TV

TV In Which It Was Another Generation

Wednesday, September 9, 2009 at 10:43AM

Wednesday, September 9, 2009 at 10:43AM

After the Cold War, A Long Trek

by ALEX CARNEVALE

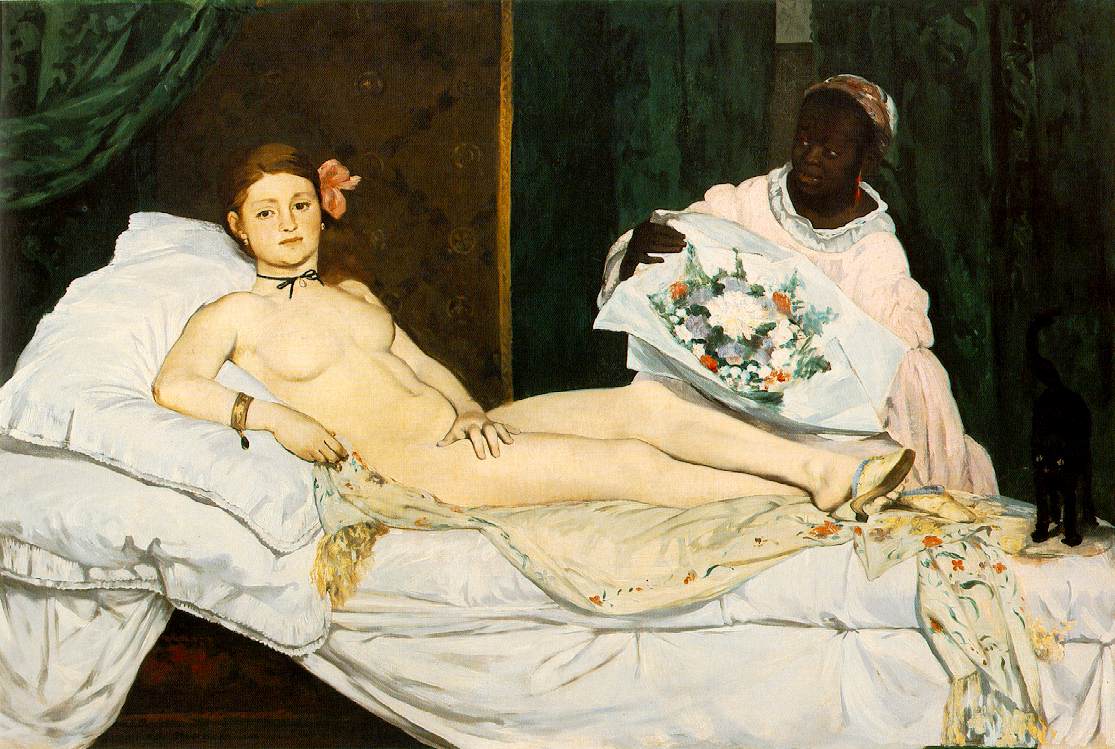

In difficult times we harken back to that which brings us life. The success of America's aims abroad had peaked when we sent the monstrosity known as the Soviet Union packing. The Russia people were beginning would eventually be ruled by Vladimir Putin and the mob. America triumphed in a new age of interstellar peace and happiness. Basically we were these guys.

A lot of us were discovering things about ourselves. The decade of the 1990s would spawn a number of such well-intentioned malcontents, Pauly Shore and Bob Saget to name a few. But the good people were the space people.

The generation before had been marked by the constant monotone of war which found a perilous future in time and space, along with profound moments (like those in the songs of whales) that allowed us to remember what we'd lost. Captain Picard didn't want to blow anyone's face off. He wasn't quick to the gun. He was never even kind of a dick.

The technology that surrounded these peaceful warriors had a relatively negligible effect on its denizens, whose mental processes largely weren't different from 20th century norms. In the character of Data, Star Trek: The Next Generation made an artificial human into humanity and went in depth to prove a machine was, in fact, still a man.

Although men could find whatever drink or food they desired transported to their room, this did not dim their enthusiasm for conquest. Relationships were short-lived, they were as real as they had been before: only more fleeting in their duration. The quickening of life did not quicken the souls of these peacefaring folk.

It can be said that the point of this exercise was to chronicle the fate of man as he adapted himself to the stars, but whatever development would have been made along those lines, Wesley Crusher was a weak-minded syphocant, the symbolic lovechild of a mentally ill Picard. Others failed to adapt as poorly as Wesley — Troi nearly went insane once per season, and Riker always had a little Stephon Marbury in him.

In the Emmy-winning episode "The Inner Light" a probe broadcasting the dying wish of a destroyed civilization attached itself to the handsome Picard. Jean-Luc Picard's dream was of a pretechnological civilization, and he himself adheres to the aims of the age — a promised benign future for him and his family, and obedience to whatever God he chose. In contrast, Data was the far more complex thinker.

Man and machine are destined to become entwined together in bondage, and Star Trek: TNG's plan was to bring that out of hiding, see how the old values held up in a world where you could beam down to a planet full of evil dwarves. This was how we could decide whether technology would overwhelm us entirely.

Among the alien landscape, these figures embodied the older perspective, the West as it was in the world. The Borg became Picard's biggest enemy, the perversity of technological advancement, the hive mind that will abide no other. We were always in greater danger from some casual vicissitude of modernity, like sacrificing whales or changing the timeline. Man's environmental indulgence slowly became the larger symptom of his fate.

Before this period, we imagining ourselves living on the moon, exploring Mars. Then Star Trek came and reminded us that despite this, we were very much alone in the universe.

Is this a future we would want? A lifetime of policing galaxies may be too much to ask from any starfaring race. In the real world, America would of course have her own foreign policy adventures against Communist enemies both real and imagined. The Klingons and the rest disappeared, they were pacified by the entreaties of the Federation. If mankind (America) had to stand atop the galaxies, would he have to also lose his mind and sense of purpose?

Star Trek: TNG was a phenomenon on its debut. After a clumsy first season they soon got to Data and what the rest of it meant by the second season. In the middle seasons the show would abandon the alien-of-the-week concept and expand the purview of the show.

By the seventh season it had been one time travel episode too many and Data had a ho in every city so things were backtracking fast. Picard was looking extremely fatigued, and the lines under Riker's eyes made viewers sad and nostalgic for the last of the exultants.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He tumbls here.

star trek: first contact storyboard

"Snails" — The Format (mp3)

"The Compromise" — The Format (mp3)

"Dead End" — The Format (mp3)

1 Comment |

1 Comment |  1 Reference |

1 Reference |  jonathan riker,

jonathan riker,  star trek,

star trek,  technology,

technology,  the 1990s

the 1990s