BOOKS

BOOKS In Which James Agee Found No Single Word For What He Meant

Monday, March 21, 2011 at 11:36AM

Monday, March 21, 2011 at 11:36AM

Plans for Work: October 1937

by JAMES AGEE

The following was submitted by James Agee with his application for a Guggenheim Fellowship.

I am working on, or am interested to try, or expect to return to, such projects as the following. I shall first list them, then briefly specify a little more about most of them.

An Alabama Record.

Letters.

A Story about homosexuality and football.

News Items.

Hung with their own rope.

A dictionary of key words.

Notes for color photography.

A revue.

Shakespeare.

A cabaret.

Newsreel. Theatre.

A new type of stage-screen show.

Anti-communist manifesto.

Three or four love stories.

A new type of sex book.

"Glamor" writing.

A study in the pathology of "laziness."

A new type of horror story.

Stories whose whole intention is the direct communication of the intensity of common experience.

"Musical" uses of "sensation" or "emotion."

Collections and analyses of faces; of news pictures.

Development of new forms of writing via the caption; letters; pieces of overheard conversation.

A new form of "story": the true incident recorded as such and an analysis of it.

A new form of movie short roughly equivalent to the lyric poem.

Conjectures of how to get "art" back on a plane of organic human necessity, parallel to religious art or the art of primitive hunters.

A show about motherhood.

Pieces of writing whose rough parallel is the prophetic writings of the Bible.

Uses of the Dorothy Dix method, the Voice of Experience: for immediacy, intensity, complexity of opinion.

The inanimate and non-human.

A new style and use of the imagination: the exact opposite of the Alabama record.

A true account of a jazz band.

An account and analysis of a cruise: "high"-class people.

Portraiture. Notes. The Triptych.

City Streets. Hotel Rooms. Cities.

A new kind of photographic show.

The slide lecture.

A new kind of music. Noninstrumental sound. Phonograph recording. Radio.

Extension in writing; ramification in suspension; Schubert 2-cello Quintet.

Analyses of Hemingway, Faulkner, Wolfe, Auden, other writers.

Analyses of review of Kafka's Trial; various moving pictures.

Two forms of history of the movies.

Reanalyses of the nature and meaning of love.

Analyses of miscommunication; the corruption of idea.

Moving picture notes and scenarios.

An "autobiographical novel."

New forms of "poetry."

A notebook.

In any effort to talk further about these, much is liable to overlap and repeat. Any further coordination would however be rather more false than true indication of the way the work would be undertaken; for these projects are in fluid rather than organized relationship to each other. None of the following can be more than suggestive of work.

Alabama Record.

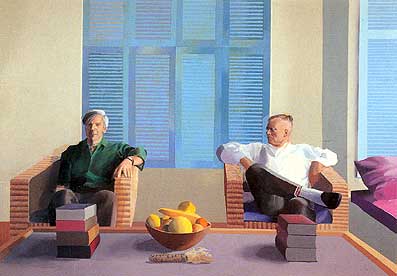

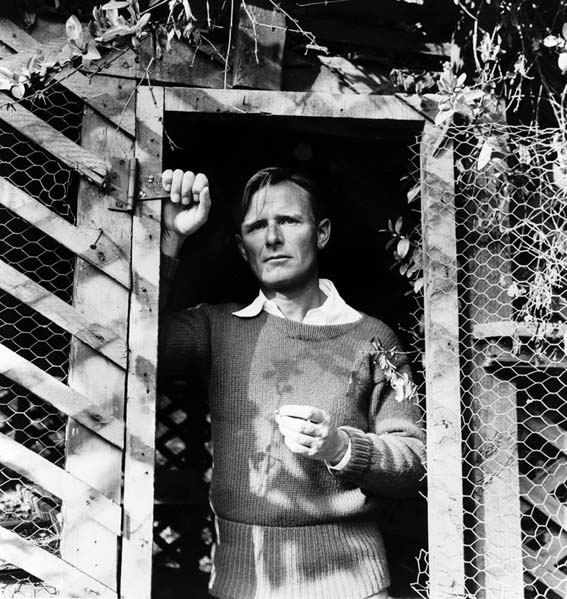

In the summer of 1936 the photographer Walker Evans and I spent two months in Alabama hunting out and then living with a family of cotton tenants which by general average would most accurately represent all cotton tenancy. This work was in preparation for an article for Fortune. We lived with one and made a detailed study and record of three families, and interviewed and observed landowners, new dealers, county officers, white and negro tenants, etc., etc., in several cities and county seats and villages and throughout 6,000 miles of country.

