Novel Spending

There is no more careless task in the universe than the giving of a gift certificate. Yet it must be spent on something, ideally before the company that issued it begins reclaiming it bit by bit in a measured attack on consumers around the world. The quicker you spend it on a book, the better you'll feel about yourself. But what book? Taste rules dreams, sexual profligacy and buying power. Haven't you seen High Fidelity? Novels are the ultimate arbiter of taste, for there is truly nothing that they cannot contain under the right circumstances. When we asked this group of writers and editors for their favorite novels, this is all we heard back.

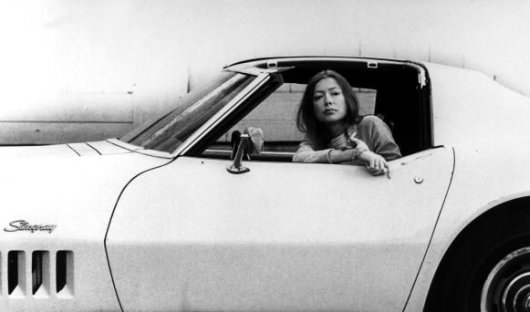

Tess Lynch

In the Lake of the Woods by Tim O'Brien

This is a book about Vietnam. Please, sit down. Come on, it isn't really about Vietnam, it's about – just sit down for one second – the clashing of public and private life, when the demon-like personifications of every horrible thing you've ever done wage war with whatever good parts of you still exist; the plot consciously implodes on itself, leaving you feeling psychologically fractured and with nightmares about killing your houseplants with boiling water while screaming "Kill Jesus," just like you've always wanted.

Chilly Scenes of Winter by Ann Beattie

Ignore the movie please. This was Beattie's first novel, and my favorite of hers, not only because there's a character in it who spends all of her time in the bathtub like I do, and not only because Sam is the fictional hot best friend I projected any and all fantasies onto during my formative years, but because it's a quiet study of the electrically-charged feeling of being in love operative-word-hopelessly. The desserts she cooked that you miss, the radio songs, the happy hour beers spent bumming. Too true, Ann, too true.

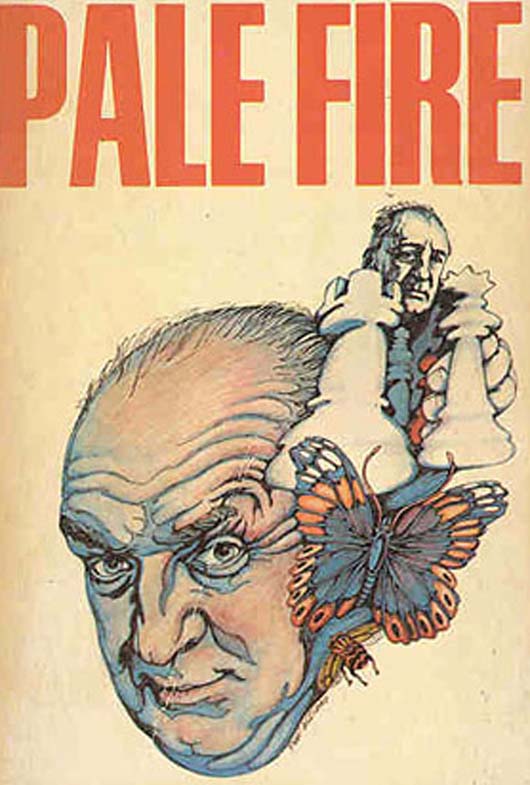

Pale Fire by Vladimir Nabokov

You know what? Fuck Lolita. I take that back, don't fuck Lolita, she's too young, plus I loved that book. I loved this one more, though. The poem makes me disintegrate with feelings. I'd get all 999 lines tattooed on my face, but then I'd never be able to work in corporate America. John Shade's poem can be a bit of a downer ("how many more/Free calendars shall grace the kitchen door?"), so fictional editor Charles Kinbote comes in to offer up some zippy commentary from the imaginary land of Zembla. I thought Kinbote was supposed to make me feel better, that that was his purpose, but apparently Nabokov, in an interview, mentioned that Kinbote killed himself after publishing the manuscript. God, what a downer. I wish I'd never heard that bit of imaginary news; maybe there's no point to anything and I should go ahead and get that tat, do you think it would be pretty sickkk?

The Stand by Stephen King

This is my favorite Stephen King novel, and that's saying a lot, since I never leave the bookstore without some SK representation. The Stand is so long that if you get the uncut edition, you can step up onto it and get the bird's nests off your roof; even still, you feel depressed when you turn the last page. There's nothing like a story that begins with the end of most of humanity and then continues for about 1100 pages, peppered with the lyrically satisfying name Trashcan Man and lots of details about stomachs exploding. Life is gross. Books can be gross. You didn't want to finish those nachos anyway.

Tess Lynch is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Karina Wolf

Melmoth the Wanderer by Charles Maturin

These days, Melmoth the Wanderer is more an allusion than a perused text. Nabokov named Humbert Humbert’s automobile after the damned nomad; Oscar Wilde took "Melmoth" as a pseudonym, perhaps because of his shared status as eternal outsider. Maturin’s 1820 gothic novel begins with a bequest – a young Trinity student inherits his uncle’s estate and a manuscript, which relates the tale of his ancestor Melmoth, who extended his life by 150 years, presumably by selling his soul to the Devil. The only out from damnation is to find someone to take over the pact. The novel consists of a rococo series of nested vignettes, wherein characters encounter the cursed wanderer, sometimes peripherally. The pleasure (and challenge) of the text is in its stylish excesses.

Wuthering Heights by Emily Brontë

I re-visited Wuthering Heights when I taught at hokwan, a Korean cram school that aimed to stuff as many five dollar words possible into the minds of the foreign-born students. The odd task of reading Brontë’s novel aloud to a teenage boy (who loved it) made me appreciate its ingenious storytelling along with its elemental feelings. As a child, Brontë endured the deaths of two sisters and in response created Gondal, a detailed imaginary world that she sustained in letters and stories from adolescence to adulthood. Wuthering Heights retains a similarly corrective power; the novel is less a romance than a psychic outcry and self-assertion.

The Witches by Roald Dahl

The best children’s books are clever rejoinders to the early onset of life, primers for how to deal. Roald Dahl’s The Witches retains the violent menace of early fairy tales while offering readers a wry (and controversial) antidote to vanquishing the enemy, a kind of mass witch transformation and cat-led genocide. Dahl retains his spiky humor and incorrectness – also, his irresistibly charming prose. With lovely line drawings by Quentin Blake.

Karina Wolf is a writer living in New York. Her book The Insomniacs is forthcoming from Penguin. You can find her website here.

Elizabeth Gumport

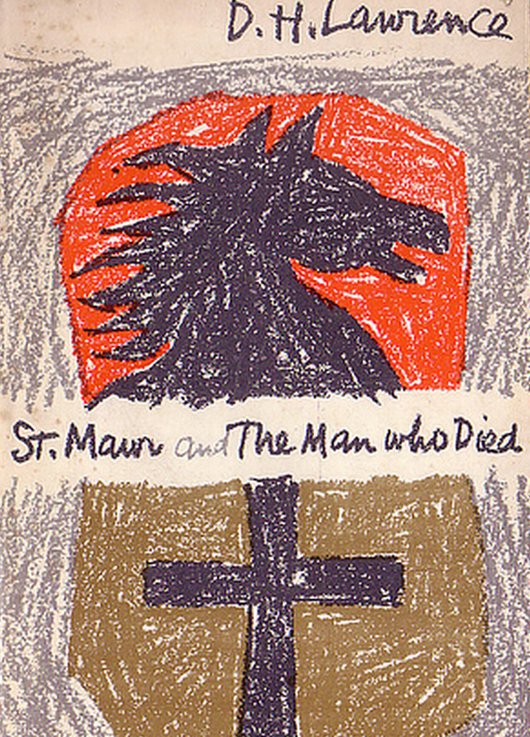

I am too adrift from myself to know what my favorite novels are. If I could tell you that, I could tell you so many things! But like rats fleeing a sinking ship, my former selves keep escaping me. One of the few things I am sure of these days is that I am twenty-five years old, and so like a child I go around insisting on my age. But we can forgive a child for identifying herself by how old she is, since what else would she have done with those months and years except live them? I, on the other hand, ought to have more and deeper moorings. Instead, the first page of D.H. Lawrence’s St. Mawr looks like a mirror: "Lou Witt had had her own way so long, that by the age of twenty-five she didn't know where she was. Having one's own way landed one completely at sea."

