FILM

FILM « In Which We Explore Roman Polanski's Soft Spot »

Thursday, September 29, 2011 at 10:19AM

Thursday, September 29, 2011 at 10:19AM This week we look back at the films of Roman Polanski.

Script

by ROMAN POLANSKI

Back in the days when I was at film school — I think it's different today — we made two silent films of two or three minutes each during the first year. In the third year we made a documentary, and in the fourth a fiction film. Through year film we made our diploma project, the length of which was between 300 and 600 metres. Aside from those requirements, we also worked on other films, for example my own short Two Men and a Wardrobe.

Before I made Two Men and a Wardrobe I'd already made The Bike but it was never finished because the lab accidentally sent a reel of the negative to Moscow where the Youth Festival was taking place, and it was never seen again. The film was in color, and I think it would have been quite good. I did make another film in color, When Angels Fall, which was my diploma film.

Although it was never my intention, Two Men and a Wardrobe is rather symbolic. Two men come out of the sea carrying a wardrobe and walk into town. People can't stand the sight of them traipsing around with this thing, especially when they go into cafes or try to get onto a tram. They stick out and because of this provoke hatred wherever they go. I wanted to show the unpleasant things going on in town around the two of them, all these crimes that no one does anything about because everyone's focused on these two strangers. No one says anything to the murderer of the boys who kill the cat, but at the same time they can't tolerate this bizarre trio of two and the wardrobe who end up just walking back into the ocean.

Of course, that's my version. Every audience member will presumably come up with something completely different. But it's a film, not an article in a political journal or newspaper imbued with an ideology or philosophy.

The Fat and the Lean is the story of a man enslaved. The idea is simply that of someone being tormenting and made to endure harsher and harsher suffering, and who is eventually happy to return to his original hardships. It's similar to the story of the man who bangs his head against the wall. When asked why, he explains, "Because it feels so good when I stop."

I don't have any preferences for shooting on location - it depends on the story. I'm inspired by what I find on film sets. With The Fat and the Lean, for example, it was important that the man escaped into a flat landscape because then we can see that the place he's running away from — the town, this oasis — is so far away. The story couldn't take place in a house where all he would have to do is open and close the door.

I need a situation or characters in order to write a screenplay. The most important thing, whether it's cinema or theater, where someone is playing a part (abstract films don't count), is character. The character, even if it's a dog, is always at the center of the story. Dramatic situations are quickly forgotten but characters remain. A good film is always about its characters, whether we're watching Charles Chaplin, James Dean or James Stewart. For a novel, the writer finds an interesting character he wants to describe and only then creates the story around this person.

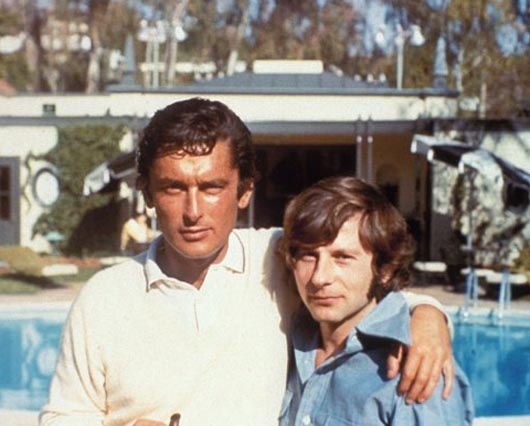

with Robert Evans

with Robert Evans

Apparently some authors — and this applies to painters, too — don't know what they're going to do before they start. They just do it. The results can be astounding, but that's not my way of working. For my short films I always outlined the editing very accurately by making storyboards of each shot, though this never stopped me from changing things at the last minute.

Why not make use of whatever arises on location? I didn't plan each shot with as much care for Knife in the Water because it would have been too time-consuming and I couldn't be bothered. Also because it's just not possible to have control over absolutely everything. The story takes place on a tiny yacht and the situations between the characters are limited. I had to approach it much more in terms of improvisation, and it helped to make only basic sketches of the shots.

Not using direct sound in my short films was never a financial consideration. There are some films where music works better than everyday noises. To include every single sound means a film becomes realistic and concrete, leaving nothing to the imagination. It's not a good idea to include both music and sound effects — you have to choose between them. My short films are not at all realistic so I wanted music in them. I asked a musician whom I've known for a long time to compose something that would express the feelings behind the images. If I'd got rid of the music, I would have added only sound effects and the audience would have wondered why the characters never spoke out loud. But if I'd written dialogue, the story would have become uninteresting. When something is expressed too clearly, it can fall flat.

Cinema isn't like chemistry where you can predict that ten grams of one substance, when combined with five grams of another, will give a particular result. With cinema, I do as I please. When I started at film school everyone had their own theories, but today this is precisely what I mistrust more than anything else. You can't make films with theories, except for things like Last Year in Marienbad which is far too serious for me.

Everything in this life has a comic quality on the surface and a tragic quality underneath. Comic episodes often hide supposedly serious incidents. It's the kind of thing that happens at a funeral or even in a concentration camp. I think that in spite of their great suffering, the prisoners laughed from time to time because of these moments of comedy. There's a lot of literature in this vein.

Personally, I can't stand overly serious films Kaneto Shindo's 1961 film The Naked Island. Besides, they aren't very good films. Life like this just doesn't exist, just as you'd never encounter the kinds of situations you see in Last Year at Marienbad.

