A Way Out

by EMILY ROSENBERG

How we need another soul to cling to, another body to keep us warm. To rest and trust; to give your soul in confidence: I need this, I need someone to pour myself into.

– The Unabridged Journals, Sylvia Plath

So many poetry readers think that Anne Sexton considered Sylvia Plath a rival to her poetic genius. It is tempting to believe something that corresponds so well to the two women’s similar poetry about the darker, feminine experience of the American dream. The truth is, however, that such an unsettling endeavor was hard enough without making enemies.

Readers of modern poetry might as well say that Francis Ford Coppola considered ending his Godfather-fueled reign over American film as soon as he found out Martin Scorsese was making a name for himself in the same genre. This story is, as many movie fans know, also false. But it sounds just as reasonable as the Plath v. Sexton rivalry. The hypothetical Coppola v. Scorsese fight could have run off any tabloid and become a fact for many who would believe the rumor until another flashy piece of written evidence told them it was a lie. The more reasonable story is one that tells how Martin was inspired by Francis’ films, using his people and settings to tell new stories that may not have existed without The Godfather.

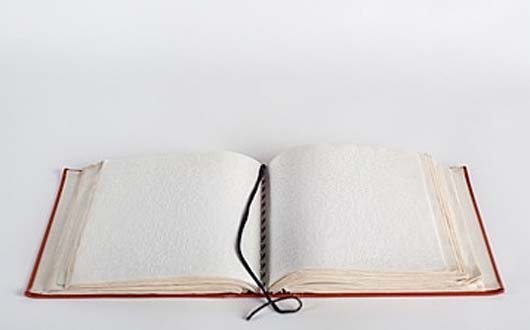

Luckily for Anne and Sylvia, there js enough evidence to prove the rivalry between the two canonical figures of confessional poetry was more like an angry symbiosis. Anne’s 1965 copy of Sylvia’s last poetry collection Ariel looks nothing like what avid believers of mid-twentieth century literary talk would expect. The copy does not resemble a bleeding, marked up semblance of a Normal Mailer draft. The one-way correspondence, reading as a broken-up eulogy from Anne to the dead Sylvia, is more like a college student’s notes on a poet or writer - one whose voice is different, maybe more uncomfortable to digest, than what the student labored over in high school textbooks. The notes, as well as Anne’s more connected eulogy to her friend in “Sylvia Plath,” show that what the women had in common, more than a need to come out on top, was an unavoidable empathy with each other.

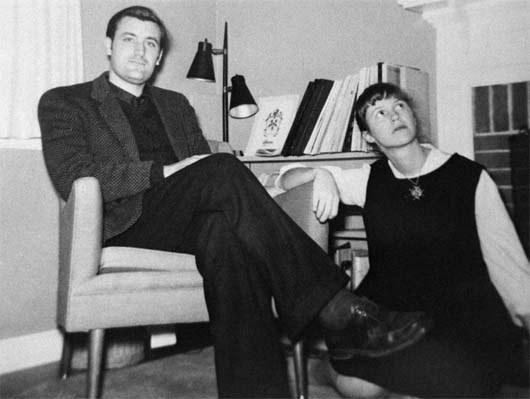

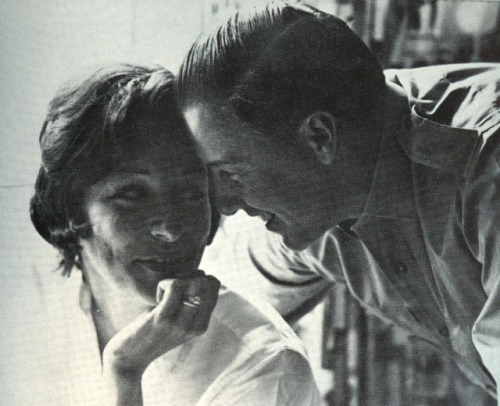

The two poets met at a seminar in 1958, ten years after Alfred Sexton II, who called himself “Kayo,” turned Anne’s pen name from the forgettable Harvey into the Sexton that now accompanies almost any image of a witch in poetry. Anne and Sylvia had much more in common than they thought, from their unavoidable notice of death, to their desire to become poets, to their decision to talk about both over martinis after class at the Boston Ritz-Carlton.

