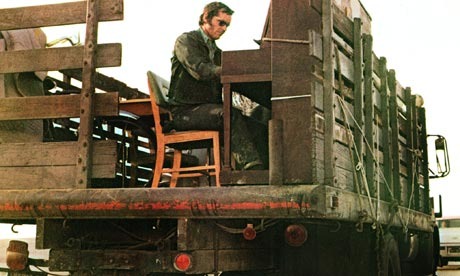

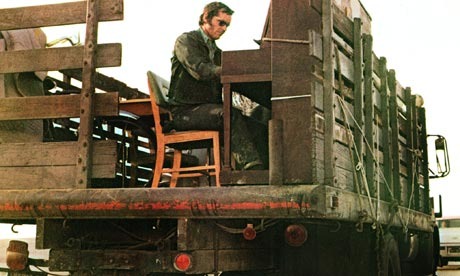

Playing Piano On Top Of A Truck In Traffic

by MOLLY LAMBERT

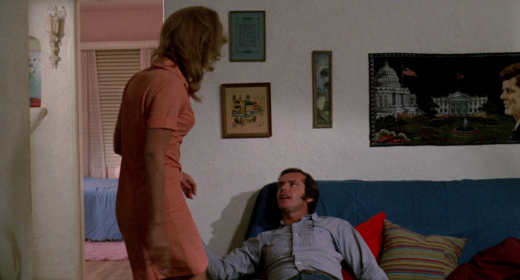

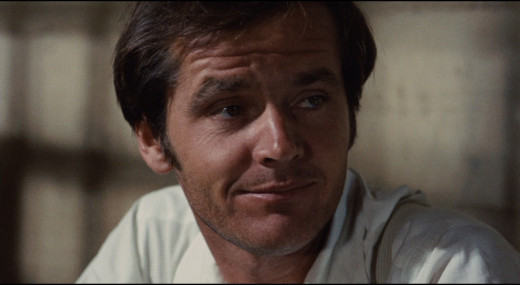

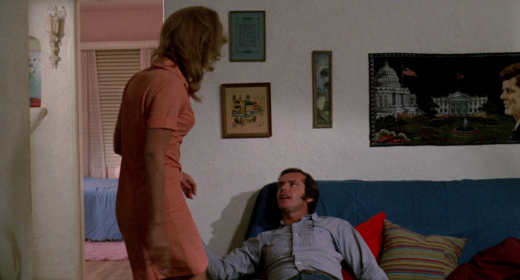

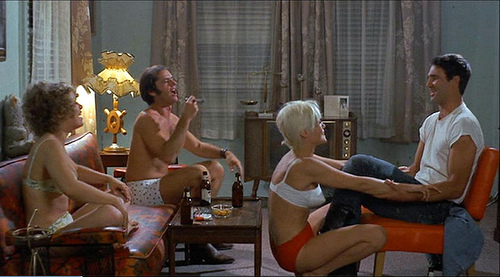

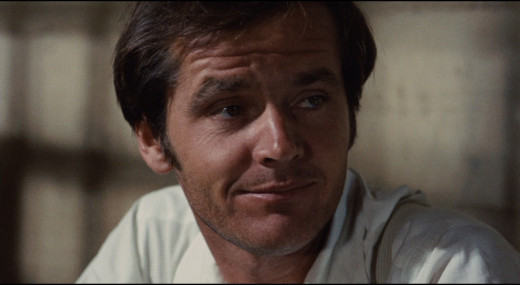

Five Easy Pieces, 1970

dir. Bob Rafelson

MOLLY LAMBERT V. JACK NICHOLSON: ROUND 2

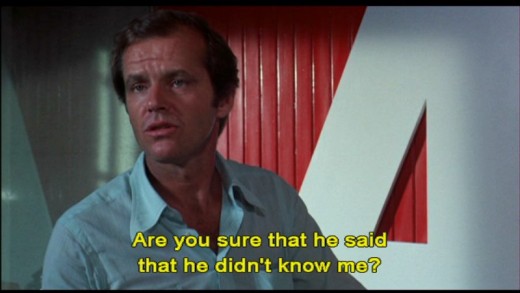

I encountered Jack Nicholson onscreen for the first time in 1997, when I saw James L. Brooks' As Good As It Gets. In that film Jack Nicholson plays a character whose entire existence requires the context of "Jack Nicholson" to make any sense. Here is how I saw it: a sad neurotic old man totally undeserving of love gets his wish fulfillment fantasy via a much younger waitress who doesn't really make any sense as a character and Greg Kinnear is gay. I had never been so mystified to see a movie win so many awards. "Man, Hollywood..." I said, shaking my head perplexedly and being fourteen.