The record I want to make of this is not journalistic; nor on the other hand is any of it to be invented. It can perhaps most nearly be described as "scientific," but not in a sense acceptable to scientists, only in the sense that it is ultimately skeptical and analytic. It is to be as exhaustive a reproduction and analysis of personal experience, including the phases and problems of memory and recall and revisitation and the problems of writing and communication, as I am capable of, with constant bearing on two points: to tell everything possible as accurately as possible: and to invent nothing. It involves therefore as total a suspicion of "creative" and "artistic" as of "reportorial" attitudes and methods, and it is therefore likely to involve the development of some more or less new forms of writing and of observation.

Of this work I have written about 40,000 words, first draft, and entirely tentative. On this manuscript I was offered an advance and contract, which I finally declined, feeling I could neither wisely nor honestly commit the project to the necessarily set or estimated limits of time and length. With your permission I wish to submit it as a part of my application, in the hope that it will indicate certain things about the general intention of the work, and also some matters suggested under the head of "accomplishments," more clearly than I can. I should add of it a few matters it is not sufficiently developed to indicate.

Any body of experience is sufficiently complex and ramified to require (or at least be able to use) more than one mode of reproduction: it is likely that this one will require many, including some that will extend writing and observing methods. It will likely make use of various traditional forms but it is anti-artistic, anti-scientific, and anti-journalistic. Though every effort will be made to give experience, emotion and thought as directly as possible, and as nearly as may be toward their full detail and complexity (it would have at different times, in other words, many of the qualities of a novel, a report, poetry), the job is perhaps chiefly a skeptical study of the nature of reality and of the false nature of re-creation and of communication. It should be as definitely a book of photographs as a book word, in other words photographs should be used profusely, and never to "illustrate" the prose. One of part of the work, in many senses the crucial part, would be a strict comparison of the photographs and the prose as relative liars and as relative reproducers of the same matters.

Letters.

Letters are in every word and phrase immediate to and revealing of, in precision and complex detail, the sender and receiver and the whole world and context each is of: as distinct in their own way, and as valuable, as would be a faultless record of the dreams of many individuals. The two main facts about any letter are: the immediacy, and the flawlessness, of its revelations. In the true sense that any dream is a faultless work of art, so is any letter; and the defended and conscious letter is as revealing as the undefended. Here then is a racial record, and perhaps the best available document of the power and fright of language and of miscommunication and of the crippled concepts behind these. The variety to be found in letters is almost as unlimited as literate human experience; their monotony is equally valuable.

Therefore, a collection of letters of all kinds.

Almost better than not, the limits of this would be: what you and your friends and their acquaintances can find. For even within this, the complete range of society and of mind can be bracketed; and this limitation more truly indicates the range of the subject than any effort to extend it onto more ordinary planes of "research" possibly could.

Working chiefly thus far with two or three friends, we have got together many hundreds of letters. Many more are on their way.

There are several possible and equally good methods of handling these letters.

1. Beyond deletion of identifiers, no editing and no selection at all. In other words, let chance be the artist, the fulcrum and shaper. This is beyond any immediate possibility of publication, in any such bulk.

2. Very careful selection, the chief guides to be a scientific respect for chance and for representativeness rather than respect for more conventional forms of "reader interest"; and (b) the induction and education of a reading public, for less selected future work.

3. Context notes, short and uncolored, would probably be useful.

4. Take certain or all such letters. Let them first stand by themselves. Then an almost word by word analysis of them, as manysided and extensive as the given letter requires. This could be of great clarifying power.

5. Instead of a purely "scientific" analysis, one which likewise allows the open entrance of emotion and belief, to the violent degrees for instance, of rage, rhapsody and poetry.

6. A series or book of invented letters, treated in any or all of the above ways.

These treatments may seem to cancel each other. Not at all necessarily. I would hope to use them all in the course of time, and very likely would try substantial beginning-examples of all in the same first volume.

The value or bearing of such work would come under my own meanings of science, religion, art, teaching, and entertainment.