The two always talked about the seminar and its professor, their confessional predecessor Robert Lowell, while downing at least “three martinis,” as Anne remembers. Another student from the seminar, George Starbuck, would often join them for drinks. He could not distract from the bizarre talk spiking the usual yuppie conversation with an unfamiliar idea that could have been almost progressive. What made Anne and Sylvia stand out from their male classmates and professor was their unique, yet mutual, idea that death would make them even freer, even more insightful, than anything else they could find in life.

Anne and Sylvia’s realization that they both had this faith in death increased their closeness and only made the line between male and female poets at the time bolder. Unlike the fondness and nostalgia for traditional, American values that became Robert’s signature, Sylvia and Anne’s view of what these values did to their independence is what almost completely separates them from other confessional poets. They could have been drawing each other into a friendly twofold bet every night at the Ritz, one that would allow them to write about death’s true nature and eventually find it out for themselves. To George or to anyone else in the bar watching, they might have been witches. Even Anne and Sylvia may not have known they were casting irresistible spells on each other, wrapping themselves in natural, sometimes pagan ideas that did not yet have a place in the American life.

Anne had married Kayo ten years before she met Sylvia. They had two children and Anne was smitten with him, even without a complete sense of monogamy, for at least twenty years after she met Sylvia. Their marriage was another way for Anne to show how much her love for a man meant to her, even though the institution of marriage meant little. Anne did not hide her several affairs from her husband, but she didn’t divorce him until only a year before her death. Like Sylvia, who wanted someone to “pour herself into,” Anne needed Kayo to be there, to hear her and be the voice that she could listen to without any degree of repulsion. She admitted to her first psychiatrist Dr. Martin that “when my husband is away, I fall apart.”

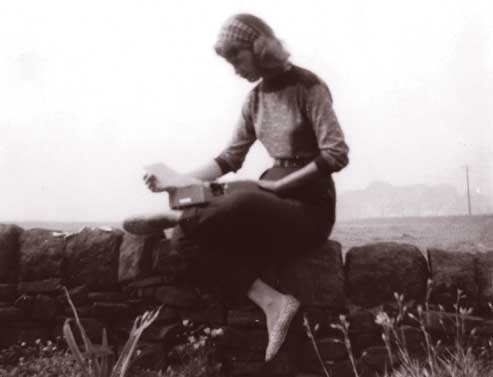

Sylvia started in the same place as Anne in 1956, marrying the British poet Ted Hughes and having two of his children within the next six years. Sylvia fell in love with Ted in Cambridge, Massachusetts at the release party for a magazine that was publishing four of his poems. The night was an ecstatic one for Sylvia. She remembers how Ted was the only man at the party “huge enough” for her. He soon became the only one who could doom her into the marriage that would add a new spark to her poetry.

Nevertheless, Sylvia suffered several periods of writer’s block throughout her time living with Ted and their children in London and Devon, England. Every time her anger with Ted grew strong, she’d break through the writer’s block. After learning of Ted’s affair with their London neighbor Assia Gutmann, Sylvia wrote her most famous poems. She wrote twenty-five more in less than a month once she divorced the openly unfaithful Ted. Perhaps one of the things Anne and Sylvia could not absorb from each other was the idea of love, the lack of it fueling the stories Sylvia’s poems and the overwhelming abundance of it spilling into Anne’s words.

Both men and women in the 1960s likely thought it was strange that Anne and Sylvia wanted to escape the world that Robert, and other male poets like Ted, built for them. Women were also holding onto the faith that theirs wasn’t a world of households, children, and endless bee-like droning during that time. Anne and Sylvia met and wrote in order to tell them that their world included these, but also a way out.

