FILM

FILM « In Which These Are Sisters In Disguise »

Friday, September 30, 2011 at 4:13PM

Friday, September 30, 2011 at 4:13PM This week we look back at the films of Roman Polanski.

The Double Life

by KARINA WOLF

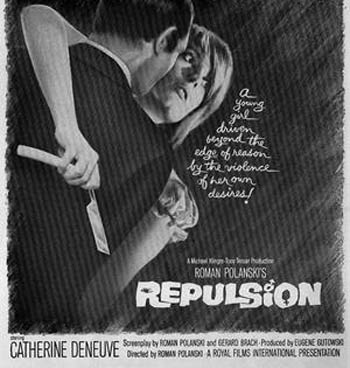

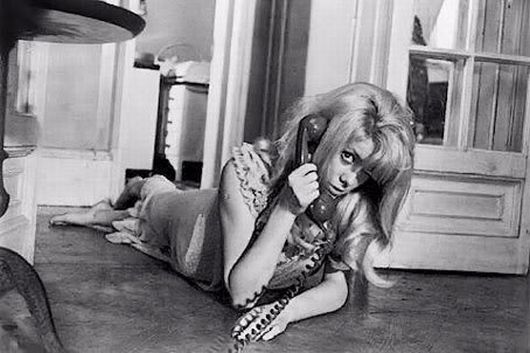

Repulsion

dir. Roman Polanski

105 minutes

Catherine Deneuve followed her sister Françoise Dorléac into filmmaking. Acting was the family business – their father had been a voiceover artist, their mother a doyenne at the Odeon Theatre, and their grandmother an off-stage prompter in Paris. Françoise started in a traditional way, studying at the Conservatoire for a career on the stage.

Catherine was less certain — her first job was for pocket money, playing her sister's twin in Les Collegiennes. They were both beautiful: at times you can see the resemblance, like a double exposed negative of the same person. She took her mother's maiden name, Deneuve, to separate herself professionally. Personally, they were distinct in several ways: Françoise was outgoing, impetuous, impatient. Catherine was inward, shy, hesitant.

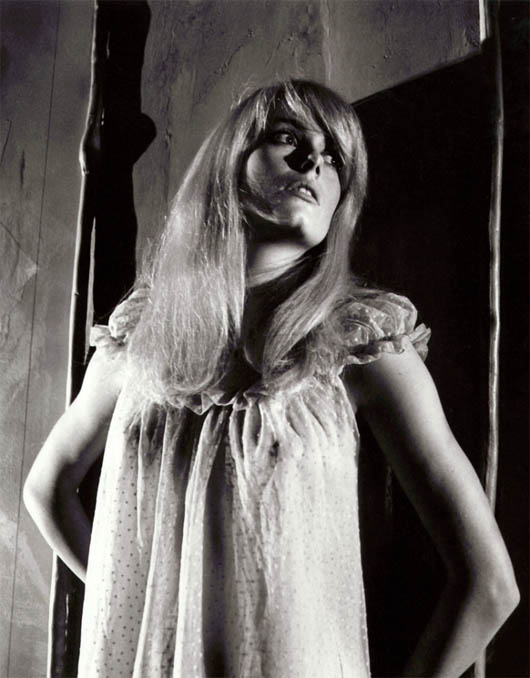

Like many actors who began as children, Catherine was employed for the implications of her form. In even her youngest, most tentative roles, she imparts an unusual melancholy – she is an ingénue only in her Jacques Demy film, the candy-colored The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. From Demy she learned the importance of mise-en-scene, the choreography of a film's aesthetic elements. Perhaps because she was an untrained child actress, she was willing to be led. In part, it is this strange ability and self-knowledge, this volition to be used, that makes Deneuve the perfect heroine for so many directors.