It should also help to shift and to destroy various habits and certitudes of the "creative" and of the "reading," and so of the daily "functioning" mind.

It could well be published in book form or as all or as part of a certain type of magazine I am interested in, or as a part of a notebook which I shall say more of later.

As a book it should even in its first shot contain as much as a publisher can be persuaded to allow; and its whole demeanor should be colorless and noncommital, like scientific or government publications. It should contain a great deal of facsimile, not only of handwriting but of stationary.

A story about homosexuality and football.

Not central to this story but an inevitable part of it would be a degree of cleansing the air on the subject of homosexuality. Such a cleansing could not in this form hope to be complete. The same clarifying would be attempted on the sport and on the nature of belief: always less by statement than by demonstration. All this however is merely incidental to the story itself.

An account, then, of love between a twelve year old boy and a man of twenty-two, in the Iliadic air of football in a Tennessee mountain peasant school: reaching its crisis during and after a game which is recounted chiefly in terms of the boy's understanding and love; in other words in terms of an age of pure faith. The prose to be lucid, simple naturalistic and physical to the maximum possible. In other words if it succeeds in embodying what it wants to it must necessarily have the essential qualities of folk epic and of heroic music carried in terms of pure "realism." This is being written now. It is to be about the length and roughly the form of the "long short story."

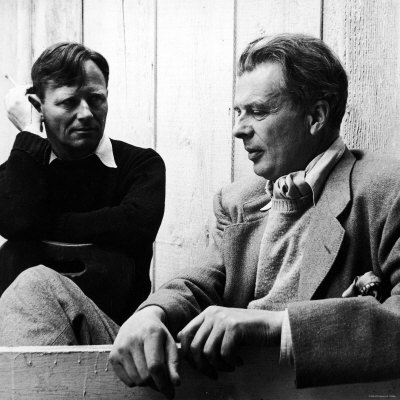

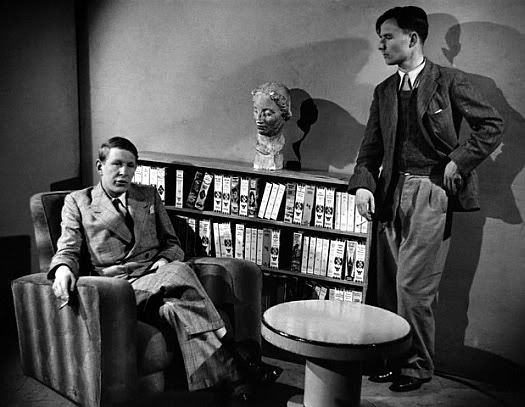

time staff writers, 1945News Items.

time staff writers, 1945News Items.

Much the same as Letters.

Hang with their own rope.

I have found no single word for what I mean. The material turns up all over the place. The idea is, that the self-deceived and corrupted betray themselves and their world more definitively than invented satire can. Vide Eleanor Roosevelt's My Day; Mrs. Daisy Chanler's Autumn in the Valley; the journal and letters of Gamaliel Bradford; court records, editorial, religious, women's pages; the "literature" concerning and justifying the castration of Eisenstein; etc.

Such could again be collected in a volume, or as a magazine or part of a magazine; or in the notebook. The above is limited to self-betrayals in print. Those in unpublished living must of course be handled in other ways. One minor but powerful way is, the unconsciously naked sentence, given either with or without context. These are abundant for collection.

A dictionary of key words.

More on the significance of language. Add idioms. A study and categorizing of tones of voice, or rhythms and of inflection; of social dialects; would also be useful. Key words are those organic and collective belief - and conception - words upon the centers and sources of which most of social and of single conduct revolves and deceives or undeceives itself and others. Certain such words are Love, God, Honor, Loyalty, Beauty, Law, Justice, Duty, Good, Evil, Truth, Reality, Sacrifice, Self, Pride, Pain, Life, etc. etc. etc. Such would be examined skeptically in every discernible shade of their meaning and use. There might in a first dictionary be an arbitrary fifty or a hundred, with abundant quotations and examples from letters, from printed matter, and from common speech.

Mr. I. A. Richards, whose qualifications are extremely different from my own and in many essentials far more advanced, is, I understand, working on just such a dictionary. Partly because the differences of attack would be so wide, and still more because the chief point is the ambiguity of language. I do not believe these books would be at all in conflict.

