Past the Last Locust Tree

I am learning something myself — I don’t know exactly what it is — but if I did — if I could put it clearly into form it would cure you

It is easy to fall in love with the paintings of Georgia Totto O'Keeffe, but it is even easier to embrace her private correspondence. She was just the best. Her psychological insights were astonishing. She knew how to say — everything, knew how to spin an event into something more important than it was, less important than it was, put it outside of herself, bury it within. In her lifetime, she became as well known for her personality as for her paintings which so captivated and divided the art world upon their first appearance in the 1920s. O'Keeffe died in 1986 at the eight of 98.

She met her friend Anita Pollitzer at Columbia University. Anita called her "Pat" and would eventually introduce her to future husband Alfred Stieglitz.

To Anita Pollitzer

Canyon, Texas

11 September 1916

Tonight I walked into the sunset — to mail some letters — the whole sky — and there is so much of it out here — was just blazing — and grey blue clouds were rioting all through the hotness of it — and the ugly little buildings and windmills looked great against it.

But some way or other I didn't seem to like the redness much so after I mailed the letters I walked home — and kept on walking —

The Eastern sky was all grey blue — bunches of clouds — different kinds of clouds — sticking around everywhere and the whole thing — lit up — first in one place — then in another with flashes of lightning — sometimes just sheet lightning — and sometimes sheet lightning with a sharp bright zigzag flashing across it —.

I walked out past the last house — past the last locust tree — and sat on the fence for a long time — looking — just looking at the lightning — you see there was nothing but sky and flat prairie land — land that seems more like the ocean than anything else I know — There was a wonderful moon —

Well I just sat there and had a great time all by myself — Not even many night noises — just the wind —

I wondered what you are doing —

It is absurd the way I love this country — Then when I came back — it was funny — roads just shoot across blocks anywhere — all the houses looked alike — and I almost got lost — I had to laugh at myself — I couldnt tell which house was home —

I am loving the plains more than ever it seems — and the SKY — Anita you have never seen SKY — it is wonderful —

Pat.

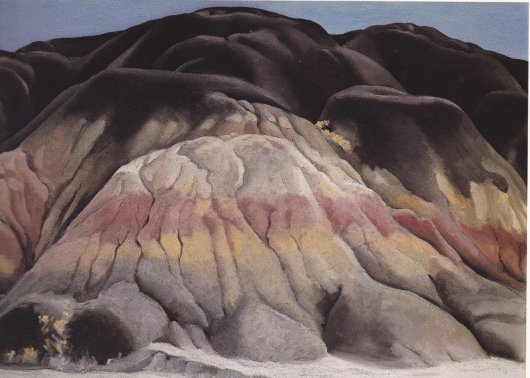

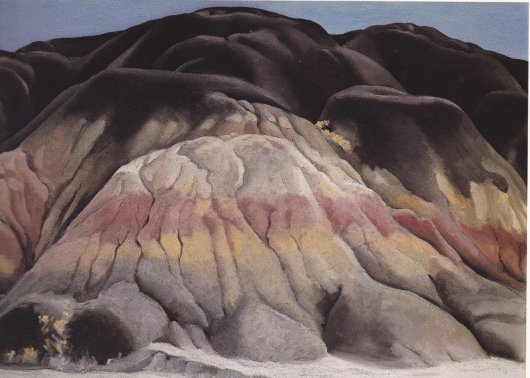

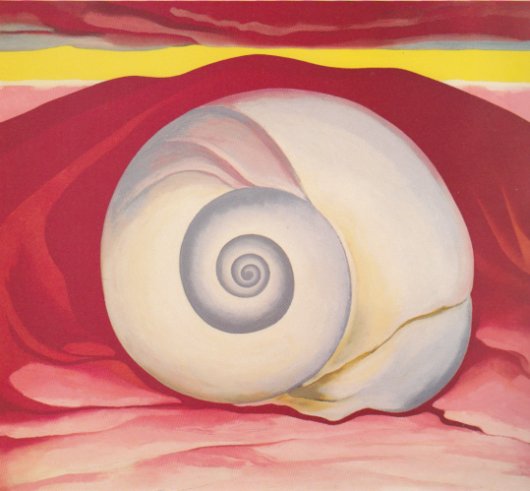

grey hills, 1942

grey hills, 1942

O'Keeffe and the American writer Sherwood Anderson both shared a Midwestern background. He was a close friend of Stieglitz and it was his encounter with Georgia's work that inspired him to paint for the first time in his life.

