A Well-Poised Observer

by ALICIA PUGLIONESI

In 1927 Mary Craig Sinclair was having trouble keeping it together. The Long Beach, California home that she shared with her famous husband, Upton, belonged to stolid upper-middle-class America, but for Mary Craig, Long Beach was the end of the world, or the limit of the world. Nothing but a lonely stretch of sand stood between her front door and the “awe and wonder” of the Pacific Ocean. In this place, the laws of nature and human capability would stretch and break.

The Sinclairs settled in California in 1916, and a decade of radical crusading, political campaigns, and constant work was taking its toll on Mary Craig (who went by her middle name). She began to suffer from a nervous illness that left her debilitated and unable to leave the house. It does not diminish the reality of her physical suffering to add that her ailment was at least partly philosophical. Confined to her study, she sat down and tabulated the practical outcomes of the couple's grinding reform work: “At the rate we were going,” she wrote, “we would be old and gray before we could see much more than the beginning of the social changes for which we were striving...this was too slow!"

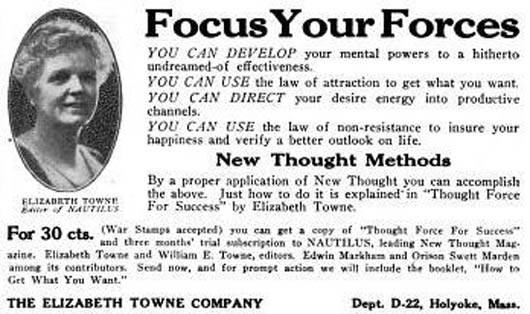

Like many Americans looking for solutions to problems that blur the lines between mental and physical, Craig started reading self-help books. When her doctors told her that the problem was all in her head, she delved into the literature of the mind cure, New Thought, and Christian Science, the most popular self-help doctrines of the day. These movements had many differences, but all focused on the capacity of the mind, through unknown mechanisms, to effect change upon the body, upon other individuals, and upon society – let's call these “powers of mind.” Captivated by the promise of a cure, Craig was nevertheless troubled by the suspicion that a placebo effect was at work, rather than genuine telepathy that supposedly allowed mind healers to treat distant patients.

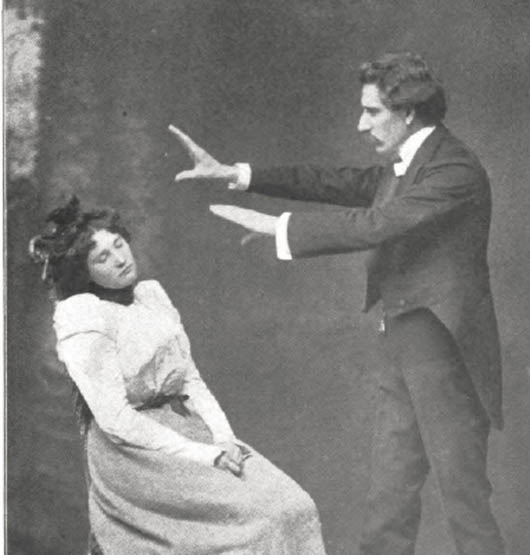

Interest in powers of mind was quite normal for an upper-middle class, educated woman like Craig – crazes for telepathy, hypnosis, and spirit communication had come and gone in the United States and Europe for the past hundred years. Rather than a clear divide between “science” and “the paranormal,” Americans applied an experience-based epistemology to judging such phenomena on a case-by-case basis. That is to say, they trusted a thing they called common sense, inherent to almost all people of respectable social and economic status – particularly the growing middle class. If they could experience powers of mind firsthand or through trusted testimony, and satisfy their curiosities and doubts, ordinary people were inclined to accept the extra-sensory as a matter of common sense.

Grolier's The Book of Knowledge (1931)

Grolier's The Book of Knowledge (1931)

Psychical research emerged in Britain in the 1870s, as an amateur science devoted to the investigation of the human mind and its possibilities – most particularly, to discovering factual evidence of the survival of the soul after death. This was actually quite a respectable pursuit, sharing the scientific territory of psychology and psychiatry; however, it sought to undermine the materialist basis upon which scientists were constructing a new, secular reality for the twentieth century. Historians who bother with such dead ends call it a “last gasp of metaphysics,” a search for spiritual reassurance in the wake of Darwinism and the hollow materialism of modernity. The practical work of British psychical research was mostly seances and ghost hunting.

