BOOKS

BOOKS In Which Writing Is Uncomfortable At A Round Table

Thursday, December 2, 2010 at 10:56AM

Thursday, December 2, 2010 at 10:56AM

Why, How to Write

This is the third of a four part series of writers on writing. Once I had a writing teacher who told me that he couldn't respect anyone whose work he didn't like. I told him I couldn't like anyone's work who I didn't respect, but I was lying, since I spent most of yesterday reading ABC of Reading. Still, we try to keep this space anti-Semite free and I have a long essay in the works about why The BFG ruined 1991 for me. The best writing advice implores you to see if you can work around it, but some of what you read below is actually valuable. Generally, the more practical advice seems at the moment of its imparting, the less relevant it will actually become. Please revisit the first two parts of this series below:

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

W. Somerset Maugham

All I can usefully do is to tell you what is my own practice, and the first thing that strikes me that I have no habitual practice; it seems to me that every novel must be written in an entirely different fashion, and so far as I am concerned each one is in a way no more than an experiment. Each subject needs a different treatment, a different attitude, and even a different manner of writing. The only rule I know which is always valid is to stick to your point like grim death.

I cannot help thinking that to entertain is sufficient ambition for the novelist, and it is certainly one which is hard to achieve; if he can tell a good story and create characters that are fresh and living he has done enough to make the reader grateful. You will not have failed to notice that many novels are written which have every possible excellence and yet are quite unreadable. I hope you will not think it a willful eccentricity when I tell you that I look upon readableness as the highest merit that a novel can have. They say it is better for women to be than to be clever; that is a point upon which I have never been able to make up my mind; but I am quite sure that it is better for a novel to be readable than to be good and clever. I have often wondered what exactly it is that gives a book this quality. I will not tell you all the conclusions I have come to but only one or two points which seem to me to tend to that admirable result.

I think first of all that the writer is wise to be brief. The value of a piece of fiction depends in the final analysis on the personality of the author. If it is interesting, he will interest. It is true that the young writer cannot expect to have a personality that is either complex or profound; personality grows with the experiences of life; but he has some counterbalancing advantages. He sees things, the environment in which he has grown up, with the freshness and energy of his youth; he knows the persons of his own family and the persons with whom his daily life since childhood has brought him in contact, with an intimacy he can seldom hope to have with people he comes to know in later years. Here is material ready to his hand. If his personality is so commonplace that he can see this environment and these people only in commonplace way, then he is not made to be a writer, and he is only wasting his time in trying.

Langston Hughes

How to be a bad writer (in ten easy lessons):

1. Use all the clichés possible, such as "He had a gleam in his eye," or 'Her teeth were white as pearls."

2. If you are a Negro, try very hard to write with an eye dead on the white market - use modern stereotypes of older stereotypes - big burly Negroes, criminals, low-lifers, and prostitutes.

3. Put in a lot of profanity and as many pages as possible of near pornography and you will be so modern you pre-date Pompeii in your lonely crusade toward the bestseller lists. By all means be misunderstood, unappreciated, and ahead of your time in print and out, then you can be felt-sorry-for by your own self, if not the public.

4. Never characterize characters. Just name them and then let them go for themselves. Let all of them talk the same way. If the reader hasn't imagination enough to make something out of cardboard cut-outs, shame on him!

5. Write about China, Greence, Tibet or the Argentine pampas — anyplace you've never seen and know nothing about. Never write about anything you know, your home town, or your home folks, or yourself.

6. Have nothing to say, but use a great many words, particularly high-sounding words, to say it.

7. If a playwright, put into your script a lot of hand-waving and spirituals, preferably the ones everybody has heard a thousand times from Marion Anderson to the Golden Gates.

8. If a poet, rhyme June with moon as often and in as many ways as possible. Also use thee's and thou's and 'tis and o'er , and invert your sentences all the time. Never say, "The sun rose, bright and shining." But rather, "Bright and shining rose the sun.'

9. Pay no attention really to the spelling or grammar or the neatness of the manuscript. And in writing letters, never sign your name so anyone can read it. A rapid scrawl will better indicate how important and how busy you are.

10. Drink as much liquor as possible and always write under the presence of alcohol. When you can't afford alcohol yourself, or even if you can, drink on your friends, fans, and the general public.

If you are white, there are many more things I can advise in order to be a bad writer, but since this piece is for colored writers, there are some thing I know a Negro just will not do, not even for writing's sake, so there is no use mentioning them.

