ART

ART « In Which She Was Only Beginning To Get Well »

Friday, January 13, 2017 at 11:45AM

Friday, January 13, 2017 at 11:45AM

The Tiny Gospel

by ALEX CARNEVALE

America is going through a period of luxury and unrest bordering nearly on madness.

Alfred Stieglitz had left New York for Vienna in 1881. When he returned in 1890, the Big Apple was a completely changed city. The dark, dangerous metropolis Stieglitz had left grew incandescent in the evening, revealed by the onset of electricity.

+

One aspect of the city became open to him, another closed. His parents wanted young Alfred to marry a spoiled 20 year named Emmeline, called Emmy. Before his wedding, Alfred Stieglitz burned the diary he had kept since he was nine.

Emmy refused to have sex with her new husband, but this was nonce to him. He continued photographing the city and its denizens, and even improved his piano-playing. He gave his new wife the silent treatment. Four years into the marriage, Alfred and Emmy Stieglitz conceived their only child.

Edward Steichen's photograph of Kitty and Alfred Stieglitz

Edward Steichen's photograph of Kitty and Alfred Stieglitz

To commemorate the occasion, the family moved into a new apartment on Madison and 84th. Their daughter Kitty quickly became the center of their conflict, with Stieglitz insisting on photographing the girl almost every second of her life.

Emmy and Alfred were now on speaking terms, but it never got much better than that. As Kitty grew older and remained under the influence of her mother, daughter and father too liked each other less and less. Stieglitz had little time for his family — spreading the tiny gospel that was still photography occupied most of his waking hours. "I would rather be a first class photographer in a community of first class photographers," he pronounced, "than the greatest photographer in a community of non-entities."

+

Kitty graduated from Smith with honors in 1921. She had written her father many letters during her senior year at that Massachusetts college, bonding with him for the first time in her life with her mother in absentia. Since her parents were not speaking again, Alfred could not attend her commencement, but the two grew closer in the years that followed her marriage to a Boston salesman named Milton Stewart.

In June of 1923 Alfred became a grandfather when Kitty gave birth to a son. Severe bouts of postpartum depression dominated Kitty's days. She alternated lashing out at her father for his neglect of her with expressions of closeness. "I certainly failed in so many ways in spite of all my endeavours to protect and help her prepare herself for life," Stieglitz wrote. "I realize with every new day what a child I have been & still am — absurdly so. It sometimes disgusts me with myself."

O'Keeffe and Stieglitz much later, in 1944

O'Keeffe and Stieglitz much later, in 1944

This experience completely convinced Alfred that having a baby with his girlfriend, an artist named Georgia O'Keeffe, was a terrible idea. He continued affairs with other women as well, and he did not want babies with them either. He wrote romantic letters to the wife of his friend Paul Strand, although a relationship with Rebecca Strand would only ever be consummated by Georgia. O'Keeffe was annoyed by Alfred's behavior, rebelling against it whenever she could, but she did tolerate it.

"Stieglitz wants his own way of living," Rebecca Strand told her husband Paul, "and his passion for trying to make other people see it in the face of their own inherent qualities really gets things into such a state of pressure that you sometimes feeling as though you were suffocating." Meanwhile, Kitty's condition had put her suddenly doting father in a weakened state. He made peace with Emmy and together they admitted Kitty into a gorgeous sanitarium in upstate New York.

+

Alfred Stieglitz was suddenly 60 and one of the world's most celebrated photographers. Kidney stones made his nights restless. He passed the time by reading Ulysses. The divorce from Emmy was final. The following summer his daughter was discharged from the hospital to a summer house at Sagamore Beach. He proposed to Georgia; she declined.

By the fall Kitty had been returned to the sanitarium. Her doctor came to Alfred with a proposal. If he married O'Keeffe, they suggested, Kitty might come to a peace of mind that would aid her recovery. In light of these circumstances, Georgia accepted her boyfriend's proposal after considerable pressure was exerted.

Kitty Stieglitz photographed by her father with her uncle Joseph

Kitty Stieglitz photographed by her father with her uncle Joseph

The hasty marriage would change nothing, however, and Kitty's behavior was that of an indolent teen. She never left the care of doctors, spending the next fifty years trying to get well before her death. Kitty never permitted her father to visit, but her mother Emmy came every single week.

+

"Marriage, if it is real must be based on a wish that each person attain his potentiality, be the thing he might be, as a tree bears its fruit - at the time realizing responsibility to the other party," Stieglitz explained to himself. He was impressively dedicated, even in old age, to thinking of very good reasons why he could not be a faithful husband.

Georgia's health problems complicated their new union, restricting her to bed rest. She was only just beginning to get well when Stieglitz met 21-year old Dorothy Norman. The girl who incessantly hung around Alfred's gallery, asking question after question, was married to the son of the founder of Sears. Edward Norman was a deeply disturbed person who was mentally, physically and sexually abusive to his wife.

Dorothy Norman

Dorothy Norman

Stieglitz initially tried to put Dorothy's at an arm's length. By the time he really got to know her, she was pregnant with her first child, a daughter. Like Kitty, Dorothy was a Smith graduate. Georgia noticed her husband's admiration of the pregnant woman, and it upset her greatly. To appease O'Keeffe, Stieglitz tried to confine his expressions of love to secret letters. "I want to incorporate knowing you into my life," Dorothy wrote back, and in order to position herself as closely as possible to the photographer, commenced work on an article about Alfred that would become a book.

