TECHNOLOGY

TECHNOLOGY « In Which We Explain The Parting of the Sensory »

Saturday, August 30, 2008 at 9:10PM

Saturday, August 30, 2008 at 9:10PM

Ways of Peeing

by Tavet Gillson

Visual art and technology are entwined in a tumultuous relationship.

Every so often, a technological breakthrough (linear perspective, the camera obscura, the photograph, the computer) revolutionizes the way the world produces and interprets images. These sorts of transformations are sudden and unequivocal: the new way of seeing swallows up the old visual order, forcing artists to adapt to new techniques and conventions.

Take the word “cat,” for example.

“Cat” means roughly the same thing whether it is handwritten, typewritten or on a webpage. But a painting of a cat is different – it doesn’t look the same as a photograph of a cat, and a film of a cat isn’t much like the other two. The meanings of images are rooted in their construction, whereas the meanings of written words are largely unaffected by their means of transmission.

Technology has the power to reinvent vision, and to retroactively alter established art forms. In the mid nineteenth century, the invention of the photograph caused the rapid, simultaneous development of hyper-realistic panting (with flat, high-contrast space) and its blurry, emotive counterpart, impressionism (filled with exaggerated colors and visually ambiguous forms).

The psychological impact of the Daguerreotype catalyzed two opposing, intensely experimental movements in painting, one in which artists sought to infuse painting with photographic truth; another which rejected the exactness of the mechanical image in favor of a deeper investigation into the tactile qualities of oil pigment.

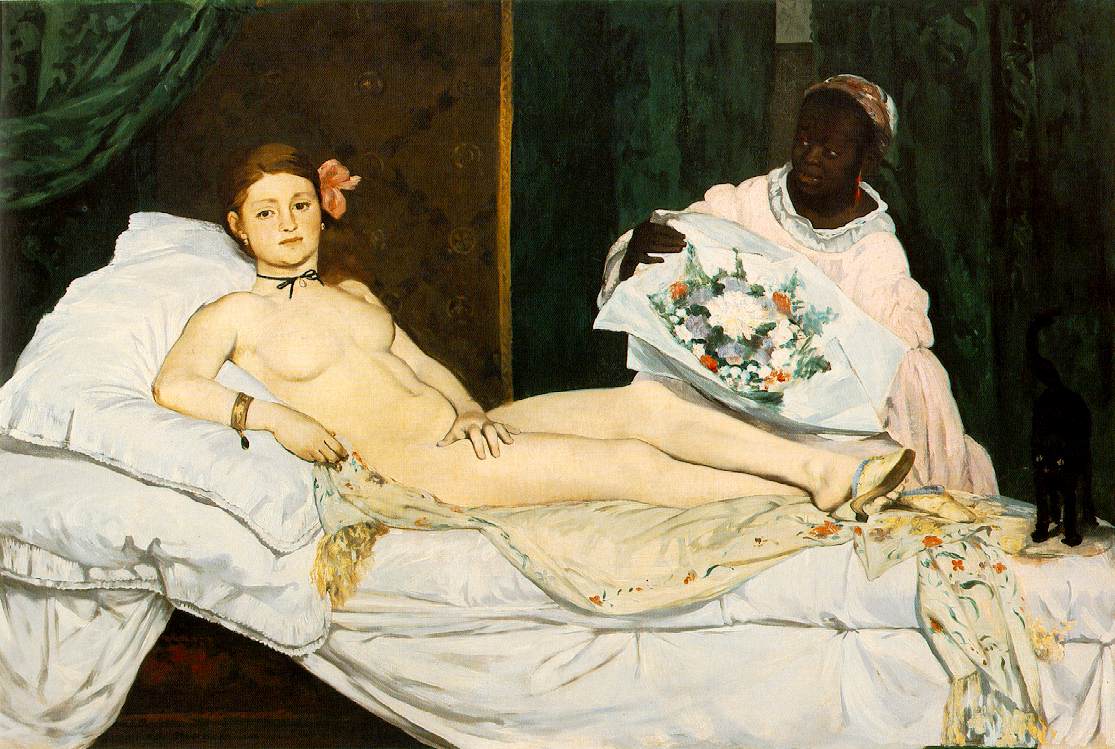

Manet's Olympia

The best uses of technology produce transcendent, uncanny works of art.