I enjoy an intellectual romantic comedy as much as the next English major but I could not get behind that movie. We're all trying for Annie Hall but there's nothing worse than characters that assume your sympathy without really earning it. Woody's heroes are often horrible people but they manage to be sympathetic. Woody's worst movies have many of the same problems as As Good As It Gets. "You make me want to be a better man." What made you so sure you're such a bad man to begin with Jack?

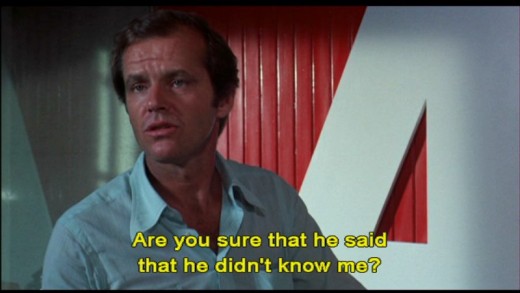

My freshman year of college I saw Carnal Knowledge, a movie which opens (semi-hilariously) with Jack Nicholson as a freshman in college. Suddenly I got Jack Nicholson. I got what As Good As It Gets had assumed I would already know. And I understood that the current Jack Nicholson, the grandfatherly type in sunglasses in the front row of the Oscars, still felt exactly the same inside as this guy I really wanted to fuck. And that was really weird, vaguely creepy, confusing, hot, and the very end of puberty.

1970s Jack Nicholson is THE man. He wins everyone over and gives the appearance of not trying. He walks into the room and pushes the needle off the record player. He looks incredible in clothes. He says something completely terrible and insulting and then is forgiven because he smiles to acknowledge that he knows he is being terrible. What he wants he just takes and if he can't get it he destroys property. He is charming but he is also evil. Are all charming people evil? Isn't that sort of what charm is about?

