BOOKS

BOOKS In Which Here Are Novels Finer Than Any Imagined

Wednesday, March 9, 2011 at 11:57AM

Wednesday, March 9, 2011 at 11:57AM

Our Novels, Ourselves

Almost everything is a matter of taste, even criminal acts. Taste rules dreams, sexual profligacy and buying power. Haven't you seen High Fidelity? Novels are the ultimate arbiter of taste, for there is truly nothing that they cannot contain under the right circumstances. Tomorrow we issue our 100 Greatest Novels list, where we will examine those novels which most fully represent the feeling of life. As preparation, we asked a few young writers and artists to list their favorite novels. This is the last in a three part series.

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Elisabeth Donnelly, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Alexis Okeowo

A Wrinkle in Time by Madeleine L'Engle

This book is technically a children’s novel, but I usually believe that children’s books are the most appealing and universal. It’s a story about time travel – one of my all-time favorite subjects! – and finding your moral strength and trusting your abilities. What struck me about A Wrinkle in Time, even as a kid reading it for the first time in my backyard in Alabama, was how intelligent and layered the writing and plot were, and how enthralling this galaxy was that L'Engle created. I couldn’t stop dreaming about falling into her worlds.

Half of a Yellow Sun by Chimamanda Adichie

This book was the only time I’ve read a novel that reminded me of my life experiences so much it was kind of excruciating at some points. The pain aside, Half of a Yellow Sun is the best example of grand, lyrical storytelling I've ever seen. The novel is set during the Nigerian civil war, and is a story both about struggling to live with compassion and dignity during chaos, and about a love affair that consumes a British journalist and two Nigerian sisters.

What is the What by Dave Eggers

I think I swooned at the first point in the novel when Eggers started writing from the perspective of the South Sudanese protagonist: the diction and the tone were perfect and reminiscent of the regal, funny Sudanese people I knew in Africa. The story about the Lost Boys (and girls) of Sudan is incredibly sad, yes, but the writing is so beautiful and the voice of Valentino Achak Deng so important, that I didn’t mind. What is the What ravaged my emotions, but in a good way.

Alexis Okeowo is a writer living in New York. She is an editorial assistant at The New Yorker. You can find her website here.

Benjamin Hale

These aren’t necessarily the books I would take with me if I were banished to a desert island; there’s no point, I know them too well. These are three of the books that have most profoundly changed me, changed my understanding of literature, and changed the way I want to write.

The Tin Drum by Günter Grass

Kurt Cobain, with characteristic self-loathing, once described "Smells Like Teen Spirit" as “basically a Pixies rip-off.” If there’s a book to which I would happily acknowledge a personal debt with such groveling humility, it would be this one. My own novel is basically a rip-off of The Tin Drum. The Tin Drum is among the bravest books ever written.

The Adventures of Augie March by Saul Bellow

Henderson the Rain King is a better book, and I thought of listing it instead, but I chose Augie March because it was the first Bellow book I read, and the one I set out to study, in the way an apprentice chef might try to reverse-engineer a mystery sauce by taking sips and altering ingredients accordingly, trying to discover how the master made it. I lent my copy to a friend recently, who told me I’d apparently circled a certain paragraph and wrote in the margin, "LEARN HOW TO WRITE LIKE THIS."