To Sherwood Anderson

Lake George

1 August 1923

Dear Sherwood Anderson:

This morning I saw an envelope on the table Stieglitz addressed to you — Ive wanted so often to write you — two things in particular to tell you — but I do not write — I do not write to anyone — maybe I do not like telling myself to people — and writing means that.

First I wanted to tell you — way back in the winter that I liked your "Many Marriages" — and that what others have said about it amused me much — I realize when I hear others speak of it that I do not seem to read the way they do — I seem to — like — or discard — for no particular reason excepting that it is inevitable at the moment. — At the time I read it I saw no particular reason why I should write you that I liked it — because I do not consider my liking — or disliking of any particular consequence to anyone but myself — And knowing you were trying to work I felt that opinions on what was past for you would probably be like just so much rubbish — in your way for the clear thing ahead — And when I think of you — I think of you rather often — it is always with the wish — a real wish — that the work is going well — that nothing interferes —

I think of you often because the few times you came to us were fine — like fine days in the mountains — fine to remember — clear sparkling and lots of air — fine air

And the letters you have written Stieglitz the last few months have helped much over difficult days — The spring has been terrible and when we got here he was just a little heap of misery — sleepless — with eyes — ears — nose — arm — feet — ankles — intestines — all taking their turn at deviling him — one after the other — and it is only the last few days that he is beginning to be himself again — I had almost given up hope — It was rather difficult — in a way he is amazingly tough but at the same time is the most sensitive thing I have ever seen — The winter had been very hard on him — The nerves seemed tied up so tight that they wouldnt unwind — So you can see why I appreciated your letters — maybe more than he did — because of what they gave him — I dont remember now what you wrote — I only remember that they made me feel that you feel something of what I know he is — that it means much to you in your life — adds much to your life — and a real love for him seemed to have grown from it

And in his misery he was very sad — and I guess I had grown pretty sad and forlorn feeling too — so your voice was kind to hear out of faraway and I want to tell you that it meant much — Thanks

Sincerely

Georgia O'Keeffe

I can only write you this now because things are better.

The artist Russell Vernon Hunter had seen Georgia's painting of a cockscomb and included it in a letter to her.

to Russell Vernon Hunter

New York

Spring 1932

My dear Vernon Hunter

Your letter gives me such a vivid picture of some thing I love in space — love almost as passionately as I can love a person — that I am almost tempted to pack my little bag and go — but I will not go to it right this morning — No matter how much I love it — There is some thing in me that must finish jobs once started — when I can —.

So I am here — and what you write of me is there

The cockscomb is here too — I put it in much cold water and it came to life from a kind of flatness it had in the box when I opened it — tho it was very beautiful as it lay in the box a bit wilted when I opened it —. I love it — Thank you.

I must confess to you — that I even have the desire to go into old Mexico — that I would have gone — undoubtedly — if it were only myself that I considered — You are wise — so wise — in staying in your own country that you know and love — I am divided between my man and a life with him — and some thing of the outdoors — of your world — that is in my blood — and that I know I will never get rid of — I have to get along with my divided self the best way I can —.

So give my greetings to the sun and the sky — and the wind — and the dry never ending land

