Science Corner: Motherfuckin' Psychedelic Frogfish Edition

by MOLLY LAMBERT

"When you're happy, known things, familiar things lose their appeal. Novelty, on the other hand, becomes more attractive."

A nursery for the extinct giant shark known as the megalodon — the largest shark that ever lived — has been unearthed in the Isthmus of Panama.

meep meep morp morp psychedelic frogfish la la la la freaking out ur facespace

Creativity often goes hand-in-hand with mental illness, such as schizophrenia. Now scientists think they know why: The brain responds differently to the "feel good" chemical dopamine in both schizophrenics and the highly creative, a new study suggests. The results showed similarities between the brains in healthy, highly creative people and those with schizophrenia.

The findings suggest that creative types might not be able to filter information in their heads as well as "normal" folks, leaving them better able to make novel connections and generate unique ideas. "Thinking outside the box might be facilitated by having a somewhat less intact box," said study researcher Fredrik Ullén, of the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm, Sweden.

hey hey hey hey psychedelic frogfish blorp blorp blorp blorp eatin all ur cupcakes

Ultimate Neg: What do you do if you want more sex but your partner is about to leave? How about scaring the fucking shit out of her. The male topi antelope keeps his mate around by snorting deceptively, a pretense that makes her think leaving him will bring her face-to-face with danger, scientists now reveal.

Although justice is supposed to be "blind" a study finds that attractiveness influences conviction and sentence length. Cornell University researchers found that unattractive defendants are 22 percent more likely to be convicted, and tend to get hit with longer, harsher sentences – with an average of 22 months longer in prison.

A "dracula" fish with canine-like fangs, a worm that launches glow-in-the-dark bombs and a psychedelic frogfish are among the Top 10 new species discovered last year.

Scientists have identified areas of the brain that, when damaged, lead to greater spirituality. The study involves a personality trait called self-transcendence, which is a somewhat vague measure of spiritual feeling, thinking, and behaviors. Self-transcendence "reflects a decreased sense of self and an ability to identify one's self as an integral part of the universe as a whole."

Same Brain Spots Handle Sign Language and Speaking

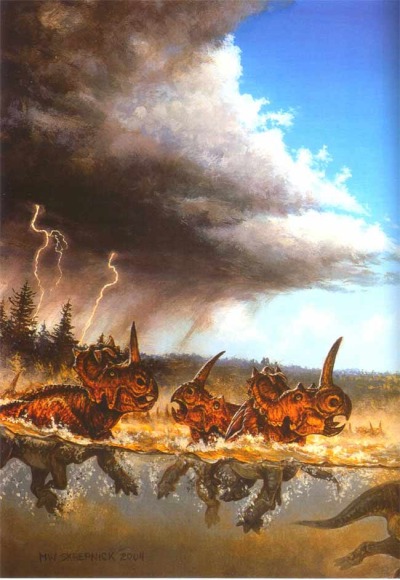

World's Largest Dinosaur Graveyard Linked to Mass Death. The dinosaurs may have been part of a mass die-off resulting from a monster storm, inspiring the world's greatest illustration (above).

When you have a "Eureka!" moment, not only does an answer seem to suddenly flash into your head, your brain neurons shift gears just as rapidly, a new study suggests. The results, found in rats, pinpoint these moments to an area of the brain called the prefrontal cortex, supporting the idea that learning can involve sudden changes in the brain, rather than a gradual process.

"We found the biggest drop in empathy after the year 2000." Compared with college students of the late 1970s, current students are less likely to agree with statements such as "I sometimes try to understand my friends better by imagining how things look from their perspective," and "I often have tender, concerned feelings for people less fortunate than me." HOW BOUT THAT ECONOMY FOLKS?

"Monitor lizards are fantastic creatures. They are agile, powerful, and the most intelligent lizards of the world."

Trusting women become more skeptical when they are given doses of the sex hormone testosterone, a new study suggests.

Drinking coffee could help to prevent the neural degeneration associated with brain disorders and aging, scientists say. I LOVE COFFEE!

