BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Accept Margery Kempe As A Holy Person

Friday, July 31, 2015 at 11:08AM

Friday, July 31, 2015 at 11:08AM

This Creature

by ALICIA PUGLIONESI

Margery Kempe wrote one of the earliest autobiographies in the English language, except that she didn't write it. Kempe dictated her life story to a scribe because, like most medieval women, she was illiterate. This resulted in a number of strange effects, the most jarring of which is that the scribe replaced her first-person “I” with the phrase “this creature” throughout the text. It's possible that Kempe spoke in the third person as "this creature." Some scholars suspect that she was secretly literate and wrote the book herself, taking pains with the story of the male scribe and the elimination of personal pronouns in order to evade persecution.

Other scholars question whether Kempe existed at all because her story is so profoundly strange.

Already this creature leads us into a tangle of difficulties: was Margery Kempe a radical who cannily manipulated religious and social conventions in order to live a life beyond the limits set for women of her time? You wouldn't think so looking at her. In her book she sometimes seems like a wild, frightened animal in our modern sense of “creature." Or a creature in the sense of a monster, suddenly strange and frightening to herself, desperately seeking an escape into the divine. All creature really means in the fifteenth century, though, is a thing that God created, and over which he has dominion. The Book of Margery Kempe is about a normal woman who believes that God chose her – because of her lack of any special merit – to demonstrate how his divine love transcends all human conventions. The question, of course, is whether the bulldozing of those conventions was God's idea or Kempe's, and whether we could ever tell the difference.

Already this creature leads us into a tangle of difficulties: was Margery Kempe a radical who cannily manipulated religious and social conventions in order to live a life beyond the limits set for women of her time? You wouldn't think so looking at her. In her book she sometimes seems like a wild, frightened animal in our modern sense of “creature." Or a creature in the sense of a monster, suddenly strange and frightening to herself, desperately seeking an escape into the divine. All creature really means in the fifteenth century, though, is a thing that God created, and over which he has dominion. The Book of Margery Kempe is about a normal woman who believes that God chose her – because of her lack of any special merit – to demonstrate how his divine love transcends all human conventions. The question, of course, is whether the bulldozing of those conventions was God's idea or Kempe's, and whether we could ever tell the difference.

People have wondered what was wrong with Margery Kempe for centuries: was she insane, possessed, divinely-inspired, or incredibly canny? She was known for weeping uncontrollably at inappropriate times – like in the middle of a church service, or while traveling with strangers, or while trying to persuade a local mob that she wasn't a heretic who should be burned at the stake. Kempe didn't see her incessant crying as a problem. She thought it was a gift from God – God had chosen her for this form of penance, a mark of difference and divine favor. She seems to have spent a lot of her time sitting or lying down and weeping for the soul of mankind.

This was the late fourteenth century, a time of some political tension and much religious strife in Europe. The Catholic Church was working hard to bring its authority to bear on heretical sects like the Lollards that claimed direct communication with God. The Church found that communication with God was a particularly slippery thing to regulate. A complex set of rules and hierarchies mediated Catholic access to the divine, but the religion was based on stories of ordinary people receiving unexpected revelations. This contradiction was becoming a sticking point. Margery Kempe is a footnote in the long and messy run-up to an even longer and messier schism; her hedge was that none of her words or actions were her own, a common-enough maneuver for speaking truth to power.

Medieval religious devotion was also passing through a sort of ecstatic sentimental phase around this time. Passion and weeping, fantastic love and impossible longing, became popular expressive paradigms, to the consternation of the Church which just wanted people to behave in an orderly fashion.