This project spread to the U.S. in the 1880s, but psychical research would lead a very different life here. Ordinary Americans were already debating over spirit mediums, telepathic performers, and mental healers. Newspapers, magazines, and books were filled with the stuff. People wanted scientific investigation to uncover the mechanisms of powers of mind, but many people felt that the most important standard of evidence was their own witnessing.

Founded in 1884, the American Society for Psychical Research (ASPR) boasted many eminent men of science among its members, along with the heads of universities and government research bureaus. Thousands of people submitted reports of paranormal experiences in the hope that the ASPR's experts could verify or explain what had happened to them.

Let's return to Mary Craig Sinclair, who, in 1927, wrote an impassioned letter to the ASPR regarding a series of psychical experiments which she organized among her friends in Long Beach. “It is very different to see such a phenomena than to read of it,” she remarked, explaining how her research into the mind cure led her to seek out an actual psychic medium and invite him into her home. She wanted to test the reality of telepathy, because, if scientifically verified, “it meant a new philosophy, a new religion! And a relief from Socialism!"(Upton had, at that time, run for Congress twice on the Socialist ticket.) Although Craig was a special case in that she married a man of radically materialist politics, her situation was emblematic of a widespread desire for spiritual meaning in the midst of secular modernity.

Ostoja with Leo Tolstoy

Ostoja with Leo Tolstoy

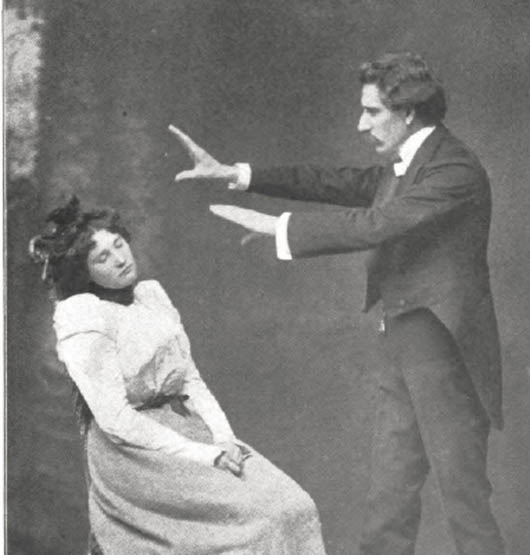

The psychic, who called himself Count Ostoja, provided Craig with astonishing evidence for telepathy. A popular stage medium, his act involved entering a trance state in which he could be buried alive or impaled with various sharp implements. He also practiced mind cure techniques and hypnosis. Craig faced a moment of choice: she could ask him to cure her nervous illness, with the possibility that he merely employed auto-suggestion, or she could investigate Ostoja scientifically to determine the ultimate truth of the mind cure. “I decided I did not want to be hypnotized,” she explained, “because this might incapacitate me as a judge of his work – as I would be under his influence. She asserted that “I couldn't rest without knowing whether [telepathy] was real and usable.”

Craig tried to establish herself as a credible witness, motivated by scientific curiosity rather than the selfish desire for physical or spiritual comfort. Her nervous symptoms faded away as she threw all her energy into organizing a rigorous investigation of Ostoja. It was time for that cocktail party of the occult, the séance.

Craig secured the home of Paul Jordan Smith, a prominent literary critic who she hoped might take an interest in Ostoja and help with his rather costly upkeep. Next, she assembled a séance group of trustworthy observers. They didn't need scientific backgrounds – on the contrary, Craig was skeptical of professional science and medicine. Doctors, in her view, were the worst perpetrators of narrow-minded materialism. Scientists were a bit better due to their “patient, exact method of observation and criticism” – they made excellent witnesses as long as they could reign in their professional “repugnance towards unexplained things." Thus, Craig invited a few “prominent scientists and medical men” in part to render the spectacle of unexplainability especially piquant.

the sinclair home, 1934

the sinclair home, 1934

More than professional credentials, the séance group needed a reputation for common sense. Paul Jordan Smith, the critic, was “a professional sceptic [sic] of the whole Universe,” while his wife, Sarah, was “almost stolidly materialistic; she could never be emotional.” As a final proof of the group's complete lack of preconceptions, Craig declared that “none of them had ever before seen any psychic phenomena, nor had they ever read anything on the subject, though all of them are highly educated and cultured.”