—Sincerely

Georgia O'Keeffe

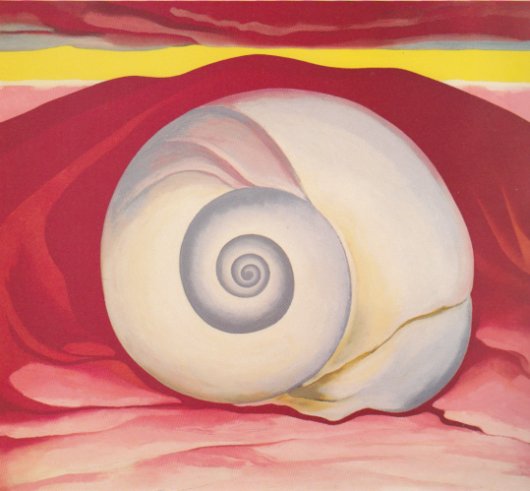

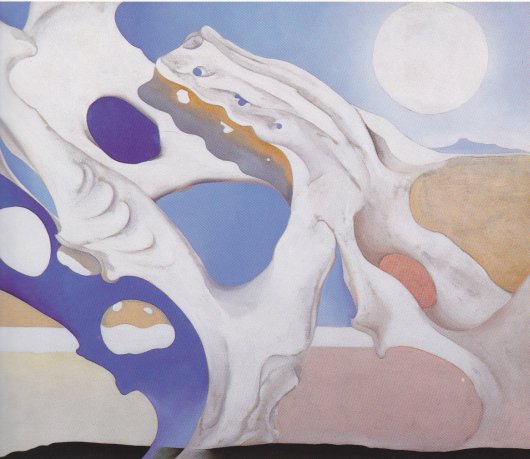

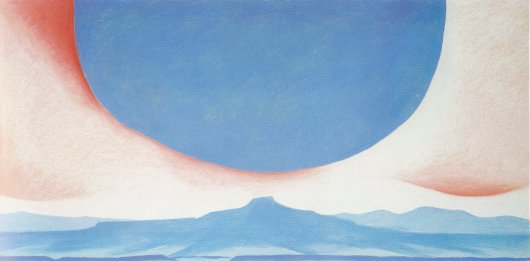

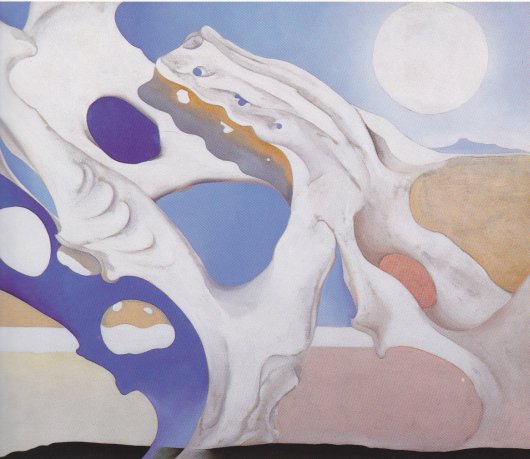

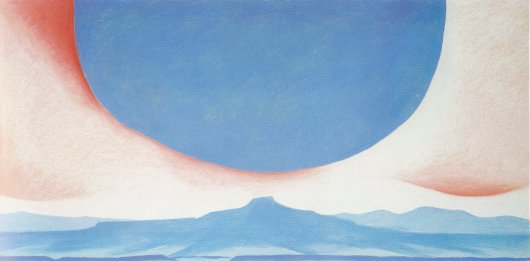

pelvis with shadows and the moon, 1945

pelvis with shadows and the moon, 1945

Georgia's letters to the celebrated African-American poet Jean Toomer are among her most affecting. Her relationship with Toomer was intense, emotional, and possibly sexual. Her descriptions of the cats at Stieglitz's family home at Lake George constitute one of many highlights.

to Jean Toomer

Lake George

10 January 1934

I waked this morning with a dream about you just disappearing — As I seemed to be waking you were leaning over me as you sat on the side of my bed the way you did the night I went to sleep and slept all evening in the dining room — I was warm and just rousing myself with the feeling of you bending over me — when someone came for you — I wasn't quite awake yet — seemed to be in my room upstairs — doors opening and closing in the hall and to the bathroom — whispers — a womans slight laugh — a space of time — then I seemed to wake and realize you had gone out and that the noises I had heard in my half sleep undoubtedly meant that you had been in bed with her — and in my half sleep it seemed that she had come for you as tho it was her right — I was neither surprised nor hurt that you were gone or that I heard you with her

And you will laugh when I tell you who the woman was — It is so funny — it was Dorothy Kreymborg

And I waked to my room here — down stairs with a sharp consciousness of the difference between us

The center of you seems to me to be built with your mind — clear — beautiful — relentless — with a deep warm humanness that I think I can see and understand but have not — so maybe I neither see nor understand even tho I think I do — I understand enough to feel I do not wish to touch it unless I can accept it completely because it is so humanly beautiful and beyond me at the moment I dread touching it in any way but with complete acceptance. My center does not come from my mind — it feels in me like a plot of warm moist well tilled earth with the sun shining hot on it — nothing with a spark of possibility of growth seems seeded in it at the moment —

It seems I would rather feel it starkly empty than let anything be planted that can not be tended to the fullest possibility of its growth and what that means I do not know

but I do know that the demands of my plot of earth are relentless if anything is to grow in it — worthy of its quality

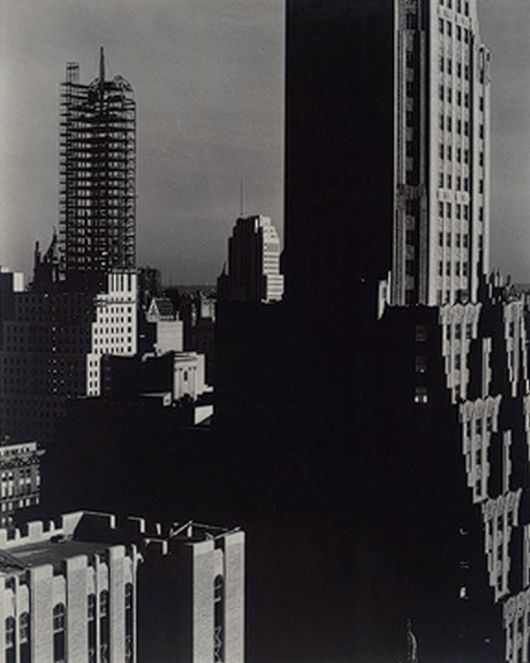

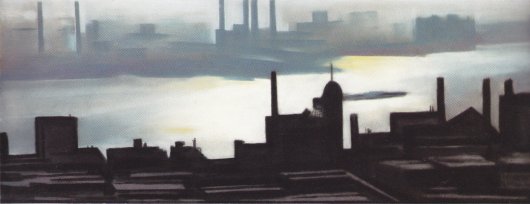

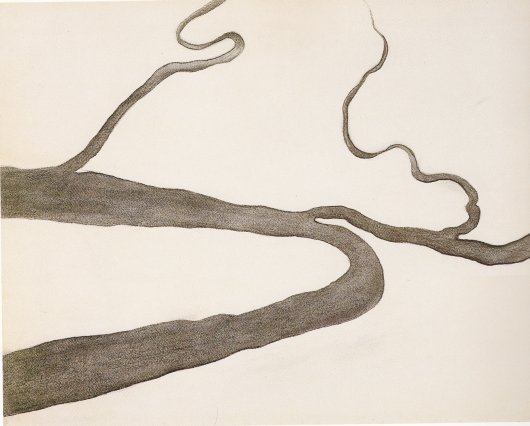

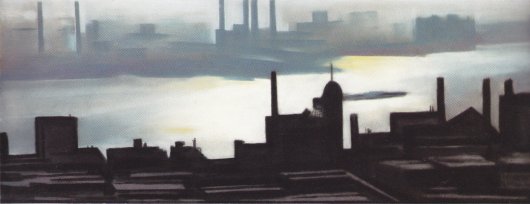

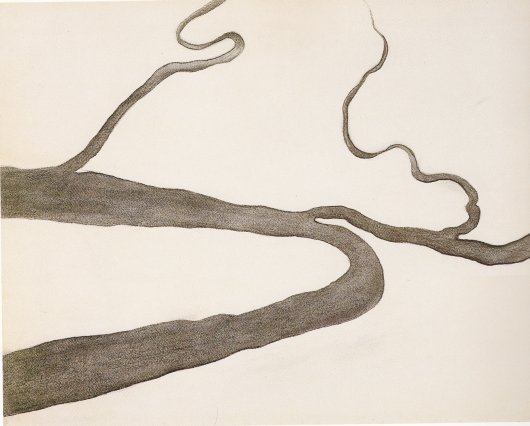

east river, new york, no. 2 , 1927

east river, new york, no. 2 , 1927

Maybe the quality that we have in common is relentlessness — maybe the thing that attracts me to you separates me from you — a kind of beauty that circumstance has developed in you — and that I have not felt the need of till now. I can not reach it in a minute

If the past year or two or three has taught me anything it is that my plot of earth must be tended with absurd care — By myself first — and if second by someone else it must be with absolute trust — their thinking carefully and knowing what they do — It seems it would be very difficult for me to live if it were wrecked again just now —

The morning you left I only told you half of my difficulties of the night before. We can not really meet without a real battle with one another and each one within the self

if I see at all

You have other things to think of now — this asks nothing of you.

