BOOKS

BOOKS In Which We Eat Pot Brownies With Tao Lin

Friday, July 12, 2013 at 9:47AM

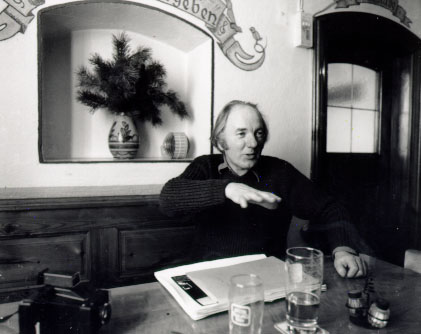

Friday, July 12, 2013 at 9:47AM  photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

Self vs. Author

Tao Lin stays awake in his apartment 2-3 days at a time, taking small walks outside to buy expensive vegan snacks while high on Adderall and Xanax. When I visited him at his studio apartment in Kips Bay, I liked the feeling that everything inside his space was there because it had once been brought in by someone else, for an unknown purpose (a kiddie pool, overturned in the kitchen – a kite, broken in a pile on the floor) not because it had passed a test before being admitted. I liked the feeling that nothing had been scrutinized after it was used, then rendered useless and thrown away. I liked the feeling that Tao did not give a shit about the mess. Or about how anyone perceived life inside his house.

I have a secret sympathy for the misanthrope. I get the hoarder. I understand the mad desire to hold on to every piece of accumulated material, to stay alone all day in a cool, dark apartment among one’s things. So I have always had benign feelings of admiration for writers like Tao Lin. I recognize the safety of indoors, and the fear of losing something precious simply because one deigned to enter the world beyond social media.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

When I first introduced myself to Tao Lin, I was 21 years old and still using Hotmail. I’d read one of his stories and e-mailed him to tell him I liked it. “I don’t have many friends,” he had said. “I don’t like being around more than one person at a time, usually. Or I don’t like people that much generally. I don’t know.”

For six years I “got to know” Tao through the internet, through emails and gchats, and then a week ago, I went over to meet him. He asked me to come around 4 p.m., a little after he woke up. When I arrived the door was propped open and he was sitting at a rectangular desk in the small studio. There were no lights on, except for the gooseneck lamp clamped to the mirror in the bathroom, emitting an eerie reddish glow on the doorway, and the melting shadow of sunlight coming in through the apartment’s only window.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

The room was crammed with broken things: lamps, piles of hangers, old clothes, huge blankets, and what looked like a collapsed tent. “That was from my ex girlfriend,” he said, in the kind of hushed, uncertain staccato that is his voice. Piles of dishes, unfinished art projects, scissors, tape, and envelopes, black plastic bags filled with who knows what, barricaded his desk and the surfaces around it. There was the distinctive sound of water dripping as I took a seat on a cluttered sofa and offered him a Tecate from my bag. I didn’t know what made everything so uncomfortable. He said “there’s beer,” and opened the refrigerator and took out a Wolaver’s.

Perhaps even more apparent than the commanding aura of hoarder tendencies in the place was a sense of absence - the apartment’s evocation of all that had been excluded, had failed to capture Tao’s interest enough to be brought in in the first place, which are probably most of the things of “good taste” or the things we see in stores and in one another’s houses. Tao’s apartment was not “comfortable” by any conventional means, but there was something comforting about an environment from which “disorderly actuality” had not been removed. I was pleased by the success of my plan. I felt that being inside of Tao’s apartment allowed me to understand him better.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

“What did you think of my book?” Tao asked, after we had been sitting there holding our beers for ten minutes. “Most of the reviews were negative.” I asked him about the fish on the wall, cut out of newspaper, and the broken lightbulb next to the Natalie Imbruglia CD on his desk. “My ex girlfriend gave that to me.” He stood up and went over to the tiny refrigerator and pulled out a rectangle covered in aluminum foil. “Someone sent these to me,” he said, and started breaking up small pieces of pot brownies, holding the freezer door open with his elbow. I took two 1x1 pieces and chewed them around and washed them down with Tecate. The conversation moved on, and I did not say I had tried to read the book twice but couldn’t finish either time.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

“Do you think memoir is more authentic than fiction?” I asked.

“No. I mostly just think in memoir that person is lying.” We sat together on the couch and signed in to Twitter.

“Don’t you think,” I asked, “men tend to write fiction instead of memoir when they want to write about themselves, because of ego?” “No,” he said.

“Really,” I said. “Why do men hardly ever write memoir?”

