BOOKS

BOOKS « In Which Michael Ondaatje Relives Almost Everything »

Thursday, October 13, 2011 at 10:22AM

Thursday, October 13, 2011 at 10:22AM

Knife Wound

by ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS

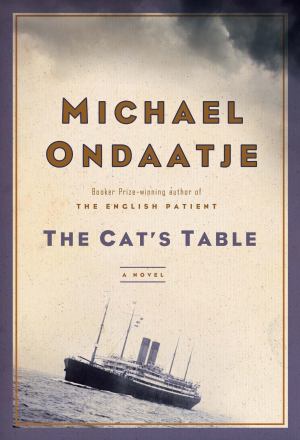

The Cat's Table

by Michael Ondaatje

288 pp

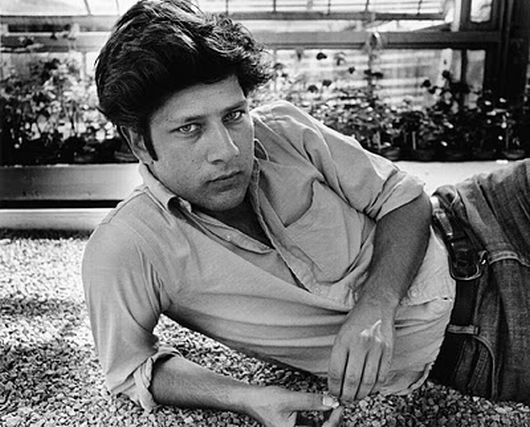

If I ever get Michael Ondaatje alone in a room, I'm going to inspect him for oddly shaped scars.

If I ever get Michael Ondaatje alone in a room, I'm going to inspect him for oddly shaped scars.

Should he have them, I am sure he wears them with pride: here is a man for whom a stabbing is a non-negotiable plot device. These quick, painful but nonlethal acts of violence appear again and again in his work, and always bound up with sex. In his novel Anil's Ghost, a woman takes an avocado knife to her ex's arm; in Divisadero, a girl stabs her father in the back with a shard of glass to prevent him from killing her lover. In Coming Through Slaughter, the stabbing is symbolic — the photographer E.J. Bollocq slashes his own photographs — but its purpose is the same, to get at some primal, anxious connection. "You think of Bellocq wanting to enter the photographs, to leave his trace on the bodies," Ondaatje writes.

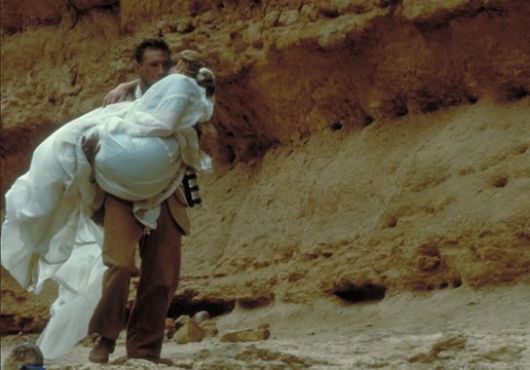

And in The English Patient, violence in the relationship between Katharine and Almásy is apparently so pervasive that a stabbing warrants nothing more than an entry in a catalogue:

A list of wounds.

The various colours of the bruise — bright russet leading to brown. The plate she walked across the room with, flinging its contents aside, and broke across his head, the blood rising into the straw hair. The fork that entered the back of his shoulder, leaving its bite marks the doctor suspected were caused by a fox.

You can imagine the unspoken subtitle for Ondaatje's 1979 book of poems, There's a Trick with a Knife I'm Learning to Do: "Stab you with it."

The enthusiastic reader of Ondaatje, then, might wonder how a crime-of-passion stabbing could possibly work its way into his newest novel, The Cat's Table, released this month. It isn't the sort of novel, on its surface, that should seem to have one: it is the story of an 11 year-old boy, nicknamed Mynah, on a passage from southeast Asia to London aboard a gigantic 1950s ocean liner called the Oronsay. He quickly makes two friends, the impetuous Cassius and the sweet, fragile Ramadhin, and the three set out to learn all they can in the three weeks they are together.

At first, it seems like The Cat's Table should be the novel in which Ondaatje finally leaves the erotic stabbings out. But to think so is to give him both too much credit (he can't resist!) and too little (when he does find a way to push the knife in, so to speak, it's well deserved). But to come back to Ondaatje's own scars: why should I care if he has them? Isn't it unfair to assume that his favorite motif is based in personal experience? Didn't Barthes teach us not to care anyway? Isn't it, you know, fiction?

