Versus Godard

by BERNARDO BERTOLUCCI

Is everything permitted to the one who loves? For example to spy through the slats of the blinds, or to seek in the beloved's garments the signs of his intimacy, or to rummage in his pockets to touch all the objects that, proofs of his betrayals, become proofs of his existence...

Strong in the love that I have for the cinema of Godard, I fish here in troubled waters, and I discover, precious as only the "real" can be, the "vulgarity” of Godard.

I am speaking of Godard‘s two most recent films, which I saw recently in Paris, their sound mixing scarcely finished, in the following order: Deux on trait chases que ie suit d’elle (Two or Three Things I Know About Her); five minutes of recreation (those are Godard’s words, or as, laughing, he said to me "fine del prime tempo”—end of the first part); then, Made in USA.

I think Godard expects a single judgment on these two films; he finished filming Made in USA one summer Friday and began Two or Three Things the following Monday. He edited the two films at the same time, probably in two connecting cutting rooms, like two hotel rooms for an illicit couple. Another prosaic observation — the order in which Godard showed these two films lets one suppose that he prefers Made in USA projected last. (Dulcis in fundo.)

Godard must be a great devourer of newsprint; one can find the origin of his two films in last months' newspapers. The idea for Two or Three Things: comes from a news item read in Le Nouvel Observateur: a married woman (about thirty years old), mother of two children, living in some housing development, prostitutes herself each time the desire seizes her to transform herself from mother of a family to consumer of all those products that neo-capitalism offers to Frechwomen — Paco Rabane dresses, sunglasses, Polaroid cameras, and so on, all things whose acquisition her husband, an auto mechanic and radio ham, cannot guarantee her.

As for Made in USA, it is the Ben Barka affair, revised and corrected by Dashiell Hammett and Apollinaire, with Anna Karina in the role of Humphrey Bogart and Godard in the role of Howard Hawks. Comes the dreaded moment, the instant of the choice that Godard — not without masochism - imposed on us to make when he decided to shoot two films at the same time and to show them one after the other. Thus his victory will be his defeat and his defeat his victory. While Two or Three Things is at its origin a news item, Made in USA is drawn from a political assassination. Let us call to our aid Roland Barthes, who enlightens us on the difference between these two terms; the political assassination is always by definition a partial fact that refers necessarily to a situation existing outside it, before it, and around it: politics. The current event, on the contrary, is a total, or more exactly, an immanent piece of information. It refers formally to nothing other than itself.

But here is Godard reversing this rule scandalously; Made in USA keeps a structure tragically closed, while the current event of Two or Three Things, which ought to have derived its beauty and its meaning—an immanent entity resolving itself into its immediate données— from itself, opens like one of those strange and ineffable flowers of dreams or of hallucinations, which never stop blooming, disclosing in their petals new existences, new vegetal contexts, unpredictable as the resonance that they were brooding over, the things it signifies and their dream duration is unforeseeable.

Now, Made in USA, a political film, a traitor to politics, paralyzed in its great freedom by an ideological conformity, its colors fading from the very fact of the magnificence of their enamels — never in cinema have reds, blues, greens, been so red, so blue, so green, and everything seems true to Atlantic City — which, like Alphaville, should have resembled Paris and on the contrary resembles Atlantic City really too much, just as the “toughs” who should have made one think of Franco-Moroccan gorillas are, more or less in spite of Godard, too "tough” and in the end are only "toughs" — and yet, Made in USA, — the one that I like the less of these two films because it is too Godardian to be able to be really good Godard, here it does have unexpected events, very violent starts, that shake its entire armature; then, its structure recomposes itself, strengthens itself again, becomes enclosed, anti-Godardian. I was alluding to the deaths of the minor characters whom Godard has Anna Karina kill, and which are the sublime moments of the film.

It is as if the old man with the odd Eastern accent, or the writer who is Belmondo's double or the parallel policeman, existed first of all thanks to the bullets that they encounter. Thanks to their blood, and thanks to Karina, who, after having fired, addresses long looks of comfort to them. Godard makes them live in making them die, one by one, and, to end with, we are encircled by these poetic deaths of minor characters.