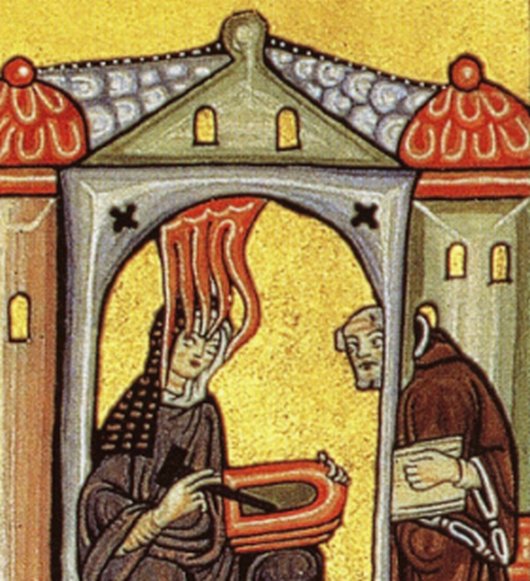

Since this “affective piety” was coded feminine, some interesting gender issues surfaced – there's talk of suckling at Jesus' teat and quasi-sexual encounters with the godhead. Revelations about the ecstatic nature of God's love came from a new class of religious mystics, many of them women cloistered in religious orders. Marie d'Oignes, St. Bridget of Sweden, Clare of Montefalco, and Julian of Norwich were popular subjects of the female sacred biography genre – texts usually written by male clerics which authorized the spiritual experiences of holy women. Because these women were nuns they could often read and write, but their stories had to be told by men in order to assimilate material that could otherwise pose a danger to the Church.

can I help you with that ma'am?

can I help you with that ma'am?

Margery Kempe claimed never to have read any of the mystic texts popular during her lifetime, although she would at least have heard some of them read aloud. She was the daughter of a wealthy merchant in Bishop's Lynn, a town a hundred miles north of London. The mature Kempe describes her young self as “set in great pomp and pride of the world.” This means she liked to wear fashionable clothes. She was never "content with the goods that God had sent her...but ever desired more and more.” This means that she had an entrepreneurial streak; she ran a brewery and a grist mill. This seems like a medieval approximation of our modern feminine ideal: a woman who runs her own local, independent business and looks good doing it.

When she was twenty, Kempe married a local merchant and quickly got pregnant. The pregnancy was rocky – she was sick and bedridden, and after a difficult birth she “despaired of her life, thinking that she might not live.” Fearing death, Kempe called for a priest and tried to confess to him a dark secret. Keep in mind that matters of Catholic dogma and heresy were very, very serious for ordinary people in the Middle Ages: Kempe's dark secret was that “she was ever hindered by her enemy, the devil, evermore saying to her that...she needed no confession but could do penance by herself alone, and all should be forgiven.”

She had arrived, on her own, at the heretical belief that one could deal directly with God without the church as an intermediary. This was so heretical that the priest wouldn't even hear Kempe out – he cut her off in the middle of her deathbed confession. Without a confession Kempe knew that she was doomed to Hell for all eternity. At this point, she went completely nuts.

no confession? too bad.

no confession? too bad.

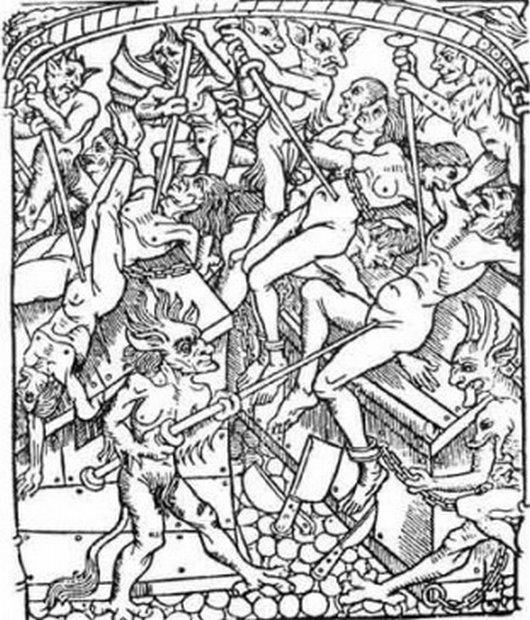

Or as she describes it: “This creature went out of her mind and was wonderfully vexed and labored with spirits for half a year, eight weeks, and some odd days. And in this time she saw, she thought, devils open their mouths, all inflamed with burning flames of fire...and [they] bade her that she should forsake her faith...she slandered her husband, her friends, and her own self...she knew no virtue nor goodness...she would have killed herself many a time with her stirrings, and have been damned with them in hell...save she was bound and kept with strength both day and night so that she might not have her will.”