Yes and no, I think, when it comes to this one. Thankfully, we're not beholden to Barthes anymore, so we can indulge in the delicious speculation that The Cat's Table might be, in part, a memoir. As a boy, Ondaatje took the same journey his protagonist did, from southeast Asia to London. When we flash forward to his protagonist's future, the character lives in Canada just as the author does. They end up at the same school. And Mynah, that echoing bird, is a nickname for Michael.

Ondaatje hasn't made any secret of any of this; there is no clumsy disguise at play here. He makes his intentions clear in an author's note:

Although the novel sometimes uses the colouring and locations of memoir and autobiography, The Cat's Table is fictional — from the captain and crew and all its passengers on the boat down to the narrator. And while there was a ship named the Oronsay (there were in fact several Oronsays), the ship in the novel is an imagined rendering.

It is worth recognizing that this note appears at the end of the novel, though, not the beginning; it's a coda once the story has been told. By this point, we will have learned not to care — because one final way in which the author and his protagonist are similar is that they are both at their best when they observe others. The most beautiful sections of The Cat's Table aren't on the ship at all; they are portraits of the passengers Mynah comes to know, deeply embedded in the past and the future.

"A novel is a mirror walking down a road," Ondaatje wrote in The English Patient. That isn't true for every writer, but it is true for him, and it's what makes the question of whether his claim — that The Cat's Table is not autobiography — is a lie, essentially uninteresting. A mirror can't walk down a road on its own; it has to be held by someone who won't be reflected in it. On second thought, if I ever get Ondaatje alone in a room, I don't want to know a thing about whatever scars he might have.

Ondaatje is not read as widely among literary-fiction snobs as he should be; I know plenty of people who clamored for galleys of The Marriage Plot but neither knew nor cared that Ondaatje, too, had a novel coming out this month. It isn't so hard to figure out why. I think many more people have seen the episode of Seinfeld in which Elaine hates the film version of The English Patient than have actually seen the film, and many more people saw the film than read the novel it was based on.

I actually thought the film was pretty good — Ralph Fiennes still gives me a little frisson, even now, even when he's playing Voldemort — but I do sort of understand. I first read Ondaatje my senior year of high school, when The English Patient was on the syllabus for my English class. We read it near the end of the year, and we had all been dreading it since the beginning. Being warned against something, even by someone you don't trust, makes it hard to embrace that thing. Nothing ruins the pleasure you can get from art like being exposed to someone else's distaste for it. We were all primed to think the novel would be long and slow: because if the movie was, the book must be even worse. In retrospect, maybe we ought to have been more discerning in whose criticism we trusted.

Further, the fans of the movie alienated us. We wondered: How could this book, which had been turned into the kind of movie that moms loved, possibly resonate with us young, sexy teenagers? It did, to an outstanding degree, maybe because our expectations were so low. My classmates liked it more than Beowulf, Macbeth, and infinitely more than Beloved (can't win 'em all). I remember a kid named Travis, talking about the book in study hall, stunned at how moved he was.

In college, too, I knew lots of people who should have been Ondaatje's target audience: young, desperate to prove their literary worth, going through novels almost as fast as cigarette packs. Here, the film adaptation of The English Patient struck another fatal blow. It was an unapologetic prestige film, with a big budget, distributed by Miramax. It won all the Oscars, and it won them in a really good year for independent film. An unnecessary binary opposition fell into place: the Coen brothers are us; Minghella is them. The English Patient — and with it, Ondaatje — became The Man.

It's a shame, because others of Ondaatje's novels really would make excellent films. Anil's Ghost is a beautiful story of loss, hiding inside the kind of grisly mystery that American audiences love to buy tickets for. Any filmmaker who is obsessive about light and interested in a kind of pastoral brutalism — okay, any filmmaker who is Terrence Malick — would do well with Divisadero. But of all his novels, The Cat's Table is the one I would most like to see committed to screen. It is more linear than a lot of the author's work, for one thing. And because the novel's main setting is so rigid — a three-week span, a single ocean liner — the temporal and geographic divergences are easy to swallow.

