BOOKS

BOOKS In Which A Good Writer Has No Faults Only Sins

Tuesday, February 1, 2011 at 10:38AM

Tuesday, February 1, 2011 at 10:38AM

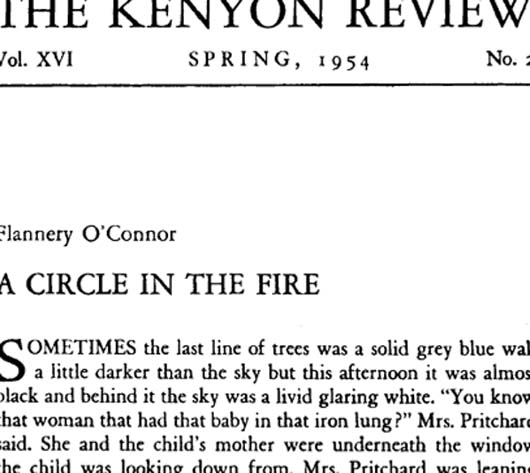

How and Why To Write

On any given morning Flannery O'Connor would just wake up and bust out a short story, for example "A Circle in the Fire" ("Sometimes the last line of trees was a solid grey blue wall a little darker than the sky...") and that was it. She really didn't have to do anything else during the day. One morning she was like, "I have some opinions about the Holocaust, and bam, "The Displaced Person." We could all stand to be a lot more like her, although that can never be, since she knew nothing of the internet.

Please revisit the first three parts of this series below:

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

Flannery O'Connor

Point of view drives me crazy when I think about it but I believe that when you are writing well, you don't think about it. I seldom think about it when I am writing a short story, but on the novel it gets to be a considerable worry. There are so many parts of the novel that you have to get it over with so you can get something else to happen, etc, etc. I seem to stay in a snarl with mine.

Of course I hear the complaint over and over that there is no sense in writing about people who disgust you. I think there is; but the fact is that the people I write about certainly don't disgust me entirely though I see them from a standard of judgment from which they fall short. Your freshman who said there was something religious here was correct. I take the Dogmas of the Church literally and this, I think, is what creates what you call the "missing link." The only concern, so far as I see it, is what Tillich calls "the ultimate concern." It is what makes the stories spare and what gives them any permanent quality they may have.

I beat my brains out this morning on a story I am hacking at and in the afternoon and I am exhausted is why I haven't got down to the typewriter. It takes great energy to typewrite something. When I typewrite something the critical instinct operates automatically and that slows me down. When I write it by hand, I don't pay much attention to it....

There is really one answer to the people who complain about one's writing about "unpleasant" people — and that is that one writes what one can. Vocation implies limitation but few people realize it who don't actually practice an art.

I don't know how you would tell anybody his writing was mannered, except you say, "Brother this is mannered." I once had the sentence: "He ran through the field of dead cotton" and Allen Tate told me it was mannered; should have been "dead cotton field." I don't hold that against Allen. Give him something good to criticize and he would do better.

I hope you don't have friends who recommend Ayn Rand to you. The fiction of Ayn Rand is as low as you can get re: fiction. I hope you picked it up off the floor of the subway and threw it in the nearest garbage pail. She makes Mickey Spillane look like Dostoevsky.

Charles Baxter

In day-to-day life we play these little games of comparison-contrast in which we are usually the contrast. I wouldn't have done it that way. Look at him, now, the one who did it, sinking. At least it wasn't me! By telling stories in this manner, we become narratable. We find a story for ourselves. We spin around ourselves, in what seems to be a natural form, the cobweb of a plot. We move our own lives into the condition of narrative progression. Plot often develops out of the tensions between characters, and in order to get that tension, a writer sometimes has to be a bit of matchmaker, creating characters who counterpoint one another in ways that are fit for gossip. Our hapless friend is character, but not yet my character. With counterpointed characterization, certain kinds of people are pushed together, people who bring out a crucial response to each other. A latent energy rises to the surface, the desire or secret previously forced down into psychic obscurity.

It seeks to be in the nature of plots to bring a truth or a desire up to the light, and it has often been the task of those who write fiction to expose elements that are kept secret in a personality, so that the mask over that personality (or any system) falls either temporarily or permanently. When the mask falls, something of value comes up. Masks are interesting partly for themselves and partly for what they mask. The reality behind the mask is like a shadow-creature rising to the bait: the tug of an unseen force, frightening and energetic. What emerges is a precious thing, precious because buried or lost or repressed.

Anyone who writes stories or novels or poems with some kind of narrative structure often imagines a central character, then gives that character a desire or a fear and perhaps some kind of goal and sets another character in a collision course with that person. The protagonist collides with an antagonist. All right: We know where we are. We often talk about this sort of dramatic conflict as if it were all unitary, all one of a kind: One person wants something, another person wants something else, and conflict results. But this is not, I think, the way most stories actually work. Not everything is a contest. We are not always fighting our brothers for our share of worldly goods. Many good stories have no antagonist at all.

