This Blessed Arrangement

by KARA VANDERBIJL

The Marriage Plot

by Jeffrey Eugenides

406 pages

Madeleine Hanna's time at Brown University has been confusing: she chose to study literature out of (she feels) a superficial love for the works of Austen, James, and the Bronte sisters, but all the cool kids on campus are smoking pot and spouting unintelligible streams of Derrida. She debates the pros and cons of a primarily black wardrobe, and wonders whether or not she should wear her glasses. Now, on a sunny graduation day in 1982, she wakes up with a massive hangover and the sneaking suspicion that her life is not going quite as planned.

It should come as no surprise to readers that Jeffrey Eugenides, who has turned out a novel every decade since his own graduation from Brown in 1983, should return to youth in his latest, The Marriage Plot. He is perhaps our last Greek tragedian; his pet device, the coming-of-age novel. Yet Eugenides does not simply have us sit back on our heels as he unravels the average young American’s psyche — he has flavored the absurdly normal with the equally strange. The Virgin Suicides adopted a grubby, husky, continually horny collection of boys to witness the demise of five young suburban sisters, in the style of a Greek chorus. In Middlesex, his second, Pulitzer-prize winning bildungsroman, Eugenides transforms what would have otherwise been a boring immigrant tale into a fantasy involving incest and the intersexed.

Fewer fireworks fizzle off the pages of this year’s book, however — the solemn opening, "To start with, look at all the books" rings neither of suicidal gore nor of Middlesex’s daring, "I was born twice, first as a baby girl on a remarkably smogless Detroit day in January of 1960; and then again, as a teenage boy, in an emergency room near Petoskey, Michigan, in August of 1974." The exhortation is tamer, perhaps a bit more nostalgic, with something inherently self-congratulating built in. Look at all the books. Eugenides, himself an instructor at Princeton, winks at his audience with a tale that is as in tune with our super-critical generation as it is pleasing to our innermost souls. To say that a coming-of-age novel is pleasing to the populace, especially in age when art has become purely self-reflective, is an understatement.The Marriage Plot, like all novels of its kind, tickles that sensitive place you were in while you were growing into yourself; the pleasure found in identifying with a young, struggling protagonist is practically masturbatory.

Of course, when Eugenides instructs us to look at the books, he is really instructing us to observe his Madeleine: bright, beautiful, Waspish despite herself, and altogether unremarkable except for the fact that her senior thesis deals with the 19th-century "marriage plot" — that literary trope exploiting women’s societal need to marry in order to create riveting romances, a trope which ultimately disappeared with the sexual revolution. But “sexual equality,” argues Eugenides through his heroine, "good for women, had been bad for the novel." Novels had lost their primary conflict — resolution, once complete in matrimony, had to find other ways to express itself. Ironically, while Madeleine argues her little heart out on paper, she finds herself caught in an impossibly Victorian love triangle. Daydreaming, spiritual — and Hanna parent-approved — Mitchell Grammaticus has long held a torch for her, but Madeleine has fallen in love with a brooding, handsome biology major named Leonard Bankhead whom she met, of all places, in a literary criticism class.

Leonard has a big secret, though: he is manic-depressive, a reality that lurks underneath his charisma and wide-ranging intelligence. Even though he’s bedded half of Brown, he is magnetically attracted to Madeleine, a girl who has the audacity to believe in romance even when “the French theory she was reading deconstructed the very notion of love”. After a whirlwind affair that begins with an innocent slice of apple pie and ends between Leonard’s ratty student-apartment sheets, Madeleine finally musters up the courage to say the three fateful words. Her cerebral lover, however, reminds her immediately of Barthes’ statement that after the first admission of love, the avowal has no meaning whatsoever.

Madeleine dumps him almost as quickly as she throws the Barthes volume at his head (good for her), and leaves heartbroken. Leonard, however, ends up far more worse for the wear than she, realizing his mistake shortly before succumbing to psychotic depression.

As in his previous works, Eugenides weaves a tale that moves backwards and forwards in time, prophesying the outcome that his characters will fight for or against. When Madeleine wakes up on graduation day, she is merely hours away from finding out that Leonard has been hospitalized — and from choosing to forgo the ceremony in order to be with him. If the constant interplay between pre-narrative and current events makes The Marriage Plot difficult to follow chronologically, it does allow us to pay particular attention to the three young people whose ideas and emotions are in imminent danger of being exposed to… well, the real world.

After his discharge from the psych ward, Leonard and Madeleine travel to the Cape, where he plans to participate in a fellowship studying the genetics of yeast — an obscure study, the details of which Eugenides shares in almost excruciating detail. Here Madeleine finds herself isolated among mostly males, uncomfortably bridging the gap between her increasingly despondent boyfriend and his colleagues, who must never find out about Leonard’s illness. If anything, his condition has worsened — increasingly reclusive, overweight, and indifferent to her, Leonard proves to be a burden. When Madeleine’s mother and sister come to visit, they find lithium in the bathroom. This discovery throws Madeleine, whose interaction with her parents up to this point pegged her as the favorite, into a position that makes her older sister’s failing marriage as trivial as… yeast. Mrs. Hanna sends Madeleine ominous news clippings in the mail about relationships between manic-depressives and their spouses; meanwhile, Leonard secretly experiments with his dosage, lowering his intake little by little in an attempt to outsmart both his therapists and the disease. Mania slinks in, sullying the edges of his consciousness and, by consequence, Madeleine’s. “It was as if,” she begins to understand, “in order to love Leonard fully, [she] had to wander into the same dark forest where he was lost.”

In a novel where nothing spreads faster than mental disturbances, religious enlightenment creeps at a glacier pace. Mitchell, rebuffed by the woman he believes to be his future mate, departs for Europe in the company of a friend, Larry, with India as his final destination. While in Paris, the two meet up with Larry’s girlfriend Claire, who has been studying feminist theory at the Sorbonne and, comically, hates men. Over dinner, Mitchell finds himself consumed by lust for her and haunted by her accusations that he objectifies every woman he sees.

Since Mitchell weirdly conglomerates the Virgin Mary and Eve in almost every female he sees, this is not far from the truth; however, Claire’s utter inability to recognize her own sexism turns the stay in Paris into a sort of intellectual farce. Mitchell and Claire butt heads on almost every issue, from eating couscous in the Latin Quarter to the way he looks at women when they pass, but it is where their disciplines intersect that Claire becomes hilariously vocal.

"The religion of the Goddess was organic and environmental - it was about the cycle of nature - as opposed to Judaism and Christianity, which are just about imposing the law and raping the land."

Mitchell glanced at Larry to see that he was nodding in agreement. Mitchell might have nodded, too, if he were going out with Claire, but Larry looked sincerely interested in the Goddess of the Babylonians.

"If you dislike a conception of God as masculine," Mitchell said to Claire, "why replace it with one that's feminine? Why not get rid of the whole idea of a gendered divinity?"

"Because it is gendered. It is. Already. Do you know what a mikva is?" She turned to Larry. "Does he know what a mikva is?"

"I know what a mikva is," Mitchell said.

"O.K., so my mom goes to a mikva every month after her period, right? To cleanse herself. To cleanse herself from what? From the power to give birth? To create life? They turn the greatest power a woman has into something they should be ashamed about."

"I agree with you, that's absurd."

"But it's not about the mikva. The whole institutionalized form of Western religion is all about telling women they're inferior, unclean, and subordinate to men. And if you actually believe in any of that stuff, I don't know what to say."

"You're not having your period right now, are you?" Mitchell said.

We laugh, but sense uncomfortably that Eugenides makes a valid point. Mitchell worries constantly about money, becomes distracted during Mass at the Sacre-Coeur, shares a skinny European hotel bed with a stranger. When Claire decides she’s a lesbian, Mitchell and Larry escape from France to Greece, the land of Mitchell’s (and Eugenides’) ancestors. Eugenides insensitively compares Athens to a "giant bathtub filled with dirty suds." Mitchell squeezes his eyes shut and waits to be struck by a lightning bolt of faith at the foot of the Acropolis. We sense that the endless queue of stereotypical personalities that Mitchell meets — a Greek homosexual wearing his shirt wide open to reveal gold necklaces, Evangelical fanatics, traveling lunatics — are not proof that Eugenides is a poor writer, but rather that Mitchell is incredibly judgmental.

Mitchell recalls his time at Brown:

He thought about the people he knew, with their excellent young bodies, their summerhouses, their cool clothes, their potent drugs, their liberalism, their orgasms, their haircuts. Everything they did was either pleasurable in itself or engineered to bring pleasure down the line. Even the people he knew who were 'political' and who protested the war in El Salvador did so largely in order to bathe themselves in an attractively crusading light. And the artists were the worst, the painters and the writers, because they believed they were living for art when they were really feeding their narcissism.

Unsurprisingly, Mitchell is blind to his monumental self-righteousness.

