taking your virginity — and it’s just too sordid.

You can find more by Pauline Kael here.

"There Is No God" - Bonnie Prince Billy (mp3)

"God Is Love" - Bonnie Prince Billy (mp3)

"For Every Field There Is A Mole" - Bonnie Prince Billy (mp3)

FILM

FILM  Thursday, February 23, 2017 at 10:10AM

Thursday, February 23, 2017 at 10:10AM

In the last year of his life, Howard Hughes focused his efforts on two of his favorite pastimes: taking drugs and watching movies. His two most important drugs were Valium and a laxative called Surfak, and he took them both in incredible quantities. In order to relieve constipation, you were supposed to take maybe one Surfak over the course of a day or two. Hughes would take ten or twenty over that period. His prostate gland swelled to over three times normal size. His kidneys shrank in fear.

In the last year of his life, Howard Hughes focused his efforts on two of his favorite pastimes: taking drugs and watching movies. His two most important drugs were Valium and a laxative called Surfak, and he took them both in incredible quantities. In order to relieve constipation, you were supposed to take maybe one Surfak over the course of a day or two. Hughes would take ten or twenty over that period. His prostate gland swelled to over three times normal size. His kidneys shrank in fear.