Reading St. Mawr, the feeling I had was not of identifying with the character but of being identified by them. I did not “find”myself. I was found, as if by a carrier pigeon bearing a note. A few months later, it was The Wings of the Dove that saw me: James writes that Kate Croy “had reached a great age for it quite seemed to her that at twenty-five it was late to reconsider, and her most general sense was a shade of regret that she hadn't known earlier. The world was different--whether for worse or for better – from her rudimentary readings, and it gave her the feeling of a wasted past. If she had only known sooner she might have arranged herself more to meet it.”

My sense of being “found”by these books was heightened by how I happened to read them: St. Mawr did in fact arrive for me by air, in a package from Amazon. It was a gift from a friend – the same friend who several months later would be the one to recommend The Wings of the Dove. A truly personal recommendation shows you something you don't often see, which is the way you hold yourself out to the world. That is what Lord Mark offers Milly Theale in The Wings of the Dove, when he shows her “the beautiful” Bronzino portrait “that’s so like” her. What matters is not merely what you are like, but that you are like something – that the world knows what you look like, even when you don’t. When shown the portrait, Milly admits she doesn’t see the resemblance.

Knowing that a book exists is one thing, being made to recognize its existence by someone else another. It is the fact of Lord Mark’s showing her the portrait, and not the portrait itself, that so topples Milly: “It was perhaps as a good a moment as she should have with any one, or have in any connexion whatever.”A personal recommendation is not the same as one cast out to anonymous strangers on the internet.

I will try, therefore, to be as specific as possible: if you are my age, self-absorbed, and aimless but not hopeless, you should read these books immediately. Perhaps the figure sketched in them will impress you as your own, and perhaps it will resolve something for you. Sometimes books enter your life at exactly the right moment. It doesn't happen as often as you'd think: like people, they tend to appear too early, when you are too foolish to appreciate them, or too late, when they have been claimed by someone else.

Elizabeth Gumport is a writer living in New York.

Isaac Scarborough

Tigana by Guy Gavriel Kay

Amongst all of the fantasy novels I devoured as an adolescent, Tigana is the only that holds up through the prism of passed years and moderate maturity – going back and rereading it remains the same mind-bending pleasure that it was when I was fifteen. Not only is it – a rarity in the subgenre – genuinely well written, but it does what fantastical writing is truly meant to: it comments on our world today, in a way that would otherwise be impossible. The power of names and naming stuck with me, and if there’s a reason why I today refuse to spell Ashkhabad “Ashgabat” Kay may very well have something to do with it.

Making Scenes by Adrienne Eisen

The basic willingness to describe modern life’s brutality – from lists of food consumed and bulimiacally purged, to the absurdity of what passes today for courtship – sets Eisen apart; her willingness to describe without going somewhere is also laudable. Reading Making Scenes is an experience closest to voyeuristically watching that cute neighbor across the hallway, except that she has begun to leave audiotapes on your doorstep of her – just as you suspected – far too aware and intelligent inner monologue. This voice sticks around.

Demons by Fyodor Dostoyevsky

By and large, Dostoyevsky doesn’t do plot: throughout his works, there are simply long periods of hysterics and contemplation, generally circling around a heinous crime committed in the very beginning of the work. Demons is no different in this respect, but here the hysterics come first, and then the crimes – a set-up that avoids the disappointment with which both Brothers Karamazov and Crime and Punishment end, and one that provides much more space for the author to develop his characters’ private insanities. And when it comes to madness, Dostoyevsky simply has no equivalent.

Isaac Scarborough is a writer living in Kazakhstan.

Sarah LaBrie

The Quick and the Dead by Joy Williams

A manifesto for young women destined to spend adulthood in a dimension just to the left of reality, the result of not having solidified quite correctly as children. The three teenaged orphans who guide us through Williams’ strange desert are peculiar but not precious, compelling in their very anti-Amelieness. It’s okay to be a genuine girl wacko, Williams tells us: if you’re smart enough to own it, you still get to win.

Autobiography of Red by Anne Carson

Fiction writers who start out as poets have an edge when it comes to building faultless sentences. Carson, a Classicist by trade, applies her skills as a translator of Greek verse to a novel about a monster named Geryon and his arrogant sometimes-boyfriend, Herakles. Building loosely on fragments of a poem by Stesichorus, Carson winds together scholarship and brutal wit to build a discomfitingly relatable love story.

The Counterlife by Philip Roth

In the autobiographical note that begins Notes of a Native Son, James Baldwin discusses coming to the conclusion that, before he could produce anything else of substance, he had to write about what it meant to be black. Through the lens of Nathan Zuckerman, Roth offers a metafictional take on the same question as it relates to Judaism while experimenting with perspective, structure, time and form. Probably the most skillfully written examination out there on the bond between fiction writing and the desire for control.

Sarah LaBrie is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Daniel D'Addario

England, England by Julian Barnes

In college, one of my mistakes was taking a class on comparative literature, after which I was left thinking that Britain or America could never produce a homegrown “national allegory.” Was I ever wrong! England’s image of itself is grist for this bizarre novel of ideas in which the nation is reassembled as a giant theme park for tourists—with a false king and queen and every famous Briton brought back to life. The novel questions the value of history and of myth—and despite its scorched-earth ending and brilliant dissection of the corporate profit motive, it does so with a bit of affection.

On Chesil Beach by Ian McEwan

Including Kazuo Ishiguro’s cloistered-England novel The Remains of the Day in my three favorites here felt a little unfair; it’s like being asked to choose among your children, when one is an ultra-sensitive genius. Instead I chose to include the instance in which Ian McEwan, predominantly a creator of tight narrative schemes, most closely approaches Ishiguro’s sensitivity to context (a past era’s very Britishness) and to character. For not the first but the most exhilarating time, McEwan’s games have real consequence: the fate of a young marriage.

Morvern Callar by Alan Warner

Novels with inert protagonists slay me, like Mary Gaitskill’s books, or Updike’s Rabbit series: watching things happen around characters is somehow more exciting and lifelike than watching characters conquer situations themselves (with the author’s help). The protagonist, the amoral Scottish girl Morvern, is glamorously inert; things happen around her as she observes and calculates. The scene in which Morvern, unmoved, lights a Silk Cut cigarette while staring at her boyfriend’s corpse is choked with an ennui Camus would envy.

Daniel D'Addario is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find his website here.

