FILM

FILM In Which Chemical Photography Dies And Is Reborn Again

Thursday, September 30, 2010 at 11:02AM

Thursday, September 30, 2010 at 11:02AM

The Rumors of Film's Demise...

by JON EDWARD MILLER

"Why would anyone still shoot film?" is a question I get asked a lot. So when This Recording asked me to write something on film, photography and what we were thinking when we created Funeral Photography, my first reaction was crossover episode, sweet! This is totally going to be like one of those Magnum P.I. guest appearances on Murder She Wrote.

Funeral Photography discussing our favorite film stocks with This Recording

But then I cringed, Funeral Photography is a photo blog dedicated to the quickly vanishing art of chemical photography. What if TR expected a long tirade against the evils of the new digital imaging with a link to an all vinyl podcast at the bottom? Maybe with a snappy title like "Analog or Death!" To avoid this I want to start by saying that digital photography is awesome. Seriously, I am using all three definitions of awesome at the same time here, not just the colloquial affirmative declaration.

I do feel a certain pressure to recognize the incredible innovations of digital photography. To ignore it would open the site up to easy dismissal; just a couple film fetishists fighting against an unavoidable future. But if you have delved into the history of photography you'll also know this transition from one photographic recording technique to another, in this case from celluloid to digital sensors, is nothing new. In fact celluloid photography was invented as a cheap, practical and democratic alternative to glass plate photography and was widely decried for creating an inferior image.

Spread chemical emulsion evenly on your iPad to get a similar image, trust me.

Technical innovations in photography have been mothballing their predecessors since the beginning. Just ask Kodak, the inventor of celluloid roll film, which now produces digital cameras and printers. At this point Kodak makes enough money from its chemical patents, medical imaging, etc. that it has already forgotten that you haven’t loaded a roll of film since you took that photo class in high school.

You like x-rays? So do Kodak shareholders.

The unavoidable truth is that most casual photographers haven’t shot film in almost 10 years. That Polaroid profile pic is from your iPhone’s hipstamatic app. For the average consumer who wants to take photos of their friends being stupid, post it on the facebook/flickr/tumble/tweet and tag them, this is not bad news. In fact it has been awesome, but this time only in the colloquial sense.

This photo was taken digitally, need I really say more?

The irony of starting a website dedicated to the film emulsion is not lost on me. But hey I think blinkers on Amish horse and buggies are the single greatest argument for American exceptionalism.

Your loss English.

To clarify, the exact reason that I started this article by singing the praises of digital photography is that Funeral Photography is not trying to launch a Luddite movement against the digital camera, just the opposite. Funeral Photography is interested in documenting and promoting celluloid’s place in 21st century photography.

Funeral-Photography building its website, take that technology!

There are dozens of arguments given by film purists, mostly using vague allusions to the “soul” of emulsion or “intangible essence” of film. The other regularly cited explanation is some sort of nostalgia for a “purer”, “truer” photography that the chemical process evokes. I find both of these arguments dubious, although in America’s nostalgia obsessed culture of Mad Men, Boardwalk Empire, ESPN Classic and Tea Party activists it’s pretty hard to produce anything without evoking a vague sense of loss for something you never had.

Dr. J making white guys nostalgic for the two-handed bounce pass.

I’m not bold enough to totally deny nostalgia as an influence. But rather than focus on the feel good/feel bad emotional arguments that relegate film photography to the status of model trains and stamp collections; there are three things I would ask people to consider before we declare celluloid film dead.

The first, and simplest, is that this isn’t an either/or situation. I shoot both digital and film. Putting emotional preferences for or against celluloid aside, while they can be used to similar effect, they are in fact different mediums. Acrylic paints didn’t result in the end of oils or watercolors.

This grain structure kills fascists.

The grain structure of celluloid film will always be different than the pixel structure of a digital sensor and so will the resulting images from both. The process by which silver halide crystals react to light will never be quiet the same as a digital chip registering visible portions of the electromagnetic spectrum.

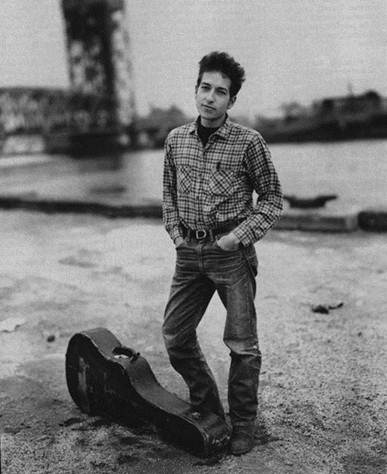

Judas!

Whether one is “better” or not doesn’t interest me. What does interest me, is that the person taking the photograph has bothered to make a choice between the two. What is the subject and objective that motivated the photographer to choose film as the medium and what is the result? As long as those technical differences motivate a decision I am interested in the work of those photographers.

The second is to realize that shooting film is still embracing new technology. Film has never been better, unlike some vague argument for the “richness” of your vinyl record collection, film stocks are faster, have finer grain, more detail and provide a more vivid and dynamic color space than ever before. Chemical photography has continued to evolve since inception.

This advantage is actually even more obvious in film being used for motion pictures. Film emulsions used for motion picture cinematography is enjoying some really exciting technical innovations currently, and using digital technologies to achieve them.

Finally, shooting film forces the photographer into different habits. The medium we choose structures the way we see and in the end that is the value of a photograph, a record of one individuals perception of a moment. For better or worse every photograph taken on film has arguably a higher inherent value to the photographer than on digital, both economically and practically.

CobraSnake doesn’t happen without digital cameras… and cocaine.

Film rolls on 35mm do not go above 36 exposures; the average compact flash card provides the photographer with hundreds of possible exposures. After the initial investment in the camera those digital images are free; in fact the more you take, the more cost effective the card and camera have become, whereas each film roll shot presents a significant cost in development and new film purchases.

She should totally make this her profile pic, right?

With film, you are looking at hours to days before you see the images you captured, as a photographer you must be able to decide whether or not you “got the shot” based on what you remember seeing through the lens. Each shot on film is a gamble not presented to the digital photographer and series of minute cost/benefit analyses, repeated over and over.

For many photographers and cinematographers these limitations are the exact reason to go digital. For some photo-journalists and documentarians digital is often a no-brainer. But it is these limitations, and their influence on the images produced by the artists using film that fascinate me. Shooting film fundamentally changes the photographer and Funeral Photography is dedicated to finding those images and sharing the work of photographers who still find chemical film is a viable medium.

Jon Edward Miller is a contributor to This Recording. This is his first appearance in these pages. He is a cinematographer, photographer and co-editor of Funeral Photography. His cinematography can be seen here. He tweets here. You can e-mail him here.

"The Ghost Who Walks" - Karen Elson (mp3)

"The Ghost Who Walks" - Karen Elson (mp3)

"Pretty Babies" - Karen Elson (mp3)

"The Truth Is In The Dirt" - Karen Elson (mp3)