BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Are Open For Breakfast

Wednesday, September 19, 2012 at 10:18AM

Wednesday, September 19, 2012 at 10:18AM

Travelling

by MARY OPPEN

from Meaning: A Life

The people I see and talk to, the ways they earn their livings, the children I watch, the courting customs, the ways of parents with their children are all to me learning, and I re-evaluate my own ways and my country's ways every time I travel.

It is not comfort, ease, or previous knowledge that takes me travelling; travelling is never as comfortable as being at home, and I am thrown out of my accustomed style and habits on meeting situations and people for whom I have no preparation.

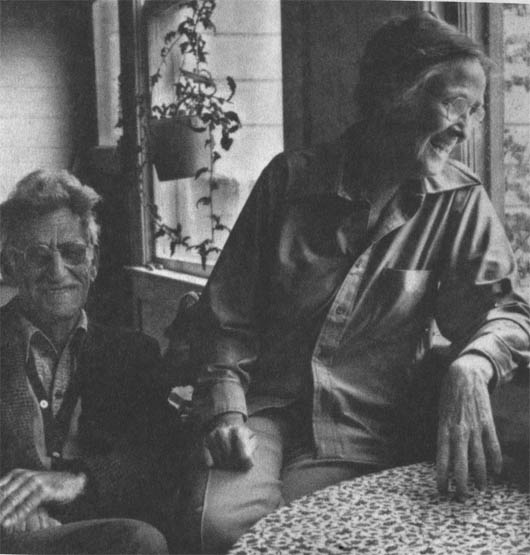

George and Mary Oppen, Long Island Sound

George and Mary Oppen, Long Island Sound

I think I go travelling in order to be jostled and jolted and confronted with the necessity of thinking faster to meet fast-changing occurrences. Happiness comes in the conversations and the learning that I have to master, even in the barest knowledge of how to get from here to there. It is culturation simply to gain insight to yet one more country or city I never saw before; if I do not learn it well, at least I meet it freshly at the moment I confront it.

In Paris the Impressionists were not yet all dead; in 1930 even their art was not yet in the old established museums, and we went to a private gallery to see Picasso's latest show. I noticed Picasso himself watching us to see our reactions to his paintings, which were the first I had seen of women distorted into their social and emotional meanings, beyond the portraits of previous times. Meanings which were painful to accept I later found to be profound class judgments and beautiful in new ways, in their colors and design. After seeing these portraits, women on beaches and bourgeois women in cafes had a different meaning, in which Picasso had caught and held them. His contribution of fifty years as a painter, most of which time I have been alive, has put him on a list of those who will speak for us to a future time.

George and Linda Oppen in Detroit, 1942

George and Linda Oppen in Detroit, 1942

Apprehension mixed with elation as we disembarked at Baltimore and began the drive to New York City. As we approached the first stoplight, grown men, respectable men stepped forward to ask for a nickel, rag in hand to wipe our windshield. This ritual was repeated every time we paused, until we felt we were in a nightmare, our fathers impoverished.

Manhattan loomed across the New Jersey flats; it grew into pinnacles as sunset lit the windows, and we entered the long tunnel under the Hudson River. In Brooklyn we rented an apartment on Willow Street, the first of many apartments we have lived in at one time or another in that same neighborhood of Brooklyn Heights.

George Oppen with Harvey Schapiro

George Oppen with Harvey Schapiro

Louis Zukofsky, the slender dark young man, sloping along on his long stalk-like legs, head forward, shoulders hunched, a little close-visored cap on his head. Louis so delicate I didn't think he'd live out five more years, Louis in my mind associated with his own Mants.

But as his long life has proven, Louis is hardy, more hardy than we knew. He has survived with Celia, refusing the attentions of the young who have come admiring him and his place in poetry. He survives, perhaps strengthened by his bitterness and feeling that he must be the only poet or he will not accept acclaim. Louis had not been to Europe; he had only corresponded with Pound. The problem was that Louis had no money; the trip required that Louis' friends help to pay his way. Somehow this was done, and several of us made contributions.