Georgia was more and more skeptical of Alfred's protestations that the friendship was not intimate. In her own interview with Dorothy, she found the college graduate annoying, pretentious and transparent. When Dorothy talked with Alfred at the gallery, he told her to sit far from him, "out of danger."

Into his life at this time came Lady Chatterly's Lover, his new favorite book.

Into his life at this time came Lady Chatterly's Lover, his new favorite book.

When Georgia went off to a retreat, Stieglitz finally consummated the relationship with his young admirer. His descriptions of that moment are nauseating at best: "It was as I have never dreamed a kiss could be." He wrote, "We are are one - Every day proves it more and more to be true. Dorothy, do you have any idea how much IWY." The innovative use of acronyms made the tryst appear more than it really was: at first, the couple only kept things above the belt.

This consummation pushed Alfred in the other direction. Georgia was happiest in New Mexico, and Stieglitz endlessly complained about the time she spent there away from him. She felt his pull — "It is always such a struggle for me to leave him" — but New York was not her favorite place. "I think I would never have minded Stieglitz being anything he happened to be," she told a friend, "if he hadn't kept me so persistently off my track."

Alfred's photograph of Dorothy Norman from behind

Alfred's photograph of Dorothy Norman from behind

Even though Alfred thought nothing of cheating on his wife, he flew into a fury whenever he suspected that she might be unfaithful. The balance of their relationship was changing, however, as Stieglitz was increasingly financially dependent on his wife's flourishing artistic career. He was determined to improve his marriage.

Stieglitz still saw much of Dorothy, who had given birth to a second child. He photographed Dorothy Norman for the first time in 1930, when she was 25 years old. Alfred bought Dorothy a camera, and told her that he loved her. Each saw the relationship as a supplement to their marriage, and sought nothing more from one another. A friend wrote to Alfred that talking to Dorothy was like "talking to a mirror in which one didn't see oneself but someone else. She presents no problem, no burden or personality to be dealt with. One can be with her and at the same time alone with oneself."

+

"He was perhaps the most impressive person I have ever known," Dorothy wrote later. "Yet the greatness of what he expresses was in terms of how people must be non-possessive." Alfred Stieglitz demonstrated this principle by comparing his wife and his young girlfriend in a 1932 exhibition that was the talk of the art community.

Their professional ties were solid as well. Dorothy involved herself in Alfred's fundraising efforts at his request, for a gallery that she would run in his name. This closeness rankled Georgia even more, and she sunk into a depression partly brought on by a friend of Alfred's suggesting that she befriend Dorothy.

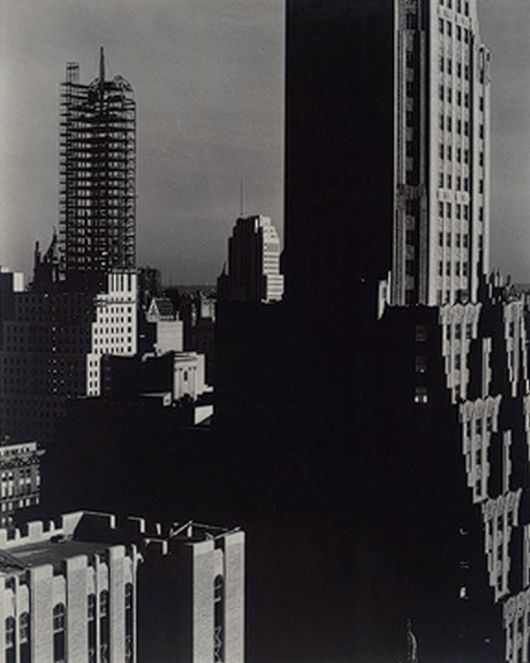

Stieglitz's self-portrait, 1890

Stieglitz's self-portrait, 1890

When Dorothy could not find a publisher for her manuscript of poems, Stieglitz demanded he publish them. This final insult pushed Georgia into the arms of the poet Jean Toomer, who she invited to stay with her on Long Island.

In the spring of 1936, Elizabeth Arden asked Georgia to paint a massive mural in her salon. More flush with cash than she had ever been, Georgia rented a penthouse on 1st Avenue to work on it, a cold, drafty, beautiful workspace. There Alfred suffered his first heart attack, ending his photographic career.

Alfred was now 74 years old. In his feebleness, the arrangement with Dorothy could be nothing more than close friendship. The affair dissipated without ever having a formal break. Both had provided something the other needed, is how Dorothy saw things, something essential and something clandestine. "There was a constant grinding like the ocean," O'Keeffe wrote of her husband. "It was as if something hot, dark, and destructive was hitched to the highest, brightest star. He was either loved or hated — there wasn't much in between."

In the days that followed Stieglitz's small funeral, Georgia called up Dorothy Norman. She told Dorothy to clear all her stuff from the gallery, commenting that she found Dorothy's relationship with her husband "absolutely disgusting." After Alfred's death, Georgia O'Keeffe lived forty more years.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.

Reader Comments