A tubby dinosaur sporting horns each the length of a baseball bat roamed what is now Mexico some 72 million years ago. Horned dinosaurs may have hopped across islands to make their way into Europe, researchers now reveal.

"Brains don't kill people, people kill people"

Crop circle contains Euler's Identity, considered by many to be among the world's most beautiful and elegant theorems.

AND MOTHERFUCKERS ACT LIKE THEY FORGOT ABOUT DREN!!! (GO SEE SPLICE!!!)

A team of scientists says they have succeeded in creating the first living organism with a completely synthetic genome.

The key to intelligence may be the ability to juggle multiple thoughts or memories.

New Test Reveals Good vs. Bad Sperm

Human Mind 'Time Travels' When Pondering Movement: The ability to mentally meander through time by remembering the past or imagining the future sets humans apart from many other species, helping us to learn from what came before and plan for what lies ahead (wonder how this fits in with leaning while playing video games).

Remarkably little is known about how such mental time travel works. Thinking about moving forward prompted speculation about the future, while imagining moving backward triggered reflections on the past. Past research showed that our perceptions of time are tightly linked with space. For instance, pondering the future makes us lean forward, while recalling the past makes us lean back.

The dramatic rise in overall intermarriages has been partly driven by a large wave of immigrants from Latin America and Asia over the past several decades, along with a breaking down of longstanding cultural taboos against interracial marriages and the publication of Neel Shah's "How To Date A White Bitch."

Teen Brains wired for risk taking, being embarrassed by parents, saying "whatever" a lot, reenacting Valerie Faris and Jonathan Dayton's video for "1979."

Researchers investigated brain changes that occur when humans act courageously — that is, when we feel fear, yet act in a manner that opposes this fear. The results show activity in a brain region called the subgenual anterior cingulate cortex (sgACC) was associated with participants overcoming their fears

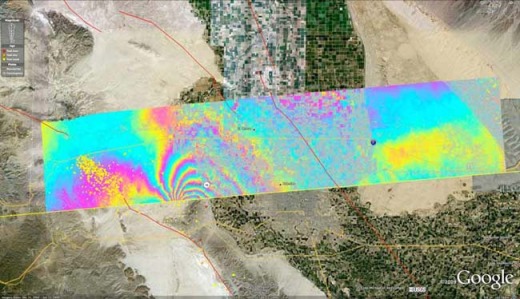

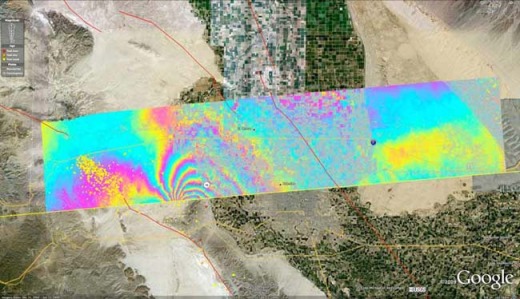

an earthquake moved the border city of Calexico 31 inches, shown above

An obscure compound known as pyrophosphite could have been a source of energy that allowed the first life on Earth to form, scientists now say.

In what urologists say is a growing phenomenon, adolescent boys are playing a game called sack tapping, in which the sole purpose is to strike someone in the testicles. The practice became national news after one victim, 14-year-old David Gibbons of Crosby, Minnesota, had to have his right testicle amputated from being sack tapped in the hallway between classes. Now he is the coolest kid in school.

Brain Quickly Remembers Complex Sounds. The study's results show that auditory memory is as impressive as visual memory, but in different ways, Pressnitzer said. While complex images can be remembered without repetition, audio memory seems to require that repetition take place in order to come into effect.

Naps Clear the Mind, Help You Learn

A girl diagnosed with ADHD as a child or teen suffers from major or clinical depression and anxiety disorders at much higher rates — 20-25 percent — than a boy with ADHD (3-8 percent). Professionals call this "co-morbidity" — when two disorders occur together. A girl with ADHD is far more likely to develop depression or anxiety than a girl without ADHD, or any boy in general. Hey who likes the internet.

