NEW YORK

NEW YORK « In Which When James Agee Woke He Was Almost Home »

Friday, June 17, 2016 at 10:29AM

Friday, June 17, 2016 at 10:29AM

from Memoir

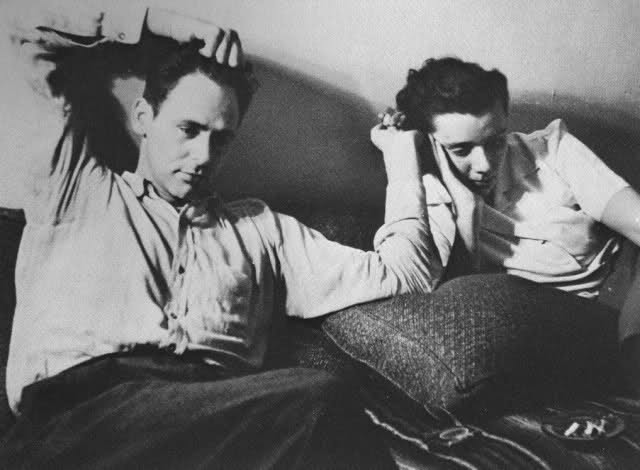

by ROBERT FITZGERALD

Under one strain and another James Agee’s marriage was now breaking up. I remember the summer day in 1937 when at his suggestion we met in Central Park for lunch and the new young woman in her summer dress appeared. It seems to me that there were months of indecisions and revisions and colloquies over the parting with Via, which was yet not to be a parting, etc., which at length would be accomplished as cruelly required by the laws of New York. Laceration could not have been more prolonged.

In the torments of liberty all of Jim’s friends took part. At Old Field Point on the north shore of Long Island, where the Wilder Hobsons had somehow rented a bishop’s boathouse that summers, a number of us attained liberation from the pudor of mixed bathing without bathing suits: a mixed pleasure, to tell the truth.

One occasion in this period that I remember well was a public meeting held in June in Carnegie Hall by a "congress of American Writers," a Popular Front organization, for the Spanish loyalist cause. Jim and I went to his together, and as we took our seats he turned to me and said, "Know one writer you can be sure isn't here? Cummings." MacLeish spoke, very grave. His speech was a prophetic one in which he might very well have quoted, "Ask not for whom the bell tolls: it tolls for thee."

Then he introduced Hemingway. It must have been the only time in his life that Hemingway consented to couple with a lectern, as a matter of fact he only stood besides it and leaned on it with one elbow. Bearish in a dark blue suit, one foot cocked over the other, he gave a running commentary to a movie documentary by Joris Ivens on a Spanish town under the Republic. Jim Agee hoped for the Republic, but I don't think he ever saluted anyone with a raised fist or took up Spanish (my own gesture — belated at that). He had joined battle on another ground.

In October, he put in his second vain application for a Guggenheim Fellowship. His "Plans for Work" (of which he kept a carbon) are printed in this book and will give you an idea of his mood at the time, maverick and omnivorous as a prairie fire, ranging in every direction for What Was the Case and techniques for telling it. As in 1932 he did not fail to indulge in those gratuitous honesties (now about Communism, for instance) that would make it tough for the Guggenheim committee.

I do not know how he lived that winter, or lived through it.

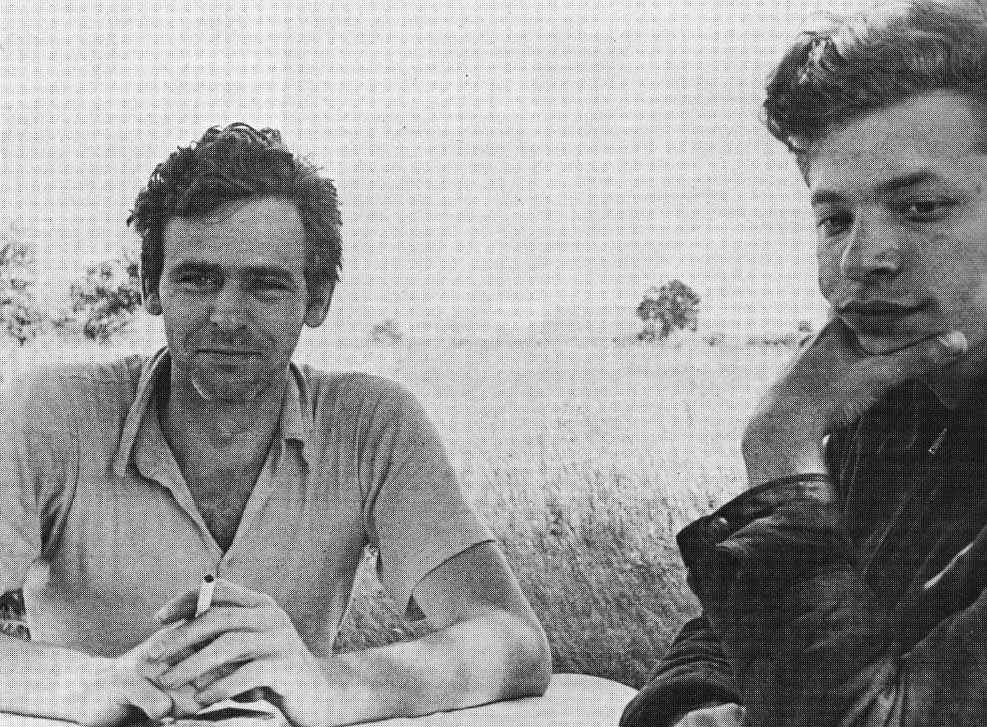

Now, however, till the spring 1938 did he take the Harper's contract and settle down with Alma Mailman, in a small frame house at 27 2nd Street, Frenchtown, New Jersey, to write or rewrite and construct his book. Jim wrote for the ear, wanted criticism from auditors, and read to me, either in Frenchtown or New York, most of the drafts as he got them written. There isn't a word in Let Us Now Praise Famous Men that he — and I and others — did not ponder many times.