One of these escape routes was the ocean. The ocean was the place where Sylvia and Anne would run into Robert… the same ocean that he thought was supporting his American dream as he stands on a beachside cliff in his less known poem “Castine Harbor.” Robert felt a kind of faith to the ocean. He made it similar to the 1950s to 60s values that made his life as a poet, a husband, a father, and an independent person possible. He goes so far as to make the ocean equal to “God, who must forgive us for having lived.” His guilt is one for the progress of humanity, one that lets people “fly like angels” and leave the foundations of the familiar home forgotten. But Anne, who wants to walk straight into its dangerous waves in “Wanting to Die,” and Sylvia, who realizes in a scene of The Bell Jar that she doesn’t have nearly enough courage to do so, have a different reason to almost worship the ocean. It’s one of the first times that both Anne and Sylvia find something natural that will free them from the household, something that would drown rather than compose itself of the values that stunted what they knew of Robert’s independence. At this coastline, the one between normal, imprisoning life and terrifyingly free death, Anne and Sylvia realized that together, there could be more than one way to dive into what nobody could know for sure.

By underlining and annotating those parts of Ariel that struck her the most, Anne made a blueprint of some things she learned from Sylvia, as well as other things that Sylvia learned from her. It would be hard to remember Anne’s poem “Her Kind” without including the image of the “possessed witch” who “waves her nude arms at villages going by”… the one that stops moving so fervently when Anne leaves her “arms stretched out to that stone place” where she knows Sylvia will always live in “Sylvia Plath.” That witch is the same one who takes “the skillets, carvings, shelves, closets, silks, innumerable goods,” so familiar to Sylvia in her kitchen and basement, and turns them into a sorceress’ tools. They please the ones she has to look after as a mother and a wife, but they can also be the tools of a witch… a woman who Anne was at one point, who wouldn’t have been afraid to walk into the ocean if it were facing her. The idea that an escape could be as natural as the ocean, but that one needed bravery as supernatural as witchery to face it, made dying an available challenge. Its attainability, however, was impossible for her to doubt, especially when Sylvia looked at nature and the woman in the same way.

The supernatural bravery of the woman in Sylvia’s poetry is not of a witch figure like the one of Anne’s dark, female-centric fairy tales, but it grows out of a similar isolation from others that seems almost pagan. Like the witchy Anne in “Her Kind” who retires to “warm caves” in the woods, Sylvia wanders away from neighbors and loved ones into the woods in the poem “The Moon and the Yew Tree.” She writes in her diary that she constantly remembered feeling the intoxicating, almost intimidating energy of the moonlight whenever she walked through the woods to visit her father’s grave. She made the graveyard a common sight in her poems and a constant presence in her own life, perhaps to make up for the nineteen years she refused to visit her father’s grave after his death.

You would think the graveyard would be a place to rekindle Sylvia’s loyalty to her father. Iinstead it becomes a haven for other non-human spirits of the world. The feminine moon in the poem is the only female figure that does not let masculinity hold her back. She is as “bald” as the “nude arms” of Anne when she was a witch. She is unashamed to be “wild” like the witch who has few fears and even less self-consciousness. One of the more heavily marked poems in Anne’s copy of Ariel, “The Moon and the Yew Tree” would have been a dark world without a moon had Sylvia not been able to see Anne writing and finishing “Her Kind.”

Whether or not one did better than the other, Anne and Sylvia couldn’t avoid becoming friends once they both became poets. They were the ones who could turn the thoughts of their contemporary house-bound American women into a story when others before them could not. They knew that every housewife was different before her marriage. They also knew how their thoughts could take either a submissive or a resistant path away from the droning work they were doing every day. Anne and Sylvia were the ones who wanted to resist, even though during their friendship it seemed like their story would have the same ending as every other woman’s story did. They’d put their sons into the world and their daughters into a house, and die in the happiest, most natural way they could as old, compliant women. But Anne and Sylvia, knowing they couldn’t venture back to the girlish independence that died in their twenties, decided it’d be best to escape to the only place without age.