What saves The Marriage Plot from falling into an endless pool of clichés — ah yes, the European jaunt in search of self-discovery, the overly intellectual youngsters jumping headfirst into existential crisis after existential crisis — is the nostalgia Eugenides fosters for a time that is not yet so far away that we cannot remember it, yet completely out of digital touch. We realize, with an indulgent ache in our hearts, that none of this story (in fact, none of Eugenides’ works) could have taken place in the digital age, which is perhaps why he placed them so carefully in the 1970s and ‘80s. Can we understand the almost-mythical traveler’s checks, Mother Teresa sightings, Cold War crazes, and Reagan administrations that he describes? Yes. But we cannot understand the obsession of a generation looking to see or touch information that the average toddler can access today.

The Virgin Suicides was succint and shocking in both execution and subject; Middlesex proved over-indulgent and rambling, faults that we can only forgive in light of its bold investigation into hermaphroditism. Undoubtedly both will age better than his new work, which fades into obscurity next to other brilliant campus novels like Tartt's The Secret History or Wolfe's I Am Charlotte Simmons, to which The Marriage Plot has already been favorably compared. If nothing else, we will turn to Eugenides as an archivist of the '70s and '80s in America, viewed through his kaleidoscope of Greek and Detroit heritage.

Considerably sharpened by the lack of lithium in his system, Leonard makes a move on Madeleine if she but extricates herself from the bed. They have sex almost constantly, a surge of lust that has Madeleine — quite starved of any kind of stimulation — quite manic. She obsesses over his member: "Leonard’s was highly particular to her, almost a third presence in the bed. She found herself sometimes judiciously weighing it in her hand. Did it all come down to the physical, in the end? Is that what love was? Life was so unfair. Madeleine felt sorry for all the men who weren’t Leonard."

Of course, Leonard’s penis merely replaces his manic-depression as the focal point of their relationship; Eugenides allows his characters a hot, sweaty passion that later leads into the most complex and frightening psychotic breakdown Leonard experiences while they are together. Across a dozen oceans, Mitchell volunteers at Mother Teresa's organization, where he wipes fevered brows. Madeleine writes that she and Leonard are going to be married, a letter which — oh, the foreignness! — he picks up at an American Express office and crumples, envelope and all, into the bottom of his backpack.

Is it a coincidence that Leonard, Madeleine, and Mitchell represent three disciplines that claim to explain the universe? I don’t think so. One might even argue that the ease (or lack thereof) with which each of them adapts to life outside the university determines the truth of their intellectual pursuits. Leonard, with biology, occupies what we might see as the colder, more precise side of the spectrum; his mental illness, however, numbs the bold claims of his discipline by laying waste to his mind, body, and consequently his life. Mitchell, whose spiritual search begins at Brown under a particularly astute professor, dreams of God, a dream perhaps conflated with his idealistic love for Madeleine.

Despite his good intentions and his willingness to place himself in locations where enlightenment might be found, Mitchell fails to be compassionate. He enjoys the idea of himself as a volunteer in India, but when he must change bandages and clean up excrement, he balks and runs away. Even Madeleine, whose simply personality may fail to hook the reader, proves herself more moral than Mitchell; she cares for Leonard selflessly until the end. Ever the illusionist, she continually questions truth and morality. While her artistic temperament balances Leonard, it ruins Mitchell, who regards her, as he regards all women, both as feminine perfection and a destructive temptation. Leonard, however, she almost saves.

India's stark poverty, and all the shit and trash that go along with it, stands in complete opposition with the opulence of Leonard and Madeleine’s European honeymoon. The trip is a disaster. In Monaco, Leonard dresses himself in a cape, gambles unrestrainedly with questionable people, basically rapes his wife, and disappears during the night. Madeleine questions their ability to remain together, especially as Leonard's guilt over the occurrence sinks him irretrievably into despair. The Victorian romance for which she yearns had disappeared when marriage was no longer connected to material gain and immaterial gain, as Madeleine and Leonard know only too well, lacks meaning — it lacks a signified. Unquestionably, Leonard benefits the most from their union. But while the idea that the wife brings the true bounty to a marriage seems like a general pat on the back to women, it sucks so much to be a woman in Eugenides' novels that we can’t feel anything but pity for Madeleine. Leonard’s eventual disappearance brings Mitchell running to the rescue, a poor mockery of the Messiah. It isn’t until he can’t satisfy her in bed that Mitchell realizes his mistake, and is consequently enlightened. And after four hundred pages of merely reacting to the mundane cataclysm of her life, Madeleine finally decides to live for herself. Her thesis gets published. The romance ends. She becomes an interesting character.