It is simply as I see — I write it — though I think I have said most of it —

My beautiful white Kitten Cat is in a bad way for three days — she seems to have a distressing need for a grown real male — and these two little Kittens seem quite puzzled and frequently quite excited — and they are all running me wild — I feel like digging a hole in the back yard and burying the whole outfit

I never saw such a performance before — and right at this moment I dont need it — troubles enough with myself —

I do have to laugh when I think of your possible remarks if it had happened when you were here

I like you much.

I like knowing the feel of your maleness

and your laugh —

to Jean Toomer

On the boat from New York to Bermuda

5 March 1934

Just a little I must write you from the boat before I start into another way of living.

It has been a warm — soft — smooth — sparkling day — Sun that I seemed to have forgotten could be warm — I felt petted all over — lying out there on the deck — alone — looking at the water — It seems another world — I am glad to be moving into it — away and away from everyone and everything that seems connected with my life — everything except myself of course — it is something of a trial to take that along —

The days in the city were very good for me I think — tho I did not enjoy them particularly. I had to go shopping as I had very little to wear and the struggles with garments of various kinds — shopgirls — taxis and what not was good I think — It got me back very much into my old way of going about and doing things so that each day it seemed to tire me less

As for my connections with people — I feel more or less like a reed blown about by the winds of my habits — my affections — the things that I am — moving it seems — more and more toward a kind of aloneness — not because I wish it so but because there seems no other way. The days with A. were very dear to me in a way — It was very difficult to leave him but I knew I could not stay —

east river from the shelton, 1928

east river from the shelton, 1928

The city was cold and windy — snow as I never saw it there — the harbor all floating ice

My old sense of reality seems displaced and I cannot quite anchor a new one — What you write me of your eye and your cold bothers me — particularly since I have not heard again — I imagine you got a cold and got sick just because things seemed too difficult for you — or I am wrong.

Anyway it bothers me — particularly as I seem to be treating myself very well — taking myself to the sun

It all makes everything seem so awry and fantastic

Someone skidded into my parked car before I left Lake George and did $35.00 worth of damage to the side of it — Luckily I was insured

I hope you are better

You must know that my coming out here to these toy islands on the glassy green blue sea is only an evasion — I do not look forward to it — do not like it that I come for any such reason but that is the way it is

I will write you of the life when I get to it — The circumstances are bit odd to say the least