In the 1860s, Édouard Manet exploited the party-snapshot voyeurism of high-contrast photography to dramatic effect in his paintings Olympia and Le Déjeuner sur l'herbe.

Fifteen years ago, James Cameron’s Terminator 2 convinced us of the T-1000’s bloodthirsty omnipotence by artfully weaving morphing and reflection mapping (then brand new CG techniques) into a film narrative. We remember these works because they are modern visual dreams, freed from the shackles of traditional perception.

But novelty on its own does not guarantee aesthetic victory. Computers aren’t as paradigm-shattering today as they were ten or fifteen years ago, even though computer technology is always “new” and constantly changing. The day-to-day evolution of technology does not guarantee the aesthetic advancement of art.

A lot of digital artists suffer from short-term memory, and from an attraction to technology rather than to what technology can do for art. Techies aren’t the most culturally shrewd bunch (they love Anime and part their hair down the middle), so most of the digital art on the Internet consists of bizarre, Frazetta/Geiger-influenced illustrations of sci-fi robot women with huge-breasts.

Richard Linklater’s high-tech rotoscoped movies Waking Life and A Scanner Darkly are likewise hindered by a geeky preoccupation with the latest digital toys. Waking Life was praised for its “cutting-edge” use of digital tracing, but the visuals fail to justify a script dripping with pretentious, freshman-year philosophy. In A Scanner Darkly, Linklater goes to great lengths transplanting a generic comic book style onto an already-existing live-action movie.

Less derivative digital art, sometimes called “processing,” is usually too “glitchy” and cold for the average viewer. Shifting grids, abstract 3D shapes and unrecognizably scrambled media clips tend to conjure an atmosphere of disaffected, confused alienation.

Godfrey Reggio’s Naqoyqatsi, one of the more highbrow examples of “digital art,” attempts to make sense of the digital pastiche by cycling through every technologically themed image in existence, no matter how passé or ugly (to the music of Philip Glass, no less). Like a lot of academic art about mass media, Naqoyqatsi falls victim to the schizophrenia it is trying to parse.

Of course there are exceptions – the digital artists Jeremy Blake (who committed suicide in July) and Paul Chan, fuse romantic, mystical imagery with postmodern, high-tech nonlinearity.

Ryan Trecartin’s sprawling experimental film A Family Finds Entertainment uses digital effects and pays homage to postmodern confusion, but maintains a blazing, unified aesthetic throughout.

[youtube=http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8y5AxLiUqC8]

Not surprisingly, Blake, Chan and Trecartin all have educational backgrounds in traditional media.

Jeremy Blake's girlfriend Theresa Duncan's blog. More about them here.

Visual art is about seeing, and technology has the capacity to deepen our understanding of that complex cognitive process. Technology can create and collapse genres. It can transpose the characteristics of one medium onto another and it can breathe new life into old forms (with the aid of software, graphic designers have distilled Warhol and Rosenquist into an even slicker, more ubiquitous mass-media aesthetic).

The images that stick in our brains are the ones that mean something in the context of our visual history. Now that the DIY digital media boom has slowed, we can bring a bit of experience to bear on our judgment of emerging art. The next time you’re blown away by something that looks brand new, don’t forget Manet’s chalk-white picnic nude, or that wonderful T-rex in Jurassic Park.

Tavet Gillson is an MFA candidate in experimental animation at CalArts. You can see more of his work here.

IF TODAY IS THE SAME AS YESTERDAY TOMORROW WILL BE THE SAME AS TODAY

"Moonshiner" - Cat Power (mp3)

"Calculus Man (alternate mix two)" - Modest Mouse (mp3)

"Sample and Hold (Tumbledore edit)" - Neil Young (mp3)

"Dead Lovers' Twisted Heart" - Daniel Johnston (mp3)

"Talk Show Host (live on the BBC)" - Radiohead (mp3)

PREVIOUSLY ON THIS RECORDING

Becca's review of My Kid Could Paint That.

Our love of Tony Romo.

Just the way it pulled apart.

science-corner,

science-corner,  technology

technology

Reader Comments (4)

coool post TAvet!

Awesome!

Have you seen koyanaquatsi? If so, what do you get out of the difference between it and Naqoyqatsi? Just curious. . . .

[...] Give her access to everything. [...]