Lorine Niedecker

Lorine Niedecker, a student of Louis' at the University of Wisconsin, followed him to New York; we invited her to dinner, and after waiting for her until long after dinner-time, we ate and were ready for bed when a timid knock at the door announced Lorine. "What happened to you?" we asked.

"I got on the subway, and I didn't know where to get off, so I rode to the end of the line and back."

"Why didn't you ask someone?"

"I didn't see anyone to ask."

New York was overwhelming, and she was alone, a tiny, timid small-town girl. She escaped the city and returned to Wisconsin. Years later we began to see her poems, poems which described her life. She chose a way of hard physical work, and her poetry emerged from a tiny life. From Wisconsin came perfect small ms of poetry written out of her survival, from the crevices, that seeped out into poems.

Walking with Louis when Discrete Series was in manuscript, George was discussing it with him before showing it to anyone else. Louis turned and with a quizzical expression asked George, "Do you prefer your poetry to mine?"

"Yes," answered George, and the friendship was at a breaking point.

We went exploring with our friends Mary and Russel Wright, through the East Side of the city where lines of drying clothes festooned the area-ways and back yards of the tenements. Fruit stands and vegetable stands and wagons drawn by horses were piled with heaps of color created by oranges, lettuce, tomatoes and watermelons. Russel wept at the color.

Women leaned with their elbows on pillows at their window sills, idly gazing at the street scene, or shouting at children in the street, or engaging in conversation with a next-door neighbor, window to window. Everything seemed to be going on at once; men hurried across streets pushing loaded racks of clothing, and boys carried bundles of cut cloth to be sewed at home for bosses, who sent out the cut pieces and later collected the finished garments. Sweatshops in every block hummed with their machines, and small industry crowded in among the workers in the neighborhoods where they lived.

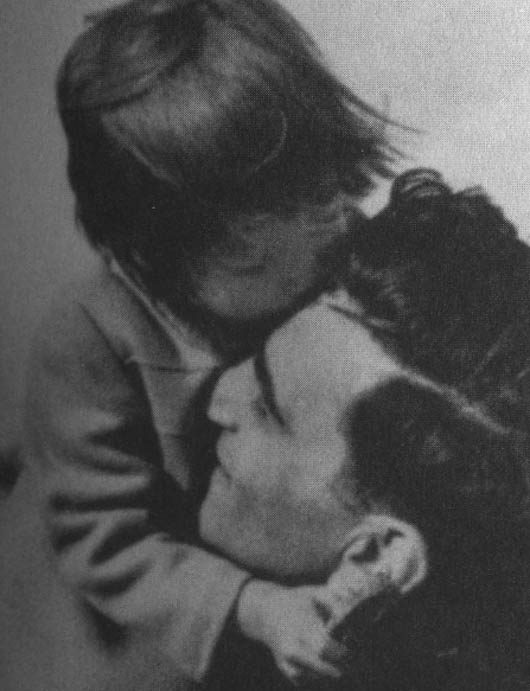

George with daughter Linda

George with daughter Linda

At Coney Island we went into the hall of mirrors and laughed at ourselves, then as we stepped out onto the promenade, a blast of air raised Mary's skirts above her head; her arms went up too, and she was a pretty Hower, a half-naked shrieking girl. We rode the giant Ferris Wheel which lifted us up above the city and the sea, and when our car reached the top, high above the surrounding city, a system of rails started the car in a slide of its own as the rest of the wheels stood still, and rocked us in a violent pendulum motion before it came to an abrupt stop. Russel bellowed, and we screamed. His voice rose above the noise of the holiday makers, "GET US OUT OF HERE!" The Ferris Wheel made a half revolution, without any stops, brought us to the platform and let us out.

We took Mary and Russel sailing on the Hudson before we laid our cat-boat up for the winter, and we found that our boat, so roomy for two during the previous summer, was crowded with four. On our return to the mooring, I lost my balance in excitement and misjudgment, and in what seemed to be slow-motion comedy I fell in a forward somersault into the water. I seemed to see myself fall, and I clambered out in chagrin.