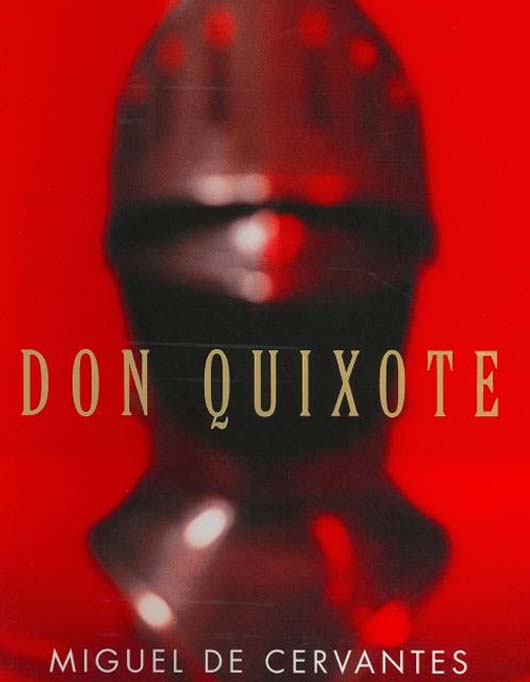

Don Quixote by Miguel de Cervantes

Arguably the first novel and, I would argue, the best. To me, the Man of la Mancha represents the spirit of the novel: comedy in the front, tragedy in the back. It is a story that begins, but never ends.

Benjamin Hale is a writer living in New York. He is the author of The Evolution of Bruno Littlemore.

cover by joshua k. marshallRobert Rutherford

cover by joshua k. marshallRobert Rutherford

Let me first assume a male audience. The books that you read in your angry youth tend to remain after the emotion they engender fades. Though the blueprint lightens, you realize the man you thought you'd become are also the men the authors wanted to be, but weren't. The three imaginary men I thought I'd become but lacked the conviction are:

The Sun Also Rises by Ernest Hemingway

Hemingway wrote his first novel "not to be limited by the literary theories of others, but to write in his own way, and possibly, to fail." At least when he was young, he lived a life more full. It's easy to romanticize Ernest driving an ambulance in World War I and defining the lost generation in Paris, but it's easy because he actually did those things. No one should be allowed to write anything until they are seriously wounded in a war at least once. Hemingway shot himself in the head with a double barreled 12-gauge shotgun at his home in Ketchum, ID.

Tropic of Cancer by Henry Miller

Fifty years before you were born, Miller put to words everything you have ever wanted to do in your life but you can't because you are too weak, afraid and lazy. He fucked his pen across Paris, and then raped New York in Tropic of Capricorn. Jack Kerouac was an aimless hobo in comparison. Miller died in the Pacific Palisades and his ashes were scattered off Big Sur.

The Rum Diary by Hunter S. Thompson

A novel by an alcoholic before he became a drug addict is the best reason for sticking to alcohol. There's very little in this book of the Hunter caricature that came later, so it feels like a the work of a different author, the caterpillar before the cocoon. It's laconic instead of hyper and helps you realize that before he was a gonzo journalist he was just a kid who idolized Jack Kerouac. Thompson shot himself in the head with semi-automatic Smith & Wesson 645 at his home in Aspen, CO.

You wake up one day and you're happy, and you don't want to kill yourself. And that's depressing because it means you can't be a writer. To the men we became, and the authors who showed us how not to become them.

Robert Rutherford is a writer living in Los Angeles.

Kara VanderBijl

Madame Bovary by Gustave Flaubert

This book, which I believe I have read at the turn of each season since I first discovered it, inspires in me a strange mixture of nausea and awe. Flaubert's mastery of the French language remains the standard by which I measure my own understanding of it; his sad lady protagonist remains my greatest fear and a faultless mirror. Emma, c'est moi.

The Go-Between by L.P Hartley

One must disregard the fact that Hartley's opening line is now as over-quoted as a Frost poem in order to appreciate its truth. I treasure this story as a sort of secret garden, uncomfortably recalling the innocently ignorant period of my childhood. Plus, since this novel is ridiculously under-read, I have the pleasure of relating its poetry to anybody within earshot.

The Name of the Rose by Umberto Eco

Eco wooed me by quoting Latin and refusing to translate it on virtually every page. In other words, this medieval murder mystery occupies the Read This And Understand Your Humanity shelf, a black hole of disproportionate presumption. A category of people, to which I belong, will read it and take pride in the fact that they grasp very little of the universe. It was not written for them.

Kara VanderBijl is a writer living in Chicago. You can find her website here.