Elisabeth Donnelly

Another Bullshit Night in Suck City by Nick Flynn

Nick Flynn was a poet, and a good one, before he was a memoirist (shades of Denis Johnson), which is why his raw recounting of a fragile family stings with moments of sharp beauty and heartbreaking empathy. The plotline is relatively simple; when Flynn was 27 and working at the Pine Street Inn, a homeless shelter in Boston, he comes into contact with his long lost father. The book is elliptical and non-linear, echoing Flynn’s memory, diving into blood and family legacy, Flynn’s father’s delusions of grandeur and his mother’s suicide, homelessness, forgotten people, the way cities and vice can chew you up, and the burden of the past on Flynn’s own life. It will knock you on your ass.

Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison

The thing that sticks in my mind about Ralph Ellison’s masterpiece is that it’s so… weird. The imagery that he uses to describe the cruelty of this world is unforgettable: the nameless protagonist in his basement with 1,369 lightbulbs, the Black youths forced to fight for gold coins on an electrocuted rug, the riot (and spear) that rips through Harlem thanks to the Invisible Man’s gift of speech. While the book is ostensibly a record of growing up Black in a divided America, Ellison defies expectations at every turn, putting his character through scenes that are consistently strange and always feeling new (which left a legacy extending from John Cheever’s short stories to Paul Beatty’s The White Boy Shuffle); and this surprise means that Ellison can cut sharply with the anger, satire, and moody magnificence that’s fueling his work.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy

In the category of smart-girl-coming-of-age novels, Elaine Dundy’s American girl in Paris farce is particularly delicious. You’re in good hands with Dundy, after all, her biography was called Life Itself! (yes, with the exclamation point). The semi-autobiographical adventures of Sally Jay Gorce follow her as she dates, fucks, quips, and somehow makes a bad art film in the French countryside. It’s hilarious, and by the story’s end, proto-feminist Sally Jay is like a friend you don’t want to leave.

Elisabeth Donnelly is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here.

Lydia Brotherton

Brideshead Revisited by Evelyn Waugh

I was late to the Brideshead party – I only read it a couple years ago — but now I’m one of those people who owns the entire Granada miniseries and sort of goes on about gillyflowers and plover’s eggs too much. I can’t help it, and I’m not sure I can explain it without embarrassing myself: I really love this novel.

Orlando: A Biography by Virginia Woolf

When I first read Orlando, I was confused by its weirdness and delighted by its casually historical imaginings (there is absolutely no way to read fiction involving Elizabeth I that isn’t tacky except for this). And although I haven’t reread it in a while, I remember and misremember it like a tricky, particularly good dream. Maybe if there were an umami taste of novels, Orlando would be it.

Chéri by Colette

One of the reasons I like reading Colette novels is that in addition to being evocative of summer holidays in France I’ve never had, they have the potential to read as little lyrical self-help books. To be honest, what actually happens in Chéri is less important than the life lessons I manage to project onto all that description of pale, beribboned wrists and afternoon weather: how to wear silk robes during the day and take up with younger men, why it’s nice to upholster your furniture in dove-gray velvet, and — maybe most importantly—how to grow older, and, in your increasing age, more glamorous, demanding.

Lydia Brotherton is a soprano living in Basel, Switzerland. You can find her website here.

Brian DeLeeuw

House of Leaves by Mark Z. Danielewski

"Favorite novels" is a slippery idea. Favorite when? When I read it? Now, years later, in the memory of reading? I’m not sure I would even finish Danielewski’s novel today (this is saying something bad about me, not the novel), but its blending of pulpy horror and deconstructionist theory felt custom designed for where my head was at ten years ago, in the middle of college. I’ve never in my life been as consumed by the experience of reading a book. Probably I should try to read it again.

American Psycho by Bret Easton Ellis

One of the ways a satire can be judged successful is if a lot of people don’t understand that it’s satire. Another is if a lot of these same people get very exercised and moved to protest and write angry and self-righteous ad hominem reviews. American Psycho passes both tests. If there remain any doubters (after talking to some of my friends, I know they’re out there), the fact that Mary Harron directed the movie adaptation should be proof enough. This is the funniest book I’ve ever read, which makes it puzzling why much of Ellis’s other work is so unfunny and sometimes plain bad.

Veronica by Mary Gaitskill

Mary Gaitskill writes about complicated and uncomfortable emotional states with more precision and cold elegance than anybody else I have read. She’s most known for doing this in her short stories, and in some structural ways Veronica feels like a very long story rather than a novel. But those sort of classifications are irrelevant here. The book spares no one, least of all the reader. The prose itself is a representation of one of the novel’s central ideas: beauty is cruel, but no less beautiful because of it.

Brian DeLeeuw is a writer living in New York. He is the associate editor of Tin House and the author of the novel In This Way I Was Saved. You can find his website here.

Alice Gregory

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

Of all the boredom-fighting antibodies I have personally tested, The Secret History is the strongest; it obliterates even the most resilient strains of ennui within minutes. I've given it to boyfriends for long flights and family members on bad vacations. It's algorithmically entertaining, like if Dr. Luke wrote a novel. Some hashtags include: Bacchus frenzy, drugs, incest, cable knit sweaters, murder. It's a pretty solid bet for anyone seduced by dead languages or charismatic scholars. Also read Maura Mahoney's 1992 indictment of Donna Tartt. It's great; you can agree with Mahoney's distaste while still loving the book.

The Ambassadors by Henry James

The Ambassadors is a transitional novel; it's the preamble to "late James," which many consider to be incomprehensible and cartoonishly overwrought. But here you'll get a taste for his psychedelic syntax while still being able to read the story without diagramming its sentences. Our middle-aged narrator, Lambert Strether, over-thinks, under-acts, and witnesses the conversations of fin de siècle Paris like a stoned 15-year-old. Experiences seem to pulsate with alternating immensity and insignificance, giving way to "the terrible fluidity of self-revelation." He'll convince you that certain capitalized verbs and italicised pronouns have the power to unlock the universe.

Mating by Norman Rush

One of the prerequisites for reading Mating is indulgent friends. They might block you on gchat and mark your e-mail address temporarily as spam. You will never so thoroughly underline a book or force more quotations on loved ones. The unnamed anthropologist at the center of the novel is a flattering, if sometimes incorrect, model of female subjectivity. Her journey into an experimental Utopian community in Botswana — and her love affair with its leader — inspires rigorous introspection. Norman Rush will get you out of a reading rut, teach you more vocabulary than Eldridge Cleaver, and show you what it really means to intellectualize your emotions. Seriously! It's as good as Moby Dick and Anna Karenina.

Alice Gregory is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here and her twitter here.

Jason Zuzga

In Youth is Pleasure by Denton Welch

If Jean Genet, Temple Grandin, and M.F.K. Fisher were whipped into a exquisitely sensitive gay lad on the edge of puberty just before WWII and left to meander around the grounds and rills of an old hotel in a stifling British summer, where each new hair seen glistens with erotic potential, something like this novel might cut its way free from a chrysalis with tiny bejeweled silver scissors. The actual novel, along with its companions Maiden Voyage and A Voice Through a Cloud, were written by Denton Welch — after he was hit by a car while riding his bike and partially paralyzed at the age of twenty, before his untimely death at thirty-two. Never before or again shall peach melba be described in such a way.

Riddley Walker by Russell Hoban

Millennia after nuclear volley, humans emerge once more (alas?) into language and consciousness, improvising with shards of speech still eddying among the ruins. The novel is composed in that tattered language, a explosive experiment in textuality not as virtuoso authorial performance (though it is that too) but as constitutive of the arc of tale itself, the reader struggling into mindfulness as brutal Riddley adventures in attempts to think himself into some coherent sense of place and self and purpose. The last pages, an account of adults convened in audience for a trundled-along puppet show, crushed my heart in mournful hope.