But it was with Two or Three Things I Know About Her — "her," this is the moment to say it, is not Marina Vlady, but Paris — that I really felt the pleasure of Godard’s "vulgarity." I call “vulgarity" his capacity, his aptitude, to live from day to day, close to things, of living in the world as do journalists, who know how to arrive on events at the right time, and pay for this punctuality by necessarily undergoing the effects even of the most trivial, like the duration of a match flame. This "vulgarity" is to be a little too attentive to everything, and for that we are deeply grateful to Godard. It is for us that he risks that, because it is to us and for us that he speaks directly, to help us, men existing around him, and that is why it seems that he addresses himself always to someone who is very near him and not to eternity. Thus a monolithic current event, like that of Two or Three Things I Know About Her, which could be extinguished in itself, becomes "means," "vehicle,” of a discourse that concerns us all. The prostitution of the women of the housing developments is only the pale reflection of the prostitution to which we have all, more or less differently, adapted ourselves, but with less innocence than Marina Vlady with her animal, peasant gentleness.

This new Godard full of anger and pity at the same time makes a single gesture and embraces innumerable souls, who are behind innumerable windows of suburban buildings and whom no one would mourn if floods or the bomb were to cross them out of the world forever. The light becomes pink and blue on the resonant partitions of the low-rent apartments; It is a light that we know already, and that resonates familiarly in us; it is the sun of work days, Wednesday or Thursday, in colonies that do not know that they are colonies (in Made in USA, I had forgotten to Say so, everything seems to happen between ten o'clock in the morning and six o’clock in the afternoon one Sunday in July, the bistros almost deserted, boredom for whoever remains in the city).

During this time someone speaks alone in the next room, and the walls are so thin, that everything that he says reaches us distinctly, like the words of the priest behind the grating of the confessional. It is Godard who speaks a monologue in a low voice. like a speaker operated on for cancer of the throat, and who says the rosary of his reflections on cinema and cinematographic style, questions himself and answers himself, protests, suggests, speaks ironies, explains to us that the shots, whether they are fixed, panoramic or dollied, are autonomous, with an autonomous resonance and an autonomous beauty, and that one must not preoccupy oneself too much with foreseeing a montage, for in every way the order is born automatically starting from the moment when we put one shot after the other, and that ultimately one shot is worth as much as another (Rossellini knows that), that if they are charged with poetry, the relationship will be born in spite of everything... and when his extraordinary moral discourse is seized with a slight shaking — and that often happens — it is as if the presentiment of a tragedy were assailing us; the characters of Two or Three Things I Know About Her will end their day with death, or by turning off the lamps by their beds, either ending not making much difference.

May 1967

FILM

FILM  Monday, July 31, 2017 at 8:02AM

Monday, July 31, 2017 at 8:02AM

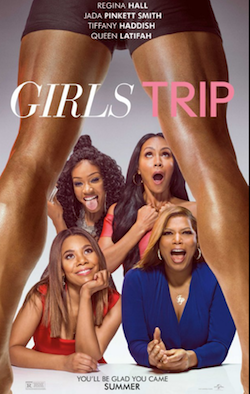

Ryan (Regina Hall) gives out two lectures at the beginning of Girls Trip. The first is to her white assistant Liz (Kate Walsh) who uses a lot of African-American slang and buzzwords around her boss. Since they will be spending the weekend at the Essence Festival in Louisiana, she warns Liz to stop saying these racist things, since she will be around people who might be offended by them. Liz accepts her admonition, while saying farewell to Ryan by stating, "Girl, bye."

Ryan (Regina Hall) gives out two lectures at the beginning of Girls Trip. The first is to her white assistant Liz (Kate Walsh) who uses a lot of African-American slang and buzzwords around her boss. Since they will be spending the weekend at the Essence Festival in Louisiana, she warns Liz to stop saying these racist things, since she will be around people who might be offended by them. Liz accepts her admonition, while saying farewell to Ryan by stating, "Girl, bye."