In the meantime I hope you are better and busy at something —

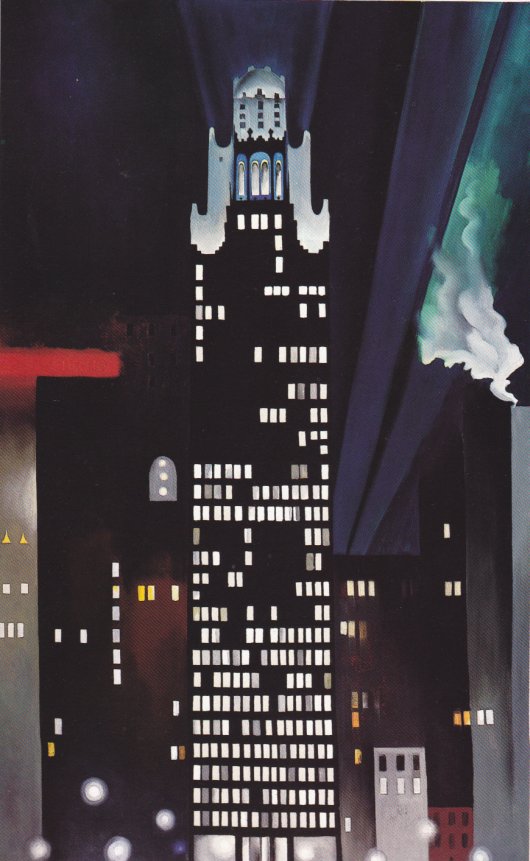

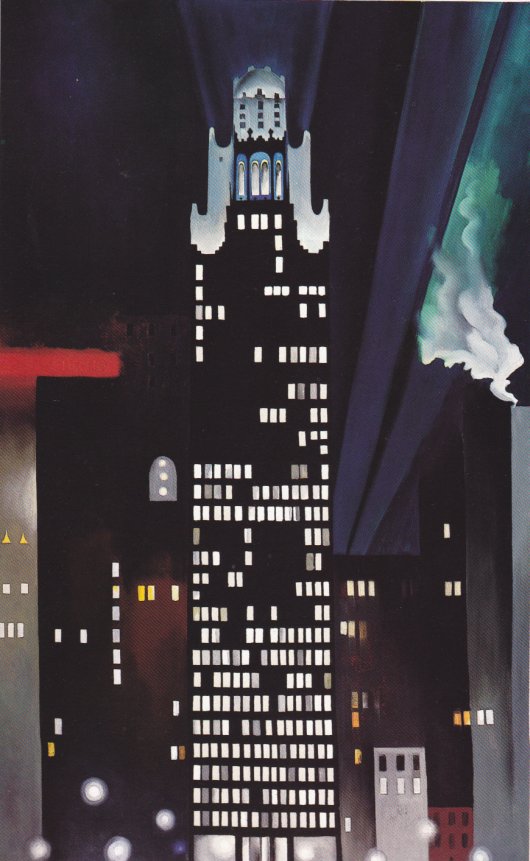

radiator bulding - night, new york, 1927

radiator bulding - night, new york, 1927

Cady Wells was an aspiring artist who decided to become a painter upon arriving in New Mexico in 1932. After O'Keeffe offered a slight criticism of one of his works - "maybe you fooled yourself a bit because it was so handsome" - he offered to throttle her. She apparently took no offense:

to Cady Wells

New York, late February 1938

Dear Cady:

No — Im not annoyed with you — and I dont care anything about your manners one way or the other — Your letter seems very normal and I like it that you are angry tho making you angry or whatever I did to you was not my wish or intention — I knew when I wrote that I was hurting the artist in you and I like it that you kick back and spit at me. It isnt that I have any particular liking for being treated that way but I like the artist standing yourself — believing in his own word no matter what anyone may say about it. Believing in what one does ones self is really more important than having other people pat you on the back. There really isn't any reason for you to be so annoyed with me that you want to choke me for saying that your things are very good and will see — I dont see anything so awful about that remark — It simply means that I think you are keyed in a way with your time so that people will like what you do. The same thing could be said of me — I don't consider it a remark either for me or against me. It just happens to be a fact. — And as long as you make perfectly clear without actually saying it that you dont care what I think anyway — I cant imagine why you want to choke me — why bother — I very much doubt its being worthwhile. I am glad you have had such a good winter.

Maybe it will please you while you are thinking unpleasant things about me to think to yourself that my winter has not been so good —

You can say to yourself gleefully — serves her right!

However — it is pleasant enough now — a week of lovely spring sun — my hedge is all turning green and I am feeling fine again —

Wonder what we can fuss about next — probably everything.

G.

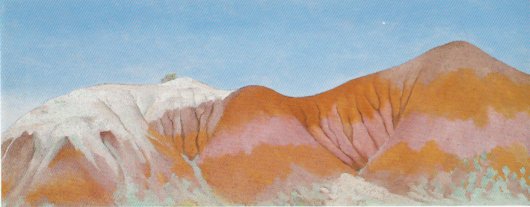

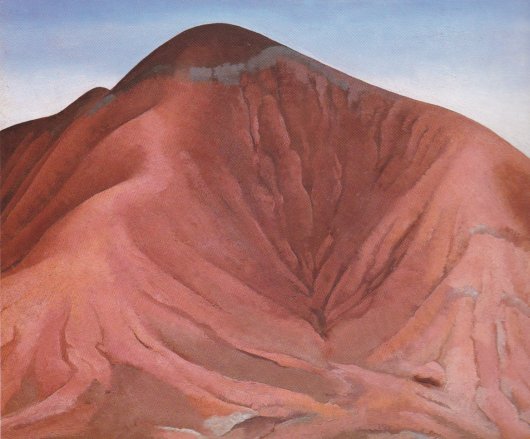

pedernal, 1945 O'Keeffe met the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright when she received an honorary degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1942. She would later refer to him as "one of my favorite people of our time."