The True Deceiver by Tove Jansson

Jansson is best known for her series of essential children's books about the Moominfamily of Moominvalley, characters that one may get a swift sense of via sampling the Polish stop-motion animations of the tales crafted in close collaboration with the author in the mid 1970s, as in these two excerpts: Sorry-oo and the Wolves or The Hobgoblin Arrives at the Party, etc. In The True Deceiver, a Tove Jansson novel for adults, a strange game of wits cracks through a long scandiinavian winter in a village by the sea between young Katri Kling — good with numbers but bereft of affect, called "witch" by the village children — and local children's book writer Anna Aemelin who fears raw meat and in the short summers paints photorealistic pictures of the forest floor populated with cartoon-like flower-covered rabbits. Over the course of the novel, a dog transforms, a boat is built, contracts with distant licensees of Amelin's characters are renegotiated for better terms, and the rabbits disappear.

Jason Zuzga is a poet and Ph.D. student living in Philadelphia. He is the non-fiction and other editor of FENCE. You can find his website here.

Helen Schumacher

Reservation Blues by Sherman Alexie

In Sherman Alexie’s debut, blues legend Robert Johnson has come to the Spokane Indian Reservation searching for the tribe’s advisor, Big Mom, in the hope that she can help him get his soul back from the Devil. Upon Johnson’s arrival, he’s given a lift by the reservation’s misfit storyteller Thomas Builds-the-Fire and, as a thank you, gives Builds-the-Fire his guitar, who then starts a band and subsequently gets a recording contract in New York City. It's nearly impossible to write fictionally about music and not sound corny, and often Alexie does. But it is a small fault compared to the grace with which he writes about the contemporary life and spirituality of Native Americans on the insular reservation.

The Heart Is a Lonely Hunter by Carson McCullers

When I first read Carson McCullers’ "tale of moral isolation in a small southern mill town in the 1930s," I was incredulous of a 23 year old writing something so brilliant and moving. But, looking back now on the novel 10 years later, it makes sense that someone that young would write about anger and idealism and passion with the confidence that she did. As we age, our idealism tends to become a shell of what it once was, and this book is one of our best reminders that it’s a tragedy to give up on our passion, no matter how bewildering it may be to express.

The Quick and the Dead by Joy Williams

A Pulitzer Prize finalist in 2000, Joy Williams’s The Quick and the Dead centers on a pivotal summer in the lives of three motherless teen girls living in the American Southwest: eco-terrorist Alice, increasingly catatonic Corvus, and beauty-obsessed Annabel. As the story expands, it is increasingly populated by an eccentric cast of characters who orbit around each other in a state of limbo as Williams uses her tricky prose to sort the living from the deceased. Her language reflects the character of the novel’s desert landscape, her hard-boiled words both merciless and stunning.

Helen Schumacher is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Andrew Zornoza

The Chrysalids by John Wyndham

"The armour was gone. She let me look beneath it. It was like a flower opening. . . ." The Chrysalids' odd future is a dinosaur: that depressing final hope that refuses to die out, ergo, the Millennium Falcon spinning and Obi-Wan Kenobi, singing: I'm a high-flying astronaut/crashing while/jacking off. . . .

Danny, the Champion of the World by Roald Dahl

Possibly, the truest, clearest, novel ever written and certainly the best guide to fatherhood.

The Green Child by Herbert Reade

An alternative accounting of the sublime, like a historical deconstruction of the obelisk in 2001: A Space Odyssey. Also, one of the worst opening pages in literature — Danielle Steele's Star (She was wearing a blue dress the same color as her eyes that her father had brought back from San Francisco) had more promise.

Crash by JG Ballard

"After having been constantly bombarded by road-safety propaganda, it was almost a relief to find myself in a real accident. . . .” The strange and compulsory reverse engineering of Crash and High-Rise to achieve Empire of the Sun follows an orbital trajectory not unlike one of Ballard's own tragic space pilots, tracing out one of the densest expressions of human feeling onto the tiniest constellation of obsessions.

A High Wind in Jamaica by Richard Hughes

An adventure story with cross-dressing pirates; a fevered dream; a study of human and meteorological caprice; and, abridged, The Story of the Vivian Girls, in What is known as the Realms of the Unreal, of the Glandeco-Angelinnian War Storm, Caused by the Child Slave Rebellion.

Andrew Zornoza is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is the author of the novel Where I Stay and the forthcoming Forest and Locket.

Morgan Clendaniel

Sometimes a Great Notion by Ken Kesey

Sleeper pick for the great American novel. It's about educated elite versus the working class,the taming of the west, self-determination, the merits and pitfalls collective bargaining, shattered dreams, natural disasters, infidelity, and the relationships between fathers and sons and husbands and wives. (Gatsby is about what? A super rich guy and a car accident?) More importantly, it's the book for ever plaid-wearing, faux-outdoorsmen type who went to a good school and couldn't actually chop down a tree with your decorative axe (that is me, and most everyone I know). Because it's partially about what happens when you're required to chop down that tree anyway, which is a moment of which I think many of us live in both horror and awesome anticipation.

The Odyssey by Homer

I guess this technically predates the idea of novels. But I've found that prose translations — try Butler — that treat The Odyssey more as story than trying to approximate a meter and feeling of verse are actually the best. In those cases, this reads just like a brilliant novel about a man's desperate attempts to get home to see his wife, with some monsters in the way. Most of the things that were vying for spots in my top three just contain plot devices that happened in The Odyssey first, so why not go right to the source?

Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien

I read all three of these books once a year. Every time, I find some new detail that I missed before, and it's amazing that Tolkien managed to pack these books so tight with details about the fully-formed worlds. I watched the movies recently, and they pale embarrassingly in comparison. It's a real lesson in the power of the written word and the human imagination: The movies are just flat approximations of something that is so tangible and vivid while you're reading.

Morgan Clendaniel is a writer living in Brooklyn. He is an editor at FastCompany.com. He twitters here.

Jane Hu

The House in Paris by Elizabeth Bowen

The pitch of this novel is perfect. Two orphaned children, Henrietta and Leopold, meet for one day in a house in Paris while on separate journeys to new homes. The novel is divided, like Woolf’s To the Lighthouse, into three parts — the middle section takes place in “The Past.” Here, we discover the world of romance and intrigue that produced Leopold and subsequently abandoned him.

The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton

Newland Archer and Ellen Olenska’s forbidden affair is one you wished you could had, because their experience of unfulfilled love actually looks richer than any resolved or established relationship. If you’re not crying by the final pages, check and make sure you’re reading the right book.

The Sound and the Fury by William Faulkner

The bleakness of Faulkner's novels is part of their hopeless beauty, and I will take the desperation of Caddy Compson and Quentin Jr. over Lena Grove’s more hopeful journey always. Introduced through Benjy’s eyes, Caddy is the pure image of love. In fact, every line trembles with love, or poetry. You might not always know what happens in terms of narrative, but you will feel why.

Jane Hu is a writer living in Montreal. You can find her website here.

Ben Yaster

The Tin Drum by Gunter Grass

The Tin Drum's a memorable read for its absurdity — or magic, depending on your attitude toward the diminutive by choice. But what I remember most clearly about this novel wasn't the narrative of stunted Oskar Matzerath's misadventures in Poland and Germany before and after World War II. It's the vivid, surreal details — the eels slithering in and out of the horse's head on the sea shore, the woolly carpet Oskar lays down in the hall of his boarding house, the German pillboxes assembled as if the Axis defense line were a sculpture garden — that have stayed with me. That, and Alfred Matzerath's death upon swallowing his Nazi pin. Just desserts, I suppose.