Before they could court death with lone witches and living moons, Anne and Sylvia met in poems about men, but their ideas did not crash into each other. Sylvia’s most well-known poem about men, “Daddy,” did not take form until she met Anne’s poems on the men in her life. Anne’s poem from 1959, “My Friend, My Friend,” takes on the chanting, accusatory “you” rhymes that those who remember “Daddy” cannot forget. The idea that Sylvia might be a Jew also comes from “My Friend, My Friend,” when Anne gives up her “calm white pedigree” in favor of something she doesn’t even know.

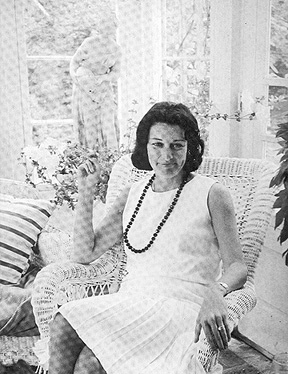

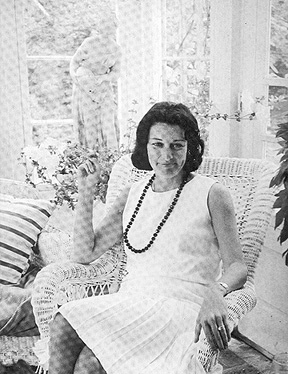

Anne tried to escape from her life, especially from the people in it, several times. Nobody could, or wanted to, understand why. Anne started attempting her escapes even before she was writing poetry, when she was twenty-eight and had been a housewife for almost ten years. It was her first psychiatrist, Dr. Martin T. Orne, who told her that writing poetry might be a good path for her, one that would let her stay in the world a little longer if it couldn’t entirely cure her from insanity.

By the time of her first visit, Anne had already started some of what her family remembers were her signature ticks. Her daughter remembers Anne moving her eyes up and down a wall every night after dinner, widening them as if she were expecting it to do something for her. For “Dr. Martin,” her mental instability was a sign of her creative potential, but for anyone viewing her without a psychological perspective, she was showing more signs of a destructive potential. Her first way to escape with a pill overdose only spawned new ways, even after she started seeing Dr. Martin and writing poetry. Anne tried to find new ways to leave the world, sometimes in a car filling itself with carbon monoxide, and other times just by staying at home to try the first route with pills again.

The attempts constantly brought her back to Dr. Martin and poetry. After only three months of therapy with him, Anne wrote her first collection of poetry, To Bedlam and Part Way Back. The collection more than anything else was “frank,” as Anne’s other poet friend Maxine Kumin called it. The directness of its words seduced women of 1957 into thinking that their anger was more normal than anyone wanted to admit. It had sent one of them into a prison of self-doubt, psychiatric therapy, and constant plans to escape it all. But it had also sent that same woman into fame, admiration from thousands of American women, and a hyper-sexuality that made Anne more dependent on the world than she would have ever liked to think.

The sessions with Dr. Martin led Anne to do more with her energy than write poetry. She’d had affairs with several men, including her second psychiatrist who she called “Dr. Zweizung,” as well as one woman. Her open sexuality, and her lack of an effort to hide her affairs from Kayo, came as a little surprise for someone who wrote about masturbation, menstruation, incest, abortion, and rape almost as much as death in her poetry. Anne’s need to “sexualize everything” in her sessions and in her poetry, as Dr. Martin noted, was something that Sylvia, although not nearly as sexually liberal as Anne, could understand. The stories about sex, as vulgar as they were, in Anne’s poetry did not come only from her own mind. They were a mixture of several men, from her psychiatrists to Kayo to her own father, that was more taboo but just as dark as the men in Sylvia’s poetry.