Polanski uses her sadness and inexperience to great effect in Repulsion. The psychological horror film was the director's first in English. All his movies have a hermetic quality – inspired by but unrelated to the living world. This one, about a French girl in London whose mind is eclipsed by madness, was triply removed from reality:

DENEUVE: Three of us were French: Roman, who, despite being Polish, spoke French all the time, Gérard Brach, and me. We really were the Three Musketeers. Everybody else on set was British. Roman knew exactly how to be respected by the crew, he was no pushover. But because we spoke French, we experienced the making of that film a little from the sidelines, in a rather unique atmosphere. We were a core within the team.

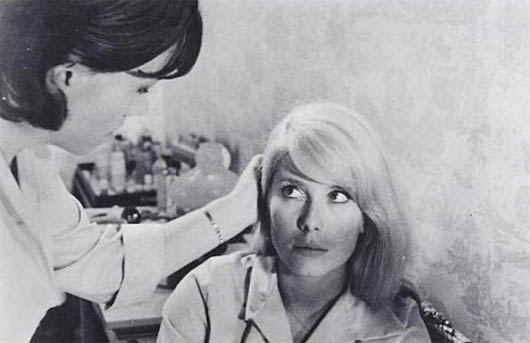

In TV footage from his set, Polanski demonstrates for his star the body language and timing of her character’s reactions quite specifically. He counts out the rhythms of the camera movements; he mimes the intensely fragile delivery of the central character. Deneuve says she is quite pleased with the director: he began his career as a performer, so he understands how to talk to an actor.

Deneuve described the shooting of the fraught film as paradoxically happy. She had a British husband, David Bailey (the inspiration for the lothario photographer in Antonioni’s Blow Up), tony friends (Mick Jagger was the best man at her London wedding) and a sympathetic director who spoke her language (unlike her husband).

There are probably as many ways to direct a movie as there are auteurs. But part of the impulse to produce an effect: I’ve sat with more than one director who has monitored the minute physical reactions of an audience during a screening. The profession is part puppetry and part self-revelation, wherein the director can mold a universe in which the characters and story create a pleasing reality (though pleasing for a director might mean emotional provocation for everyone else).

By having a barely-fluent lead, Polanski's film reinforces the odd idea that sound and dialogue don’t mean much in film. At other times, his sets and cultural referents are those of a person who may have read about a place but never visited it. It’s as if all experience of the outer world is filtered in third-hand. This is fine, of course. Polanski isn’t exactly interested in recreating a documentary world. One can be tempted to say that perhaps it's a documentary of Polanski’s rather unusual psyche.

Repulsion is an experimental film, the kind a college student might attempt, with its fish-eyed closeups of the heroine, who moves from extreme sensitivity to murder and madness. At times, the film is little more than an excuse to look — at length — at one of the world’s most beautiful women. And to watch her suffer, and then take sudden, poisonous revenge on the world that threatens her.

His films as recently as The Ghost Writer and The Pianist make it seem that Polanski’s priorities are unchanged. I was impressed with The Pianist's long passages of silence, when the hero wanders an empty expanse of bombed out Warsaw; his isolation is heightened by the temporary hearing impairment from an explosion. Many of Polanski's characters are cushioned by a similar deprivation. Silence can be restful and protective, or pernicious and toxic.

In 1966's Cul-de-sac, human nature is equivalent to a scorpion’s. Françoise Dorléac's Teresa is unfaithful, slightly spoiled, beautiful and reactive, very much the opposite of Deneuve’s Carol in Repulsion. She’s a real woman who exists in the world — confined in a marriage to an ineffectual but very wealthy member of the British upper class.

The film begins with a couple of criminals whose car stalls on a beach in low tide. One of the pair is gravely wounded. The other, a slab of a man with a boxer’s brow, stumbles off in search of help — he finds Françoise, topless on the beach and embracing a young man. The bully wanders onto the estate — and there we discover Françoise is actually married, and to a different man from the one she was kissing. The husband is George, a bald would-be gentleman who has bought an island castle, it seems, to show off to his friends.