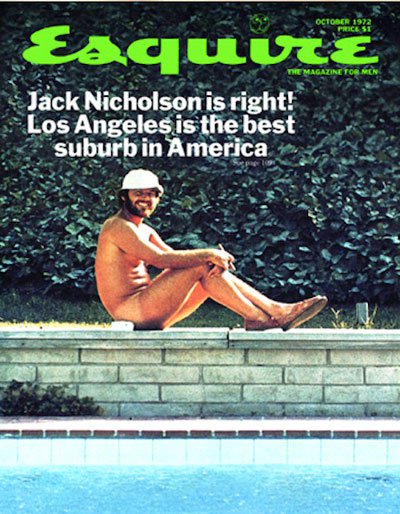

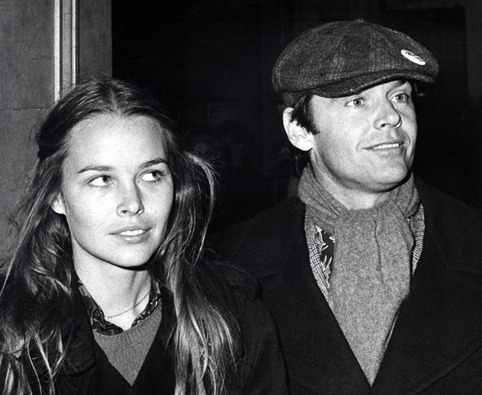

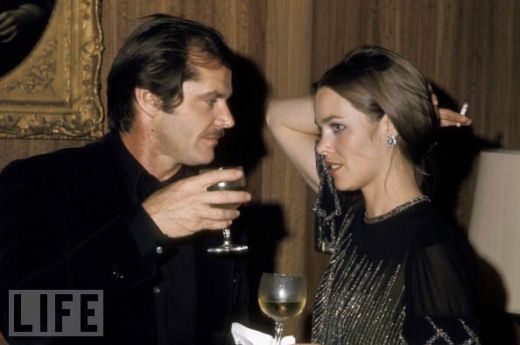

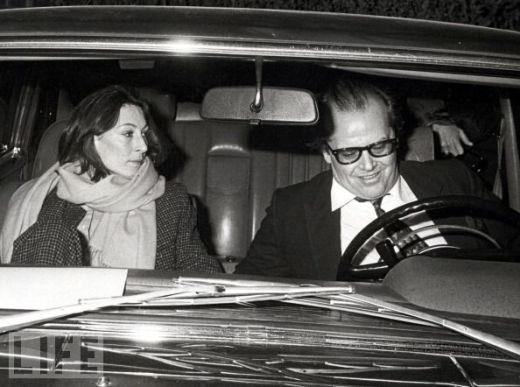

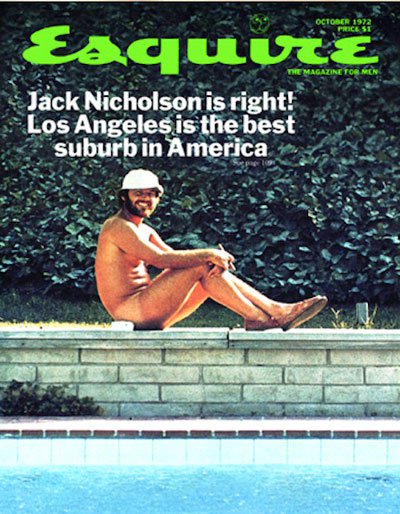

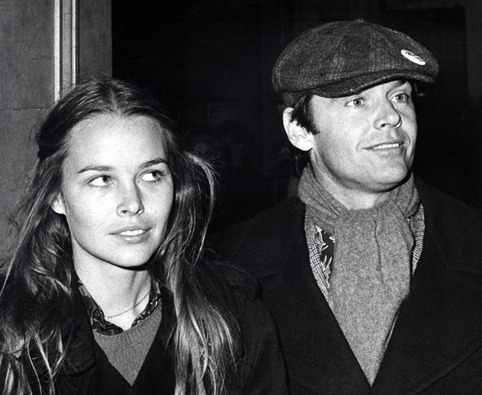

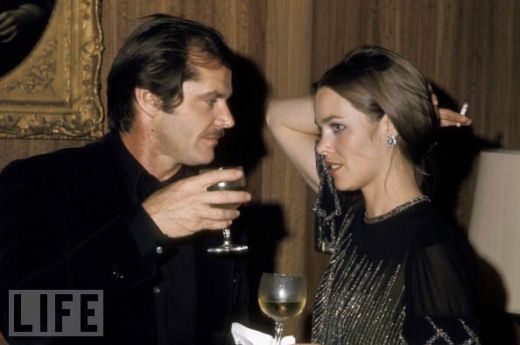

image probably repeated on This Recording the most times in different posts

Jack Nicholson believes that men are innately different from women ("cunt...can't understand normal thinking") He thinks men have egos that overpower everything around them and appetites that require constant maintenance to be restrained. He does not understand that this is the human condition. It would be insulting to say that he is too old to learn this, but I suspect it is something he has secretly known all along, and that most of being Jack Nicholson is pretending to be "Jack Nicholson" for the enjoyment of people wishing to live vicariously through his imagined lifestyle.

That men have a brute sexuality uncomplicated by emotion is the biggest lie ever. So why is it pushed on us so hard, in Jack, James Bond and Jay-Z? It is the founding lie of rap music and pornography. Remember how cool Jay-Z used to be and how lame he is now that he's crazy in love with Beyoncé? Why did he seem so much cooler when he was pretending like no woman ever had any effect on him? Because the truth; that men are vulnerable, with emotional needs, things projected on people like Jennifer Aniston (who is fine, duh) is so deeply threatening to the present order of the universe.

The men who admit to these vulnerabilities are free. To quote myself to myself: It's not emasculating if you like it. The other human condition is being deeply horribly sensitive in a way you are convinced must be specific to you. We are all the main protagonist of our own life. That is why Jack Nicholson is so beloved. He is bigger than everyone else onscreen. I don't think everyone who has a good live show hates themselves necessarily, but that is certainly the message suggested by Five Easy Pieces. Plenty of people just hate themselves and don't even have a good live show.

There's an early scene where two girls hitting on Jack start talking about his hair and he looks tremendously worried all of a sudden, like they might start talking about how he is balding. That men have no physical insecurities is the other biggest lie ever. Vince Vaughn might not have any physical insecurities but damn dude you fell off SO HARD. In Husbands Cassavetes is constantly bringing up his own shortness. Can a woman have a Napoleon complex? I'd still like to be tall every time I'm at a show.

