TV

TV « In Which We Return To Twin Peaks At Some Point »

Monday, May 22, 2017 at 12:39PM

Monday, May 22, 2017 at 12:39PM The following review covers the first two parts of Twin Peaks: The Return.

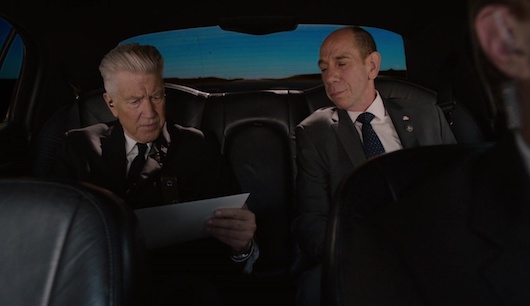

David Lynch: The Return

by ELEANOR MORROW

Twin Peaks: The Return

creators Mark Frost & David Lynch

Showtime

The burning corpse of Twin Peaks that David Lynch left behind when network executives and his partner Mark Frost tried to fuck with his creation at the end of 1980s has been alight for twenty-five disturbed years. Lynch has examined volume after volume of his dreams and committed them to film since those halcyon days. Some of his efforts, like 2001's Mulholland Drive exceeded his original vision for Twin Peaks; others became a bit overcomplicated for even his most devoted fans, even if the cinematography itself was typically one-of-a-kind.

The burning corpse of Twin Peaks that David Lynch left behind when network executives and his partner Mark Frost tried to fuck with his creation at the end of 1980s has been alight for twenty-five disturbed years. Lynch has examined volume after volume of his dreams and committed them to film since those halcyon days. Some of his efforts, like 2001's Mulholland Drive exceeded his original vision for Twin Peaks; others became a bit overcomplicated for even his most devoted fans, even if the cinematography itself was typically one-of-a-kind.

This Lynch cares about pleasing no one again. It is in his very capable hands that we find Agent Dale Cooper (Kyle MacLachlan). The fifty-eight year old performer is remarkably well preserved, which makes thematic sense because he has been in another dimension, the Red Room, for all of this time. His dark doppelganger (Kyle MacLachlan with shoulder-length black hair) is in North Dakota, where two murders have taken place when Twin Peaks: The Return opens.

Two clueless cops find the head of a librarian in her apartment, the eye blasted out of its socket. After turning back the blanket, they find the torso of an obese John Doe mismatched to her pretty head. The local school principal Bill Hastings (Matthew Lillard) is the number one suspect, since his prints are found all over the librarian apartment and he knew the victim. In a few relatively straightlaced scenes, Frost and Lynch give us half the pleasure found in the original Twin Peaks: that the show was at its most amusing and poignant when it fundamentally dealt with the mundane.

The other half of Twin Peaks was the wild, spooky melodrama of the Black Lodge, where a demon possessed inhabitants of this Washington town. The moments in Twin Peaks: The Return when Agent Cooper struggles to free himself of his interdimensional confinement are replete with hokey, yet unnerving special effects, and the visuals are at times outright frightening. Lynch takes us to a room in midtown Manhattan where a young man views a glass box. His only job is to see if anything appears in it.

Such a set-up, ominously underscored by Angelo Badalamenti's haunting score, is a metaphor for the open possibilities of Twin Peaks, the town. We return to the familiar residents of the place for good at the end of the second episode. The eternally handsome James Hurley (James Marshall) is still wearing his leather jacket, observing the table where Shelly Johnson (Mädchen Amick) sits with friends. It is in these nostalgic moments where we suddenly realize how grateful we are that this is nothing like the Twin Peaks of decades ago.

So much of the original Twin Peaks was a shocking, amusing send-up of what television had become. Rewatching any of the first run of the show now, it is easily to see how much of the television that followed came out of the feel and style that Lynch developed. The original show still gives off a modern feeling.

In order to shock us again, Lynch now has the benefit of premium cable standards and practices. Twin Peaks: The Return is frequently gruesome. It turns sexuality into a weird nothingness that fades before the everyday. Its characters are continuously waiting to be astonished by something in their lives, and when that ultimate moment arrives, they do not shy away. Boring people, Lynch insists, are not what they seem. They have their moments.

The original Twin Peaks had one key flaw that makes the show rather difficult to watch at times. That was the performance of Michael Ontkean as Sheriff Harry Truman. Ontkean was straight out of central casting for all the lame cop shows that Lynch was half-parodying here, but since Twin Peaks exceeded what it was making fun of at nearly every turn, his awkward, stumbling performance just got in the way of Kyle MacLachlan, as Truman is forced to portray a clueless straight man in every scene.

Fortunately, Ontkean smartly gave up acting a number of years ago, probably because he was not very good at it. Replacing him are a bevy of newcomers. Some are Lynch's particular favorites, and some are actors he has admired but never had a chance to work with before. Since the individual scenes of Twin Peaks: The Return have every chance of making very little sense to the audience, the rapid pace of the cameos and casting against type helps turn the show into a bizarre retrospective of Lynch's career in film and television.

By the end of the second episode, Agent Cooper has freed himself from the Red Room, ending up in the glass box. A demon follows close behind, and the show intends to follow Cooper back to the town where his life properly began. The town's waterfall and school look nearly the same; its residents are somewhat aged.

Even amidst all the confusion, David Lynch creates so many new feelings and archetypes to exploit, and Twin Peaks: The Return is more gleeful than anything. His basic theme throughout each iteration of Twin Peaks is the continuous discovery of all the places where human dignity can be found, uncovered, and disbanded. Horror, for Lynch, is a pretext to a more elucidated understanding, and he finds this more easily in a phrase, an aside, or a vision that any commonly understood form of elegy or coda. That is why he never wanted Twin Peaks to solve the murder mystery that propelled it from scene-to-scene: because doing so would only mean a false catharsis. They were all the killers.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Manhattan.

david lynch,

david lynch,  eleanor morrow

eleanor morrow

Reader Comments