NEW YORK

NEW YORK In Which It Was A Good Party

Thursday, September 27, 2012 at 10:40AM

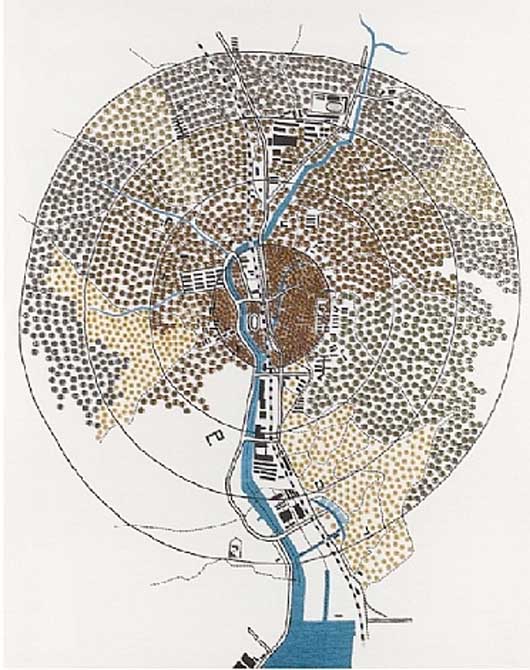

Thursday, September 27, 2012 at 10:40AM  painting by tiffany chung

painting by tiffany chung

What C Said

by ALEXANDRIA SYMONDS

I wake up at the dream’s most vivid moment: the socialite pushes orange-lensed sunglasses down her nose, plucks the tip of a daisy stem from between her teeth, and tells me, in a serious, wistful way: “I think the apocalypse will drive us outdoors.”

I have no idea whether the socialite thinks this, whether she’s ever thought about the apocalypse. She is the chic, waifish great-granddaughter of a famous man who committed suicide. Although we’ve been in the same room plenty of times, we’ve only ever talked long enough for her to tell me some fact she knows is cute enough to survive an editor’s cuts, like: “I demand my own pumpkin pie at family Thanksgivings.”

I don’t know why she’s popped up in my sleep to deliver this message — the apocalypse will drive us outdoors — but it haunts me all day long.

She is right, I decide. At the end of the world, we’ll gather in open areas and tip our chins toward the sky together. It will feel abhorrent and unnatural to be in a building. It will be to miss the point.

What I’d like best is for everyone to be there. Gathered next to the river, maybe, like for Fourth of July fireworks, or on one of the bridges. I have had anxiety in crowds for the last few years, starting I don’t know when and getting I don’t know how much better or worse since. I think it would melt away like butter, if I could be hedged in on every side by the people I have chosen to love and who have chosen to love me.

I think of H., automatically, standing there with me: she is first. I may not be first to her anymore, but that’s okay; that’s why we are going someplace where there is room. In the best version, I am standing on one side of her and M. is on the other, and M.’s closest friends are all standing around him, and their closest friends are all standing around them, in these concentric circles that spiral outward and outward until everyone is accounted for. Because mostly the people who are important to you are the people to whom you are important, and isn’t it lucky that it worked out that way? Doesn’t it make this part easier — this last part?

R. will come here, rather than staying in North Carolina, I hope; so many of her boyfriend’s friends live here, too. X. will be here too, having coaxed her own boyfriend to just put the trip on a fucking credit card, Jesus. (Whether you use your credit cards with abandon in those last few days, or finally get around to paying them off, will say a lot about who you were.) They will come, and he will bring a significant amount of smoked meat.

N. will show up late, running a hand through his hair: “Hey, guys.” His smile will say, Is it good? What’d I miss?

Where are you going after?

J. and C. go without saying. And J.’s mom will be there, and the dog, but my own parents won’t. My mother, determined to survive, will have retreated into her bunker. She and I will have had a desperate fight about it, in the mode our fights always take. She will say it hurts her feelings that I don’t want to come into the bunker; I will interpret this, half-correctly, as a challenge to my independence and insult her, half by mistake.

I will say, grandly, idiotically, “This is the difference between your generation and mine: we have no fight. When someone tells us there’s no hope, we believe it, we adjust to it, we just try to make something tender out of whatever’s left to us.”

She will say she doesn’t understand not even trying. I will repeat, in a tone unintentionally condescending, that if I think there’s no chance of surviving, then it seems pointless to spend the last few hours of Earth crouched in a basement, eating Wheat Thins.

Eventually we will come to an impasse and we will cry and reassure one another that all we want is to see the other one happy, all she wants is me to be safe, all I want is to make her proud, etc.

We will feel pretty good about making some progress.

Later, I’ll ask my father, who privately agrees with me about the bunker but who will be climbing into it with her anyway, why he’s doing it. He will sigh and say he’s so tired: too tired to argue about it. Besides, what would he do with the time if he did?

No amount of notice will be enough to prepare, and that is sort of a sweet thing anyway. The world will end and there will still be a dead bug in the Tupperware on top of the fridge. There will still be a dozen half-finished or barely-started Word documents on your computer—admit it.