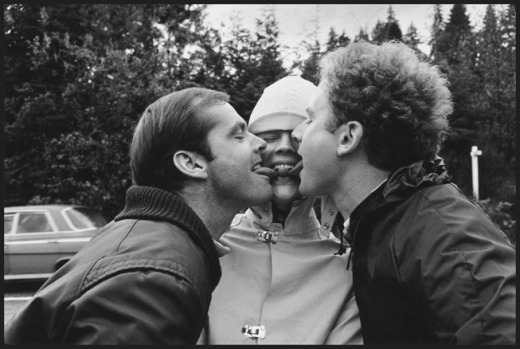

"Hey Dennis. Hey Dennis. Hey Dennis, man. Hey Dennis. I'm going to fuck your wife."

And yet young Jack Nicholson is as attractive as a person could possibly be, in part because he pretends not to care. Is it pretending not to care that is attractive? Actually never caring about anything is completely impossible. We all care in some situations and feel nothing in others. And then pretend to care/not care in various amounts. Thus is Don Draper. Bill Murray's whole pathos is perched on the gulf between them.

We associate sunglasses with cool, and Jack Nicholson with sunglasses. Sunglasses block the eyes from view, thus blocking others from being able to see what emotions a person is actually feeling. They do not prevent you from still feeling those emotions. A character like Jack Nicholson's Bobby in Five Easy Pieces, who so aggressively displays his ability to hurt people and not ever feel bad about it, is more terrified of getting hurt than anything. Hurting other people first is merely a preemptive strike.

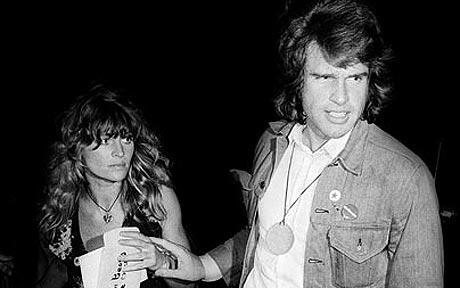

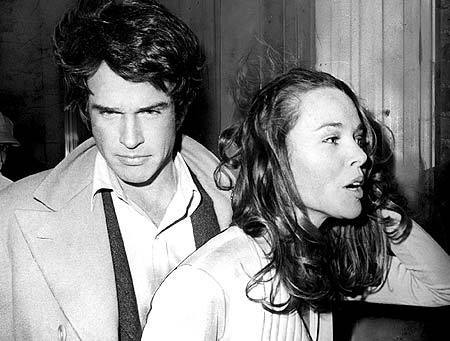

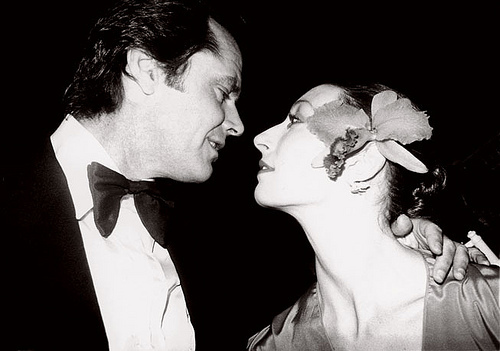

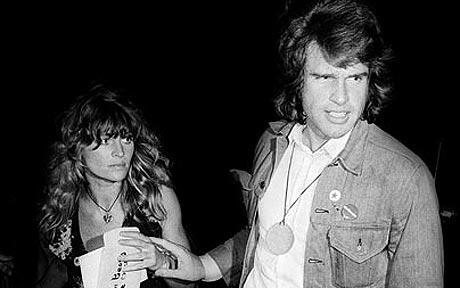

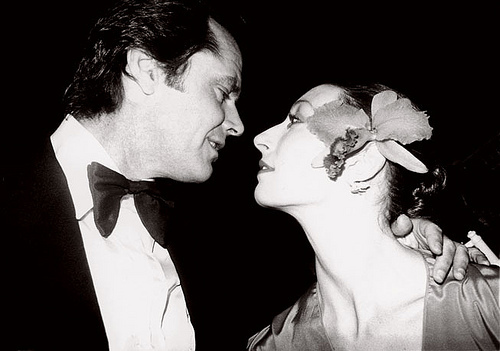

Value is largely construct. Competition creates value. I guarantee you Warren Beatty never once left Julie Christie alone with Jack Nicholson. The reason Warren would never have left Julie Christie with Jack Nicholson is because he knows just how easily he Warren Beatty, the great seducer, was seduced by Jack. The weird thing about straight male sexual competition is how little it can have to do with women. That's why it is so refreshing when men treat you like a human being. That it is refreshing is depressing.