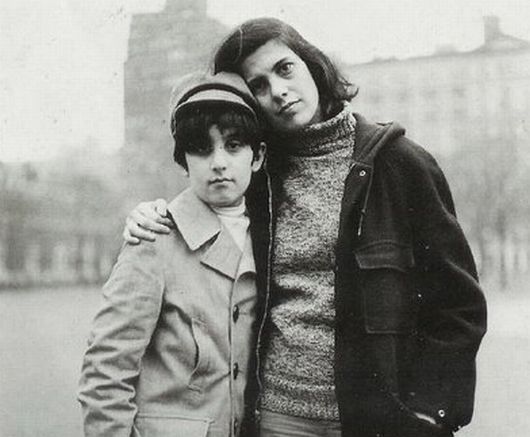

Marguerite Duras

It's uncomfortable sitting at a round table: your elbows aren't resting on anything and you can't lean on them to rest from writing, and while you're writing they're sticking out into nowhere, and if you don't notice that right away you tell yourself, "I don't know what's wrong with me, I'm tired," and it's because your elbows aren't resting on the table.

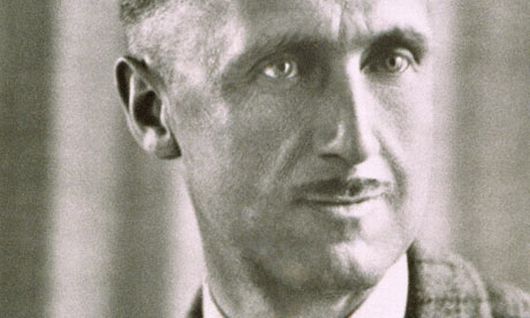

George Orwell

Putting aside the need to earn a living, I think there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose. They exist in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living. They are:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all — and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose. Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

It can be seen how these various impulses must war against one another, and how they must fluctuate from person to person and from time to time.

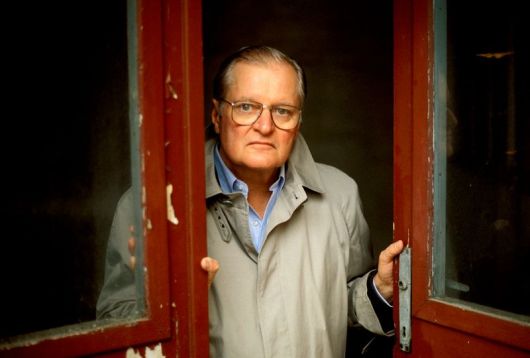

John Ashbery

Every writer faces the problem of the person that he is writing for, and I think nobody has ever been able to imagine satisfactorily who this “homme moyen sensuel” will be. I try to aim at as wide an audience as I can so that as many people as possible will read my poetry. Therefore I depersonalize it, but in the same way personalize it, so that a person who is going to be different from me but is also going to resemble me just because he is different from me, since we are all different from each other, can see something in it. You know — I shot an arrow into the air but I could only aim it. Often after I have given a poetry reading, people will say, “I never really got anything out of your work before, but now that I have heard you read it, I can see something in it.” I guess something about my voice and my projection of myself meshes with the poems. That is nice, but it is also rather saddening because I can't sit down with every potential reader and read aloud to him.

I write on the typewriter. I didn't use to, but when I was writing “The Skaters,” the lines became unmanageably long. I would forget the end of the line before I could get to it. It occurred to me that perhaps I should do this at the typewriter, because I can type faster than I can write. So I did, and that is mostly the way I have written ever since. Occasionally I write a poem in longhand to see whether I can still do it. I don't want to be forever bound to this machine.

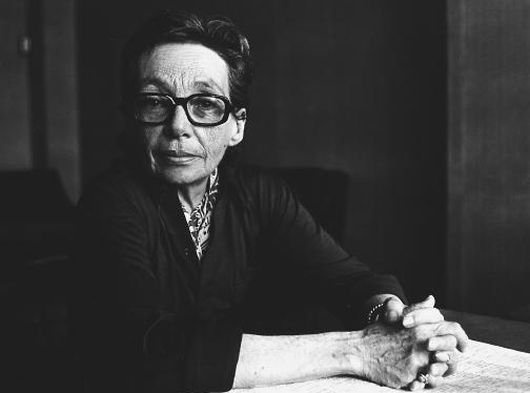

Susan Sontag

Many writers who are no longer young claim, for various reasons, to read very little, indeed, to find reading and writing in some sense incompatible. Perhaps, for some writers, they are. It's not for me to judge. If the reason is anxiety about being influenced, then this seems to me a vain, shallow worry. If the reason is lack of time — there are only so many hours in the day, and those spent reading are evidently subtracted from those in which one could be writing — then this is an asceticism to which I don't aspire.