I worked as an actor — not as an assistant — for Andrzej Wajda, and I think I've been influenced by him. I worked with Andrzej Munk because we were friends and he asked me, but we had different ideas about cinema. Though I'm more like Wajda and I like his work very much, you can hardly say that I imitate him. My films are quite different from his, though his Ashes and Diamonds is my favorite film. Among Polish talents who are unknown here in France is Wojciech Has who made a film called The Art of Loving.

I'm fairly dismissive of the French nouvelle vague directors because they've made so many third rate films that I can't stand. But what's wonderful is that as a movement, it's completely changed French — and maybe even global — film production. I feel that films like Breathless and all the Francois Truffaut films are works of art.

I'm also very fond of American cinema, directors like Orson Welles and Elia Kazan, and films like Baby Doll, A Face in the Crowd, and Viva Zapata!. I wouldn't say I have a favorite director — I like some of a director's films and not others. I also have a soft spot for American silent comedies which I don't think you could call burlesque.

Repulsion

Repulsion

To my mind, Chaplin's films are very realistic. Look at the walk-on actors — they're so natural. I also like Buster Keaton and The World of Harold Lloyd which has instances of pure genius, like when he climbs like an alpinist over a man who's trying to extract his own tooth. Those are things that you dream and read about as a child. A real man climbing over a man twice his height — it's hilarious! You know, I don't laugh very often at the cinema. If I see something I like, I usually just laugh silently. But that Harold Lloyd film had me rolling in fits of laughter.

I have access to everything I need when I'm filming in Poland. Censorship really isn't an issue there. It's only relevant once a film is finished, but is rarely enforced. In order to make a film, a script has to be shown to a commission whose members meet once or twice a week. Each member receives the script two or three weeks before the meeting where they decide if the film can be made. There are eight production groups in Poland and I'm a member of the Kamera Group. When I have an idea, I submit it to my group leader. If he likes it, he'll ask me to develop it into a script that can be presented to the commission. If the commission rejects it, I'm not able to make the film. The commission deals only with feature films — for shorts it's different because they're less expensive and fewer people are involved. My teacher was responsible for my work and gave his approval for the two or three films I made at the Lodz Film Academy. For Mammals I worked with an independent production group that made shorts and that was able to make certain decision without consulting the authorities.

In Poland I've been accused of "individualistic pessimism." Maybe this has something to do with my personality because I'm a mischievous person. But I can't say that every single critic is against me because most of them have helped a lot. Though critics are important in Poland, it's not like here in France where they can influence audiences and seriously affect a film's reception. At home the authorities support the critics, and a film director — or the group to which he belongs — would encounter serious problems, if for example, his film was labeled as reactionary by one or more official newspapers which are the mouthpieces of the party. But it never happens.

May 1963

with Francesca Annis

with Francesca Annis

From a radio interview with Philip Short:

POLANSKI: When I wrote at the start of my autobiography, "For as far back as I can remember, the line between fantasy and reality has been hopelessly blurred," what I meant was I simply didn't have any concept of where the limits of what's possible are. This helped me in my childhood, my youth and even lately to achieve certain aims and goals that I wouldn't be able to reach without the conviction that everything is possible.

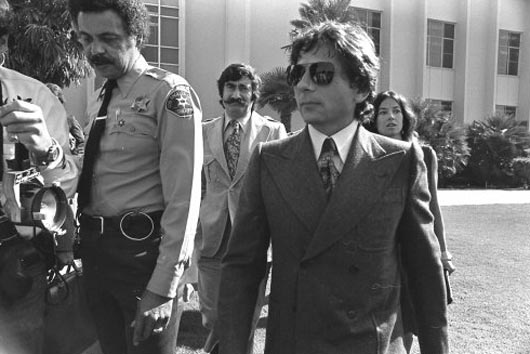

Q: There are people who would say that you brought your troubles on yourself.

POLANSKI: Well, I think that's total nonsense. Of course, to a certain extent you are responsible for your style of life, the life you are leading. You have a choice of the amplitude of the events that happen - the higher you get, the harder you fall. I understand there's a gentleman in England who decided to spend the rest of his life in bed. Not because he's ill, it was just his decision. Such people have very little risk of being run over by a car. So if you see it likes this, then yes, I am responsible, because maybe I live a fuller life than other people.

Q: You came to the West, you went to Hollywood, you married and your wife was murdered. How did you cope when that happened? Quite suddenly, out of the blue, everything that you valued was taken away.

POLANSKI: One doesn't know how one copes with things like that. At the moment one just has to make a decision: to go on living or end it all. I know that in writing this book I had great difficulty in recalling those moments. I had no difficulty at all in remembering all kinds of details from my childhood, but wherever I really suffered grief — in particular, this tragedy — I understand now that my mind just tends to reject certain things, to forget them completely. That probably helps me to live with it afterwards.

1984

"Silver Time Machine" - Death in Vegas (mp3)

"Medication" - Death in Vegas (mp3)

"Your Loft My Acid" - Death in Vegas (mp3)

"Black Hole" - Death in Vegas (mp3)

with Walter Matthau on the set of "Pirates"

with Walter Matthau on the set of "Pirates"

Reader Comments