Damian Weber

Love Medicine by Louise Erdrich

After reading too much, and writing three of your own unfinished novels, you can't read fiction anymore. Sure you can mine for ideas, but mainly your bullshit meter won't let you finish 20 pages. That's why we only read non-fiction now. Or Louise Erdrich. She never sets off my bullshit detector. On a different topic, we need to write more short stories.

Hyperion by Dan Simmons

After you're done reading all the best literature in the world, you get over it, and move on to genre fiction. Especially if you want to write yourself, and you're sick of being limited by your own boring imagination. Did you know you were as imaginative as Dan Simmons? Did you know you could break free and write the craziest awesome shit?

Trout Fishing in America by Richard Brautigan

If all my favorite music lyrics could be assembled in a narrative of my life with the girl I like and our daughter, I would read it over and over like I do Trout Fishing In America.

Damian Weber is a writer and musician living in New York.

Jessica Ferri

The Loser by Thomas Bernhard

Do you hate everything but have a great sense of humor about it? Read Thomas Bernhard for all your obsessive, misanthropic, neurotic, suicide-inducing rants. Because really, when all you want to do is play piano but Glenn Gould studies at your music conservatory, what the fuck is the point of living except to complain about it?

Franny and Zooey by J.D. Salinger

Over a lunch of Frog Legs and an uneaten chicken sandwich, Franny realizes that she's surrounded by "section men," and needs to ceaselessly pray. Zooey, her actor brother, after a long marinade in the tub, calls her from the living room to tell her about Jesus and the Fat Lady. You will read this dialogue and you will laugh. This will be followed by a tightening in the chest.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë

Jane Eyre is the book in your middle school "media center," that calls to you with the intense-looking girl on its cover and the author's familiar sounding last name. You might want to make it a re-read past the age of nine, however, because Jane Eyre is one of the greatest novels ever written, and you'll need to have loved and lost and been "poor, obscure, plain and little," to fully understand how awesome it is for Jane to bust up out of a terrible situation in 1847 and go traipsing through the English rain, risking pneumonia and God knows what else to become the best narrator any reader could ask for.

Jessica Ferri is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Britt Julious

The Secret History by Donna Tartt

My body shakes thinking of the characters in The Secret History. I don't think I've despised characters so succinctly and passionately. The longer I think about the plot and the characters' decisions, the more incensed I become. But never have I had such immense, perhaps even overwhelming pleasure reading a book. Characters that challenge me this much only remind me why I love reading.

The Dud Avocado by Elaine Dundy

The Dud Avocado is a whip-smart little gem of a book, one that I've read three times in the few months since I've finished it. Sally Jay is young and silly and tricky. I relate to her almost selfishly: I hate knowing that other people will read thus book and see themselves (flighty, sarcastic, anxious) reflected from line to line. I'd like to believe that Sally Jay and I are kindred spirits, and that everyone else is just pretending to know what it's like to be us.

Nightwood by Djuna Barnes

Djuna Barnes' writing is lush. Its lushness makes me wince, for I can only dream to write as uniquely and profoundly as she did. There are certain passages I've underlined and like to revisit from time to time. My masochistic nature breaks free; reading her work is torture for the young writer who only wishes to capture a portion of that indescribable quality each page possesses.

Britt Julious is a writer living in Chicago. You can find her website here and her twitter here.

Letizia Rossi

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald

Sometimes you just want to get the fuck out of New York. Get away from the bullshit, the social climbers, the sycophants and just head back to your home town. You're tired of getting wasted, open bars, not even knowing whose party it is; the antics of bankers, bohemians, socialites; conversations about ‘content’, banal proclamations, networking, feigning interest, working hard to get ahead. These assholes are all just spending their Daddy's money anyhow. I mean does anyone even really love anyone or is it just what they represent?