Of the three, Leonard’s is the most fascinating story, and the one to which the author does the least justice. Michiko Kakutani of the New York Times conjectured that Eugenides modeled his troubled polymath after David Foster Wallace, a radical assumption mostly spurred by the bandana Leonard habitually wears on his head. This absurd claim (which Eugenides denies, by the way) is as exaggerated as Wallace's talent, which exploded into the stratosphere after his death. To compare The Marriage Plot to Jonathan Franzen’s literary attempts is not quite as ridiculous as it is dangerous. Who doesn't wish they could take back the hours they devoted to The Corrections? Eugenides himself is a precarious talent, relying as he does on the siren’s call of our collective youth. In ten years we may not find him as alluring.

Kara Vanderbijl is the senior editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here. She tumbls here. She last wrote in these pages about Breakfast at Tiffany's.

"Let Me Take You Out" - Class Actress (mp3)

"Terminally Chill" - Class Actress (mp3)

"Keep You" - Class Actress (mp3)

THE WORLD

THE WORLD  Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 10:11AM

Wednesday, November 23, 2011 at 10:11AM

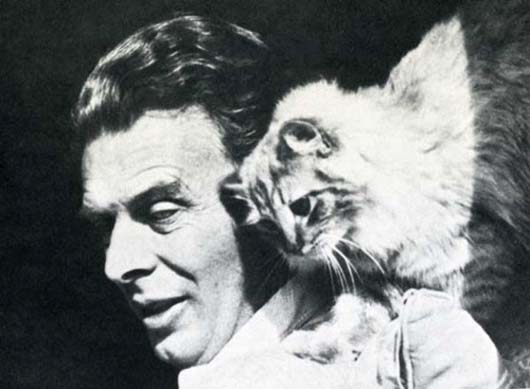

neil gaiman by kelli bickman in 1996

neil gaiman by kelli bickman in 1996 elizabeth taylor

elizabeth taylor

grace kelly

grace kelly

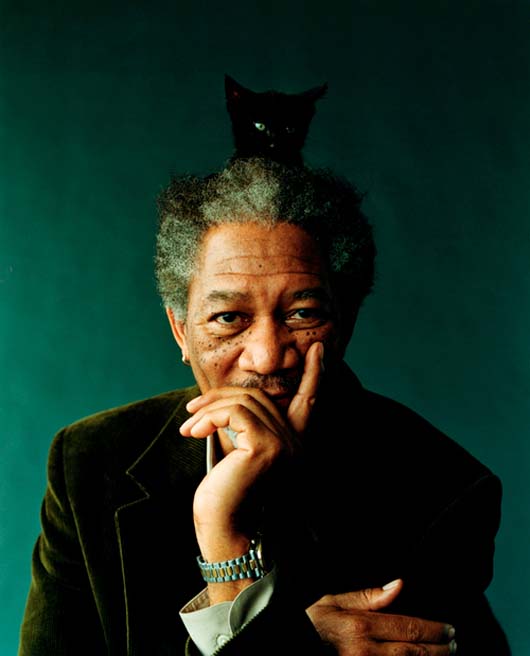

aldous huxley

aldous huxley

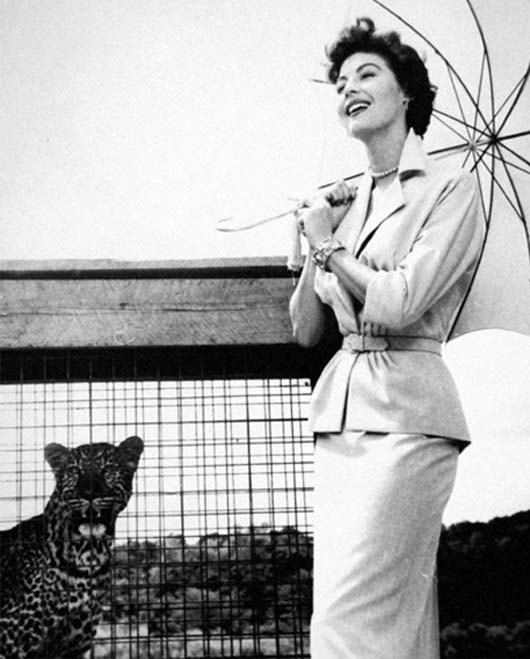

ava gardner

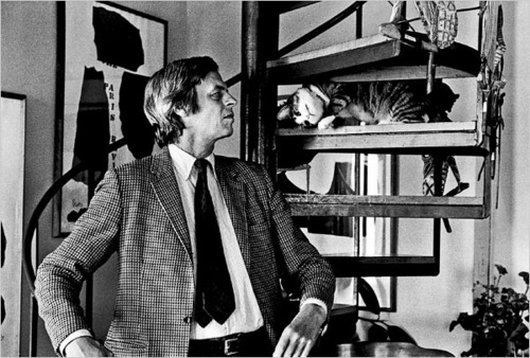

ava gardner george plimpton

george plimpton