Notes for color photography.

Of two kinds: theoretical and specific. For stills; in motion; in coordination with sound and rhythm. Uses of pure color, no image. Metaphoric, oblique, nervous and musical uses of color. Analyses of the "unreality" of "realistic" color photography. Of differences between color in a photograph and in painting. The esthetic is as basically different as photography itself is from painting, and as large a new field is open to color in photography. Examples of all this, and notes for future use, from observation.

A revue.

Much to do with the whole theatrical form. The dramatic stage is slowed and stuffed with naturalism. Audiences still and without effort accept the living equivalent of "poetry" in revue, burlesque and vaudeville. Stylization, abbreviation and intensity are here possible. Destructive examples of "spurious" use: Of Thee I Sing, As Thousands Cheer, etc. Solid examples, upon which still further developments can be made: the didatic plays of Brecht; The Cradle Will Rock; The Dog Beneath the Skin.

Shakespeare.

Commentary; ideas for productino in moving picture and on stage; criticism of contemporary production of his work and of attitudes toward his work produced or read. In movies: use of screen and sound as elliptic commentary or development of the lines. On stage: concentration totally in words and physical relationships. Qualifiedly good example: The Orson Welles Faustus (I have not yet seen his Caesar). On stage also: Savage use of burlesqued melange of traditional idioms of production, conception and reading, intended as simultaneous ridicule, analysis and destruction of culture.

A cabaret.

Cheap drinks, hot jazz by record and occasional performers; "floor show." Examples of acts: monologues I have written; certain numbers from Erika Mann's Peppermill; much in Groucho Marx, Durante, Fields. Broad and extreme uses of ad lib and of parody. No sets, no lighting and only improvised costume. Intense and violent satire, "vulgarity," pure comedy. Strong development of improvisation; use of the audience in this.

Newsreel. Theater.

The theater: 15-25 cents, 42nd street west of Times Square, open all night. Usual arty-theatre repertory much cut down, strongly augmented by several dozen features overlooked by the arty and political, and by several of Harry Langdon's and all of Buster Keaton's comedies. Strong and frequent shifts in "policy," to admit, for instance, a week embodying the entire career of a given director or star or idiom. Revivals, much more frequent than at present, of certain basics: Chaplin, Cagney, Garbo, Disney, Eisenstein. For silent pictures, uses of the old projector, which gives these at their proper speed. Occasional stage numbers and jazz performers. Cheap bar out of sound of screen. Totally anti-arty and anti-period-laugh. Strongly, but secondarily, political. Most of hte audience must be drawn on straight entertainment value, or not at all.

The Newsreeel: Once a month for a week. Clips from newsreels, arranged for strongest possible satire, significance and comedy, with generally elliptic commentary and sound.

New type of stage-screen show.

Using anti-realistic technique of revue and combining and alternating with screen, plus idioms also of radio; proceeding by free association and by naturalistic symbol and by series of nervous emotional and logical impacts rather than by plot or characters; in an organization parallel to that of music and certain Russian and surrealist movies. More direct uses of the audience than I know of so far. Made not for an intellectual but for a mixture of the two other types of audience: the bourgeois, and the large and simple. Such a show should not last more than 40-60 minutes and should have the continuous intensity as well as the dimensions of a large piece of music. I have begun one such, springboarding from the Only Yesterday idiom, and have another projected, on mothers.

Anti-communist manifesto.

Merely a working title. Assumption and statement in the first place of belief in ideas and basic procedures of communism. On into specific demonstrations of its misconceptions, corruptions, misuses, the damage done and inevitable under these circumstances, using probably the method of comment on quotations from contemporary communist writing and action.

Three or four love stories.

Stories in which the concentration would be entirely on the processes of sexual love. If these are "works of art," that will be only incidental.

A new type of sex book.

Beginning with quotations from contemporary and former types, an analysis of their usefulness, shortcomings, and power to damage, and a statement of the limitations of the present book. Then as complete as possible a record and analysis of personal experience from early childhood on, and of everything seen heard learned or suspected on the subject; analyses and extensions of the significance and power of sex and of sexual self-deception; with all available examples.

"Glamor" writing.

Here, as above on love, the concentration on recording and communicating pure glamor and delight.

Pathology of "laziness."

Essentially fiction, but probably much analysis. Its connections with fear, ignorance, sex, misinterpretation and economics. A story of cumulative horror.