Kempe was tied up in the basement for six months. This was a common medieval strategy for handling what we would call mental illness – modern readers have diagnosed her with everything from schizophrenia to postpartum depression. Finally, one day she had an ecstatic vision in which Christ appeared beside her and ordered her not to forsake him, “and anon the creature was stabled in her wits and in her reason as well as ever she was before.” Kempe's servants untied her and she vowed to devote her life to piety and prayer in thanks for her miraculous recovery. Except that she really liked nice clothes and money, and having sex with her husband. She basically went back to business as usual.

Only after her brewery and grain mill failed and she'd given birth to ten more children did Kempe have another mystical vision ordering her to forsake the things of this world and devote herself to Christ. She interpreted her commercial failure as God's punishment for pride and covetousness. And she wanted to interpret the voice in her head as the voice of God. This time, perhaps with less to lose, Kempe embarked on a mystical odyssey that would take her from Bishop's Lynn to London to Jerusalem, often penniless and at the mercy of suspicious strangers.

When she started weeping uncontrollably in public and preaching about the joy of heaven, her neighbors suggested that she was either mad or possessed by the devil. Kempe, herself fearing that this might be the case, sought explanations for her strange experiences. She consulted the female mystic Dame Julian of Norwich and many other ecclesiastical experts, all of whom reassured her of the authenticity of her visions. She worked her ecclesiastical connections hard – perhaps aware of the precariousness of her position, she shored up support wherever possible.

The biggest obstacle to Kempe's career as a mystic was her status as a married woman. At that point, the Church was advocating celibacy as the highest ideal for all of its followers – everyone who wanted to win God's love and forgiveness was supposed to give up sex. Previous female mystics had been celibate nuns, or widows who became celibate nuns, or virgins forced into marriage who got their husbands to take vows of celibacy before the deal was consummated. Virginity was the centerpiece of female holiness, but Kempe had been popping out babies for years and wasn't able to stop as long as her husband claimed his legal rights over her. She cut a deal that epitomizes her strange intermingling of sacred calling and worldly savvy: she got her husband to sign a vow of marital chastity in exchange for her paying off all his debts.

Even with a piece of paper certifying her (renewed) chastity, Kempe was a tough sell for many of her countrymen. People complained about her flamboyant weeping and wailing, accusing her of overacting. Kempe considered their hatred another test that God wanted her to endure – the more people scorned her, the more highly she would be rewarded in heaven. It seems like she was genuinely difficult to be around – her fellow pilgrims ditched her on the way to Jerusalem, and clerics back in England kicked her out of services because of her disruptive weeping. Her chaste husband, a remarkably loyal supporter of her work, tended to make himself scarce when Kempe started a scene in the public square.

There was still suspicion that Kempe “had the devil in her.” She carried on extensive conversations with God, Christ, and various saints, who she describes as speaking directly to her mind or soul, but the trick of medieval demonology is that demons could masquerade as holy figures in order to plant seeds of evil. Most of the ecclesiastical experts who Kempe consulted chose to interpret her visions through the lens of divine revelation, but many laypeople assailed her motivations as selfish, and her voices as demonic. Madness wasn't off the table either: one friar banned Kempe from his sermons on the grounds that she was not having visions, but rather suffered from a mental disease.