Discussing the Warren Beatty/Jack Nicholson/Dustin Hoffman FMK post Julie Klausner and Natasha Vargas-Cooper wrote for The Hairpin (a truly astonishing piece of writing that is, to quote James L. Brooks on Annie Hall, "like watching a spaceship land") in an e-mail with me Klausner said "Well, the '60s caused the '70s. And in some cases, the '70s caused the '70s. These three bros basically caused the women's movement."

It is not hard to feel totally horrified reading the infamous Teri Garr AV Club interview where she talks about how Dustin Hoffman grabbed her ass in every take of a scene on Tootsie and Sydney Pollack thought it was hilarious. I get the impression this is why Megan Fox actually left Transformers. I want to radicalize Megan Fox so fucking bad. I am sure she has caught on by now that it is still always Mad Men somewhere.

Five Easy Pieces alternately celebrates and repudiates Jack Nicholson's brand of charisma. It is Easy Rider's black swan for sure. It understands that volatility is not without expense, but neither is it without enormous payoffs. Nicholson's character Bobby is not violent, but he uses speech as violently as The Shining's door axe chop. Talking is a sexual act and Jack Nicholson is always trying to fuck everything in sight.

The problem with being a woman and romanticizing a boys' club is that you would not actually be welcome. The fantasy of being welcome there is an impossible fantasy, one nobly attempted by Anjelica Huston. You never feel completely welcome, because your presence makes it into something else. Not all groups of men are boys' clubs. Boys' clubs specifically involve the exclusion of women with the occasional tokenism.

Five Easy Pieces is a slice of life movie. Much of the tension comes from putting characters in rooms together and then leaving the audience in suspense a little bit about what their relationship is to one another. You think Bobby is a blue collar drifter and then it turns out he's an upper class kid trying to escape his intellectual family. It's very beautiful and realist (László Kovács!), evoking Ed Ruscha in the oil fields portion and the figurative work of Fairfield Porter in the last act at the family estate.

The famous "chicken salad sandwich" scene, where Jack as Bobby (but let's face it, Jack) berates a waitress is about the way you put yourself on stage sometimes in order to perform your personality. Involuntary non-genuine performance (as in working retail) is different from voluntary genuine performance. Whether genuine performance is a contradiction is an ultimate question. I had just been talking with Tess about how we both often insist on ordering for everybody at restaurants. What the hell is that about?

Performing yourself all the time is exhausting. That's why traveling with people is so hard. There's no person that doesn't need downtime from being themselves. The public self is such a weird thing, especially for women. Kartina Richardson wrote a great essay about Black Swan and bathrooms, bathrooms being one of the only places you can escape the gaze of others (also the only thing I remember about The Bell Jar).

Jack Nicholson can be a truly astonishing actor. He may be arrogant bordering on sociopathic, but he earned it with his performances. Towards the end of Five Easy Pieces there's a moment where he stops at a gas station bathroom, looks at himself in the mirror, and you can see him think "Who the fuck are you kidding?" The most performative actor when he speaks, Jack does subtle remarkable work with silences.

He illuminates the intimate connection between the two; performing one's self, which you attempt to control and through that control other people, and then just being one's self, which nobody can control. That's what makes him so magnetic as an actor. He is never just a dick. If he were really just a dick, he would not be nearly as interesting. Jack, it is implied, is only such a dick because he is so deeply emotional. Endlessly relentlessly unable to stop feeling things, always trying to silence his inner self. It is what makes his performance in Chinatown so insanely perfect and poignant.

In Five Easy Pieces Jack Nicholson expounds so much forceful energy creating and implementing his persona, and then is disgusted by anyone who can't immediately see through it to his white hot core of self-loathing. He can't respect anybody who'd respect him. Does Jack Nicholson actually hate himself? His films are constantly positing this as a corrective to his real life image and insane seeming levels of narcissism but it could just be wishful justification for him fucking Paz De La Huerta.