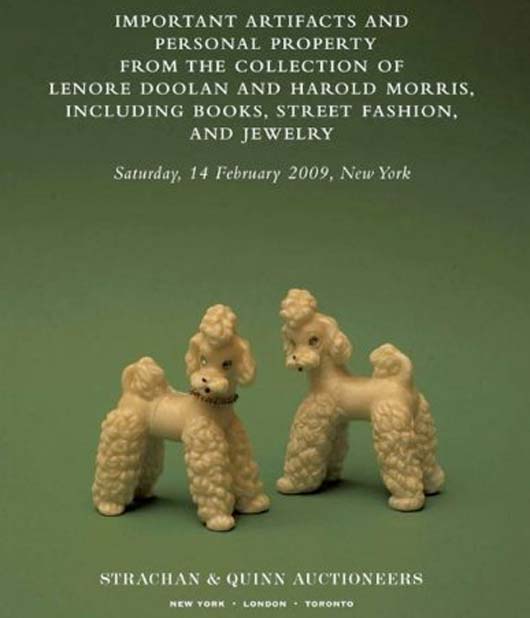

Important Artifacts and Personal Property from the Collection of Lenore Doolan and Harold Morris, Including Books, Street Fashion, and Jewelry by Leanne Shapton

My ex-boyfriend had the best stuff, amazing stuff, the stuff of dreams: LPs, 70s era McIntosh receivers, silk velvet chaise lounge, arts and crafts desks, criterion dvds, vintage file cabinets, Godard posters, fiestaware, le crueset, butter bell, sheets that – somehow tastefully – match the towels, William Eggleston books, walnut bookshelves filled with every book you’ve meant to read (arranged by color), a ship in a bottle, vintage Fernet Branca ad /(souvenir from trip to Buenos Aires). Does anyone really love anyone or is it just what they represent?

The Secret Diary of Adrian Mole Aged 13¾ by Sue Townsend

Accept no imitators! This is the genre-defining self-deprecating epistolary diary novel. (Not mad at you Bridget Jones and Nick Twisp.) SPOILER ALERT: "Love is the only thing that keeps me sane..."

Letizia Rossi is a writer living in Williamsburg. You can find her website here.

Will Hubbard

Justine by Lawrence Durrell

I am drawn to books that present an unthinkable world. A world that it would be impossible for me to inhabit because of my limitations. A world in which my head would explode. Such is the mercy of a great novel – that it only partially explodes our heads, privately and pleasurably. The Alexandria of Justine is a place where the colors of the sky and water are not colors you've ever seen before. And the politics of the place – both municipal and sexual – are impossible to understand and thus easy to enjoy. Every character constitutes a nation unto him or herself – there are cryptic alliances and yes, a great deal of sex, but eventually everyone stands (or dies) alone. Nobody prevails. Alexandria prevails. Durrell felt that he needed to write three sequels to explain away all the misery and intrigue of Justine – I would have preferred that he didn't. In fact, I've never read Justine all the way through – and still, somehow, it's my favorite book. Explain that.

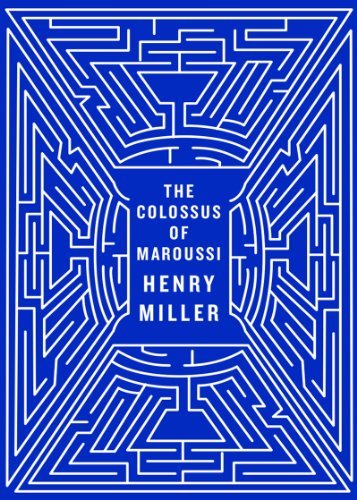

The Colossus of Maroussi by Henry Miller

Everything I said above, subtracting the abundance of sex and adding long, rich passages about the qualities of the light at various Greek archaeological sites. I know that strictly speaking this is not a novel, but when a human being has the experiences Henry Miller did and can process them with the grace that he does in this book – there's nothing to really delineate it from fiction. If a novel is a long story that didn't happen, then Colossus for all intents and purposes is a novel – it simply could not have happened. Again, our limitations. The most sensitive of us is far too dull.