Both women thought that death could be a good escape from the madness that men provoked in them. Sylvia’s “Daddy” takes this idea to its zenith. Although she borrows the idea that “might as well be a Jew” from “My Friend, My Friend,” Sylvia’s anger at her “Aryan” father, “the man in black,” is all her own. To Sylvia he is “not God but a swastika, so black no sky could squeak through.” He is the man who betrayed not only his family but the entire world with his sympathies for Nazi Germany. His support for the mass murder of Jews echoes in Sylvia’s words, those same words giving in to the unconquerable power that Ted wielded over her poetry and her life. Anne’s notes on the infamous “Daddy” drip with the same anger that Sylvia felt when she looked at the protective glance of the father that she could not trust – the glance that Anne wrote she could see “devour” Sylvia “in a single glance.” Just like the cult-like group of readers that identified with Anne’s poetry, Anne reached out to Sylvia’s words about her father as a traitor instead of a guardian.

Anne talked often in her sessions with Dr. Martin about her own father’s molestation of her, something that fascinated her as an adult and took a dark form in her own molestation of her daughter Linda. Like Otto, Anne’s father was the first man who made Anne find that domestic life was not a free one, not even a good one. Even though Sylvia took Anne’s rhymes and ideas from “My Friend, My Friend” and turned them into a near-canonical American poem, Anne’s note in Ariel makes it clear that she couldn’t be angry now that, finally, another woman’s innermost anger was in print.

Anne may have appreciated “Daddy” in her notes because Sylvia was able to tell a story in it that transitioned from a girlhood of short poems and essays to a womanhood of dark, now famous poems that partially grew out of Anne’s own words. Otto Plath was the first of two major male influences on Sylvia’s poems. A German immigrant and biology professor, Otto first disturbed his daughter with an unmanageable gangrene infection in his foot that, as something he ignored, took him away from her life when Sylvia was eight years old. She loved him very much as a child, swearing that “she’d never speak to God again” after he died. She only started to despise him for his sympathy with the Nazis after his death.

She waited much less to address the second man she loved… the one who catapulted her name with his own before “Daddy, you bastard, I’m through” became one of the signature lines of female rage. Even with these now-famous words, Anne’s copy of Ariel shows how Sylvia’s work could not exist without some amount of regards for her husband Ted, whose reviews and accolades star one of the book’s cover flaps.

Ted was the man who publicly discussed Sylvia’s neurosis surrounding her writing, her father, her marriage, and her death. He even burned some of her diaries after he inherited her estate, claiming in one interview that he didn’t want his children to read about what she was feeling and thinking during her last days. Ted didn’t know that these acts would earn him another ironic reputation that connects itself to Sylvia rather than his poetry. After years of writing her most angry and famous poetry, yet remaining the caretaker of Ted’s children, Sylvia committed one of the most famous suicides in history by locking herself in the kitchen and sticking her head into its running gas oven. She escaped the world while her children ate lunch in the next room.

Before Sylvia’s escape, Ted had already married his mistress Assia Gutmann, who had moved into the family’s house in Devon. She spent seven years sleeping in what was once Sylvia’s bed, using perhaps the appliance or household good that Sylvia might have been hesitant to open in “A Birthday Present.” In a tragic, ironic twist that Ted may have only predicted in a nightmare, Assia locked both herself and their daughter “Shura” in the kitchen with a running oven, following Sylvia to her freer existence. Assia, even if she took the monogamy away from what was still a conventional marriage, needed to escape from her stifling marriage to Ted just as much as Sylvia did. The combination of Ted’s continuous affairs and Sylvia’s words constantly running through English presses was enough to make her listen to the wife who was in the house before her. Nothing could have convinced Ted more that Sylvia’s words said something about being a woman at the time that his could not.

Listening to some words from Kayo, who remained Anne’s husband for almost twenty-five years, may have helped Ted realize how Sylvia never wrote anything alone. “Daddy” exists because Sylvia listened to words from Anne and felt the anger that grew out of her discoveries about Otto and Ted. Anne must have agreed with her own words as well… neither she nor Sylvia had a “special legend or God to refer to.” Everything from the pagan life they give to the moon and the trees, and the human anger that men constantly hurled onto them, were all a part of the world. These qualities were not there only poetic devices. They were undoubtedly real, pushing Anne and Sylvia more and more towards the freedom they deserved but could not receive, even in the poetry field that now defines one of its time periods with their voices.