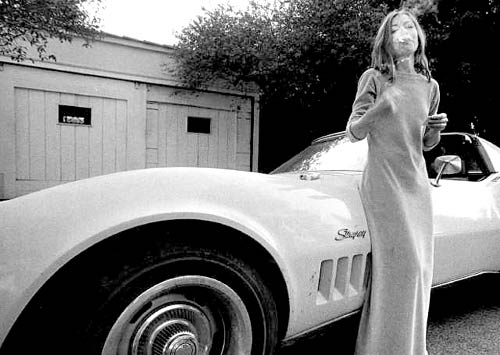

Joan Didion

The most important is that I need an hour alone before dinner, with a drink, to go over what I've done that day. I can't do it late in the afternoon because I'm too close to it. Also, the drink helps. It removes me from the pages. So I spend this hour taking things out and putting other things in. Then I start the next day by redoing all of what I did the day before, following these evening notes. When I'm really working I don't like to go out or have anybody to dinner, because then I lose the hour. If I don't have the hour, and start the next day with just some bad pages and nowhere to go, I'm in low spirits. Another thing I need to do, when I'm near the end of the book, is sleep in the same room with it. That's one reason I go home to Sacramento to finish things. Somehow the book doesn't leave you when you're asleep right next to it. In Sacramento nobody cares if I appear or not. I can just get up and start typing.

w.b. yeats (left) with andre gide (right)

w.b. yeats (left) with andre gide (right)

William Butler Yeats

In Paris Synge once said to me, "We should unite stoicism, asceticism and ecstasy. Two of them have often come together, but the three never."

I notice that in dreams our apparent subjective moods are almost limited to very elementary fear, grief, and desire. We are without complexity or any general consciousness of our state. If we are ill, our discomfort is transferred apparently from ourselves to the dream image. An image created by sexual desire, when our health is bad, may for instance be a woman with a swollen face, or some disagreeable behaviour. Indeed, when we are ill we often see deformed images. I suggest analogy between the form of the mind of the control, also superficial, and our apparent mind in dreams. The sense of identity is attenuated in both at the same points.

A good writer should be so simple that he has no faults, only sins.

Lyn Hejinian

Because we have language we find ourselves in a special and peculiar relationship to the objects, events and situations which constitute what we imagine of the world. Language generates its own characteristics in the human psychological and spiritual conditions. Indeed, it is near our psychological condition. This psychology is generated by the struggle between language and that which it claims to depict or express, by our overwhelming experience of the vastness and uncertainty of the world, and by what often seems to be the inadequacy of the imagination that longs to know it - and, furthermore, for the poet, the even greater inadequacy of the language that appears to describe, discuss, or disclose it. This psychology situates desire in the poem itself, or, more specifically, in poetic language, to which then we may attribute the motive for the poem.

Language is one of the principal forms our curiosity takes. It makes us restless. As Francis Ponge puts it, "Man is a curious body whose center of gravity is not in himself." Instead it seems to be located in language, by virtue of which we negotiate our mentalities and the world; off-balance, heavy at the mouth, we are pulled forward.

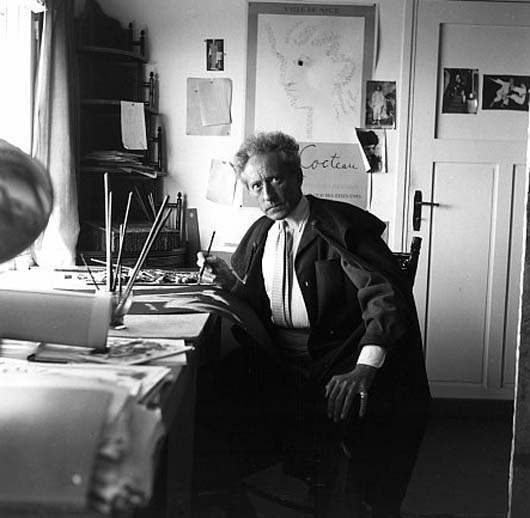

Jean Cocteau

I must make a disagreeable confession. I read nothing within the lines of my work. I find it very disconcerting; I disorient “the other.” I have not looked at a newspaper in twenty years; if one is brought into the room, I flee. This is not because I am indifferent but because one cannot follow every road. And nevertheless such a thing as the tragedy of Algeria undoubtedly enters into one's work, doubtless plays its role in the fatigued and useless state in which you find me. Not that “I do not wish to lose Algeria!” but the useless killing, killing for the sake of killing. In fear of the police, men keep to a certain conduct; but when they become the police they are terrible. No, one feels shame at being a part of the human race. About novels: I read detective fiction, espionage, science fiction.

francine du plessix gray w/ jonathan williams at black mountain

francine du plessix gray w/ jonathan williams at black mountain

Francine du Plessix Gray

Recently the compulsion has been less intense, a week or two can go by and then I catch up in my big streak: angers and anxieties and sarcastic reports on overhead conversations, any snazzy metaphors that come to mind, phrases and ideas for current projects, a lot of nature notes — smells, sounds, colors, birds. I sometimes wonder why I have to look back and record precisely what I was experiencing on such and such a day. No one’s given a satisfactory explanation for this compulsion writers have to keep a laundry list of the soul: Virginia Woolf, her need to jot down who came to tea every day, and the pitch of Lytton Strachey’s voice and the kind of cucumber sandwiches she served. It’s as if we feel constantly other from the person we were the day, the hour before, and this sense of flux is terrifying, we have to crystallize, fix every moment of ourselves in order not to disappear altogether, as if our very identity were constantly threatened with dissolution.