It would be such a gift to actors, too, to offer them these roles: Mynah, Cassius, Ramadhin, and their companions at the Cat's Table ("the least privileged place," furthest from the Captain's Table, where passengers are "constantly toasting one another's significance"). There's gregarious Mr. Mazappa, who tells the boys dirty jokes and whose presence is mourned after he departs; Mr. Nevil, who dismantles ships; Miss Lasqueti, who keeps dozens of pigeons in a coat with special pockets.

And further on the ship, there is Michael's 17-year-old cousin, Emily, who has her own growing-up to do and of whose own bildungsroman we are allowed glimpses from time to time. There is an Australian girl on roller skates; a villainous captain; a sophisticated thief; a cursed millionaire beset by rabies; a prisoner rumored to have killed a judge. Would that Robert Altman were still alive! One of the novel's best qualities is its constant acknowledgment that every character we meet has his or her own life, with its own complications, and any one of them could be enough to write a book about. It is something Michael and his friends learn: "We came to understand that small but important thing, that our lives could be large with interesting strangers who would pass us without any personal involvement."

Ondaatje himself is interested in film, and there is a lovely scene in the novel in which The Four Feathers is shown onboard the ship. It is a little jarring, too, when the grown-up narrator Michael opens a chapter with the sentence, "Recently I sat in on a master class given by the filmmaker Luc Dardenne." One of the best things that did come out of The English Patient's film adaptation is Ondaatje's relationship with Walter Murch, who edited the film. Ondaatje turned a series of interviews he did with Murch into a book, titled The Conversations. (The title's a little cheeky; Murch was an Oscar nominee for sound editing Francis Ford Coppola's The Conversation.)

Ondaatje directed a couple of films himself, little-seen things in the 1970s, but it is clear in The Conversations that what really fascinates him in film production is editing. It's not surprising; those who love Ondaatje praise the lyrical nature of his writing, and no one is a film's poet more than its editor. As Murch explains in the book: "There's an incredible richness that comes from the unanticipated collisions of things."

Ondaatje is not a subtle writer — those stabbings! — but he is a subtle storyteller, and a complicated one. It's hard to summarize the plot of The Cat's Table because the plot is so sneaky: you don't realize the events of the novel are building toward a climax until you've already reached it. The first two hundred pages of the novel feel simply like a series of stolen moments that aren't necessarily getting at anything larger — and if you are the kind of person who can tolerate that kind of thing, you'll happily float along for the ride, simply because the musings are so beautiful.

Take this example: Mynah falls a little in love with his cousin Emily, as is apt to happen to young boys who have older, beautiful cousins. He writes, "When I left Emily's room… I knew I would always be linked to her, by some underground river or a seam of coal or silver." Or this, in a flash-forward to many years later, when Mynah is reunited by a funeral with a girl with whom he had formative romantic experiences as a teenager: "Our desires were fed by an earlier time, from that very early morning in our youth when she seemed painted by those shifting green branches. We all have an old knot in the heart we wish to loosen and untie."

Even during a harrowing scene, when Mynah and his friend Cassius impulsively (and idiotically) decide to lash themselves to the upper deck during a powerful storm, Ondaatje finds some poetry: "During those few hours when we believed we had given up any chance of our lives, everything coalesced. I was something orderless in a jar, unable to escape what was happening… All I held on to was that I was not alone. Cassius was with me. Now and then our heads turned simultaneously in the lightning and we each saw the blunt, washed-out face of the other."

With language like that, who needs a plot?, I found myself rationalizing, before I figured out what Ondaatje was up to with The Cat's Table. This is where that memoir fallback comes in handy: if Ondaatje is simply recalling what happened to him, then he can be forgiven for the book's events not falling into a neat narrative arc, because when does real life work that way?

The last fifty pages of the novel, though, make clear that there was always a plan for these characters — and because of that, we should probably take Ondaatje at face value when he says he created them. Having finished the novel, as I thought back through its turns, I realized it spirals outward. The adventures Mynah shares with Ramadhin and Cassius start as harmless, typical kids' fare: they swipe extra breakfast from an upper deck, causing the captain to search for a stowaway; they dismantle a cane chair and smoke its twigs; they steal away to spy on the prisoner's midnight walks.