Polanski is terrific at using the camera for a slow, controlled revelation. There's an odd visual pantomime of the exchange of gender roles. Teresa dresses George in her dressing gown, then paints makeup on his face. It’s completely plausible behavior, but as Polanski films it, it’s troubling. What is the relationship between these two? The decoration of George is intimate and playful but irreverent and emasculating. In effect, she dominates him. When the criminal breaks into the house at night to use their telephone, George responds to the intruder while still in female dress. It is utterly impossible for him to regain his footing as the lord of the manor, and the couple are quickly held hostage by the brute who awaits the arrival of Mr. Kastelbach, a Beckettian crime lord whose arrival will signal their delivery to safety. Naturally, Mr. Kastelbach never shows. The criminals don’t survive the siege — but that is unsurprising. The couple is unspared as well, mostly by their own violence.

Polanski assigns intensely angry impulses to his protagonists. When impotent, they have diversely self-harming behaviors. Françoise's character becomes provocative, setting fires between the toes of their sleeping attacker and leveling an empty shotgun at herself while she checks to see the gauges are empty.

Cul-de-sac has a broader arc of action, a more diverse playing field of characters. So why does Repulsion linger in the public imagination?

ARNAUD DESPLECHIN: What I see is the mark of an auteur. Beyond the excellence of your acting, what all your films seem to share, is your gaze, your point of view.

DENEUVE: Yes, you’re right, that’s what it is: a gaze. I think I’ve always leaned toward that. Perhaps because I never went to acting school and never worked with actors. I only ever met them on film sets — I never really had any actor friends, apart from my sister. I was always on the director’s side, or the screenwriter’s. I didn’t choose to, it just happened.”

AD: Like the film you made with Demy, Repulsion demands a closeness between the director and the actor.

CD: Yes, I felt very, very close to Roman. That’s the film I feel I helped make. The producers were used to producing porn. It was a small budget film and for them, nothing of great consequence.

You could argue that Françoise was the better-looking sister, with more symmetrical features and a lither figure. Catherine had prominent eyes, deeply shadowed eyes. Her jaw and nose are less graceful. But why is she the greater star?

In Four Beats To The Bar And No Cheating, Bailey contrasts his first wife and muse Deneuve with his second, supermodel Jean Shrimpton, who he calls a "democratic beauty." Shrimpton was unintimidating and appealing to many. Of course, one could say "undemocratic beauty" is really what we know as "cute."

There's a notable immobility in her expressions — she is an actress who learned her craft while she was doing it, from other actors, and perhaps more importantly, from the directors who saw her as the perfect conspirator. When she's interviewed as a young woman, her inexperience is evident. She purses her lips and flirts with the camera with the assuredness of the beautiful (the smiles, flicking her tongue along her upper lip when she talks). What's wonderful about her as an actress is that she loses all those ticks onscreen.

She is her own center of gravity — and for the first chapter of her career, seemed to work better in films that were overly stylized. Her initial skills as an actress were the guilelessness and remove that accompanied her odd, slightly disturbing beauty. She lets herself go: "Sometimes you have to accept that the image is more powerful than you…"

Karina Wolf is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Manhattan. She tumbls here and twitters here. She last wrote in these pages about the rabbit hole. Her book The Insomniacs is forthcoming from Penguin Putnam.

"Paris Paris" - Malcolm McLaren & Catherine Denueve (mp3)

"Je T'aime...Moi Non Plus" - Malcolm McLaren (mp3)

"Revenge of the Flowers" - Malcolm McLaren & Francoise Hardy (mp3)

"La Main Parisienne" - Malcolm McLaren (mp3)

He's Only One Man: Roman Polanski

Daniel D'Addario on Frantic

Kara VanderBijl on Tess

Alex Carnevale on Bitter Moon

Karina Wolf on Repulsion & Cul-de-sac

Durga Chew-Bose on Rosemary's Baby

Polanski's Script

Reader Comments (1)