A Fan's Notes by Frederick Exley

The narrator of this novel loves football, specifically Hall-of-Fame Giants running back Frank Gifford. It's an easy enough world for some of us to imagine – long Sundays in dark, cool, damp places checking alternately the score on the television and the amount of beer in our glass. But sport only frames Exley's story of human weariness and wariness which, again, gives me supreme pleasure because I cannot imagine surviving the mental circumstances of its narrator. That the protagonist shares his name with the author we forgive because the book draws heavily – some say absolutely – from the real Frederick Exley's life, which at times was more horrific than anything in his 'fictional memoir.' Punctuated liberally by the arrival of white-clad men from mental institutions, A Fan's Notes manages a steady undercurrent of hope; I doubt its author ever could.

Will Hubbard is a writer living in Williamsburg. His first book of poetry, Cursivism, is forthcoming from Ugly Duckling Presse in April.

Durga Chew-Bose

Adolphe by Benjamin Constant

“Nearly always, as to live at peace with ourselves, we disguise our own impotence and weakness as calculation and policy; it is our way of placating that half of our being which is in a sense a spectator of the other.” Forgoing traditional imagery, Benjamin Constant’s Adolphe is furnished instead with emotions, “sleepless nights,” and mood. Sober stuff, yes, but a fortune of maxims, I promise! Rumored to be based on Constant’s liaison with Madame de Staël, the plot is classic: a doleful and somewhat reclusive young man, seduces a Count’s lover. Their affections grow alongside the young man’s doubts and eventually, desire’s cruel law of diminishing returns overcomes. While short — less than a hundred and fifty pages — I suspect Adolphe has become my skeleton key; that which can unlock, or at the very least let breathe (read: indulge in!) some of my most pressing reservations. For anyone who is preoccupied with feelings, especially love, this novel is a trove of its articulations, both physical and mental.

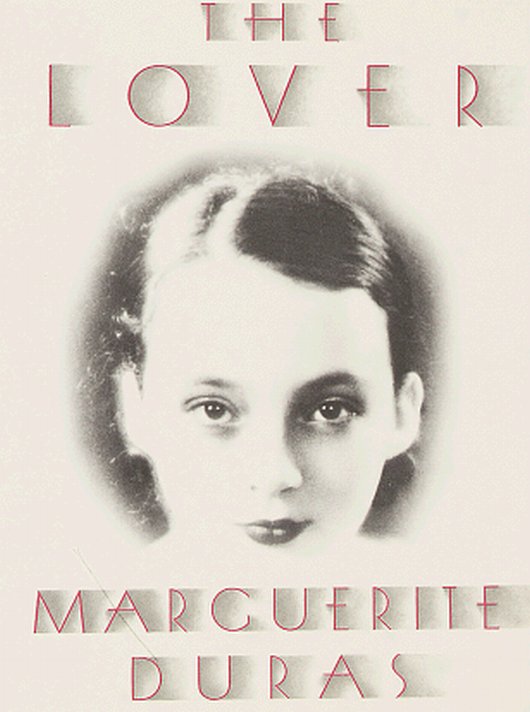

The Lover by Marguerite Duras

Marguerite Duras’s The Lover is best read over the course of one day. It possesses you. And like on especially hot summer afternoons where the sun's heat appears to be coming from inside you, Duras’s prose spawn that similarly sublime and somewhat punch drunk sensation from having sat outside for too long. My copy of it is worn, underlined, scribbled on, and yet, it still smells new. I refer to it not only for the story of the unnamed pubescent protagonist and her lover, but for the descriptions of women, like Hélène Lagonelle, who are "lit up and illuminated," (unlike the men who are "miserly and internalized.") That addled mix of envy and adulation—of knowing the nude shape of your friend’s body even when she is clothed, the convex, the concave, of using words like 'roundness,' 'splendor,' and 'illusionary' and then following them with words like, 'never last,' and 'kill her' — confirm the novel’s overture, a sentence that I copied over and over in my notebook what feels like years ago, unaware of its enduring potency: “Sometimes I realize that if writing isn't, all things, all contraries confounded, a quest for vanity and void, it's nothing."