Lest you think only men can be Jack Nicholsons, I give you Paz De La Huerta and Angelina Jolie. All eight hundred kids aside, I'm not sure Angelina Jolie is capable of putting anyone before herself any more than Jack is. When you take Ayn Rand as gospel certainly you can achieve some ambitious goals, but other more mundane ones become impossible. Compromise is seen as weakness, and human relationships require compromise. You can't really love anyone without giving up some control.

Taylor Swift's insane crusade for true love is just as impossible and entitled as Jack Nicholson's endless fuckquest. What is so super hilarious about Taylor Swift and her surprise face is that no amount of fake humility can cover up her tremendous ego, her enormous feelings of entitlement, and barely-disguised Kenny Powers rage that she has not been immediately given everything she feels she justly deserves. She won't own up to her aggression. She is a Jack Nicholson who is a virgin who can't drive.

Swift's experience with Taylor Lautner seemed to open her up somewhat to realizing that this thing she thought she wanted more than anything might not actually be what she wants at all. That there is a certain perverse pleasure in wanting and getting not necessarily present in having. That she desires John Mayer because she can't have him and doesn't care about Lautner until he is unavailable. That on a sick level she wants it to be hard, correlates difficulty to satisfaction, and like Jack is making everything impossible for herself. Hopefully she figures out next that she's primarily just horny.

Warren Beatty fell in love onscreen a hundred times before he ever fell in love. It's like the gap between John Mayer's music and John Mayer. If Jack Nicholson tells us in films and interviews that he is sensitive, that what he really desires is to be dominated by a woman with a personality as strong as his, does it matter if he's really still out fucking twenty year old cocktail waitresses? I am sure nobody finds the idea that getting laid by a new girl constantly is supposed to be making him happy more ironic than Jack.

How much of charisma is related to being a prick? I've always respected aggression much more than passivity. We all want to ask for things and be given them. At what point does aggression become poisonous? To what extent does its poisonousness aid in its effectiveness? Kanye, Brando, Tony Soprano, Tony Montana, Frank Sinatra, Don Draper, Kenny Powers, Kobe, LeBron, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, Daniel Plainview.

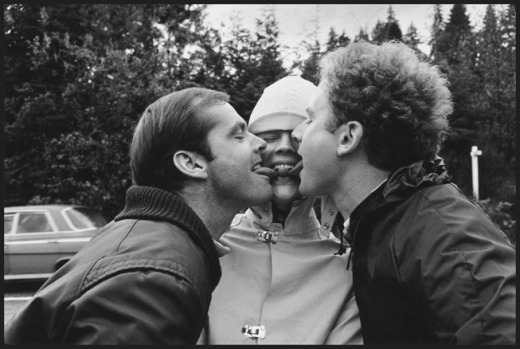

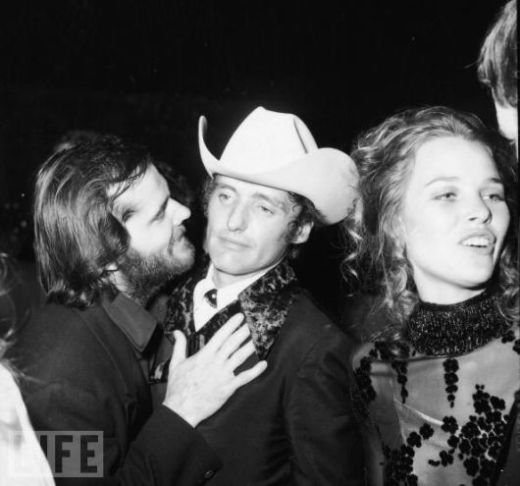

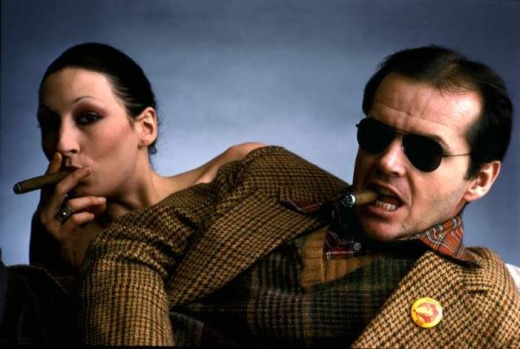

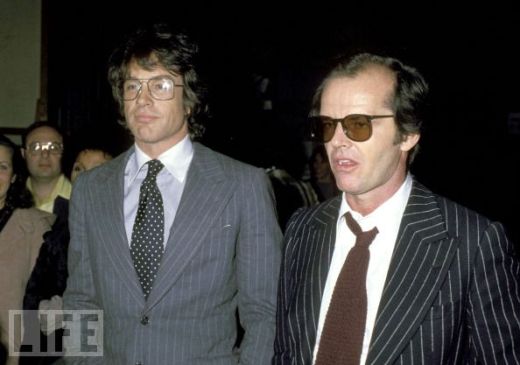

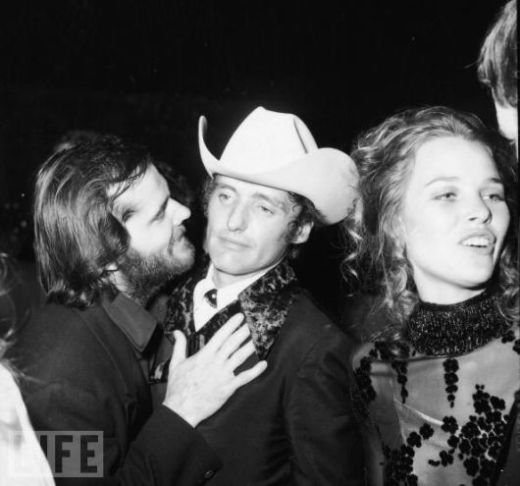

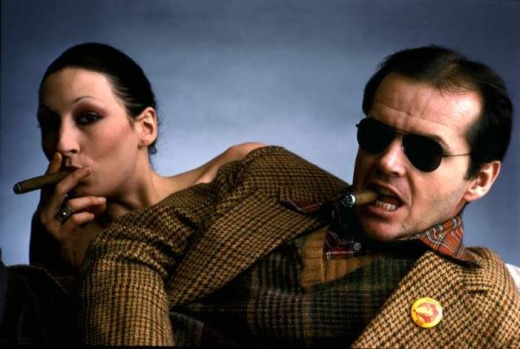

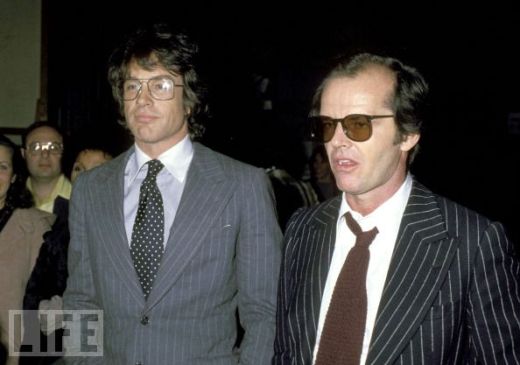

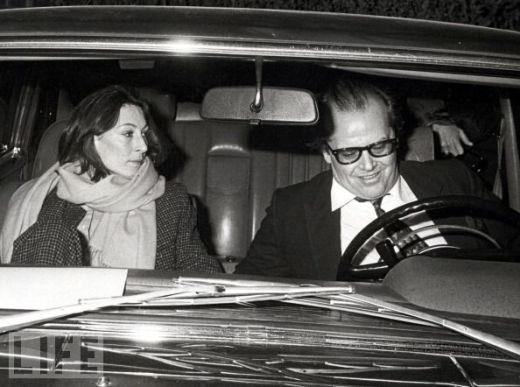

this doesn't need a fucking caption why are you even reading just look at these two

The man with no self-restraint is the American archetype. But he is always just kidding himself that he has no capacity for self-restraint. He restrains himself every day, even if it is mostly to restrain himself from restraining himself. There is wildness in restraint. People like having their bluffs called just as much as they like bluffing. They can't believe everyone buys what they're selling and they secretly hope someone won't.

That is also why I talk about John Mayer so much. If he brought any of the aggression that he brings to his own life to his music, he'd be making early Elvis Costello albums. Although to be fair, those early (perfect) Elvis Costello albums are about my least favorite kind of prick, the person who is a vengeful angry prick about how he's not getting laid, which is really the same kind of prick Taylor Swift is. Ladies is pricks too.