pedernal, 1945 O'Keeffe met the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright when she received an honorary degree from the University of Wisconsin in 1942. She would later refer to him as "one of my favorite people of our time."

to Frank Lloyd Wright

On the train from Chicago to New York

May 1942

Thursday afternoon

Dear Frank Lloyd Wright,

I wish that I could tell you how much the hours with you mean to me — I've thought of you most of my waking hours since I left your house and I assure you that I left with a keen feeling of regret

Last night in the hotel in Chicago — my sister gone on to Cleveland to meet her husband — I got out your book. I read the part marked with the red line at the end — then started at the beginning and read to the end of the first evening — stopping often to think about it — always relating what you give me to painting — to what I want to do — and you may smile when I say to you that I thought seriously of taking the train back to Madison to visit you again — I thought too — if I had offered you one of my best paintings years ago — maybe you would have taken it — I remember that even then — so long ago — that was what I wanted to do even tho I did not know you as I do now — I felt that I should offer you my best but I knew Alfred would make a great stir if I started doing things like that —

I have always said to him that I think I should give things away — that it would be alright — and he always says — "Yes — it would be if you were alone — but it wouldn't be while I'm around"

Since I visited you I know that my feeling was right for me. Two together aren't the same as one alone —

As I think over this whole trip — the hours with you are the only part of it that I feel really add to my life —

I salute you and go on to the second evening of your book with very real thanks

Will you give a very quiet greeting and thanks to the beautiful wife

Sincerely

Georgia O'Keeffe

It was Anita Pollitzer who encouraged Georgia to become involved in the cause of women's liberation.

to Eleanor Roosevelt

Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt

29 Wash. Sq. W.

N.Y.

Having noticed in the N.Y. Times of Feb. 1st that you are against the Equal Rights Amendment may I say to you that it is the women who have studied the idea of Equal Rights and worked for Equal Rights that make it possible for you, today, to be the power that you are in our country, to work as you work and to have the kind of public life that you have.

The Equal Rights Amendment would write into the highest law of our country, legal equality for all. At present women do not have it and I believe we are considered — half the people.

Equal Rights and Responsibilities is a basic idea that would have very important psychological effects on women and men from the time they are born. It could very much change the girl's idea of her place in the world. I would like each child to feel responsible for the country and that no door for any activity they may choose is closed on account of sex.

It seems to me very important to the idea of true democracy — to my country — and to the world eventually — that all men and women stand equal under the sky —

I wish that you could be with us in this fight — You could be a real help to this change that must come.

Sincerely

Georgia O'Keeffe

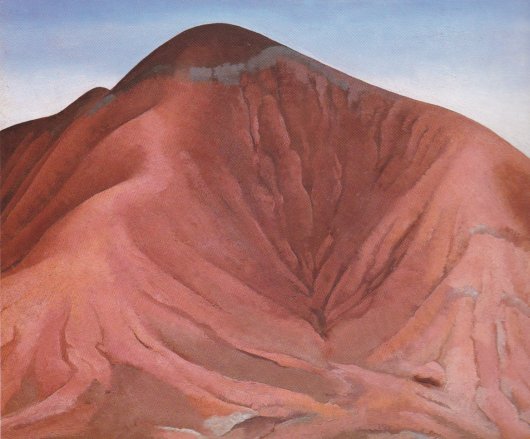

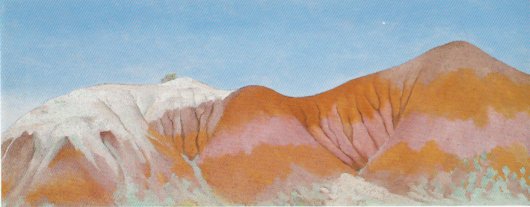

near abuquiu, new mexico - hills to the left, 1941 to Cady Wells

near abuquiu, new mexico - hills to the left, 1941 to Cady Wells

Abiquiu, early 1940s

Cady — it is Monday night — and I must write you as you did not come because I have thought so much you — to you. I really did not think you would come but I hoped you would — I wanted to walk through my world here with you — up to the cliffs — the bare — open space — then back down another area where the water drains and there are trees and big bushes — tonight — at sunset I walked alone out through the red hills — I thought of you — wished you were with me but I get a keen sort of exhilaration from being alone — it was cold enough to wear a woolen jacket — I walked some distance — then climbed quite high — a place swept clean where the wind blows between two hills too high to climb unless you want to work very hard — I didn't want to climb so high — it was too late — but from where I stood it seemed I could see all over this world — When the sun is just gone the color is so fine — and I like the feel of wind against me when I get up high — My world here is a world almost untouched by man — I feel that your world out there has been colored by the soul of the Mexican