Moby Dick by Herman Melville

I care deeply about this book because it pools together so many thoughts that for so long I assumed were separate. It reads like trinkets in constant orbit, like "that enchanted calm which they say lurks at the heart of every commotion." It's also terribly funny, diagnostic, and warm; the finest combination! One of my favorite chapters, 'The Tail,' begins with this: "Other poets have warbled the praises of the soft eye of the antelope, and the lovely plumage of the bird that never alights; less celestial, I celebrate the tail." I simply cannot get enough.

Durga Chew-Bose is the senior editor of This Recording. She tumbls here and twitters here.

Rachel Syme

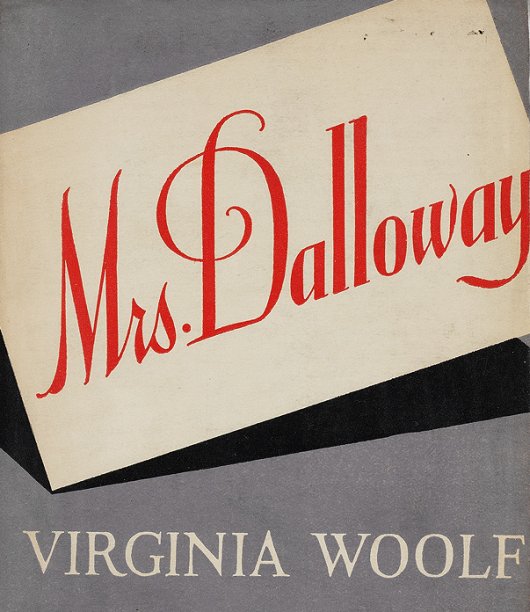

Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf

I am not ashamed to say that I loved the film adaptation of The Hours — if only for that twitchy Philip Glass score and to see Meryl Streep wring her hands and cry on a kitchen floor covered in egg yolks (I prefer this flustered Streep to the daffy Nancy Meyers version who makes croissants stoned) — but I do understand the bit of damage that the film and the book that spawned it did to the venerable cultural status of Mrs. Dalloway. Not that the The Hours didn't do Woolf justice; it's just that one could get the impression that it's not entirely necessary to go back and read the source material. The essence is there in the film, it's infusing the whole thing. Which is all fine! But if you have a deeper interest in writing, or women, or parties, or human frailty, or moral quandaries, or in passions v. the banal scutwork of daily life, then I would prescribe the original to you like a tonic. Reading Clarissa's inner monologue, her incantations about all of the things she can never have, that life will never be for her; this is how I learned that writing born from empathy just feels different, and those that master it are sorcerers.

Anagrams by Lorrie Moore

A small but important truth to get out of the way first: As a novel, Anagrams is kind of a disaster. Other novels likely talked some shit about it in the hallways, wondering why it had to come to class so grubby and loose and patched together. The book is — if we want to get technical about it — closer to a novella that has been smashed together with a few short stories and sealed with word pectin. Each little fragment features characters with the same names (Gerard and Benna) and a few overlapping characteristics that carry over between story breaks, but the flow is not immediately scrutable or consistent; it lumps along. And I couldn't love it more. As is the case with most things that get slammed into lockers at first, Anagram is a slow burner, this late bloomer of a book that takes some time and investment to blossom on you. It is a White Swan willing to twirl overtime with an Odile inside. I get more out of re-reading this book than I do most any other, if only because I think it's the funniest and harshest and loneliest Moore has ever been on the page, and her talent for owning that particular literary trifecta is well-documented. In an interview with The Believer, Moore said that she wrote Anagrams "longhand on a typewriter, and it probably contained more crazy solitude than any other book I've written." And she's right! It's a crazy lonesome read. But also, there are these glittering moments of warmth that peek through, sharp enough to break the skin: Life is sad; here is someone.