I get up fairly early and have an overabundant physical energy in the early hours, even without caffeine, which I gave up decades ago. I’m rather like a hyperactive child in the morning, it’s very hard for me to sit still and concentrate on any writing then. So those hours are reserved for the more passive work: reading what I call my sacred texts, poetry or the Bible or the classics; recently I’ve gone through Lattimore’s translation of Homer, and Virgil’s Aeneid in the Fitzgerald translation, and a history of the cabala.

Then after this most treasured hour of the day, which I always spend alone upstairs in my room, with some tea and fruit and honey, I go about the business of life: notes to friends, shopping and planning for the family, answering phone calls, thanking people for this and that, thanking the world. As if I have to earn the right to write by being a good girl—all about me must be perfectly rinsed and dusted before I can start working. That’s in part due to my great fear of interruptions, but even more to an excessive proclivity to order and neatness that prevails in my mother’s family. Compulsive Slavic hospitality, and a tedious dutifulness and domesticity, are probably my most time-consuming vices.

Roberto Bolaño

Now that I’m forty-four years old, I’m going to offer some advice on the art of writing short stories.

1. Never approach short stories one at a time. If one approaches short stories one at a time, one can quite honestly be writing the same short story until the day one dies.

2. It is best to write short stories three or five at a time. If one has the energy, write them nine or fifteen at a time.

3. Be careful: the temptation to write short stories two at a time is just as dangerous as attempting to write them one at a time, and, what’s more, it’s essentially like the interplay of lovers’ mirrors, creating a double image that produces melancholy.

4. One must read Horacio Quiroga, Felisberto Hernández, and Jorge Luis Borges. One must read Juan Rulfo and Augusto Monterroso. Any short-story writer who has some appreciation for these authors will never read Camilo José Cela or Francisco Umbral yet will, indeed, read Julio Cortázar and Adolfo Bioy Casares, but in no way Cela or Umbral.

5. I’ll repeat this once more in case it’s still not clear: don’t consider Cela or Umbral, whatsoever.

6. A short-story writer should be brave. It’s a sad fact to acknowledge, but that’s the way it is.

7. Short-story writers customarily brag about having read Petrus Borel. In fact, many short-story writers are notorious for trying to imitate Borel’s writing. What a huge mistake! Instead, they should imitate the way Borel dresses. But the truth is that they hardly know anything about him—or Théophile Gautier or Gérard de Nerval!

8. Let’s come to an agreement: read Petrus Borel, dress like Petrus Borel, but also read Jules Renard and Marcel Schwob. Above all, read Schwob, then move on to Alfonso Reyes and from there go to Borges.

9. The honest truth is that with Edgar Allan Poe, we would all have more than enough good material to read.

10. Give thought to point number 9. Think and reflect on it. You still have time. Think about number 9. To the extent possible, do so on bended knees.

11. One should also read a few other highly recommended books and authors— e.g., Peri hypsous, by the notable Pseudo-Longinus; the sonnets of the unfortunate and brave Philip Sidney, whose biography Lord Brooke wrote; The Spoon River Anthology, by Edgar Lee Masters; Suicidios ejemplares, by Enrique Vila-Matas; and Mientras ellas duermen by Javier Marías.

12. Read these books and also read Anton Chekhov and Raymond Carver, for one of the two of them is the best writer of the twentieth century.

translated from the Spanish by David Draper Clark

"Unwritable Girl" - Gregory Alan Isakov (mp3)

"Fire Escape" - Gregory Alan Isakov (mp3)

"Words" - Gregory Alan Isakov (mp3)

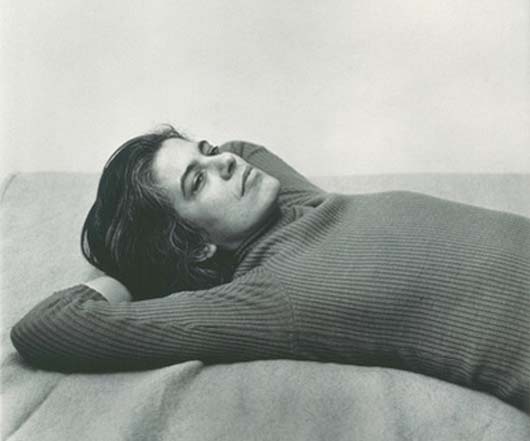

susan sontag

susan sontag

It's Easier To Do Things When Someone Tells You How

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

margaret atwood in cambridge, 1963

margaret atwood in cambridge, 1963