Everyone is chasing the feeling of winning. The feeling of triumph. And yet while short term success does bring temporary happiness, endlessly chasing ephemeral successes is a guaranteed roadblock to long-term happiness. And then sometimes long-term happiness can get really fucking boring and you remember what you liked in the first place about the whole process of chasing it. No person can always be winning at all times. Into each life a little The Two Jakes/Anger Management/The Fortune must fall.

I also watched Nicholson's directorial debut Drive He Said, which has some genuinely astonishing shots and sequences. One wonders why Nicholson didn't direct more, although the failure of The Two Jakes probably accounts for that (Jack had no chance at topping Polanski). Drive He Said is not a film noir but a coming of age movie about a college basketball player. Nicholson never appears in it, but his aura is spread out among the three main characters. I was never bored and I was occasionally stunned.

The protagonist (William Tepper) is a troubled athlete, possibly more conventionally handsome than Jack but lacking any of his magnetism. The guy utterly looks the part but there is nothing there, no spark. Whatever Jack Nicholson has, this guy doesn't have it, which brings us back to what it is exactly that Jack Nicholson has. Michael Margotta plays the crazy radical roommate like James Franco in Pineapple Express.

Nicholson's deep understanding of cinematic aesthetics makes itself evident immediately. Hidden safely offscreen he elucidates some of his own private themes; the conflict between the athletic physical self and the intellectual spiritual self. Jack exposes the pure graceful masculine performance of basketball as the inspiration for his own acting style and generally proves that he is a sentimental Irish-Catholic boy.

The best and most revelatory performance belongs to Karen Black, who plays Nicholson's conception of a sort of female Jack Nicholson. It is a testament to Karen Black's acting talents that I had no idea she was not really her character in Five Easy Pieces, who is kind of a beautiful idiot. In Drive He Said she plays a female character that is so much more interesting and complex than most of what you see onscreen that it makes you a little depressed there aren't more movies with characters like this.

It's incredible that Jack Nicholson manages to do what seems to elude so many male directors; he gives his female character subjectivity. Karen Black's Olive is judged no more or less harshly than the men. She is naked several times but never merely objectified, which is amazing given Karen Black's cartoonish beauty. She is neither overly idealized nor overly cruel. She is idealized and sentimentalized by the main character but not by the film. Jack Nicholson is not a misogynist. He's a champion of pleasure. He doesn't hate women at all. He loves women. He loves them too much.

Sometimes when I go in really hard on somebody I can't tell if it's obvious that I'm only going in that hard because I respect them a lot. I went in incredibly hard on Aaron Sorkin because I loved The Social Network. You know what's cooler than being quoted a million times? (yes, you do) Some things you love unconflictedly, but I'm always most drawn to the things that open up internal contradictions. It's not just that I enjoy Jack Nicholson's acting and want to fuck him but that I feel exactly like him constantly.

I'm writing about him again because of all those contradictions; that me feeling like Jack in no way means that Jack ever thinks he feels like me (the mistake Madonna made when she took on Warren Beatty), that it can be really fun to watch somebody being a prick until they're being one to you, that channelling ability sometimes means having to crush everyone in your path and there's really no way to be nice about it.

That women, starting from birth, are encouraged and expected to be "nice" in ways that men are not, and then are rewarded and punished accordingly throughout their lives. How an old man can live on eternally in the memories of the extremity of his talents as a younger man. I will probably keep writing about Jack Nicholson forever. At least as long as we're still stuck in traffic and I've got this piano on top of this truck.

Molly Lambert is the managing editor of This Recording. She is a writer living in Los Angeles. She twitters here and tumbls here, and runs GIF Party and JPG Club. She last wrote in these pages about author photos.

"In the Real World" - Bright Eyes (mp3)

"Singularity" - Bright Eyes (mp3)

"Lua" - Bright Eyes (mp3)

MUSIC

MUSIC  Friday, August 12, 2011 at 9:00AM

Friday, August 12, 2011 at 9:00AM

beach jogging w/ sean penn

beach jogging w/ sean penn

her first nude portfolio

her first nude portfolio

dancing with 13 year old chris finch on a british tour

dancing with 13 year old chris finch on a british tour her wedding to penn"Borderline" - The Flaming Lips (mp3)

her wedding to penn"Borderline" - The Flaming Lips (mp3)