POETRY

POETRY In Which Kenneth Patchen Created Us All In His Image

Monday, September 15, 2014 at 11:32AM

Monday, September 15, 2014 at 11:32AM

"Hiya Ken Babe, What's The Bad Word For Today?"

by JONATHAN WILLIAMS

They've never made a movie about Kenneth Patchen. Now they're too late. The only guy who could play him, Robert Mitchum has just died. He had the voice, the build and the sleepy eyes. He had the laconic barroom style to deliver a poem like "The State of the Nation" whose last line I have altered in the title above.

It's difficult to fathom why he's not read by the young these days. Do the young have enough grounding to read any unconventional poet these days? Basil Bunting always insisted there were still plenty of "unabashed" boys and girls about, but their slovenly teachers had never trained them in the literature that mattered. There were three or four decade when Kenneth Patchen was a poet who mattered to a lot of people. I was having lunch last autumn with J. Laughlin, Patchen's old friend and his publisher at New Directions. He shook his head sadly, "They just don't read Kenneth anymore - how can we understand that?" I don't think we can understand. Each century produces a Blake and a Whitman, a Ryder and a Bruckner. They didn't arrive out of the empyrean with fan clubs and web sites.

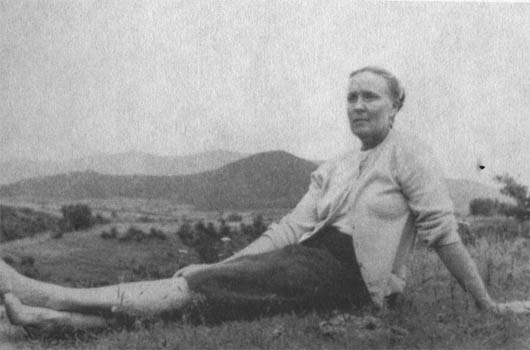

Patchen wrote at a time when most writers stayed home and wrote, in places like Rutherford, Old Lyme, Fort Atkinson and Sausalito. The previous generation was into celebrity and reporters followed them to Pamplona, the rue de Fleurus and Rapallo. Patchen had to stay home, and stay in bed - his wrecked back gave him no mercy. Except for a few sessions of poetry-and-jazz with Charles Mingus in New York in the late 1950s, and with the Chamber Jazz Sextet in California, Patchen was a private man, not on stage.

It is instructive, perhaps, to contrast this kind of life with that of two later poets who have recently died: Allen Ginsberg and James Dickey. Both of these men spent early years working public relations on Madison Avenue and neither stopped jabbering for a single second thereafter. Ginsberg was a mensh. His desire to be the spokesman of his generation was the last thing I could imagine or would want, but we always enjoyed being together on what were rare occasions in San Francisco, New York or here in Dentdale. He upset a lot of squares, he opened up liberating avenues, he put himself on the line; but, may I be excused if I have to say that most of the poetry struck me as hard-sell advertising. I was reminded more of Walter Winchell and Gabriel Heater and Paul Harvey than of the Buddha.

Sheriff Dickey, more bubba than mensh, was unbelievably competitive. At a poetry occasion in the White House put on by Rosalynn Carter and Joan Mondale, Jim barely had time to shake my hand. He whispered to his wife, "Come on, honey, we got to work the crowd." He never forgave me for writing to someone that Deliverance was about as accurate about goings-on in Rabun County, Georgia, as Rima the Bird-Girl was in Green Mansions, by W.H. Hudson. I also made the mistake of quoting Mr. Ginsberg on Deliverance: "What James Dickey doesn't realize is that being fucked in the ass isn't the worst thing that can happen to you in American life."

Compared to these public operators, Patchen was as remote as one of the Desert Fathers. (The Desert Fathers is not a rock group.)

I sat in Concourse K at O'Hare Airport in Chicago recently, reading The New York Times and Fanfare and watching the passing parade for about three hours. This is very sobering work. I am not sure I saw one individual who was dressed individually. Most people looked like mall-crawlers. Most people looked overactive and stressful. They were moving at speed, like ants in a formicary. Others were merely bland and moved like wizened adolescents. It would be future ti suggest any sign of appetite among these citizens for Kenneth Patchen or J.V. Cunningham or Wallace Stevens or James Laughlin. A few people waiting for the evening flight to Manchester were reading paperbacks purchased at the airport. John Grisham and Danielle Steele and Dean Koontz were most in evidence. (One young man was reading Camus, but we must pretend he doesn't exist.) I decided to buy The Door to December by Dean Koontz, "a number one New York Times author who currently has more than 100 million copies of his books in print."

Whatever the cause of his crumbling self-control, he was becoming undeniably more frantic by the moment.

Wexlers.

Manuello.

