FILM

FILM In Which Howard Hughes Felt Overly Constipated

Thursday, February 23, 2017 at 10:10AM

Thursday, February 23, 2017 at 10:10AM

Desert Inn

by ALEX CARNEVALE

Rules Don't Apply

dir. Warren Beatty

127 minutes

In the last year of his life, Howard Hughes focused his efforts on two of his favorite pastimes: taking drugs and watching movies. His two most important drugs were Valium and a laxative called Surfak, and he took them both in incredible quantities. In order to relieve constipation, you were supposed to take maybe one Surfak over the course of a day or two. Hughes would take ten or twenty over that period. His prostate gland swelled to over three times normal size. His kidneys shrank in fear.

In the last year of his life, Howard Hughes focused his efforts on two of his favorite pastimes: taking drugs and watching movies. His two most important drugs were Valium and a laxative called Surfak, and he took them both in incredible quantities. In order to relieve constipation, you were supposed to take maybe one Surfak over the course of a day or two. Hughes would take ten or twenty over that period. His prostate gland swelled to over three times normal size. His kidneys shrank in fear.

There is something sad about going out this way, Warren Beatty displays in Rules Don't Apply, his sensitive and entertaining depiction of Hughes' final years on earth. But there is also something very hateful about Howard Hughes that Beatty generally avoids putting his finger on, maybe because he tasks himself with playing the role of the reclusive scion.

Hughes watched the same movies again and again. In particular he watched Bulldog Drummond pictures repeatedly, over the course of several days. He also liked mysteries, even when he knew how they ended.

Frank Forbes (Alden Ehrenreich) becomes a member of Hughes' management team. In Hughes' inner circle, none of these "executives" had any authority over each other, and all were granted a great deal of leeway in how they interpreted the man's instructions. Starting his work for Hughes as a driver, Frank meets Marla (Lily Collins), one of Hughes' contract actresses and drives her and her mother (Annette Bening) around in Hollywood, where they have never been.

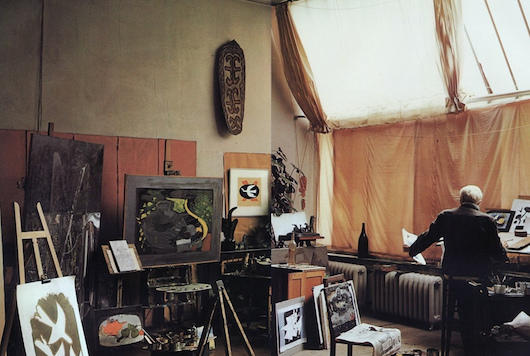

In what is perhaps the most direct tribute to his film's subject, Beatty spent a great deal of money recreating the place in Rules Don't Apply. In the course of funding the project, Beatty has taken on an improbably large coterie of producers. An astonishing sixteen people, including the current Secretary of the Treasury, are credited as producers on Beatty's film, in what might be a warped commentary on the way Hughes did business. Hughes excelled in one-on-one conversations where he could convince people to do what he wanted. It cannot have simply been money or power which accounted for his influence on individuals.

Rules Don't Apply depicts Hughes in the best possible light considering the facts: here he is merely a crazy nut with a heart of gold. The real Howard Hughes was contemptuous of black people and an incredibly unethical and mostly ineffective businessman with some strokes of genius. His personal relationships were few. A long scene in Rules Don't Apply occurs when Hughes finds Marla drunk and waiting for him in a bungalow. He has been informed that to protect him from being declared an invalid as part of an airline deal, it would be better if he were married. So he proposes to the first woman he sees, and they have sex on the couch.

Ehrenreich's character of Frank Forbes loses his admiring view of the boss rather quickly, and the preternaturally talented actor shows every disillusionment on his face. It takes Frank Forbes until the end of Rules Don't Apply to realize that Marla had sex with Hughes and bore his child. Once he does understand that, he forgives her and spends the rest of his life with her. I mean, it was Howard Hughes, what else could she do? Ehrenreich's chemistry with Lily Collins is so insanely exciting that I wish the entire movie had been them talking to each other with no Howard Hughes. Then again, Howard is supposed to be the villain.

After intercourse, the only thing Hughes really retains from the encounter is his promise to give all his contracted actresses their own automobiles. Marla cannot even start hers and, soon afterwards, moves back to Virginia. Frank moves to Las Vegas where Hughes unsuccessfully tried to enter the casino industry for some reason. Rules Don't Apply rarely gives the full context for Hughes' business dealings – it is not that kind of biopic.

Instead Beatty's film focuses on a unique theme – the concept that we know as little about ourselves when we are old as when we are young. Rules Don't Apply faithfully depicts Hughes' notorious aversion to children. Hughes once wrote a several page memorandum to evict an annual Easter Egg Hunt from his casino in abject fear of the damage they might do to the premises. In the final scene of Rules Don't Apply, the son Howard Hughes never actually had watches him sitting in his bed with a small television nearby. "I should really get out more," Hughes announces, and the kid takes his advice.

Certain aspects of Rules Don't Apply remind us of what made the casting and performances of an earlier age in Hollywood so artistically and commerically successful. Beatty is a master at finding the right person for each role, and the cinematography of these familiar environs renders Los Angeles a gorgeous and frightening place. Other particulars of the film's production seem haphazard or rushed – the editing lacks transitions, and short shrift is given to any introspection or continuity.

Instead, we keep returning to this dreary magnate, who alienated almost everyone in his life. We sense that Beatty has met many men like Hughes, who were so wealthy that the only code they were able to live by was that of their own personal preference. Talking to such self-involved individuals, especially when you require their money to pursue your dreams, is a particularly noxious sort of defilement, and depicting it onscreen weirdly justifies it. I loved Rules Don't Apply, but I can't imagine anyone else feeling the same.

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording.