FILM

FILM In Which Thieves Highway Never Ends

Saturday, August 8, 2009 at 10:46AM

Saturday, August 8, 2009 at 10:46AM Up the Pacific Coast

by ELEANOR MORROW

The perfect movie is Ozu's Tokyo Story, but second and an unassailable classic is Jules Dassin's Thieves' Highway. It takes one of the more boring premises — running apples up the coast to San Francisco in a rickety truck — and makes it into the highest art imaginable.

Nicky is home to visit his parents back from the war where he expanded American democracy, the loyal son of Greek immigrants. He finds out that a big stiff named Mike cheated his father out of a litter of tomatoes and left him paralyzed by the end of it. Nick's ma doesn't know what to believe, but Nicky knows better. He is determined to take revenge for what happened to his family.

As you might have guessed, with respect of the America of Thieves' Highway we might as well be de Tocqueville. It is us looking in on the confluence of these generations of immigrants. Nicky's parents are of the first generation; he's fully Americanized and yet the dilemmas he faces are as old as the Polish ghetto. He's ostensibly in love with a prim, blonde white girl, until he finds he isn't in love with her at all.

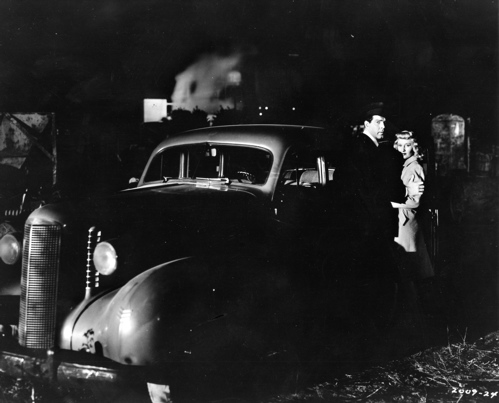

A revenge story is always the best cinematic medicine. Instead of doing a film of characters talking to each other, Dassin does a film in which they're all over each other. Once he hits San Francisco while almost getting crushed underneath his truck in the process, Nicky runs into the wrong end of the short con, meeting a foreign woman, about whom he only knows that she is cheating him somehow. She is the opposite of his plain Jane whitebread California valley girl, maybe the first real Valley Girl.

In one scene Nicky's fiancee Polly happens on what's become of him in one trip up to San Francisco. She appraises her bruised boyfriend, who has by virtue of his naivete been tossed around the city. She says, "I don't suppose you even have enough money to send me home, do you?" California girls are all the same. They have high standards, and they always expect disaster.

Nicky barely seems bothered by his development. Revenge owes no obligation to the vicious subtleties of romance. Nicky is given the illusion of choice...he is offered up to an enterprising young white woman, only to end in the arms of someone a little more his speed. She can barely pronounce his name, but to bang a con artist is a singular thrill. He allows her to take him into her arms, and while he does, her boss starts stealing Nicky's apples. You can't do that. He rises up at the man who is trying to defile him. In this loving gesture we feel the excess fury of his demand for what is right.

These broad strokes are perhaps touched on better in genre films than in so-called artistic films. Dassin fused them together, later making art out of a heist movie in Rififi. Dassin was a master filmmaker who got on the Hollywood blacklist. He had to relocate to France, a bizarre fate for a Jewish-American born in Middletown. (Our history with the Jews is more complex than even Abraham Foxman would have you believe.)

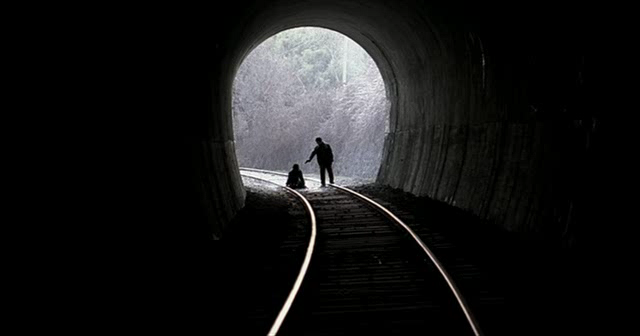

The emotional center of Thieves' Highway is actually an action scene. The major subplot of the film concerns Nicky's partner in the apple-toting enterprise, a crackfaced white guy trying to get along in a world of crooks. "You've got to be canny in this business," he tells Nicky, who obviously wasn't listening. The guy is driving down a road when his driveshaft conks out and his shaky truck explodes into a fiery ball.

The field he lies on is coated with burnt apples, some of them salvageable. He dies with no one to remember who was and how he had tried.

People crowd the road to get a better view of the dramatic accident. It is one of the most beautiful action sequences ever in film, and it happens to be one of the first. Before Duel this chase meant more. The act of witnessing is a profoundly American trait, of looking on, of taking notice of the small injustices and putting them right.

Thieves Highway is just as memorable because remarkably little of our cinema discusses what it took for America to become America. Books and even radio remember the past, the cinema forgets it. It's easier to simply construct a more modern set, with characters and people of the time who might seem more relatable. The past is a strange brew, and even Dassin might suggest, in the blood wake that ensues here, that we are better rid of it.

Eleanor Morrow is the senior contributor to This Recording. She tumbls here.

"Circus Song" — The Great Book of John (mp3)

"Echoing Laughter" — The Great Book of John (mp3) highly recommended

"Death of a Middle School Guidance Counselor" — The Great Book of John (mp3)