The Debut by Anita Brookner

"Books about books" is a genre that is usually best avoided (unless you find great pleasure in watching someone try to high-five himself), but Brookner's story about Ruth Weiss, a 40-year-old Balzac scholar who, in the first line, discovers that "her life had been ruined by literature" is rich and savory, and magically absent of cliche. The book moves ever so slowly, as Ruth reflects on lessons from her youth ("moral fortitude…was quite irrelevant in the conduct of one’s life: it was better, or in any event, easier, to be engaging. And attractive.”), on her selfish childhood and one terribly broken love affair, and on how she came to be an academic loner writing a neverending study of Women in Balzac's Novels. Ruth's story has an Olive Kittredge sheen to it, in that not much happens outside of a lonely woman's meanderings through her own life, and yet it has a British crackle to it, and a tender pacing that could only belong to a mature writer. Brookner published The Debut — her debut — when she was 53 years old, and you can immediately tell that the prose comes from the mind of someone who has done some living and losing and mellowing and accepting, and is on that phase of the roller coaster where your jaw is settling back in. I read this when I want to feel like I am consulting an swami of calm; oracular spectacular, a soothing voice that also tells you how to live.

Rachel Syme is the books editor of NPR.org. She tumbls here and twitters here.

Amanda McCleod

The Brothers Karamazov by Fydor Dostoyevsky

Poor Fydor! Poor Dmitri! Poor Ivan! Though their fates may have been brutal it is Alexey Karamazov I feel the sorriest for! Fated to be Dostoyevsky's great protagonist in a second novel which he failed to complete within his lifetime. Alexey Karamazov is my favorite character of all time, easily. He appears to be modeled after saints and folk heroes alike, and is possessed with a bottomless kindness that is shocking in contrast to his own father's maniacal meddling. What I would give for that second book to have been completed! I had the great pleasure of reading The Brothers Karamazov along with a few friends in recent years and together we fostered the notion that everyone is at heart one of the three brothers: The realist Ivan, the impassioned Dmitri, or the gentle Alyosha. We hope no one we encounter is a Smerdyakov or Fydor, and we've all met our fair share of Grushenkas. I've loved an Ivan and befriended many Dmitris, but I'll always be an Alyosha.

Stranger In A Strange Land by Robert A. Heinlein

Heinlein captivated the world so thoroughly with Michael Valentine-Smith, the man from Mars, and his concept of Grokking that "Grok" has been incorporated into the English language. From the novel itself: "Grok means to understand so thoroughly that the observer becomes a part of the observed." Since first reading Stranger I've held this notion in the back of my mind whether encountering art or others. I can honestly say that I never expected I would encounter such a earnest concept in a work of science fiction, yet Heinlein achieves many such beautiful instances as this one continually throughout the novel. At times this read can be campy, but that really only adds to the pleasure of examining humanity through the eyes of a man reared in martian culture.

Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Friedrich Nietzsche

For one thing I can't think of a week since I've read this book that the Eternal Return hasn't crossed my mind. It is a horrifying thought, that is unless you live with such conviction that you reach Amor Fati. If you were doomed to repeat all of your days eternally, could you stomach living them? This is the sort of thing I'd like to wake up and worry about every morning, though often I am most worried about where caffeine will come from and how soon it will come. Thus Spoke Zarathustra was extremely enjoyable for me to read, but this is surely because it mimics the New Testament in style. As a product of catholic school it was actually very comforting to be reintroduced to this sort of language when I first read this novel. This quickly became extremely amusing, as Nietzsche's eccentric Zarathustra verges on zealotism often and backhanded critiques against religion are delivered feverishly. If you haven't delved into Nietzsche before I'd say this is a fun place to start.

Amanda McCleod is a writer living in Brooklyn. You can find her website here.