A new type of "horror" story.

Not the above, but the horror that can come of objects and of their relationships and of tones of voice, etc, etc. Non-supernatural, non-exaggerative.

Stories whose whole intention is the communication of the intensity of common experience.

Concentration on what the senses receive and the memory and context does with it, and such incidents, done full length, as a family supper, a marital bedfight, an auto trip.

Musical uses of sensation or emotion.

As for instance: A, a man knows B, a girl, and C, a man, each very well. They meet. A is anxious that they like each other. B and C are variously deflected and concerned. All is delicately yet strongly distorted. Their relationship is more complex yet as rigid as that or mirrors set in a triangle, faces inward and interreflecting. These interreflections, as the mirrors shift, are analogous to the structures of contrapuntal music.

Most uses would be more subtle and less describable. Statements of moral and physical sprained equations. This would be one form of poetry.

dinner with the chaplins

dinner with the chaplins

Collections and analyses of faces; of news pictures.

Chiefly the faces would be found in news pictures.

The forms of analysis would be useful, one with, one without, any previous knowledge of whose the face and what the context is. The nearest word for such a study is anthropological, but it involves much the anthropologist does not take into account. The faces alone, with no comment, are another form of value. The pictures of more than face involve much more, which has to do with the esthetics and basic "philosophies" of poetry, music and moving pictures.

One idea here is this: no picture needs or should have a caption. But words may be used detachably, and may be used as sound and image are used with and against each other. And the picture may be used as a springboard, a theme for free variation and development; as with letters and with pieces of overheard conversations.

A new form of movie short.

A form, 2 to 10 minutes long, capable of many forms within itself. By time-condensation, each image (like each words in poetry) must have more than common intensity and related tension. This project is in many ways directly parallel to written "musical" uses of "sensation" and "emotion."