Frenchtown was then quiet and deep in the dense countryside, traversable whenever and as far as necessary in an ancient open fliver; they had a goat, God knows how acquired, in the backyard; there was a tennis court in the town. Jim played an obstinate and mighty game, but wild, against my obstinate and smoother one.

He labored all summer and fall, through the Sudeten crisis and the international conferences and the Nazi mass meetings at Nuremberg and elsewhere that sent the strangled shouting of Der Fuhrer and Sieg Heil, Sieg Heil in an ominous rhythmic roar over the radios of the country. He labored into the winter. I have found among his things a journal in which he noted in December 1st that when the rent was paid he would have $12.52 in the world and in the same breath went on with his plans for his wedding to Alma later that month.

In January or February Fortune came to the rescue with an assignment: the section on Brooklyn in an issue to be devoted to New York City. For the rest of the winter and spring they moved to a flat in St. James Place, taking the goat with them. When Wilder Hobson went to see them once he found that the neighborhood kids had chalked on the front steps, "The Man Who Lives Here is a Loony."

After the Brooklyn interlude, the Agees returned to Frenchtown for the summer. Some week before he heard Mr. Chamberlain's weary voice declaring that a state of war existed between his Majesty's Government and Nazi Germany, Jim Agee's manuscript of a book entitled Three Tenant Families was in the hands of publishers. The war began, and the German armored divisions shot up Poland. In the Harper's offices Jim's manuscript must have appeared a doubtful prospect as a rousing topical publishing event. The publishers wanted him to make a few domesticating changes. He would not make the changes.

Harper's then deferred publication; they could live without it. He was broke and in debt, and in the early fall he learned that fatherhood impended for him in the spring. I had just fallen heir to the job of "Books" editor at Time, so we arranged that he should join me and the other reviewer, Calvin Fixx, at writing the weekly book section, and he and Alma fouhnd a flat over on the west side somewhere below at 14th Street.

Now for eight or nine months we worked in the same office several days and/or nights a week. Early that year or maybe late the year before, I can't remember precisely when, the Luce magazines had moved to a new building called the Time & Life Building in Rockefeller Center between 48th and 48th Streets. We had a three-desk office on the twenty-eighth floor with a secretary's cubbyhole. Our secretary, or "checked," was a girl I had known in 1934 when she was Lewis Gannet's secretary on the Herald-Tribune — a crap-shooting hoydenish girl who used to get weekly twenty page letters from a lonely and whimsical young man in a San Francisco YMCA, by the name, then unknown of William Saroyan.

In the years between '34 and '39 Mary had been in South Africa and had come back statelier but still au fond not giving a damn; her father was an Episcopal canon. She kept track of the review books and publication dates and spotted errors in what we wrote. The other reviewer, Fixx, was a Mormon, a decent, luminously inarticulate man engaged in living down some obscure involvement in the Far Left. He knew a great deal about that particular politics and history, now a great subject for "re-evaluation" after the Ribbentrop-Molotov embrace. Each of us read half-a-dozen books a week and wrote reviews or notes — or nothing — according to our estimates of each.

Jim Agee of course added immeasurably to the pleasure of this way of life. If for any reason a book interested him (intentionally or unintentionally on the author's part) he might write for many hours about it, turning in many thousands of words. Some of these long and fascinating reviews would rebound from the managing editor in the form of a paragraph.

We managed nevertheless to hack through that barrier a fairly wide vista on literature in general, including even verse, the despised quarterlies, and scholarship. With light hearts and advice of counsel we review a new edition of the classic Wigmore on Evidence. One week we jammed through a joint review of Henry Miller, for which Jim did Tropic of Cancer and I Tropic of Capricorn, both unpublishable in the United States until twenty years later. Our argument that time was that if Time ought to be written for the Man-in-the-Street (fa favorite thought of the Founder) here were books that would hit him where he lived, if he could get them. In all our efforts we were helped by T.S. Matthews, then a senior editor and later for six years managing editor and friend to Jim Agee.

Not because I idolize Jim or admire every word he ever wrote but again to show his mind at work, this time in that place under those conditions, I will quote the first paragraph of his review of Herbert Gorman's James Joyce and the final paragraphs from his review of The Hamlet by William Faulkner.

The utmost type of heroism, which alone is worthy of the name, must be described, merely, as complete self-faithfulness: as integrity. On this level the life of James Joyce has its place, along with Blake's and Beethoven's, among the supreme examples. It is almost a Bible of what a great artist, an ultimately honest man, is up against...

Whatever their disparities, William Faulkner and Williams Shakespeare share these characteristics:

1) Their abundance of invention and their courage for rhetoric are bottomless.

2) Enough goes on in their heads to furnish a whole shoal of more temperate writers.

3) By fair means or foul, both manage to play not for a specialized but for a broad audience.

In passages incandescent with undeniable genius, there is nevertheless not one sentence without its share of amateurishness, its stain of inexcusable cheapness.

1964

james agee,

james agee,  robert fitzgerald

robert fitzgerald

Reader Comments