Yvonne Georgina Puig

All My Friends Are Going To Be Strangers by Larry McMurtry

Larry McMurtry is pretty much my hero. He's one of the most productive and least pretentious writers around. This is a beautiful, hilarious story written in clear, simple McMurtry style, and much of it is set in Houston, Texas, my hometown. Not many novels are set in Houston because generally speaking it's an uninspiring place. But this book, along with Terms of Endearment, make me nostalgic for oppressive humidity and flat urban sprawl and larger-than-life hairdos. I don't enjoy writing book reviews (unless I love the book I'm writing about), or analyzing books to pieces. I just enjoying reading, and then enjoy loving the books that I love, if that makes any sense. McMurtry is easy to love in this way because he tells such great tales. Three summers ago, I started it on a hot day in Austin, Texas, a few miles from where the book opens.

A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley

I love books populated by characters from Sarah Palin's "real America." Their problems are less self-indulgent and more insidious. "Real" Americans, in my opinion, are much more interesting than people from, say, Santa Monica. A Thousand Acres, an incredibly poignant and masterful first-person re-imagining of King Lear, set on a farm in the Heartland, is really a story about a family confronting evil. Yet everywhere you turn someone is baking blueberry muffins, or fixing coffee for the pastor, or making a casserole for the church social. Smiley gives you a slow drip of Godly politesse, and then suddenly you're drowning in utter devastation. I think this is how darkness really functions.

Lady Chatterley's Lover by D.H. Lawrence

A friend who recently graduated from Columbia told me she took a class there on D.H. Lawrence which was full of Lawrence detractors, and apparently there's this whole faction of them out there in the world, who go around disputing Lawrence's reputation as one of the greats. Maybe this is a known thing, but not to me, and I'd like to tell those people to shove it. It's enough that Lawrence wasn't treated very kindly while he was alive. These haters would be lucky to describe a flower just once as beautifully as Lawrence described flowers all his life. We need more writers in love with flowers, who find faith in nature, and who remonstrate the vulgarities of the world. Thank goodness for Lawrence's sensitive, deep-seeing soul. I love all his books, but I think Chatterley is his strongest narrative, and a good place to start in reading his work.

Yvonne Georgina Puig is a writer living in Los Angeles. You can find her website here.

Our Novels, Ourselves

Part One (Tess Lynch, Karina Wolf, Elizabeth Gumport, Sarah LaBrie, Isaac Scarborough, Daniel D'Addario, Elisabeth Donnelly, Lydia Brotherton, Brian DeLeeuw)

Part Two (Alice Gregory, Jason Zuzga, Andrew Zornoza, Morgan Clendaniel, Jane Hu, Ben Yaster, Barbara Galletly, Elena Schilder, Almie Rose)

Part Three (Alexis Okeowo, Benjamin Hale, Robert Rutherford, Kara VanderBijl, Damian Weber, Jessica Ferri, Britt Julious, Letizia Rossi, Will Hubbard, Durga Chew-Bose, Rachel Syme, Amanda McCleod, Yvonne Georgina Puig)

If You're Not Reading You Should Be Writing And Vice Versa, Here Is How

Part One (Joyce Carol Oates, Gene Wolfe, Philip Levine, Thomas Pynchon, Gertrude Stein, Eudora Welty, Don DeLillo, Anton Chekhov, Mavis Gallant, Stanley Elkin)

Part Two (James Baldwin, Henry Miller, Toni Morrison, Kurt Vonnegut Jr., Margaret Atwood, Gertrude Stein, Vladimir Nabokov)

Part Three (W. Somerset Maugham, Langston Hughes, Marguerite Duras, George Orwell, John Ashbery, Susan Sontag, Robert Creeley, John Steinbeck)

Part Four (Flannery O'Connor, Charles Baxter, Joan Didion, William Butler Yeats, Lyn Hejinian, Jean Cocteau, Francine du Plessix Gray, Roberto Bolano)