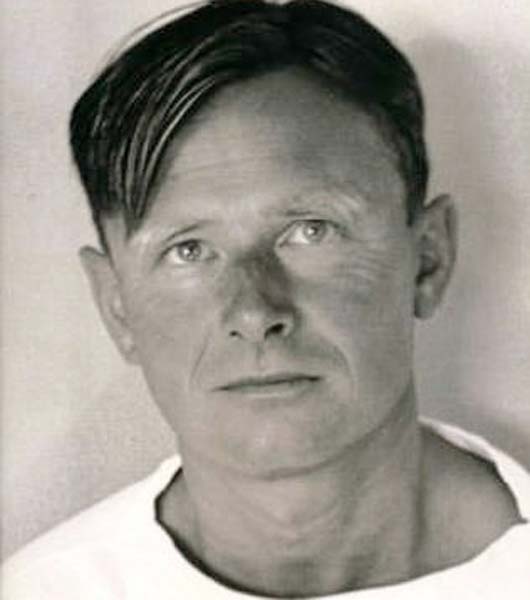

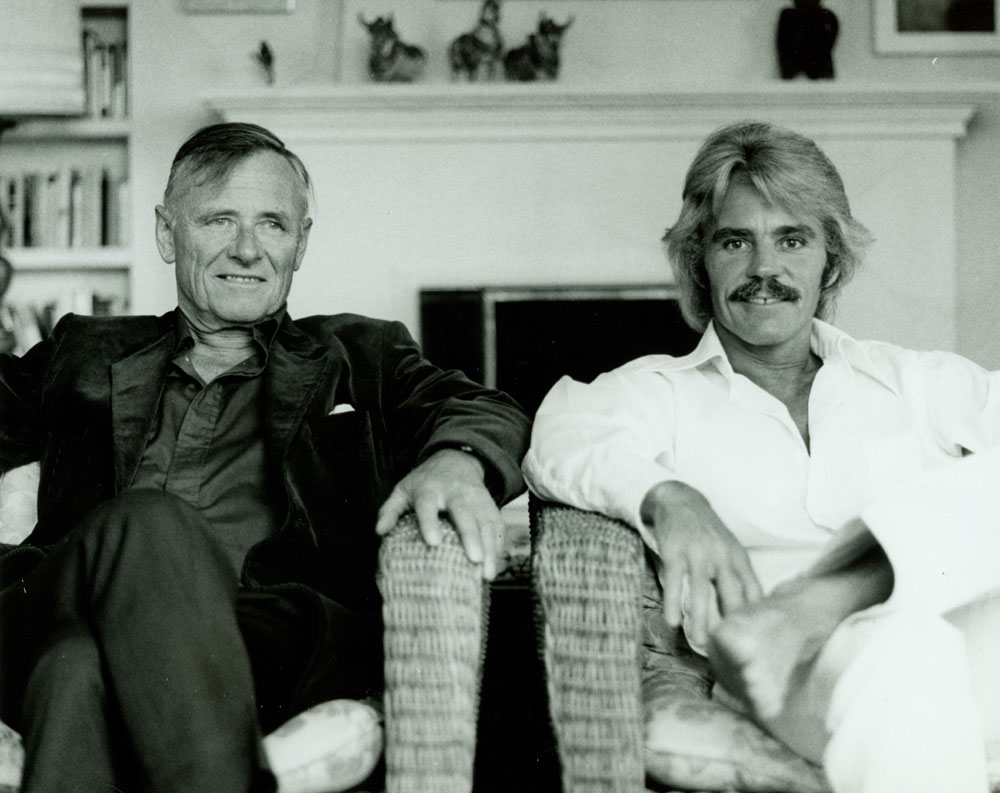

walker evans

walker evans

Conjectures on how to get "art" back on the plane of organic human necessity.

I can write nothing about this, short of writing a great deal. But this again is intensely anti-"artistic," as of art in any of its contemporary meanings. Every use of the moving picture, the radio, the stage, the imagination, and the techniques of the psychoanalyst, the lecturer, the showman and entertainer, the preacher, the teacher, the agitator and the prophet, used directly upon the audience itself, not just set before them: and used on, and against, matters essential to their existence. Such would be the above-mentioned show about motherhood: a massive yet detailed statement of contemporary motherhood and all ideas which direct and impose it.

"Prophetic" writing.

Here too, the directest, most incisive and specific, and angriest possible form of direct address, semi-scientific, semi-religious; set in terms of the greatest available human intensity.

Dorothy Dix: the Voice of Experience

Typical human situations, whether invented or actual, are set up: then, of each, strong counterpoints of straight and false analysis and advice. So, again, as in a letter, each case inevitably expands and entangles itself with a whole moral and social system; the general can best be attacked through the specific. No time wasted with story, character development, etc.; you are deep in the middle from the start, with more immediacy and intensity than in a piece of fiction: inside living rather than describing it.

The inanimate and non-human.

By word, sound, moving picture. Simply, efforts to state systems and forms of existence as nearly in their own, not in human terms, as may be possible: towards extensions of human self-consciousness, and still more, for the sake of what is there.

A "new" style of use of the imagination.

In the Alabama record the effort is to suspect the mind of invention and to invent nothing. But another form of relative truth is any person's imagination of what he knows little or nothing of and has never seen. In these terms, Buenos Aires itself is neither more nor less actual than my, or your, careful imagination of it told as pure imaginative fact. The same of the States of Washington and West Virginia, and of his histories of The Civil War, the United States, and Hot Jazz. Such are projects I want to undertake in this way.

A true account of a jazz band.

The use of the Alabama technique on personal knowledge of a band.

An account and analysis of a cruise: "high"-class people.

Related to the Alabama technique, a technique was developed part way in Havana Cruise, mentioned among things I have had published, I should like to apply this to behavior of a wealthier class of people on, say, a Mediterranean cruise.

Portraits, Notes, The Triptych.

Only photographic portraiture is meant. Notes and analyses, with examples, of the large number of faces any individual has. The need for a dozen to fifty photographs, supplementing five or three or one central, common denominator, for a portrait of any person. Notes on composition, pose and lighting "esthetics" and "psycho" analysis of contemporary and recent idioms.

The triptych: Research begins to indicate (in case anyhow of criminals and steep neurotics) that the left and right halves of the face contain respectively the unconscious and the conscious. So: the establishment is possible of custom, habit, wherin one would have triptychs of one's friends, relatives, etc: the left half reversed and made a whole face; the natural full face; the right-face.

Collections of these, with or without case histories, in a book.

Also: of each person, two basic portraits, one clinical, the other totally satisfying the sitter; to be collected and published.

