TV

TV In Which Downton Abbey Fought In A War

Friday, October 7, 2011 at 10:13AM

Friday, October 7, 2011 at 10:13AM

All Useless on the Western Front

by KARA VANDERBIJL

Downton Abbey

creator Julian Fellowes

War suits Matthew Crawley (Dan Stevens) intolerably well. The first three episodes of the British drama Downton Abbey’s long-awaited second season simply brim over with his bliss. The Western Front of the first World War seems to place a new resolve in him. The discomfort of unwittingly becoming heir to the huge estate of Downton and being shoved into matrimony is forgotten in favor of grander purpose. Not once do we see him weep over his fate. Not once does any blood smear his flesh. He spends approximately two days at the front before returning home on leave, some important duty always on the horizon, always beckoning, always putting him on a train in a wake of weeping women.

Wars and rumors of wars trim away the superfluous like leaves from a hedgerow. Still, the most important query — namely, what will happen to the manor of Downton Abbey if Matthew Crawley perishes in the Great War?! — goes unanswered. The forecasted nuptials between himself and Lady Mary Grantham dissolved into thin air with the possibility of a new heir, yet somehow international bloodshed ensures his inheritance. Nothing but the prospect of a sudden removal from earth will make people fall for you so entirely and forget your country bumpkin ways.

In the interim between Archduke Ferdinand’s assassination and the Battle of the Somme in 1916, Matthew’s eye has settled on a sweet blondish creature, Lavinia (Zoe Boyle) for some reason or another, much to the Granthams' chagrin. They will do everything to investigate the poor girl’s history, not because they feel she is particularly unworthy but because their desire to remain entombed in Downton is strong. As Matthew slips from their fingers into the spoils of military command, the promise of their continued legacy at the mansion begins to fade. Matthew, for his part, seems nonplussed by Lavinia except as a concept to move towards while halfway underground with hundreds of dying men.

Indeed, Gosford Park scribe Julian Fellowes wastes no time taking us to the trenches; they divide both France and portions of Downton’s halls as differences brew between servant and master, servant and servant, and master and master. As it is, the pandemonium of the front can only translate to the genteel English countryside as a prevalence of raised voices, as maids serving the supper instead of footmen, as nearby buildings transforming into hospitals for the wounded. The residents must adjust in their own ways to a rapidly changing environment: some making their sacrifices willingly others grudgingly letting go of what has always been. Reluctance strains on both sides, but it is surprisingly the servants of Downton who have more trouble accepting the change.

Power always remains in some form, but those who live on the penny of power quickly become obsolete.

Downton Abbey houses three types of servants: those who aspire to be more, those who are more, and those who don’t care. The new housemaid, Ethel (Amy Nuttall) entertains delusions of grandeur although she doesn’t have the presence of mind to know when she is being made fun of. Chauffeur Tom Branson (Allen Leech) believes in the socialist ideal and will do anything to be heard. Men like the valet John Bates and the butler Mr. Carson sacrifice their own health and happiness for the sake of the Granthams and their family honor. Of all the characters, culturally we are the least like them, and the most like Ethel, insisting that the best be set aside for her.

Many men have gone to war, but not all. The Earl of Grantham balks at being too old to join the ranks at the front while the eager young footman, William (Thomas Howes), does not understand why his father will not let him enlist. A white feather is enough to send a man blazing in injured pride to his death, but it will take a greater sacrifice to bring him home again.

When Downton footman Thomas deliberately gets himself shot in the hand, he incapacitates himself not only in his role as soldier but also in his former role as servant. Henry Lang, the Earl’s new valet, suffers from shell shock and commits a series of humiliating blunders before they finally let him go. We must imagine that some men returned home relatively sound of mind and body, but they are perhaps more useless to the stories of horrific war than are the millions of mute bones lying beneath Verdun.

And what of the women? The Countess Dowager (the elegant and familiar Maggie Smith) continues to fix flower arrangements, ones that ominously resemble funeral wreaths. Lady Grantham holds Downton Abbey in patient hands, obviously conflicted between a desire to serve the cause wholeheartedly and to hold on to remnants of a fading world.

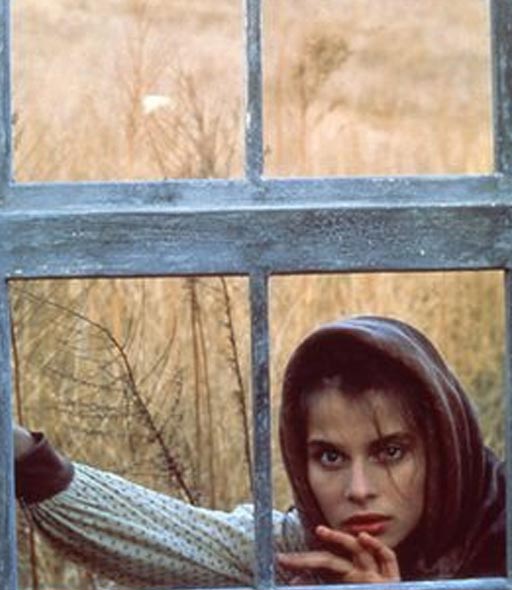

Matthew's mother Isobel Crawley (Penelope Wilton) continues to baffle and exasperate all with her bluntness and her attempts to control. When she encourages Sybil to become an auxiliary nurse, Lady Grantham and the Earl hesitate — but accept their daughter’s need to prove useful. Because she is the middle daughter, her whims are neither regulated nor overly indulged; while Mary must continue to uphold family honor and custom by searching for a suitable mate, and Edith suddenly and wildly volunteers to drive a tractor at neighboring farm, Sybil’s decision goes unquestioned. Without the familial duty to protect honor or the reckless impulse to gain recognition, she sails through uncharted free territory. She lives in no man’s land.

We tend to glorify ourselves when we imagine the past, taking for granted that we would be kings and queens, clean and fat and absolutely without disease. Most importantly, we would be on the right side. But history has no sides — only truth, untruth, and that vast shell-shocked territory in between. When Thomas lifts his lighter, trembling, over the lip of the trench, he’s not only gambling with gangrene and death but also his sense of identity. A man can put on a footman’s livery and still not be a footman, and he can put on fatigues and be a soldier for a while until he’s wounded. What is Thomas, when he returns to Downton? Nobody has tried on as many uniforms for size.

I am reluctant to call him the archenemy of Downton Abbey, but not as reluctant as I am to believe that the middle daughter, Lady Edith (Laura Carmichael) will set aside whatever petty competitiveness drives her and find a healthy niche in the world. One can hardly imagine a more fertile place for a young woman to bloom than on a farm in early twentieth-century England, but Edith foils her own attempts to be useful during the war by getting involved with the married farmer whose tractor she helpfully drives. The more she attempts to set herself apart from her sisters, the more she resembles Mary, whose own desperate attempt to forget Matthew leads her to court a man with a disturbing lack of eyebrows (Iain Glen). No other family in television has worked so disharmoniously on a common cause.

Kara VanderBijl is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Chicago. She last wrote in these pages about Roman Polanski’s Tess. You can find her website here. You can find an archive of her writing on This Recording here.

"Bittersweet Melodies" - Feist (mp3)

"The Circle Married The Line" - Feist (mp3)

"The Undiscovered First" - Feist (mp3)