MUSIC

MUSIC In Which This Is The Fifth or Sixth Time Around For Bob Dylan

Sunday, October 25, 2009 at 12:17PM

Sunday, October 25, 2009 at 12:17PM

And Man Gave Names To All The Animals

by ANDREW ZORNOZA

It is not clear if they are hobos, farmers, or townsfolk, but it is clear that they are four people down on their luck, and they stare out from the movie screen like dustbowlers from a Walker Evans' photograph. In the background, a weathered gray barn yearns for the sky. An American ruin, completing the picture.

I live in paved-over Brooklyn. The word "Americana" conjures in me, for no rational or defensible reason, the photographed image of that lone man standing in front of tanks at Tienanmen Square. Except that, in my mind, the tanks are actually rolling down Flatbush Avenue and the man is Chris Rock, stripped to his underwear.

Parenthetically, I do not think of Woody Guthrie's hardscrabble narratives or Osh-Kosh overalls.

But this is a movie and that means the picture is moving. A distinctly unamerican giraffe now enters the scene, serenely chewing on nothing at all as he poses behind the barn. Apropos of what?

The camera then pans out to take in a bandstand, where a man in white-face deeply contemplates the wood at his feet. The man in white-face wears a tight red jacket with gold tassles—an outfit that A) is so beaten it looks like it has survived the bombing of Dresden B) is of indeterminate purpose: circus? parade? military? It's impossible to tell.

He sings in a deep,reverberating voice. Cerebral gears engage, churning through this inversion of minstelry—but are wrenched to a stop by a pleasant moment of recognition.

The man is Jimmy James, lead singer of My Morning Jacket. As Jimmy's song reaches a most achingly beautiful moment, he stretches out one single word: “Acapulco.” A cover. One of the most awful Dylan tunes of all time—on a first listen. A moment later, the song continues, beautiful once again—wait, wasn't this song awful?

I'm Not There is a glorious trainwreck of a movie. How it avoided going straight to DVD is more a testimony to the purchasing power of Dylan's army of committed fanboys and fangirls than it is to Todd Haynes art-house credentials.

But thank god for the fans—how long has it been since we've had a movie this self-conscious and painful? There is even a brief scene here with Black Panthers' Bobby Seale and Huey Newton waxing philosophical on "Ballad of a Thin Man." I practically could smell the marijuana smoke of the past wafting over the TV, over the Betamax case for Godard's Sympathy for the Devil....

What a great, brave, not-so-little, movie Todd Haynes has given us! This film addresses fame and persona more clearly (with a more challenging subject) than a million Basquiats and Walk The Lines and Fridas and Capotes and Pollocks all put together.

Dylan is largely an idiotic moron here, yet there's the nagging sense that he's onto something.

He is in some sort of purgatory, doomed to sing for eternity (excepting cigarette breaks marred by Samuel Beckett hitting him over the head with the Unnameable).