About 10,000 gallons of water per minute gush up from the desert floor at an oasis near Death Valley, Nevada, but only after the water completes a slow 15,000-year underground journey,

Personality Predicted by Size of Different Brain Regions. Those who scored high on neuroticism — which indicates a tendency to experience negative emotions, including anxiety and self-consciousness — was associated with a larger mid-cingulate cortex, a region thought to be involved in the detection of errors and response to emotional and physical pain. Neurotics also had a smaller dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, a region implicated in the regulation of emotions.

Extroverts, those who are sociable, outgoing and assertive, had a larger medial orbitofrontal cortex, a region involved in processing rewards. This goes along with the idea that extroverts are sensitive to rewards, which in our society often involve social interactions and status. Conscientious people, who tend to be orderly, industrious and self-disciplined, had a larger middle frontal gyrus, involved in memory and planning.

What we consider "fair" changes as we age, a new study finds. Young children like all things to be equal, but older adolescents are more likely to consider merit when it comes to dividing up wealth, the researchers say. The shift from the "egalitarian" view of fairness to the more merit-based "meritocratic" view occurred largely between fifth and seventh grade, although it continued to change through high school, with seniors placing the most importance on achievement.

Habitual learning, as it's called, involves two brain circuits — one used for movement and the other for higher, cognitive thinking. As a task is learned, these circuits trade off in terms of their engagement. The movement circuit, which involves a part of the brain called the dorsolateral striatum, becomes more active, while the cognitive circuit, which involves a region called the dorsomedial striatum, takes a dip.

When the room was warmer, participants rated the character as more sociable compared with when it was colder. They also judged the experimenter in charge of instructing the task as more sociable when the heat was on.

Two previously unknown frog species have been identified from two sites in Panama, and they are already under threat from the deadly fungus that has wiped out many amphibian species and is poised to threaten many more. Researchers recognized that frogs (and other amphibians) around the world were dying off in large numbers in 1989. The cause: a deadly fungus called chytridiomycosis that is thought to kill its victims by clogging their skin, essentially suffocating them.

A new study found that homosexual men may be predisposed to nurture their nieces and nephews as a way of helping to ensure their own genes get passed down to the next generation.

A new class of man-made materials could hold the key to creating X-ray-like cameras that can see through walls and clothing. Called metamaterials, these substances could harness terahertz radiation, light with energies between infrared waves and microwaves. Terahertz waves are essentially low-level heat created by the movement of molecules.

46 percent of adults say they have used online searchers to find information about people from their past.

Older people in their mid- to late-50s are generally happier, and experience less stress and worry than young adults in their 20s.

Soft-bodied sea animals did not die off during a major extinction event during the Cambrian period, as previously thought.

Dads get post-partum depression too.

Scientists build living lungs in a lab. There is no language in them.

Normally when you see or imagine someone else in pain, your brain experiences a twinge of pain as well. Not so when race and bias come into play, scientists now find. People respond with empathy when pain is inflicted on others who don't fit into any preconceived racial category, such as those who appear to have violet-colored skin. When both white and black volunteers saw violet-colored hands get jabbed, they responded empathetically.

This suggests that people normally automatically feel the pain of others, and the lack of empathy that volunteers showed for people of other races was learned and not innate. (this is 4 my Na'vis who just lost somebody, ur best friend, ur baby)

"This default reactivity of human beings implies empathy with the pain of strangers," said researcher Alessio Avenanti. "However, racial bias may suppress this empathic reactivity, leading to a dehumanized perception of others' experience." It could make evolutionary sense that we feel less empathy for people who are different than us. "In case of war or even a friendly competition like a football game, it could be adaptive to feel less empathy for people we consider our opponents."

Molly Lambert is the managing editor of This Recording and resident science expert. She last wrote in these pages about Get Him to the Greek. She tumbls here.

"In the Flicker" - Sundowner (mp3)

"DLZ" - TV on the Radio (mp3)

"Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds" - The Black Crowes (mp3)

FILM

FILM  Tuesday, June 29, 2010 at 10:35AM

Tuesday, June 29, 2010 at 10:35AM

actual cast photo, 1978

actual cast photo, 1978  diana ross,

diana ross,  michael jackson,

michael jackson,  rea mcnamara

rea mcnamara