FILM

FILM In Which We Return To Montana For Horses And The Law

Friday, October 7, 2016 at 10:52AM

Friday, October 7, 2016 at 10:52AM

Survival Gear

by ALEX CARNEVALE

Certain Women

dir. Kelly Reichardt

107 minutes

The setting for the new film by Kelly Reichardt (Night Moves) is rural Montana. The landscape in this place explodes with color along a narrow scale. Darkness is almost complete, but there is never any morning – just a freezing day that plops down without warning. There is no music in Certain Women until about ten minutes before the movie ends, when it seems like the farmhand played by Lily Gladstone is on the verge of potentially displaying an emotion. She never does.

The setting for the new film by Kelly Reichardt (Night Moves) is rural Montana. The landscape in this place explodes with color along a narrow scale. Darkness is almost complete, but there is never any morning – just a freezing day that plops down without warning. There is no music in Certain Women until about ten minutes before the movie ends, when it seems like the farmhand played by Lily Gladstone is on the verge of potentially displaying an emotion. She never does.

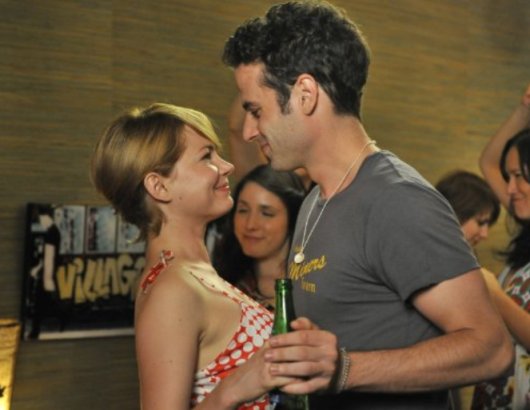

Earlier, Laura Dern has intercourse with Michelle Williams' husband, who is portrayed by James Le Gros. He breaks it off with Dern for reasons we never really understand. It reminds me of when Billy Bob Thornton married Angelina Jolie. "My boyfriend left to do a movie," Dern explained later, "and he never came back." Both Dern and Williams do an incredible job making us forget who they actually are. Reichardt has a true gift for bringing natural performances out of famous actors whose notoriety might otherwise be inclined to overwhelm the diegesis.

Dern is a lawyer with a difficult client (the English actor Jared Harris). Like all three of the short stories Reichardt has adapted here from Maile Meloy, the actual events are very slight. The psychology revolves around a similar type of relationship in which one party can't get away from the other; until she does. Dern achieves this separation by getting her client arrested. He forgives her, even though she does not ask to be forgiven. Reichardt's moral point is that no relationship can exist unless both parties ask for something from the other.

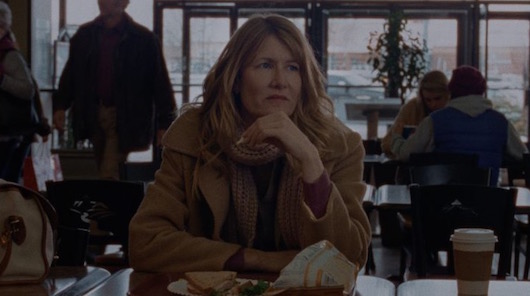

Along those lines Michelle Williams purchases a batch of sandstone from an old man (Rene Auberjonois). He eventually permits her to take it away; she intends to use it in construction of her new house. We see in her conversation with the older man why her husband may have disrespected her by straying from her marriage. Also, she is a smoker with a teenaged daughter. As she enters her late thirties, Williams has become so much fun to watch – here she is a tightly wound ball of anger and persona, expressed as softly as the character can manage.

Visually, Reichardt always knows the correct angle. She is the master of using walls and confined, normal spaces and turning them into subtle psychological aspects in a scene. The clothing that these certain women wear also tells so much of the story. Certain Women begins with Laura Dern in a bra in bed, and as we watch her slowly accumulate enough professional clothing for her job at the law firm, we see how fabric itself is used as protective gear. I mean, Jesus, Kristen Stewart's vest.

Certain Women concludes with its disturbing centerpiece, a story about Lily Gladstone falling in unrequited love with a teacher in a night class (Kristen Stewart). Stewart's lesbian outerwear is truly magnificent, but we get the vague sense that Gladstone is actually the more attractive, complete person as they sit across from each other at the only place in town to get a meal at 10 p.m.

There is one scene where Gladstone's farmhand is brushing her hair in particular where we see the kind of care she could give herself if she only had the inclination or reason to do so. Reichardt falls in love with Gladstone's movements, replaying her routines as she takes care of a beautiful group of horses, circling a pasture to drop hay in the snow. It feels like it has taken her the entire running time to find something she really adores.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.