The Moviegoer by Walker Percy

There have been times in my adulthood when the idle waywardness described in The Moviegoer has struck too close. If you're a regular reader of This Recording you've probably felt the same thing. But unlike Binx Bolling, I don't go to the movies because I'm cheap. (I could have practically bought a share of News Corp. for what I paid to see 20th Century Fox's Avatar 3D. This is actually true.) Nor do I lament the passing of the southern gentleman's life of leisure, the birthright stolen from Bolling. When I read this book, I didn't understand it as an expression of existential angst so much as a comeuppance for the patrician set during the rise of middle-class postwar New Orleans. Then again, my mom has given me an unsolicited Nation subscription every year as a birthday present. (This is also actually true.) Whatever your take, this novel is a moving illustration of the sadness of not knowing what you want in life. Folks who recently graduated with humanities degrees can surely sympathize.

Lush Life by Richard Price

Let me cut you off before you begin: Clockers is the better book. I won't argue otherwise. Lush Life resonated more strongly with me, however, because it described something of which I was a part: gentrifying New York. The novel's ostensibly a crime procedural. But the story unspooled is more than a whodunnit. It's a keen examination of urban life and its contradictions, of the permanency of place and the flux of people inhabiting it, of how timeless themes of love and death emerge from the day's pettiest trifles. Don't let me get too lofty, though. It's also a fun, entertaining read, full of wry dialogue and carefully drawn characters. And I've heard that the restaurant was based on Schiller's Liquor Bar. Sounds about right to me.

Ben Yaster is a lawyer and occasional writer. He splits his time between New Haven and Brooklyn.

from a cover for 'The Sea, The Sea'Barbara Galletly

from a cover for 'The Sea, The Sea'Barbara Galletly

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

While most concur about Flaubert’s specialness, generally, and this is the most popular of his books, I imagine many would disagree with me about this choice for best book (Flaubert’s Sentimental Education was more careful still, and more male, and often comes up first for smarter people). But this is, for me, the best book and most familiar. A novel on novels, it is beautifully written, and laden with subtle and less subtle subtext: each word is the mot juste, in as many ways as possible. Each sentence appears almost living, richly embedded with precious aesthetic gifts to you, the reader; but it is also poison, and driving you mad. “She was not happy and had never been,” Emma reflects after another furtive, too-hasty encounter with Leon. “Why was life so inadequate, why did the things she depended on turn immediately to dust?”

The Sea, The Sea by Iris Murdoch

This novel is no longer my favorite, but it certainly was at one point in college when I was better read. Like all of Iris Murdoch's books, it really pushed me, especially away from it. She is so brilliant and so compelling a writer though that the novel's sum total is worth the angst it will cause to see it through. Amongst other things, Arrowby will teach you something about how to write, and that the contents of memoirs matter very much.

The Ice Palace by Tarjei Vesaas

When I’m trying not to sound like an idiot for choosing the greatest novel ever to be the “best” I call The Ice Palace my favorite novel. Written by Norwegian writer Tarjei Vesaas, it is the story of two young girls who become friends. But it is really a masterfully written story about the complexity of emotions and pain generated during, perhaps as a byproduct of the birth of a relationship between two young girls who are just on the verge of understanding who they will be and where they have come from. And it contains the most stunning description of ice and death I have ever read.

Austerlitz by W.G. Sebald

It is my opinion that W.G. Sebald is the greatest prose writer of the second half of the 20th century. His careful empathy for his difficult subjects is matched by his great ability to adapt modern media and traditional form to fit his stories. In the way that a great poem is neither billable as fiction nor nonfiction, Sebald's complex works transcend the category of novel (or non-fiction). The Emigrants and On the Natural History of Disaster are also great books, but Austerlitz, his last one, he comes closest to the sublime.

Barbara Galletly is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Elena Schilder

Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy

I read this once at 16 and once at 25. I remember reading the opening as a teenager and thinking that I'd identified some kind of writerly trick — an expansion of human thought and experience so exaggerated as to be comical. The second time I read it everything made me cry.

Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell

This book created whatever mythic landscape has since existed in my mind labelled "the novel." I'm not sure whether to be grateful for that or not. It is full of bad writing and bad values which probably misshaped my pre-adolescent brain. But I love it; it's what I think they call "juicy."

Home by Marilynne Robinson

I reread this one recently and remembered that it is a really painful book — as in, a book full of pain. The emotional dynamic among the characters stays at an unrealistically high pitch throughout. This is a book about what it would feel like if we were always thinking of other people.

Elena Schilder is a writer living in New York. You can find her website here.

Almie Rose

Lunar Park by Bret Easton Ellis

American Psycho and Less Than Zero are too obvious, though I love them also. But there is something about this one that I couldn't shake after reading it. This might be his best. It's a fake autobiography of his fake life. It made me laugh out loud: "Without drugs I became convinced that a bookstore owner in Baltimore was in fact a mountain lion." Then suddenly it turns into a horror novel and it's creepy as hell. There's one scene in particular, towards the end, with this thing...I don't want to describe it.

From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by E.L. Konigsburg

The best novel about New York ever written. Every time I read it I practically devour it with excitement as it twists and turns into its clever ending. Yes, I know it's technically a childrens' book. I don't care. Raise your hand if you read this and didn't want to hide out in the Metropolitan Museum of Art and bathe in a fountain. If you didn't raise your hand you are missing your soul.

The Land of Laughs by Jonathan Carroll

This book is just bizarre which is probably why I like it so much. It also has the best character name ever: Saxony Gardner. This is the novel I keep coming back to. It's like a mix of David Lynch and Roald Dahl. The main character refers to his father's Oscar winning film as Cancer House. The book is darkly funny and made me want to read every scrap Carroll's ever written. His imagination is so good it makes me angry.

Almie Rose is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Alexis Okeowo

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle

This book is technically a children’s novel, but I usually believe that children’s books are the most appealing and universal. It’s a story about time travel – one of my all-time favorite subjects! – and finding your moral strength and trusting your abilities. What struck me about A Wrinkle in Time, even as a kid reading it for the first time in my backyard in Alabama, was how intelligent and layered the writing and plot were, and how enthralling this galaxy was that L'Engle created. I couldn’t stop dreaming about falling into her worlds.

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Adichie

This book was the only time I’ve read a novel that reminded me of my life experiences so much it was kind of excruciating at some points. The pain aside, Half of a Yellow Sun is the best example of grand, lyrical storytelling I've ever seen. The novel is set during the Nigerian civil war, and is a story both about struggling to live with compassion and dignity during chaos, and about a love affair that consumes a British journalist and two Nigerian sisters.

What is the What by Dave Eggers

I think I swooned at the first point in the novel when Eggers started writing from the perspective of the South Sudanese protagonist: the diction and the tone were perfect and reminiscent of the regal, funny Sudanese people I knew in Africa. The story about the Lost Boys (and girls) of Sudan is incredibly sad, yes, but the writing is so beautiful and the voice of Valentino Achak Deng so important, that I didn’t mind. What is the What ravaged my emotions, but in a good way.

Alexis Okeowo is a writer living in New York. She is an editorial assistant at The New Yorker. You can find her website here.

Benjamin Hale

These aren’t necessarily the books I would take with me if I were banished to a desert island; there’s no point, I know them too well. These are three of the books that have most profoundly changed me, changed my understanding of literature, and changed the way I want to write.

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass

Kurt Cobain, with characteristic self-loathing, once described "Smells Like Teen Spirit" as “basically a Pixies rip-off.” If there’s a book to which I would happily acknowledge a personal debt with such groveling humility, it would be this one. My own novel is basically a rip-off of The Tin Drum. The Tin Drum is among the bravest books ever written.