Unlike their mentor Robert Lowell, who combined the roles of father and writer with invisible seams, Sexton and Plath tried repeatedly to rip apart the nightmare that the American dream had become for them. After writing the enraged, revolutionary words that would shine an uncomfortable new light on American femininity, Sylvia was the first to gas her voice into a much quieter death in 1963. Anne was left without one of her greatest friends, but she toasted the death, the one she “drank to” with Sylvia at the Ritz, as well as “the motives and the quiet deed” itself. These words from “Sylvia Plath” and the notes in her copy of Ariel were some of Anne’s last gifts from her lost friend.

On October 4th, 1974 Maxine Kumin was having lunch at Anne’s house to talk about Anne’s latest and last collection with the intentional title of The Awful Rowing Toward God. At some point in the afternoon, Anne excused herself from the room to put on her fur coat, proceeded to the garage, turned on her car engine, and asphyxiated herself on the carbon monoxide she’d flirted with so much throughout her years of psychiatric sessions, occasional psychiatric affairs and consistently frank poems.

Neither poet stayed too close to the obvious images, both wild and domestic, that haunted their shortened lives. Honey, and the manmade Tate and Lyle substitute that became too familiar for their housebound lives, was one of the less memorable but more disorienting features of their poetry. Not as grand as the moon but more intense than a description of their actual families could be, the artificial sweetener is something that women still face every day. It is more economical than honey and less fattening than sugar… it’s still the ideal standby sweetener for the ideal woman. In Sylvia’s “Wintering,” honey becomes simply interchangeable with the artificial sweetener of the day. Whatever she uses, it will put her in the droning role that female bees take on as they usher honey between different chambers of the hive.

Neither poet stayed too close to the obvious images, both wild and domestic, that haunted their shortened lives. Honey, and the manmade Tate and Lyle substitute that became too familiar for their housebound lives, was one of the less memorable but more disorienting features of their poetry. Not as grand as the moon but more intense than a description of their actual families could be, the artificial sweetener is something that women still face every day. It is more economical than honey and less fattening than sugar… it’s still the ideal standby sweetener for the ideal woman. In Sylvia’s “Wintering,” honey becomes simply interchangeable with the artificial sweetener of the day. Whatever she uses, it will put her in the droning role that female bees take on as they usher honey between different chambers of the hive.

For Sylvia, honey is more of a trap than a kind of natural sugar. It threatens Plath’s independence and reinforces marriage. Like the poems on Otto and Ted, these poems on the droning modern woman is what attracted Anne’s pen the most in her copy of Ariel.

In “Sylvia Plath,” Anne remembers Sylvia as devoted to these daily tasks of “raising potatoes and keeping bees,” the meaningless ones that somehow became important when they became part of poetry. Even for the poet trapped in the role of a wife and mother, honey is better than Tate & Lyle. What could be less threatening to a woman’s creativity and her own words than honey? Even as a household object, it somehow feeds the creativity that we may have thought mundane life had killed. Anne and Sylvia’s words have become honey for me. If I stick onto them, even if I let go of myself and feed off of what they have already written, I might be able to escape whatever bothers me for a little while. But without their words, I never would have found those cracks in the wall of the world that sometimes seems, as Sylvia feels in “Wintering,” to be “without a window.”

Emily Rosenberg is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Atlanta. She last wrote in these places about Russia. You can find her website here. You can find her twitter here.

"Organized Scenery" - Au Revoir Simone (mp3)

"Shadows" - Au Revoir Simone (mp3)

POETRY

POETRY  Friday, February 27, 2015 at 11:45AM

Friday, February 27, 2015 at 11:45AM