Losing yourself in a book, the old phrase, is not an idle fantasy but an addictive, model reality. Virginia Woolf famously said in a letter, ''Sometimes I think heaven must be one continuous unexhausted reading.'' Surely the heavenly part is that — again, Woolf's words — ''the state of reading consists in the complete elimination of the ego.'' Unfortunately, we never do lose the ego, any more than we can step over our own feet. But that disembodied rapture, reading, is trancelike enough to make us feel ego-less.

Like reading, rapturous reading, writing fiction — inhabiting other selves — feels like losing yourself, too.

Everybody likes to think now that writing is just a form of self-regard. Also called self-expression. As we're no longer supposed to be capable of authentically altruistic feelings, we're not supposed to be capable of writing about anyone but ourselves.

But that's not true.

Robert Creeley

For me, it's literally the time it takes to type or otherwise write it — because I do work in this fashion of simply sitting down and writing, usually without any process of revision. So that if it goes — or, rather, comes — in an opening way, it continues until it closes, and that's usually when I stop. It's awfully hard for me to give a sense of actual time because as I said earlier, I'm not sure of time in writing. Sometimes it seems a moment and yet it could have been half an hour or a whole afternoon. And usually poems come in clusters of three at a time or perhaps six or seven. More than one at a time. I'll come into the room and sit and begin working simply because I feel like it. I'll start writing and fooling around, like they say, and something will start to cohere; I'll begin following it as it occurs. It may lead to its own conclusion, complete its own entity. Then, very possibly because of the stimulus of that, something further will begin to come. That seems to be the way I do it. Of course, I have no idea how much time it takes to write a poem in the sense of how much time it takes to accumulate the possibilities of which the poem is the articulation.

Allen Ginsberg, for example, can write poems anywhere — trains, planes, in any public place. He isn't the least self-conscious. In fact, he seems to be stimulated by people around him. For myself, I need a very kind of secure quiet. I usually have some music playing, just because it gives me something, a kind of drone that I like, as relaxation. I remember reading that Hart Crane wrote at times to the sound of records because he liked the stimulus and this pushed him to a kind of openness that he could use. In any case, the necessary environment is that which secures the artist in the way that lets him be in the world in a most fruitful manner.

John Steinbeck

My basic rationale might be that I like to write. I feel good when I am doing it — better than when I am not. I find joy in the texture and tone and rhythms of words and sentences, and when these happily combine in a "thing" that has texture and tone and emotion and design and architecture, there comes a fine feeling — a satisfaction like that which follows good and shared love. If there have been difficulties and failures overcome, these may even add to the satisfaction.

As for my "reasoned exposition of principles," I suspect that they are no different from those of any man living out his life. Like everyone, I want to be good and strong and virtuous and wise and loved. I think that writing may be simply a method or technique for communication with other individuals; and its stimulus, the loneliness we are born to. In writing, perhaps we hope to achieve companionship. What some people find religion, a writer may find in his craft or whatever it is — absorption of the small and frightened and lonely into the whole and complete, a kind of breaking through to glory.

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

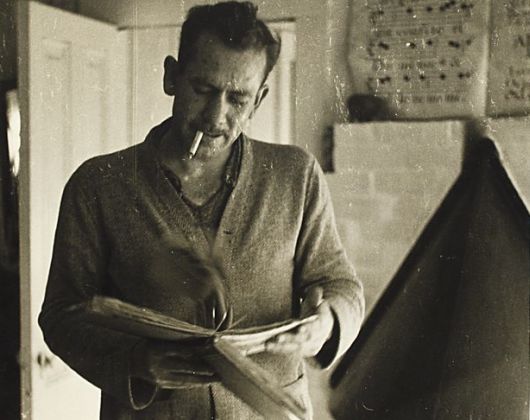

ms. duras

ms. duras

"Ghost of Love" - David Lynch (mp3)

"I Know" - David Lynch (mp3)

"Good Day Today" - David Lynch (mp3)

photo by oliver zahn

photo by oliver zahn