There was no way to be adequately myself while, soaking wet in a new red sweater and skirt, I entered the hotel lobby and dripped up in the elevator to change clothes. Zukofsky went with us to strip our boat for laying her up at the end of summer.

the Oppen family

the Oppen family

I took off the sail and tied it into a bundle, Louis continuing to talk. I started up the steel stairway to Riverside Drive, with Louis right behind me; George followed with his burden, up the stairs, across the tracks, and up the next Hight of stairs. Louis gallantly protested, "Mary, let me carry it, Mary please." Near the top I turned and handed him the sail. He staggered and went down a few steps before he landed against the railing to recover himself. I gathered the bundle again in my arms and dragged it to the top of the stairs.

Aunt Elsie took me to lunch one day to ask me if we intended to have children. I thought it was none of her affair and said no, but I did not have any kind of birth control and we had gotten no advice from doctors we had asked. She took me to the birth control clinic the next day and I never had to have another abortion. I wrote to Nellie and to my sister-in-law Julia, who had so many children, and told them they must find birth control clinics at once. Nellie replied in high glee, with cartoons, but Julia could not arrange getting from Oregon wilderness to a San Francisco birth control clinic, and she had one more chnild. At that time there were only eleven states that allowed even doctors to give birth control information.

Mary

Mary

During those years Linda and I did not laugh much. In pictures we look like refugees — remote, thin and bleak. Linda looked like a little wild girl; she would not have her hair combed. When George came home at last I told him, "Linda does not understand what a joke is; laughter is threatening." George made little jokes for her, and we laughed, but we needed time to recover our spirits.

Linda also needed to learn that George and I were equal as her parents — she would turn to me for permission when George had already told her what she might do.

New York City was not a place we understood in ways we needed to understand to bring up a child. George and I visited the school I would have chosen for her to attend in the fall; we tried to imagine what life was like for a child growing up on city streets, and we quailed from it.

We needed to get out of New York City, where tension and too much argument had to be faced; we needed to get away from the scene of wartime living and be a family again. We needed to be free of close neighbors and be together, just three of us, free of the tight living of New York City. We needed space, sky enough to see the sweep of it, stars at night, forests, to have a garden and ride horses.

We retrieved an old open trailer from New Jersey. George parked it at the curb in front of our house in Sunnyside and began to build it into a camping trailer for our trip west — we were going to California. Our neighbors were incredulous, and fathers brought sons on Sunday to watch George at work on the little camp trailer, making a place to sleep, a little shelf for a stove and food, a hitch for the car to pull it. They said, "That trailer will never make it over the Rocky Mountains." At war's end these neighbors were buying their first automobiles and learning how to drive them.

In March 1946, we drove west. Linda stood behind the front seat and kept up a constant conversation, happy that she had us where she could touch us. We had barely started to be a family when the war came upon us, and Linda had had only stories of a father. Her love was for us, and to be with us was her life.

Mornings we drove until we found a roadside place open for breakfast. We discussed farms, animals, horses; I told Linda an endless story about Hoppy the Frog until she began calling me "Hoppy." We passed horses on the prairie, and George caught one for Linda; he has a poem:

"Horse," she said, whispering

By the roadside

With the cars passing.

Little girl welcomed,

Learning welcome.

In France in 1930, from the art of the Louvre, paintings speaking out of different times, from the streets of Paris which make their patterns and take their names from the earliest use the ancients gave them, from a cafe for writers, tourists, artists or students, we looked on and tried to absorb the meaning to us of a culture which accepted living artists, writers and students into the social fabric with a freedom we had searched for in the United States and had not found.

I think I travel to ask the questions which are hard to formulate about one's own times because one is in the midst, at home, of all that one has seen so often that one does not receive the jolt that might confront one with the uncomfortable but important question. Not with answers — answers are not possible for one's own times and in one's own place. The answer only becomes obvious after time has passed, and we can see, if we have survived it, the predicament that we have passed through.

Mary Oppen was an artist, photographer and poet. She was also the wife of George Oppen and this is an excerpt from her autobiography Meaning: A Life.

"Heart of a Girl" - The Killers (mp3)

"Carry Me Home" - The Killers (mp3)