As the moment approaches, the verb tense will be complicated, hard to wrangle. I will never have gotten around to buying a new comforter, you will never have gotten around to losing that last ten pounds, she will never have gotten around to breaking his heart, even though all of us knew for ages that they’d have been happier if she did.

We’ll all have the idea that we’ll buy something new to wear, something special for the occasion, but mostly we won’t. The only people who will buy new dresses are the kind of people who buy new dresses for things. (My mom might wear one, in the bunker.)

The rest of us will wear our favorite things, and H. and I will stand in front of her closet and touch all of the soft things in it and debate, because that’s what we do, even if we both sort of know she’ll wear that one red dress and those shoes. She’ll debate heels but ultimately decide that flats are who she is, and isn’t that the idea? Not to be someone else, when it’s your very last chance to be who you are?

We will have gotten dressed in self-parody, in a defiant scramble to find the most representative thing, figure out exactly who we’ve been, just in time to be it. I will be running late and making jokes over my shoulder, and my eyeliner will end up smudged like it always does, and R. will wear a jersey dress and tights and shiny earrings, one of which will dangle close enough to twinkle a little light on the tiny tattoo behind her ear. N. will wear a pastel shirt and that jacket, and D. will wear loafers with brand-new pennies in them, and J. will wear something that doesn’t intellectually make sense but that looks stunning on her. She’ll have gotten it at Century 21, she’ll hasten to tell us.

When we’ve all gotten there, in our favorite dresses, and I brought a lot of wine and H. made brownies and R. has armfuls of bright sweet fruit, it will finally make sense to all of us at once, that the point of the social networks that grew up as we did, that we spent so much time typing and tagging to build, was to prepare us for this moment: everyone, sprawling, together, connected. Bumping shoulders and starting to apologize and exclaiming oh my God, hi! instead.

Someone will remember to bring Lunch Poems.

We will trade compliments knowing that what we’re really saying, over and over, in different words, is: “I’m so glad for the choices you made that built you. I am so grateful I got to know that person.” When I tell A. that I love a kooky and not altogether flattering accessory he’s picked for the occasion, some silk ascot or bright coat, I will be telling A. that I love him.

Everyone will be fresh from their showers, and I will look around at their faces and think that even though it is so deeply unfair that it should happen now, that I don’t get decades more with these people, at least it is happening when we are all so beautiful.

I will, of course, forget my keys. When I realize this is the first and last time it doesn’t matter, my breath will catch in my throat like a tiny bird trapped in a flue, and the only way to release it will be to laugh.

Just as we will be more ourselves that we have ever been, our social ties will be bright and stark and undeniable, too. W. won’t be anywhere nearby when we all assemble, and if he is, it won’t be on purpose, it won’t be for me. When that first tentative flurry of texts goes out, once we know it’s for real —

so what should we do?

where will you be?

— W. won’t text me, and I won’t text A., and A. won’t text the girl, somewhere, who didn’t get a fair shake from him. That’s how things will go, and maybe a lot of us will have deep little aches when it happens; but that’s okay, too, because the thing about a little ache is that it isn’t final, even if the end of the world is. When it happens, we can all still hold onto our beliefs that unlikely things happen all the time, that maybe he’ll call at the last minute.

I will hold onto the idea that I might end up somewhere near M., after all these years, and that he might have something funny to say. I honestly, truly believe there’s no way I won’t find myself next to B., again, without even trying.

I know there is no perfect way to organize people, and a meaningful place to me is not a meaningful place to you, and there will be separations. (It does seem certain that we’ll all flock to bodies of water — to watch the event from two directions at once, falling from the sky and in its own reflection, rushing to meet itself.) But L. will be in her favorite dress on the shore of Lake Michigan, doing the same thing I am doing on the shore of the East River or Hudson, with all the people who have come to matter to her there. O. will be on the banks of the Charles. G. may show up and disappear again, quietly, before anyone notices she’s gone, and cite some mysterious prior engagement when someone sends her a quizzical text.

Lesser H.s and M.s and R.s and E.s in the city will be elsewhere in the crowd or in other crowds entirely. With all of these people we will trade heartfelt text messages, phones lighting up over and over, and all of the crowds will look, from above, from the perspective of whatever’s coming, like a luminescent organism, bigger and more complicated than a pair of eyes can process after one look—even a long one.

Even without L. and O., there will be enough of us that I or you can turn a full circle and see nothing but people I or you love, be pressed in on all sides by them. We will feel safe, because the world, before it ends, will get small again, will be reduced again to how it was when we were first born and the only people we knew were the people directly in our line of vision. Or the world centuries ago, when every door on every house that held someone important to you was within knocking distance, before our lives got geographically complicated and long before anyone ever had the audacity to do something like move to L.A.

We will be giddy at first, but we’ll start to feel calm, more so the closer it gets, passing around baggies of grapes and crackers and drugs and bottles of wine, making jokes, all of us the most ourselves we have ever been. We will be okay about what happens next, because once something so perfect has happened, how can you possibly go on living?

Alexandria Symonds is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in New York. She last wrote in these pages about Friends with Kids. You can find an archive of her writing for This Recording here. She tweets and tumbls.

“Drone On” – Physical Therapy feat. Jamie Krasner (mp3)

“Ritual” – Blood Diamonds (mp3)