The phenomena of the séance itself are a void at the center of this rhetorical apparatus of witnessing. There are no notes from that evening. Rather, Craig collected numerous statements from witnesses affirming that the medium had not cheated and the phenomena appeared completely genuine. These statements included criticisms of Craig's own conduct during the séance, as if to prove that she had not influenced the testimony. Both Paul Jordan Smith and Melville Ellis, a local physician, accused Craig of trying to influence the medium with her gestures. They claimed that this could not have influenced the outcome because Ostoja's eyes were closed, but suggested that Craig might be lacking in scientific rigor.

It is almost as though the particulars of the psychical phenomena – what exactly was said, heard, and felt by the séance guests – were irrelevant. What mattered was the fact of their experience, an experience attested to by upstanding individuals.

For whom was Craig crafting this very canny representation of the Ostoja case? For what judge did she assemble her evidence? Craig was plagued by doubts about Ostoja, and about her own powers of judgment. She could not rest assured that telepathy had been proven for all time during that summer evening in the Smith's parlor. Although she had “kept in mind the danger of 'believing what we want to believe,' I cannot be certain that I have escaped this danger.”The evidence of her psychical experiment survives because she bundled it together and sent it to Walter Franklin Prince, a leader of the ASPR. She begged Prince to come to California to examine Ostoja and verify his phenomena.

In pleading letters to Prince, Craig repeatedly underlined the problem of subjectivity, self-deception, and inexperience. “My interest in Ostoja's demonstration reaches the point of excitement, perhaps even over-emotionalism...I was not a well-poised observer,” she wrote, but “I do not want you to think I am at all times unfit as a witness. Although Craig possessed a bounty of common sense – both her husband and Prince attested that she could be practically “cold-blooded” in her “skeptical point of view” – she could not help but doubt her own senses when they attested to something as fantastical as telepathy. In search of objectivity, she sought the authority of experts.

“Clairvoyance” George Cruikshank (1845)

“Clairvoyance” George Cruikshank (1845)

For Mary Craig Sinclair and the members of her séance circle in the 1927, the experience of astonishment was still essential to producing knowledge of psychical phenomena. Americans of an earlier generation had enshrined this experiential knowledge as the gold standard in judging the claims of mind cure, mesmerism, and Christian Science. The appearance of the ASPR in the 1880s created a new source of authority, a group of experts with the imprimatur of proper science – some observers were better than others, and some experiences more valid.

Craig never persuaded Walter Prince to come to California. The trip was too expensive for the cash-strapped ASPR, and too long and exhausting for the aging Prince. Sifting through the onslaught of frantic letters from Craig, one can understand his lack of enthusiasm. Prince had explained early on in their correspondence that Ostoja was simply the new stage name of a performer that the ASPR had already investigated and found to be a fraud.

This rejection didn't persuade Craig to drop her seances or her pursuit of telepathy – instead, it sent her off on an even more eccentric course. By the time she was done with the hapless Count Ostoja, Craig claimed to have turned his own powers of mind against him. The only way to judge the reality of the phenomenon, she concluded – rejecting scientific authority and returning to the primacy of experience – was to master telepathy for herself.

Alicia Puglionesi is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Baltimore. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She last wrote in these pages about the Personal Pelvic Viewer. She tumbls here.

The next part of this series will appear in early August.

The Best Of Alicia Puglionesi On This Recording Happens Now

Dream of a whorl without pain

Earliest autobiography of Margary Kempe

History of the contraceptive douche

Stands at the vanishing point

The effect of the Dalkon Shield

A woman at home views herself

"Five Senses (Everything Will Change)" - The Wild (mp3)

"There's A Darkness (But There's Also A Light)" - The Wild (mp3)

Tuesday, January 12, 2016 at 10:20AM

Tuesday, January 12, 2016 at 10:20AM