FILM

FILM « In Which We Learn To Say Yes To Maybe »

Tuesday, July 10, 2012 at 11:29AM

Tuesday, July 10, 2012 at 11:29AM

A Shaft of Sunlight

by TRACY WAN

Take This Waltz

dir. Sarah Polley

116 minutes

There is always a prospective age, nominated arbitrarily and instinctively, at which we firmly believe we’ll have made it as adults. This number is fluid — it grows with us — but always tucked into a mental pocket. At first, we look forward to it sleeplessly (sixteen, eighteen, twenty-one). Eventually (twenty-five for some, thirty for others, add a decade from that point on), it becomes a threat, a threshold that our failures should not dare to cross. Of course, a fluid number never makes an indelible mark: you never know when you’ve crossed into this realm. We wonder for most of our twenties; somewhere down the line, we get too busy to wonder.

In Sarah Polley’s new film, Take This Waltz, Margot (Michelle Williams) straddles this delimitation, painfully pulled in both directions. Twenty-eight and married for five of those years, she’s an adult by many definitions: employed, settled, committed. She lives in a colorful, tailored-for-two house in Toronto’s Parkdale, with her husband, Lou (a subtle performance by the often burlesque Seth Rogen). He is a cookbook author. He specializes in chicken. Their marriage, at first anyway, seems enviable; they wake up together, eat together, host parties for their loved ones — all evidence of a consonant life. “I love you”s are exchanged, sincerely and frequently, never to fill a conversational void.

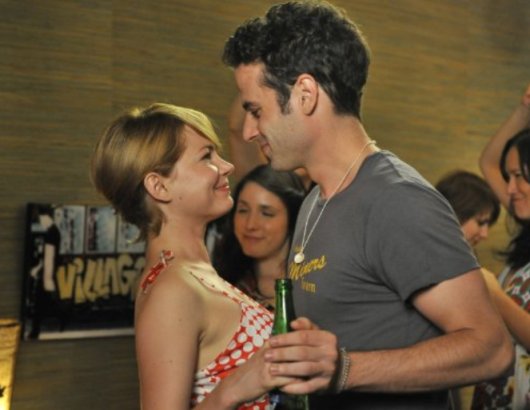

But those who grow into adulthood together can also regress into childlike behaviour together. Their rapport, which seems to have congealed in pre-adolescence, reveals itself through playfights, baby talk and repetitive funny voices. It is colored all the more infantile when Margot’s neighbour, Daniel (Luke Kirby), comes into the picture. To say that they develop a relationship that conflicts with her marriage isn’t a spoiler — that decision opens the film. But it is a delight to observe the minute but visible pains of someone caught in between these dimensions of life, projected by a facial palette as nuanced as Michelle Williams’s.

To much relief, Polley never succumbs to polarities. Daniel does not possess what Lou lacks; the deprivation that Margot experiences in her marriage is not in love or attention. Lou, for all intents and purposes, is a perfect husband — but sometimes perfection is not what one is seeking, merely the change.

Daniel’s attractiveness lies within his otherness. From the moment they meet, he undermines Margot, confronts her, calls her out on her lies. He is acute and frank, aggressive but tender; most importantly, his dynamic with her never allows for childishness. Together, they are unreserved, combative, and it is something that we want Margot to have, if only to see her behave with the sobriety of her age. With Lou, Margot exchanges pet names; with Daniel, an unwavering description of exactly how he’d fuck her (harder than he wanted to). When she tells him that she’s married, he replies: “That’s too bad.” It had only been hours.

One of the many things that Margot confesses to Daniel is her fear of connections: she can’t stand “being in between things.” This film is marked by these liminal spaces, both theoretical and physical, in which decisions are made. On the sidewalks that separate Daniel’s house from Lou’s, Margot and Daniel run into, then plan for, each other. In two instances, Margot sits inside her house, and Lou watches her from their porch — on the first occasion, they make up and kiss through the windowpane; on the second, he tells her to leave, and she does.

“Sometimes I’m walking along the street, and a shaft of sunlight falls in a certain way across the pavement and I just wanna cry. And a second later it’s over. And I decide, because I am an adult, to not succumb to the momentary melancholy.” Sadness can be chosen or it can be denied. In this moment and in many other ways, Margot’s character resonates with me, and with so many of the women that I know. The difference between herself and her niece, she tells Daniel, is that the toddler chooses the melancholy. He isn’t so sure — what if Margot just can’t figure it out? And in the grander scheme of things, she doesn’t. She’s in between, and hates it there.

More than a story about new love and old love’s loss, Take This Waltz explores our ability to make that decision — to not crave a different shade of happiness when life casts its bluer shadows. When Margot leaves Lou for Daniel (again, not a surprise), the film goes through a montage of utopian adult scenarios: they make love in different positions, then with different people. When Margot says “I wuv you,” Daniel does not reciprocate in the same language. She finally cooks for herself. It would be easy to think that she’s crossed the threshold, armed with this new adulthood that her previous life lacked. The new gets old, too.

As it turns out, the most adult realization that we can have is that we will never have it — this idea that happiness is hidden somewhere, in someone, for us to pick from our lives’ branches and call our own. With each new person, we can only learn to love the imperfect yearnings in our old selves. This film’s biggest feat is that it doesn’t start or end anywhere conclusive. It ends in a gap. It decided upon it.

Tracy Wan is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Montreal. She last wrote in these pages about Steve McQueen's Shame. She twitters here. You can find her website here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Golden Cage" - Whitest Boy Alive (mp3)

"Bizarre Love Triangle" - New Order (mp3)

Reader Comments (3)