Why was he suddenly so frightened of them? He had never liked either of them, of course. They were originally vice officers, and word was that they had been among the most corrupt in that division, which was probably why Ross Mondale had arranged for them to transfer under his command in the East Valley; he wanted his right-hand men to be the type who would do what they were told, who wouldn't question any questionable orders, whose allegiance to him would be unshakable as long as he provided for them. Dan knew that they were Mondale's flunkies, opportunists with little or no respect for their work or for concepts like duty and public trust. But they were still cops...

That goes on for 510 pages. So, fellow-stylists, there is hope for us all, whether you like square hamburgers or round hamburgers. I go for the round ones, as I am sure Mr. Koontz does. McDonald's has sold over ninety billion of the little buggers. Here's to LitShit and a kilo of kudzu up the kazoo!

New York publishers calculate the fate of the American novel is in the hands of five thousand readers who will actually purchase new hardback fiction. At the Jargon Society we would by delighted to sell five hundred copies of the latest poetry by Simon Cutts or Thomas Meyer. It might take ten years. Of course, out there in the real world, thousands of verse- scribbling plonkers crank out a ceaseless barrage of what Donald Hall calls the McPoem.

Oracles in high places proclaim a Renaissance of Poetry. A distributor tells me of the purchase of twenty thousand hardback copies by a woman poet I have never read nor hear of. The hermits and caitiffs I hang out with don't explore other parts of the literary jungle, and just stick to their Lorine Niedecker and Basil Bunting, and even drag out volumes of Kenneth Patchen when the fit is on them. We few, we (occasionally) happy few...

How did we odd readers find our way to Kenneth Patchen? He, of course, would never have been in the curriculum at St. Albans School or at Princeton, my adolescent stomping grounds. I stumbled across a pamphlet by Henry Miller, Patchen: Man of Anger & Light. Miller I knew about because evil Time magazine had so vilified his book The Air Conditioned Nightmare that I took the next bus to Dupont Circle in Washington D.C. and bought it at the excellent bookshop run by Franz Bder. By the time I was ten I had the knack of discovering the books important to me beyond those required at school. But I was lucky. I had three good teachers in prep school and I lived in a city with real bookstores. And reading books was something you did. Nowadays, books are a form of retro-delivery system with no cord to plug in. Way uncool.

How did we odd readers find our way to Kenneth Patchen? He, of course, would never have been in the curriculum at St. Albans School or at Princeton, my adolescent stomping grounds. I stumbled across a pamphlet by Henry Miller, Patchen: Man of Anger & Light. Miller I knew about because evil Time magazine had so vilified his book The Air Conditioned Nightmare that I took the next bus to Dupont Circle in Washington D.C. and bought it at the excellent bookshop run by Franz Bder. By the time I was ten I had the knack of discovering the books important to me beyond those required at school. But I was lucky. I had three good teachers in prep school and I lived in a city with real bookstores. And reading books was something you did. Nowadays, books are a form of retro-delivery system with no cord to plug in. Way uncool.

By the time I was twenty and had dropped out of Princeton to study painting and printmaking and graphic design, I was into Patchen in a big away. I read him along with Whitman, Poe, H.P. Lovecraft, Williams, e.e. cummings, Edith Sitwell, Robinson Jeffers, Hart Crane, Kenneth Rexroth, Thoreau, Randolph Bourne, Kropotkin, Emma Goldman, Henry Miller and Paul Goodman. Before I was twenty-five I owned the manuscripts of The Journal of Albion Moonlight and Sleepers Awake. I had over forty of Patchen's painted books and a few watercolors. I'd published KP's Fables & Other Little Tales during my stay in the medical corps in Germany. What was the attraction?

Patchen was an original. Someone said, equally, of Babe Ruth: "It's like he came down from out of a tree." He was ready to play. Patchen and the Babe were heavy hitters, and nobody struck out more.

There is a towering pile of Patchen poems that amounts to not much. But he really does have twenty or twenty-five poems that seem as good as anybody's. He had power, humor, intuitive vision and a kind of primitive nobility. He knew his Blake and Rilke. He loves George Lewis' clarinet and Bunk Johnson's comet. He drew fabulous animals and painted very well. There was nobody like him.

Oh nobody’s a long time

Nowhere’s a big pocket

To put little

Pieces of nice things that

Have never really happened

To anyone except

Those people who were lucky enough

Not to get born

Oh lonesome’s a bad place

To get crowded into

With only

Yourself riding back and forth

On

A blind white horse

Along an empty road meeting

All your

Pals face to face

Oh nobody’s a long long time

The poet, painter and publisher Jonathan Williams died in 2008.

"I've Waited For So Long" - The Juan MacLean (mp3)

"The Sun Will Never Set On Our Love" - The Juan MacLean (mp3)