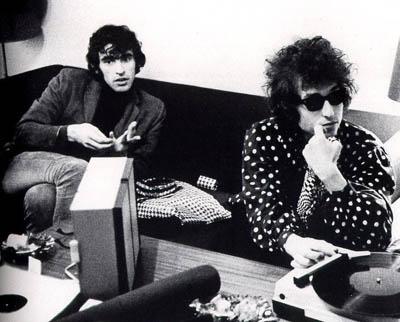

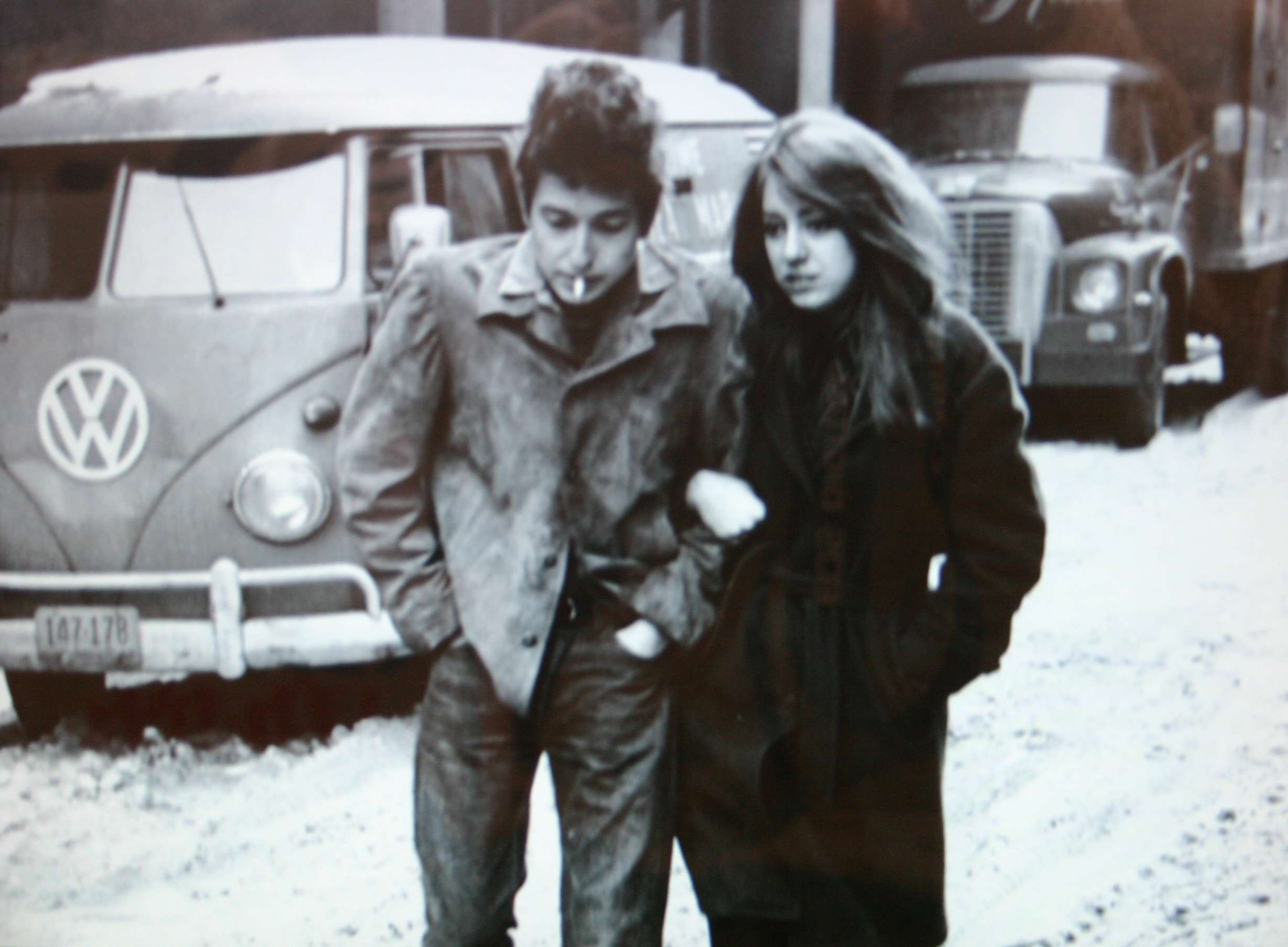

He clearly has put up a front all these years, but behind all of the strutting and nonsense and intimidation so clearly chronicled in Don't Look Back and Eat The Document...despite this and Dylan having the strongest aversion to being pinned down of any performer of our time...Dylan's off-stage inanities are as illuminating as his songs.

Definitions are the enemy of art. Words are definitions. We are surrounded by building blocks but are not blocks ourselves. We are vessels. Love minus zero equals no limit. Don't follow leaders. Watch your parking meters. The pump don't work cause the vandals stole the handle. Et cetera, et cetera.

Dylan's non-stop devil's advocacy and psycho babbling were not an act of distancing himself from the public. They were an intimate demonstration of method.

In order to get his songs balancing on multiple bleeding edges (irrational/rational; contemporary/past, emotional/intellectual) he had to dip into a primordial subconsious soup of armchair philosophy, Americana, and honest to goodness feelings.

And that's what poured out of the idiotic wind between his teeth when he was away from the stage. Everyone tuned him out or took him far too seriously then -- but the secret was there: you can't make sense out of soup, you just got to eat it.

You're not allowed to think very much in the current model of biography pictures. Even if Ray or Capote is shown to be flawed, the flaws are neatly presented. There is no real mystery. Citizen Kane has one sled named Rosebud that appears in two brief moments, these movies have battalions of sleds that encircle and follow the reader at every turn.

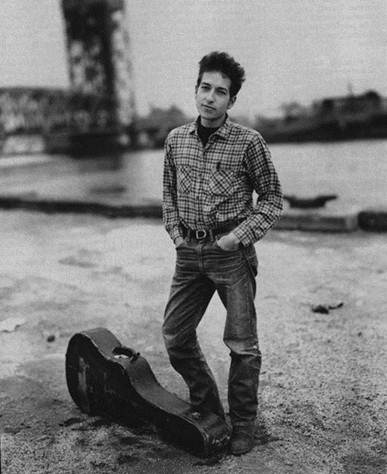

Todd Haynes has left the riddle behind and for that he should be applauded. Haynes insists that the young Bob Dylan was a slight black boy with the name of Woody Guthrie who carried around a guitar case that says, "This Machine Kills Fascists." What could be more ludicrous? Or better?

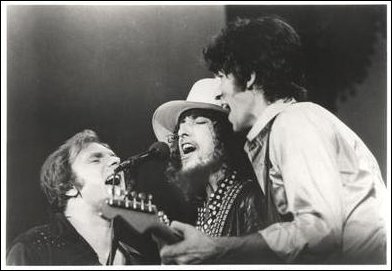

After being jeered as a Judas to the folk movement during the Free Trade Hall concert of May 17th 1966 (and having fans almost boo him off the stage), Dylan turns to Robbie Robertson and says, "Play fucking loud." The thump of Rick Danko's bass and Mickey Jones' drums drowns out the crowd in a decisive whoomp!

How little we knew then of who was on the right side. And how little it matters, if you're down in it.

Truthfully, I wasn't alive then. I have only experienced Dylan first-hand in Victoria's Secret commercials. Which is something like meeting Walt Whitman in a supermarket. It doesn't get much more surreal than that, does it?

Andrew Zornoza is the senior contributor to This Recording. He is the author of the photo-novel Where I Stay available from Tarpaulin Sky Press. He lives in Carroll Garden.

"Lay Lady Lay" - Bob Dylan (mp3)

"I Threw It All Away" - Bob Dylan (mp3)

"Peggy Day" - Bob Dylan (mp3)