The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow

Henderson the Rain King is a better book, and I thought of listing it instead, but I chose Augie March because it was the first Bellow book I read, and the one I set out to study, in the way an apprentice chef might try to reverse-engineer a mystery sauce by taking sips and altering ingredients accordingly, trying to discover how the master made it. I lent my copy to a friend recently, who told me I’d apparently circled a certain paragraph and wrote in the margin, "LEARN HOW TO WRITE LIKE THIS."

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Arguably the first novel and, I would argue, the best. To me, the Man of la Mancha represents the spirit of the novel: comedy in the front, tragedy in the back. It is a story that begins, but never ends.

Benjamin Hale is a writer living in New York. He is the author of The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore.

cover by joshua k. marshallRobert Rutherford

cover by joshua k. marshallRobert Rutherford

Let me first assume a male audience. The books that you read in your angry youth tend to remain after the emotion they engender fades. Though the blueprint lightens, you realize the man you thought you'd become are also the men the authors wanted to be, but weren't. The three imaginary men I thought I'd become but lacked the conviction are:

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway wrote his first novel "not to be limited by the literary theories of others, but to write in his own way, and possibly, to fail." At least when he was young, he lived a life more full. It's easy to romanticize Ernest driving an ambulance in World War I and defining the lost generation in Paris, but it's easy because he actually did those things. No one should be allowed to write anything until they are seriously wounded in a war at least once. Hemingway shot himself in the head with a double barreled 12-gauge shotgun at his home in Ketchum, ID.

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller

Fifty years before you were born, Miller put to words everything you have ever wanted to do in your life but you can't because you are too weak, afraid and lazy. He fucked his pen across Paris, and then raped New York in Tropic of Capricorn. Jack Kerouac was an aimless hobo in comparison. Miller died in the Pacific Palisades and his ashes were scattered off Big Sur.

The Rum Diary by Hunter S. Thompson

A novel by an alcoholic before he became a drug addict is the best reason for sticking to alcohol. There's very little in this book of the Hunter caricature that came later, so it feels like a the work of a different author, the caterpillar before the cocoon. It's laconic instead of hyper and helps you realize that before he was a gonzo journalist he was just a kid who idolized Jack Kerouac. Thompson shot himself in the head with semi-automatic Smith & Wesson 645 at his home in Aspen, CO.

You wake up one day and you're happy, and you don't want to kill yourself. And that's depressing because it means you can't be a writer. To the men we became, and the authors who showed us how not to become them.

Robert Rutherford is a writer living in Los Angeles.

Kara VanderBijl

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

This book, which I believe I have read at the turn of each season since I first discovered it, inspires in me a strange mixture of nausea and awe. Flaubert's mastery of the French language remains the standard by which I measure my own understanding of it; his sad lady protagonist remains my greatest fear and a faultless mirror. Emma, c'est moi.

The Go-Between by L.P Hartley

One must disregard the fact that Hartley's opening line is now as over-quoted as a Frost poem in order to appreciate its truth. I treasure this story as a sort of secret garden, uncomfortably recalling the innocently ignorant period of my childhood. Plus, since this novel is ridiculously under-read, I have the pleasure of relating its poetry to anybody within earshot.

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

Eco wooed me by quoting Latin and refusing to translate it on virtually every page. In other words, this medieval murder mystery occupies the Read This And Understand Your Humanity shelf, a black hole of disproportionate presumption. A category of people, to which I belong, will read it and take pride in the fact that they grasp very little of the universe. It was not written for them.

Kara VanderBijl is a writer living in Chicago. You can find her website here.

Damian Weber

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich

After reading too much, and writing three of your own unfinished novels, you can't read fiction anymore. Sure you can mine for ideas, but mainly your bullshit meter won't let you finish 20 pages. That's why we only read non-fiction now. Or Louise Erdrich. She never sets off my bullshit detector. On a different topic, we need to write more short stories.

Hyperion by Dan Simmons

After you're done reading all the best literature in the world, you get over it, and move on to genre fiction. Especially if you want to write yourself, and you're sick of being limited by your own boring imagination. Did you know you were as imaginative as Dan Simmons? Did you know you could break free and write the craziest awesome shit?

Trout Fishing in America by Richard Brautigan

If all my favorite music lyrics could be assembled in a narrative of my life with the girl I like and our daughter, I would read it over and over like I do Trout Fishing In America.

Damian Weber is a writer and musician living in New York.

Jessica Ferri

The Loser by Thomas Bernhard

Do you hate everything but have a great sense of humor about it? Read Thomas Bernhard for all your obsessive, misanthropic, neurotic, suicide-inducing rants. Because really, when all you want to do is play piano but Glenn Gould studies at your music conservatory, what the fuck is the point of living except to complain about it?

Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger

Over a lunch of Frog Legs and an uneaten chicken sandwich, Franny realizes that she's surrounded by "section men," and needs to ceaselessly pray. Zooey, her actor brother, after a long marinade in the tub, calls her from the living room to tell her about Jesus and the Fat Lady. You will read this dialogue and you will laugh. This will be followed by a tightening in the chest.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Jane Eyre is the book in your middle school "media center," that calls to you with the intense-looking girl on its cover and the author's familiar sounding last name. You might want to make it a re-read past the age of nine, however, because Jane Eyre is one of the greatest novels ever written, and you'll need to have loved and lost and been "poor, obscure, plain and little," to fully understand how awesome it is for Jane to bust up out of a terrible situation in 1847 and go traipsing through the English rain, risking pneumonia and God knows what else to become the best narrator any reader could ask for.

Jessica Ferri is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Britt Julious

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

My body shakes thinking of the characters in The Secret History. I don't think I've despised characters so succinctly and passionately. The longer I think about the plot and the characters' decisions, the more incensed I become. But never have I had such immense, perhaps even overwhelming pleasure reading a book. Characters that challenge me this much only remind me why I love reading.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy

The Dud Avocado is a whip-smart little gem of a book, one that I've read three times in the few months since I've finished it. Sally Jay is young and silly and tricky. I relate to her almost selfishly: I hate knowing that other people will read thus book and see themselves (flighty, sarcastic, anxious) reflected from line to line. I'd like to believe that Sally Jay and I are kindred spirits, and that everyone else is just pretending to know what it's like to be us.

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes' writing is lush. Its lushness makes me wince, for I can only dream to write as uniquely and profoundly as she did. There are certain passages I've underlined and like to revisit from time to time. My masochistic nature breaks free; reading her work is torture for the young writer who only wishes to capture a portion of that indescribable quality each page possesses.

Britt Julious is a writer living in Chicago. You can find her website here and her twitter here.

Letizia Rossi

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Sometimes you just want to get the fuck out of New York. Get away from the bullshit, the social climbers, the sycophants and just head back to your home town. You're tired of getting wasted, open bars, not even knowing whose party it is; the antics of bankers, bohemians, socialites; conversations about ‘content’, banal proclamations, networking, feigning interest, working hard to get ahead. These assholes are all just spending their Daddy's money anyhow. I mean does anyone even really love anyone or is it just what they represent?