— I really dont know why I should so much wish you to walk with me through what is just outside my door — unless it is that I think it almost the best thing to do that I know of out here — it is so bare — with a sort of ages old feeling of death on it — still it is warm and soft and I love it with my skin — and I never meet anyone out there — it is almost always alone — I wanted you to walk through it with me like I wanted you to go to hear Marian Anderson sing — it is one of the best things I know of — Well — you did things you really wanted to do I am sure — the days must have gone very fast. I did not realize till this afternoon when I counted up the days on my fingers that you must be leaving either today or tomorrow — It was very good to see you — I have really become very fond of you —

Georgia

Although the following letter is undated, it was likely sent around the time of the second world war.

to Cady Wells

On the train from New York to New Mexico

Saturday morning

Cady!

I am in the beautiful country — our beautiful country — It is quite green — cloudy — and very cool — And Oh Cady — how I love it — it is really absurd in a way to just love country as I love this — I think of you and I wish for you to return to this soon

I'll always be having that in my head and in my heart for you hard

G.

You can find more of Georgia O'Keeffe on This Recording here.

I feel a sort of fury when you say that you wont succeed — I want to shake you to your senses — shake such an idea out of you for always — Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant — There is no such thing — Making your unknown known is the important thing

letter to Sherwood Anderson, 1923

"Under the Weather" - Book Club (mp3)

"Ain't Gonna Drink No More" - Book Club (mp3)

"Tell Me You Don't Tell Me Lies" - Book Club (mp3)

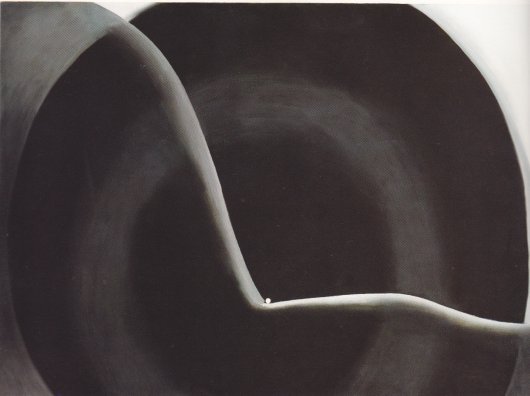

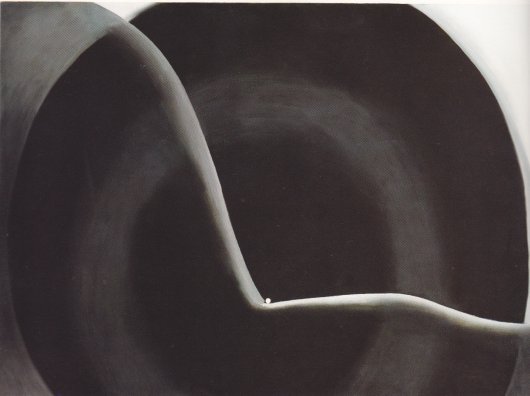

black abstraction, 1927

black abstraction, 1927

ART

ART  Friday, January 13, 2017 at 11:45AM

Friday, January 13, 2017 at 11:45AM

Edward Steichen's photograph of Kitty and Alfred Stieglitz

Edward Steichen's photograph of Kitty and Alfred Stieglitz  O'Keeffe and Stieglitz much later, in 1944

O'Keeffe and Stieglitz much later, in 1944  Kitty Stieglitz photographed by her father with her uncle Joseph

Kitty Stieglitz photographed by her father with her uncle Joseph Dorothy Norman

Dorothy Norman Into his life at this time came Lady Chatterly's Lover, his new favorite book.

Into his life at this time came Lady Chatterly's Lover, his new favorite book. Alfred's photograph of Dorothy Norman from behind

Alfred's photograph of Dorothy Norman from behind  Stieglitz's self-portrait, 1890

Stieglitz's self-portrait, 1890