THE WORLD

THE WORLD In Which The Dandelion Clock Strikes Midnight

Monday, January 19, 2015 at 10:30AM

Monday, January 19, 2015 at 10:30AM

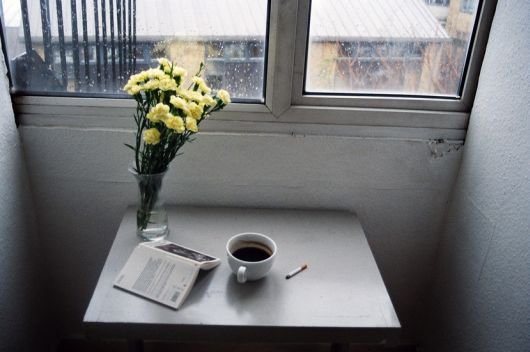

Bouquet

by HEATHER MCROBIE

Running alongside the events of those years was like in the cartoons where the animated out-sized character doesn’t realize he’s run off the edge of a cliff, until he looks down and so – to comic, cartoonish effect – suddenly starts falling.

Sometimes I thought of Tahrir Square like a coral reef, everyone moving as one, shoals darting between the barnacled city walls. Sometimes I thought of breezy, light Tunisia like a dandelion clock that all the young people and sad people blew at once, scattering the seeds of it everywhere, like this would be the first and last birthday cake whose candles we’d all ever get to blow out. At other times I thought of it like a grapevine, each bunch ripening in tandem, and at other times I couldn’t believe any of it at all. A lot of metaphors also ripened during this time and because we were still growing up we overused all of them, and I’m sorry for that. There are lots of stupid, easy things to say about spring.

The man I was in love with then did algebra and never used a metaphor, which I respect now more than I did when things were starting. For the purpose of this story I’ll use his brother’s name, Ibrahim, not so much for anonymity but more just because things between us were always a bit dislocated like that, like someone forgot to carry the one in an equation. Something always got left over from the last thing, or nudged down one unit in a row.

He wasn’t Brahim, my friend from early Cairo-unbelievableness, with whom, in the infinite possibilities of this outside-time year-zero, I carved out a perfect friendship uncorroded by the complications of politics and sex. “Guess how short my skirts are when I go out in London? And guess how short they are when I go out in Manchester? And guess how short my skirts are when I go out in Liverpool?” Brahim would put his hands to his face like two giant leaves covering the centre of a sunflower but you could tell from the glow that peaked out that he was always laughing. We were laughing in our language classes and laughing on the balcony and only not-laughing when he took me to the cemetery and even then afterwards he made jokes, of a kind.

The man I was in love with who studied physics and was bemused by all of this came with me on a boat to Tunis where we imagined all the ancient Greek shipwrecks that must lie between his port-city home and the port-city someone with his surname had once left for the lower-lip of southern France. We became professionally annoying with our photographs: every flag and every protest, me taking my dress off in our bedroom in the heat (later after Ibrahim left I was working at home in my underwear because it was too hot and heard the clicking of a camera by an amateur creep who was peering in through the window). We photographed the hospital and photographed the morgue and photographed the bars called “Facebook” and the cafes called “Twitter”. I sent emails to professors in Europe and North America telling them all their theories were outdated now, after this miraculous blossoming of spring. I mainly got out-of-office replies.

Since Ibrahim grew up in the south of France but studied in Paris I came to understand a relationship that had nothing to do with me, a north-south tension that didn’t play out in my life. The ‘grandes ecoles’ of regimented Napoleonic education and the starched northernnesses of his classmates were as alien to him as they were to me, and he moved around Paris as half-bemused as he was half-bemused in Tunisia, home of his father. I thought of him – because I loved him and he loved mathematics – as the mathematically-precise centre-point between these two, Paris and Tunis, held comfortably in his smiling certainty that this would all turn out alright, don’t worry my love. I started to think of the Mediterranean like a mouth, with southern Europe as the upper teeth and north Africa as the lower teeth, how they had once slotted together, before some tectonic shift exposed the wet middle of sunken Greek ships.

Years later in Odessa I thought similarly and differently of the Black Sea: Ukraine glistening above and Turkey propping it up assuredly from underneath. The heartening enclosed-ness of it all. I liked to hold on to enclosed things, after the places and events since the start of the revolution that unraveled and just kept on unraveling. I thought maybe the Mediterranean Sea was Ibrahim’s mouth beaming in the sun and the Black Sea was Amela’s mouth in that period when I thought about Amela’s mouth all the time, when she’d sit out by the library, and say funny and clever things and purse her lips in between so that they looked, improbably, like an exact map of Australia coloured in with lipstick. ‘Amela’ is also a fake name for someone whose identity I need to smudge into imprecision, but her lips really did shape themselves, perfectly, just like that.

The best and worst thing about growing up motherless is you have to learn the artifice of femininity really carefully, like you’re learning algebra – when to carry, when to drop, when to press a little, when to stop. I remember thinking of this in the Tunis hospital where the blue corridors were casually lined with dirty bandages. How the hands of the nurses wafted at me in unison like seaweed in some sticky, maternal mauling. How had they learned to touch bodies like that? It seemed as definite as maths but whole in natural-ness, precise but organic, like a starfish. They sent me back to the apartment in Tunis with my own bouquet of bandages.

Ibrahim grew up in a town in France that had the same position as the town I grew up in in England: unromantically run-down, un-special, near to a famous port-city. Walking around it in the spring before the hospital I remember thinking how at least the Runcorn of France had palm-trees, and there was something to be said for what sun can to do wash away any kind of ugliness.

Much later I stood in a central station looking up the bus schedule to Tripoli and I realised that my period was late because I was looking at schedules; later I was looking at the bandages that lined the blue corridors of the hospital and realised we were all too late. But I couldn’t tell anyone because the doctor was so kindly and quietly explaining to me that it wasn’t meningitis, I was probably just overcome by events. Everyone was overcome by events.

Three years after the revolution in Egypt, Bassem Sabry, the brightest, truest young writer of those times, fell to his death from a Cairo balcony and I couldn’t stop thinking of him. I re-read his recent writing, shocked that he had touched something now as complete and grown-up as death. I couldn’t stop thinking of him and of how everything just tumbled like that. As the revolutions buckled under themselves everything was either the swollen pregnant pauses of the curfew or the sudden internal caving-in of blood.

All I want to remember from these years of my life is that night when he and I were taking pictures of each other in the dark. This was in Tunis before the hospital visit and before I found out that I needed glasses and I didn’t know how the pictures or anything else would turn out. I thought that it was going to be something blossoming and abundant – like spring, or a revolution. Instead of what it really was: something mutant and unsustainable – like a miscarriage, or a lie.

Heather McRobie is the senior contributor to This Recording. She is a writer living in Oxford. She has written for the Guardian, the New Statesman, Al Jazeera, Foreign Policy, the Times Literary Supplement and Salon. You can find her website here.

Photographs by Sumeja Tulic.