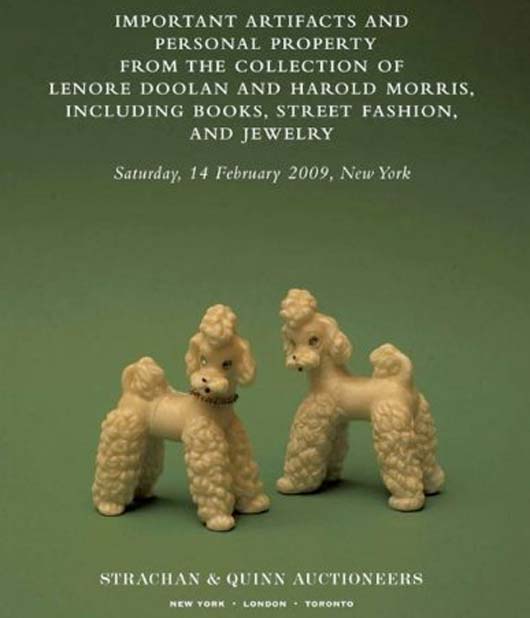

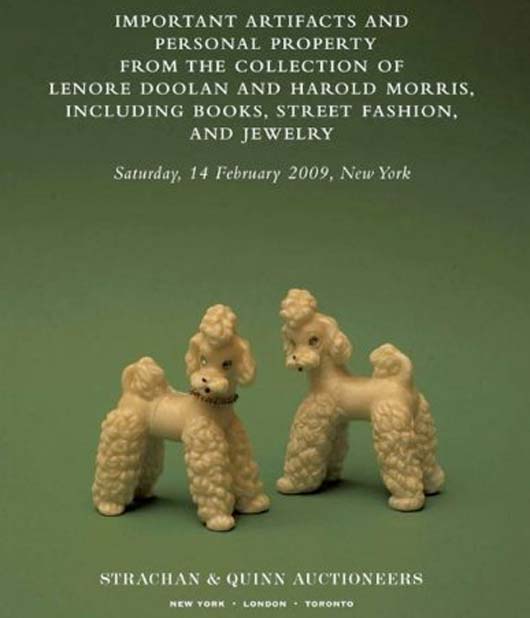

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry

by Leanne Shapton

My ex-boyfriend had the best stuff, amazing stuff, the stuff of dreams: LPs, 70s era McIntosh receivers, silk velvet chaise lounge, arts and crafts desks, criterion dvds, vintage file cabinets, Godard posters, fiestaware, le crueset, butter bell, sheets that – somehow tastefully – match the towels, William Eggleston books, walnut bookshelves filled with every book you’ve meant to read (arranged by color), a ship in a bottle, vintage Fernet Branca ad /(souvenir from trip to Buenos Aires). Does anyone really love anyone or is it just what they represent?

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13¾ by Sue Townsend

Accept no imitators! This is the genre-defining self-deprecating epistolary diary novel. (Not mad at you Bridget Jones and Nick Twisp.) SPOILER ALERT: "Love is the only thing that keeps me sane..."

Letizia Rossi is a writer living in Williamsburg. You can find her website here.

Will Hubbard

Justine by Lawrence Durrell

I am drawn to books that present an unthinkable world. A world that it would be impossible for me to inhabit because of my limitations. A world in which my head would explode. Such is the mercy of a great novel – that it only partially explodes our heads, privately and pleasurably. The Alexandria of Justine is a place where the colors of the sky and water are not colors you've ever seen before. And the politics of the place – both municipal and sexual – are impossible to understand and thus easy to enjoy. Every character constitutes a nation unto him or herself – there are cryptic alliances and yes, a great deal of sex, but eventually everyone stands (or dies) alone. Nobody prevails. Alexandria prevails. Durrell felt that he needed to write three sequels to explain away all the misery and intrigue of Justine – I would have preferred that he didn't. In fact, I've never read Justine all the way through – and still, somehow, it's my favorite book. Explain that.

The Colossus of Maroussi by Henry Miller

Everything I said above, subtracting the abundance of sex and adding long, rich passages about the qualities of the light at various Greek archaeological sites. I know that strictly speaking this is not a novel, but when a human being has the experiences Henry Miller did and can process them with the grace that he does in this book – there's nothing to really delineate it from fiction. If a novel is a long story that didn't happen, then Colossus for all intents and purposes is a novel – it simply could not have happened. Again, our limitations. The most sensitive of us is far too dull.

A Fan's Notes by Frederick Exley

The narrator of this novel loves football, specifically Hall-of-Fame Giants running back Frank Gifford. It's an easy enough world for some of us to imagine – long Sundays in dark, cool, damp places checking alternately the score on the television and the amount of beer in our glass. But sport only frames Exley's story of human weariness and wariness which, again, gives me supreme pleasure because I cannot imagine surviving the mental circumstances of its narrator. That the protagonist shares his name with the author we forgive because the book draws heavily – some say absolutely – from the real Frederick Exley's life, which at times was more horrific than anything in his 'fictional memoir.' Punctuated liberally by the arrival of white-clad men from mental institutions, A Fan's Notes manages a steady undercurrent of hope; I doubt its author ever could.

Will Hubbard is a writer living in Williamsburg. His first book of poetry, Cursivism, is forthcoming from Ugly Duckling Presse in April.

Durga Chew-Bose

Adolphe by Benjamin Constant

“Nearly always, as to live at peace with ourselves, we disguise our own impotence and weakness as calculation and policy; it is our way of placating that half of our being which is in a sense a spectator of the other.” Forgoing traditional imagery, Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe is furnished instead with emotions, “sleepless nights,” and mood. Sober stuff, yes, but a fortune of maxims, I promise! Rumored to be based on Constant’s liaison with Madame de Staël, the plot is classic: a doleful and somewhat reclusive young man, seduces a Count’s lover. Their affections grow alongside the young man’s doubts and eventually, desire’s cruel law of diminishing returns overcomes. While short — less than a hundred and fifty pages — I suspect Adolphe has become my skeleton key; that which can unlock, or at the very least let breathe (read: indulge in!) some of my most pressing reservations. For anyone who is preoccupied with feelings, especially love, this novel is a trove of its articulations, both physical and mental.

The Lover by Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras’s The Lover is best read over the course of one day. It possesses you. And like on especially hot summer afternoons where the sun's heat appears to be coming from inside you, Duras’s prose spawn that similarly sublime and somewhat punch drunk sensation from having sat outside for too long. My copy of it is worn, underlined, scribbled on, and yet, it still smells new. I refer to it not only for the story of the unnamed pubescent protagonist and her lover, but for the descriptions of women, like Hélène Lagonelle, who are "lit up and illuminated," (unlike the men who are "miserly and internalized.") That addled mix of envy and adulation—of knowing the nude shape of your friend’s body even when she is clothed, the convex, the concave, of using words like 'roundness,' 'splendor,' and 'illusionary' and then following them with words like, 'never last,' and 'kill her' — confirm the novel’s overture, a sentence that I copied over and over in my notebook what feels like years ago, unaware of its enduring potency: “Sometimes I realize that if writing isn't, all things, all contraries confounded, a quest for vanity and void, it's nothing."

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

I care deeply about this book because it pools together so many thoughts that for so long I assumed were separate. It reads like trinkets in constant orbit, like "that enchanted calm which they say lurks at the heart of every commotion." It's also terribly funny, diagnostic, and warm; the finest combination! One of my favorite chapters, 'The Tail,' begins with this: "Other poets have warbled the praises of the soft eye of the antelope, and the lovely plumage of the bird that never alights; less celestial, I celebrate the tail." I simply cannot get enough.

Durga Chew-Bose is the senior editor of This Recording. She tumbls here and twitters here.

Rachel Syme

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

I am not ashamed to say that I loved the film adaptation of The Hours — if only for that twitchy Philip Glass score and to see Meryl Streep wring her hands and cry on a kitchen floor covered in egg yolks (I prefer this flustered Streep to the daffy Nancy Meyers version who makes croissants stoned) — but I do understand the bit of damage that the film and the book that spawned it did to the venerable cultural status of Mrs. Dalloway. Not that the The Hours didn't do Woolf justice; it's just that one could get the impression that it's not entirely necessary to go back and read the source material. The essence is there in the film, it's infusing the whole thing. Which is all fine! But if you have a deeper interest in writing, or women, or parties, or human frailty, or moral quandaries, or in passions v. the banal scutwork of daily life, then I would prescribe the original to you like a tonic. Reading Clarissa's inner monologue, her incantations about all of the things she can never have, that life will never be for her; this is how I learned that writing born from empathy just feels different, and those that master it are sorcerers.