Also: "anthropological" use of the family album. Of any individual, his biography in terms of pictures of him and of all persons and places involved in his life. A collection of such biographies of anonymous people, with or without case-history notes and analysis.

City streets. Hotel rooms. Cities.

And many other categories. Again, the wish is to consider such in their own terms, not as decoration or atmosphere for fiction. And, or: in their own terms through terms of personal experience. And, or; in terms of personal, multipersonal, collective, memory or imagination.

A new kind of photographic show.

In which photographs are organized and juxtaposed into an organic meaning and whole: a sort of static movie. Scenario for such a show furnished if desired.

The slide lecture.

A lecture can now be recorded and sent around with the slides. The idea is that this can be given vitality as an "art" form, as a destroyer, disturber and instructor.

A new kind of "music."

There is as wide a field of pure sound as of pure image, and sound can be photographed. The range, between straight document and the farthest reaches of distortion, juxtaposition, metaphor, associatives, the specific male abstract, is quite as unlimited. Unlimited rhythmic and emotional possibilities. Many possibilities of combination with image, instrumental music, the spoken and printed word. For phonograph records, radio, television, movies, reading machines. Thus: a new field of "music" in relation to music about as photography is in relation to painting. Some Japanese music suggests its possibilities.

Extension in writing; ramification in suspension, Schubert 2-cello Quintet.

Experiments, mostly in form of the lifted and maximum suspended periodic sentence. Ramification (and development) through developments, repeats, semi-repeats, of evolving thought, of emotion, of associatives and dissonants. The quintet: here and sometimes elsewhere Schubert appears to be composing out of a state of consciousness different from any I have seen elsewhere in art. Of these extension experiments some are related to this, some to late quartets and piano music of Beethoven. The attempt is to suggest or approximate a continuum.

Two forms of history of the movies.

One, a sort of bibliography to which others would add: an exhaustive inventory of performers, performances, moments, images, sequences, anything which has for any reason ever given me pleasure or appeared otherwise valuable.

The other, an extension of this into complete personal history: recall rather than inventory.

Reanalyses of the nature and meaning of love.

Chiefly these would be tentative, questioning and destructive of crystallized ideas and attitudes, indicative of their power to cause pain. Not only of sexual but of other forms of love including the collective and religious. The love stories, the sex book, and part of the dictionary and letters, all come under this head.

Analyses of miscommunication; the corruption of ideas.

Again, to quite an extent, the dictionary, the letters, personal experience, dictaphone records of literal experience, comparison of source writing with writing of disciples and disciplinarians. In one strong sense ideas rule all conduct and experience. Analyses of the concentricities of misunderstanding, misconditioning, psychological and social lag, etc, through which every first-rate idea and most discoveries of fact, move and become degraded and misused against their own ends.

Moving picture notes and scenarios.

Much can be done, good in itself and possibly useful to others, even without a camera and money, in words. I am at least as interested in moving pictures as in writing.

An "autobiographical novel."

This would combine many of the forms and ideas and experiments mentioned above. Only relatively small portions would be fiction (though the techniques of fiction might be much used); and these would be subjected to nonfictional analysis. This work would contain photographs and records as well as words.

Poetry.

This I am unable to indicate much about; but it involves all the more complex and intense extensions suggested by any of the above, and, chiefly, personal recall and imagination. It is in the long run perhaps more important than anything I have mentioned; but includes much of it.

Notebook.

One way of speaking, a catchall for all conceivable forms of experience which can in any way, scientifically, imaginatively, or otherwise, be recorded and analyzed. More than one person could contribute to such a work, and it would be handed ahead to others. It would not at any time be finishable. It would in course of time reach encyclopedic size, or more. It would be published looseleaf, so that readers might make their own inserts and rearrangements as they thought most relevant. Such a record could perhaps best be published by the State or by a scientific foundation.

I would wish, under a grant, to go ahead with work such as this. Most likely the concentration would be on the Alabama record and secondarily on moving pictures, sound-music, and various collections of letters and pictures, and various experiments in poetry. Quite a bit of this work would be done in collaboration with Mr. Walker Evans who is responsible for some and collaboratively responsible for others of the ideas or projects mentioned.

James Agee died in 1955.

"Goldeneye" - Frank Ocean (mp3)

"There Will Be Tears" - Frank Ocean (mp3)

"Swim Good "- Frank Ocean (mp3)