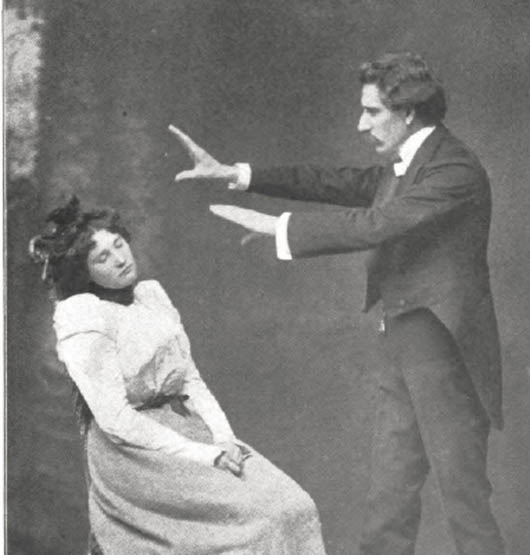

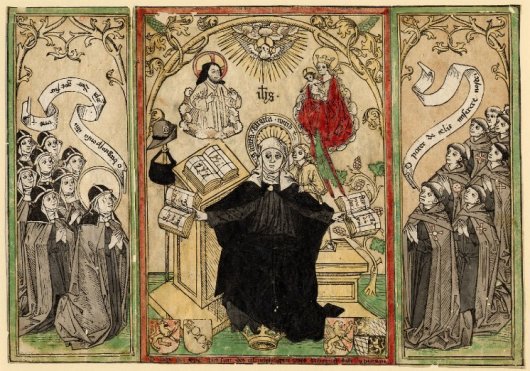

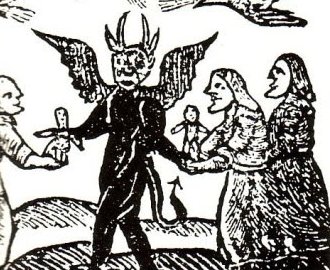

ways to be mistaken for a witchThe thing is that Kempe could be awfully convincing. Claiming illiteracy, she impressed religious authorities by reciting obscure Biblical passages and offering exegeses. She made accurate prophesies and fielded theological queries. Many ordinary Catholics accepted Kempe as a holy person and paid her to weep (copiously) for the salvation of their souls. Kempe won for herself freedoms and intellectual possibilities that were completely off-limits for most women of her time. Just in terms of mobility, she made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and visited scholars and mystics all over England, when most women weren't allowed to leave their villages without the permission of husbands and church officials. At times she publicly criticized the Church for corruption, and urged women to leave their husbands and become brides of Christ.

ways to be mistaken for a witchThe thing is that Kempe could be awfully convincing. Claiming illiteracy, she impressed religious authorities by reciting obscure Biblical passages and offering exegeses. She made accurate prophesies and fielded theological queries. Many ordinary Catholics accepted Kempe as a holy person and paid her to weep (copiously) for the salvation of their souls. Kempe won for herself freedoms and intellectual possibilities that were completely off-limits for most women of her time. Just in terms of mobility, she made a pilgrimage to the Holy Land and visited scholars and mystics all over England, when most women weren't allowed to leave their villages without the permission of husbands and church officials. At times she publicly criticized the Church for corruption, and urged women to leave their husbands and become brides of Christ.

To call Kempe's career subversive, though, would be to overlook the very real affective power of faith in medieval life. Maybe she got something she wanted – freedom to think and travel, freedom from endless childbearing – but she was also tormented by desire for what she had given up. The “things of this world” were the things that had offered her the most satisfaction; she particularly struggled with the demands of chastity. Her visions were sometimes terrifying and visceral, and she describes these traumatic episodes as tests of her love for God. Perhaps the deeply Catholic worldview of her age drove Kempe to a life of torment and self-denial, perhaps it equipped her to make sense of destabilizing psychological experiences. For a lowly creature who had surrendered her will to God, she managed to leave a highly personal record of her interior world – Kempe's voice is incredibly rich, simultaneously familiar and strange. This richness of voice may be all we need to know about her.

Alicia Puglionesi is the senior contributor to This Recording. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here.

"Giorna" - Jeremiah Jae (mp3)

"Fallen Saints" - Jeremiah Jae (mp3)