“I don’t know,” he said.

“Why don’t you write memoir?”

Under my twitter handle, Tao typed in the appropriate amount of characters letting people know we’d be heading to KGB bar for a reading, and then he added hashtag #potbrownies.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

A cab dropped us off outside 8th Street Organic Avenue, a boutique vegan grocery store with pristine white shelving and a hospital vibe except for the smell, like fresh cut lawn. This is the place Tao goes pretty much every day after ingesting Xanax, to buy a chocolate mousse, a coconut yogurt parfait, and a green juice, which costs him $31. “This is so good,” he said, showing me a coconut mousse from a wall of containers that looked exactly alike. We walked several blocks to KGB bar and pushed through a crowd of people waiting to get in the theatre on the floor above. Inside, it was very dark and cool, and we sat in the corner. “I eat the Xanax first because it makes things taste better," he said, eyeing his green juice. I expressed my need for water for the second time in two minutes. “Oh shit,” Tao said, peering into my face, holding straw paper limply between his dry lips. It was the first time in three hours I’d heard him speak in a normal tone of voice and it scared me. A guy came over and shook my hand. Tao said “he saw Twitter, he saw the hashtag, don’t worry" as if that made any sense to me. I was starting to feel like I couldn’t see anything clearly. It took a lot of effort to figure out how I was supposed to leave.

This is what real life looks like, they tell us. This is the job of a writer – to vanquish mess – to inhabit the studio apartment, or the Lower East Side bar of actuality, to pick out a few elements with which to make a story, and consign the rest to the garbage dump. It is wrong, then, to assume that in the presence of a novelist, the experience of them will be the same as how you experienced their stories, as you were reading them. But for Tao Lin that is true. With him in person, no small awkwardness is spared. Images of panic-inducing chaos crop up frequently, not just as metaphors for the failure or absence of meaning, but as advertisements: for his own depression, sense of floating, meaninglessness.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

During the three or so hours we were together, I became drunk and high and moved into a sort of panic, and Tao was fucked up on any number of pills he had taken, plus beer, plus green juice plus another beer, and it was just like his book Taipei. It was just like we were in that book, on our way to some party, susceptible to great mischief and misunderstanding along the way. Barely moving his mouth, he asked if the photographer would stop taking pictures soon, because he was getting too fucked up. I said “What?” not hearing him, or remembering we had been taking photos this whole time.

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

For some years – five or six – Tao was a living person inside my head. For his entire life as a published author, he has been a living person coexisting with his own literary persona. Tao does not do well with it, I think. I do not do well with it, and when I left him at the bar, I left with the memory of someone I quite liked, but felt angry at, and was now worried about, the same way I would worry about a brother in the hospital, or a friend going through a breakup. All the impressions and ideas I have ever had about Tao had been accumulating over the years, and now none of them added up. Riding home over the Williamsburg Bridge, I blamed Tao for being himself, for being just like the characters in his books, because he was violating my creation.

As an author of fiction, his great subject is the tension between falseness and reality. To him it seems there should be nothing but the present. There should be no dividing line between reality and parody of truth, no shield in real life or fiction that says life is not fucked and death is not near. He doesn’t write, as some authors do, to invent a world in which things that are pristine and mythical and inconclusive are the dominant matters of concern. He does not wish to pick out parts and dispose of the rest in order to make a story. He imposes narrative on his own life - all of it – and the stories are concrete, and they are sometimes boring, and, as with Taipei, they drag. His work says, this is what it is, right here. I am showing you. Everything adds up. “Real life.” And yet, there is a sneaking suspicion, just as I have right now, writing this, that I am missing something. The novelist, even as he tries not to, exists in two forms - both himself, and as author - and one cannot know for sure which side of him - the one that sleeps through his flight and misses his book readings, the one that ingests many drugs, the one that fell in love so hard he eloped, the one that shamelessly self-promotes - is putting on a show or being earnest. And that is the mark of a good fiction writer: the one that never lets us fully accept the work. The one that leaves us questioning if we really understood what we just read, and how much about life, about people, about the author, we can really ever know.

Cass Daubenspeck is a contributor to This Recording. This is her first appearance in these pages. She is a writer and editor living in Brooklyn. She can be found in many bars. She interviews people about their private lives here. You can find her twitter here. You can find her website here.

Photographs by Sharokh Mirzai.

"Oregon Trail" - Bad Banana (mp3)

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

photo by Sharokh Mirzai

cass daubenspeck,

cass daubenspeck,  tao lin

tao lin