As the novel goes on, though, the stakes get higher, with real repercussions: when Cassius and Mynah lash themselves to the deck during the storm, it nearly kills them; and the dog they pick up during a port stop in Aden really does kill the cursed millionaire. (It bites his throat, which I suppose is about as close to stabbing as a dog can get.) The last scene on the ship gathers nearly all the novel's characters and lets them participate in, or at least bear witness to, a desperate, dramatic event that the author has spent the rest of the text earning. And as a final, perfect stroke, it's an event the narrator himself spends much of his life misunderstanding. He doesn't get the whole truth until years later, when that older cousin Emily volunteers some information that corrects Mynah's version of the history of the Oronsay. I am jealous, at last, of Ondaatje's little Mynah: how wonderful would it be not only to remember your adolescence in such detail, but to be able to fact check it?

For a grown-up reader, one of the most comforting aspects of The Cat's Table is that, although it is at heart a coming-of-age novel, it doesn't present adulthood as a teleological endpoint. Mynah does not arrive in London having learned everything he needs to know, not even about what's just happened in his three weeks aboard the Oronsay, some of which will take decades to unpack. It's more a novel about sailing away from something, I think, than sailing toward something: as Mynah's knowledge of life grows with each new experience aboard the ship, the point of its origin (and the person he was there) becomes more and more unknowable. "A boy goes out the door in the morning and will continue to be busy in the evolving map of his world," Ondaatje writes.

Maybe what The Cat's Table represents to its author is simply a chance to be that kind of busy once again. Near the end of a lengthy Guardian profile published in August, Ondaatje pulls a Robert Frost quotation out of his wallet and reads it aloud to his interviewer: "What we do when we write represents the last of our childhood. We may for that reason practise it somewhat irresponsibly."

Putting aside how charming it is that Ondaatje is the sort of person who carries quotations in his wallet — he figuratively, as well as literally, comes from a place that no longer exists — the self-awareness of this gesture is remarkable. Certainly, whether The Cat's Table is steeped in autobiography or not, it represents the author coming to terms with all the aspects of childhood, including its ending. Ondaatje is 68 years old; he has been an adult for half a century. But there will always be a quality of youth to his work, or more specifically of adolescence, the protracted "last of childhood." This is what I like best about him: the sense that his characters, of all ages, live in a world stuffed with possibility; the desperate immediacy of their actions; their sometimes foolish ardor. A lot of the pleasure of reading Ondaatje comes from visiting this sort of mindset, which most of us experience only in glimpses. Ondaatje, it would seem, is fortunate enough to live in it permanently.

Putting aside how charming it is that Ondaatje is the sort of person who carries quotations in his wallet — he figuratively, as well as literally, comes from a place that no longer exists — the self-awareness of this gesture is remarkable. Certainly, whether The Cat's Table is steeped in autobiography or not, it represents the author coming to terms with all the aspects of childhood, including its ending. Ondaatje is 68 years old; he has been an adult for half a century. But there will always be a quality of youth to his work, or more specifically of adolescence, the protracted "last of childhood." This is what I like best about him: the sense that his characters, of all ages, live in a world stuffed with possibility; the desperate immediacy of their actions; their sometimes foolish ardor. A lot of the pleasure of reading Ondaatje comes from visiting this sort of mindset, which most of us experience only in glimpses. Ondaatje, it would seem, is fortunate enough to live in it permanently.

And as for Frost's permission for the writer to be irresponsible, I think the keyword is "somewhat." When Ondaatje's characters are stabbed, as in all the instances mentioned above, it is almost always in a meaty place — an arm, a shoulder. The act won't kill the victim, or even seriously damage him; it just changes him, adds the mark of a passionately lived life. And while Ondaatje's characters do die sometimes, it is never because their author has been reckless with them.

When reflecting on his own journey from Ceylon to London, Ondaatje muses, "I would not send an 11-year-old child on a three-hour train ride, let alone a three-week boat trip." A cranky reader might point out that the author does exactly this to his own protagonist: he creates the child Mynah, only to loose him on a journey for which he is probably not adequately prepared. But I have learned not to doubt Ondaatje's compassion. I don't think he would have put his protagonist on the boat unless he knew Mynah would emerge safely on the other side, in a different world, a different person.

Alexandria Symonds is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here and she tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about authentrification.

"Pau Hafa Sloppið Undan Punga Myrkursins" - Olafur Arnalds (mp3)

"Wildfires" - Josh Ritter (mp3)

"Kids on the Run" - Tallest Man on Earth (mp3)

Reader Comments