Anagrams by Lorrie Moore

A small but important truth to get out of the way first: As a novel, Anagrams is kind of a disaster. Other novels likely talked some shit about it in the hallways, wondering why it had to come to class so grubby and loose and patched together. The book is — if we want to get technical about it — closer to a novella that has been smashed together with a few short stories and sealed with word pectin. Each little fragment features characters with the same names (Gerard and Benna) and a few overlapping characteristics that carry over between story breaks, but the flow is not immediately scrutable or consistent; it lumps along. And I couldn't love it more. As is the case with most things that get slammed into lockers at first, Anagram is a slow burner, this late bloomer of a book that takes some time and investment to blossom on you. It is a White Swan willing to twirl overtime with an Odile inside. I get more out of re-reading this book than I do most any other, if only because I think it's the funniest and harshest and loneliest Moore has ever been on the page, and her talent for owning that particular literary trifecta is well-documented. In an interview with The Believer, Moore said that she wrote Anagrams "longhand on a typewriter, and it probably contained more crazy solitude than any other book I've written." And she's right! It's a crazy lonesome read. But also, there are these glittering moments of warmth that peek through, sharp enough to break the skin: Life is sad; here is someone.

The Debut by Anita Brookner

"Books about books" is a genre that is usually best avoided (unless you find great pleasure in watching someone try to high-five himself), but Brookner's story about Ruth Weiss, a 40-year-old Balzac scholar who, in the first line, discovers that "her life had been ruined by literature" is rich and savory, and magically absent of cliche. The book moves ever so slowly, as Ruth reflects on lessons from her youth ("moral fortitude…was quite irrelevant in the conduct of one’s life: it was better, or in any event, easier, to be engaging. And attractive.”), on her selfish childhood and one terribly broken love affair, and on how she came to be an academic loner writing a neverending study of Women in Balzac's Novels. Ruth's story has an Olive Kittredge sheen to it, in that not much happens outside of a lonely woman's meanderings through her own life, and yet it has a British crackle to it, and a tender pacing that could only belong to a mature writer. Brookner published The Debut — her debut — when she was 53 years old, and you can immediately tell that the prose comes from the mind of someone who has done some living and losing and mellowing and accepting, and is on that phase of the roller coaster where your jaw is settling back in. I read this when I want to feel like I am consulting an swami of calm; oracular spectacular, a soothing voice that also tells you how to live.

Rachel Syme is the books editor of NPR.org. She tumbls here and twitters here.

Amanda McCleod

The Brothers Karamazov by Fydor Dostoyevsky

Poor Fydor! Poor Dmitri! Poor Ivan! Though their fates may have been brutal it is Alexey Karamazov I feel the sorriest for! Fated to be Dostoyevsky's great protagonist in a second novel which he failed to complete within his lifetime. Alexey Karamazov is my favorite character of all time, easily. He appears to be modeled after saints and folk heroes alike, and is possessed with a bottomless kindness that is shocking in contrast to his own father's maniacal meddling. What I would give for that second book to have been completed! I had the great pleasure of reading The Brothers Karamazov along with a few friends in recent years and together we fostered the notion that everyone is at heart one of the three brothers: The realist Ivan, the impassioned Dmitri, or the gentle Alyosha. We hope no one we encounter is a Smerdyakov or Fydor, and we've all met our fair share of Grushenkas. I've loved an Ivan and befriended many Dmitris, but I'll always be an Alyosha.

Stranger In A Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein

Heinlein captivated the world so thoroughly with Michael Valentine-Smith, the man from Mars, and his concept of Grokking that "Grok" has been incorporated into the English language. From the novel itself: "Grok means to understand so thoroughly that the observer becomes a part of the observed." Since first reading Stranger I've held this notion in the back of my mind whether encountering art or others. I can honestly say that I never expected I would encounter such a earnest concept in a work of science fiction, yet Heinlein achieves many such beautiful instances as this one continually throughout the novel. At times this read can be campy, but that really only adds to the pleasure of examining humanity through the eyes of a man reared in martian culture.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche

For one thing I can't think of a week since I've read this book that the Eternal Return hasn't crossed my mind. It is a horrifying thought, that is unless you live with such conviction that you reach Amor Fati. If you were doomed to repeat all of your days eternally, could you stomach living them? This is the sort of thing I'd like to wake up and worry about every morning, though often I am most worried about where caffeine will come from and how soon it will come. Thus Spoke Zarathustra was extremely enjoyable for me to read, but this is surely because it mimics the New Testament in style. As a product of catholic school it was actually very comforting to be reintroduced to this sort of language when I first read this novel. This quickly became extremely amusing, as Nietzsche's eccentric Zarathustra verges on zealotism often and backhanded critiques against religion are delivered feverishly. If you haven't delved into Nietzsche before I'd say this is a fun place to start.

Amanda McCleod is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Yvonne Georgina Puig

All My Friends Are Going To Be Strangers by Larry McMurtry

Larry McMurtry is pretty much my hero. He's one of the most productive and least pretentious writers around. This is a beautiful, hilarious story written in clear, simple McMurtry style, and much of it is set in Houston, Texas, my hometown. Not many novels are set in Houston because generally speaking it's an uninspiring place. But this book, along with Terms of Endearment, make me nostalgic for oppressive humidity and flat urban sprawl and larger-than-life hairdos. I don't enjoy writing book reviews (unless I love the book I'm writing about), or analyzing books to pieces. I just enjoying reading, and then enjoy loving the books that I love, if that makes any sense. McMurtry is easy to love in this way because he tells such great tales. Three summers ago, I started it on a hot day in Austin, Texas, a few miles from where the book opens.

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

I love books populated by characters from Sarah Palin's "real America." Their problems are less self-indulgent and more insidious. "Real" Americans, in my opinion, are much more interesting than people from, say, Santa Monica. A Thousand Acres, an incredibly poignant and masterful first-person re-imagining of King Lear, set on a farm in the Heartland, is really a story about a family confronting evil. Yet everywhere you turn someone is baking blueberry muffins, or fixing coffee for the pastor, or making a casserole for the church social. Smiley gives you a slow drip of Godly politesse, and then suddenly you're drowning in utter devastation. I think this is how darkness really functions.

Lady Chatterley's Lover by D.H. Lawrence

A friend who recently graduated from Columbia told me she took a class there on D.H. Lawrence which was full of Lawrence detractors, and apparently there's this whole faction of them out there in the world, who go around disputing Lawrence's reputation as one of the greats. Maybe this is a known thing, but not to me, and I'd like to tell those people to shove it. It's enough that Lawrence wasn't treated very kindly while he was alive. These haters would be lucky to describe a flower just once as beautifully as Lawrence described flowers all his life. We need more writers in love with flowers, who find faith in nature, and who remonstrate the vulgarities of the world. Thank goodness for Lawrence's sensitive, deep-seeing soul. I love all his books, but I think Chatterley is his strongest narrative, and a good place to start in reading his work.

Yvonne Georgina Puig is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

If You're Not Reading You Should Be Writing And Vice Versa, Here Is How

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)

CITIES

CITIES  Tuesday, January 3, 2012 at 10:52AM

Tuesday, January 3, 2012 at 10:52AM