The Diaries of Christopher Isherwood

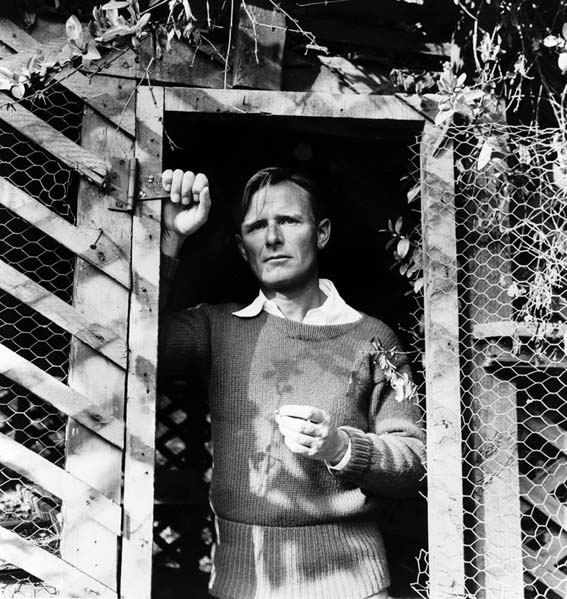

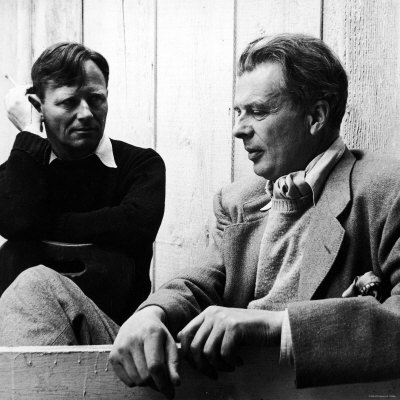

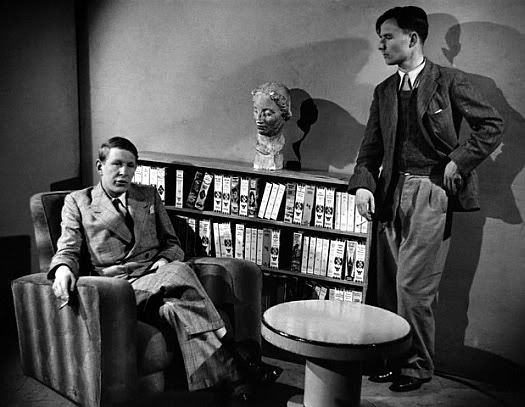

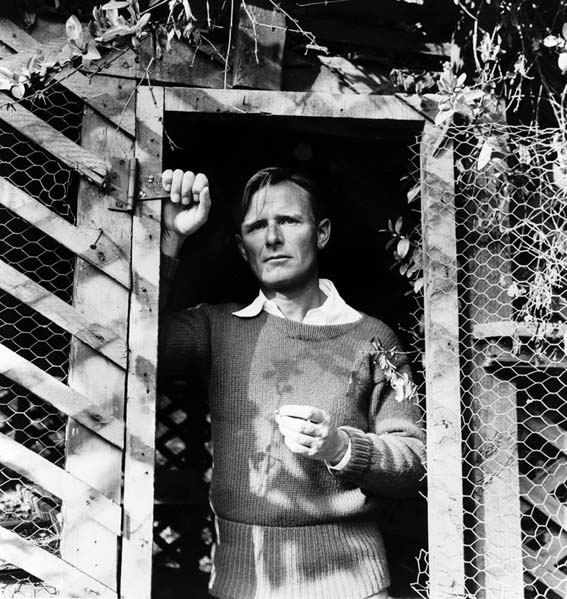

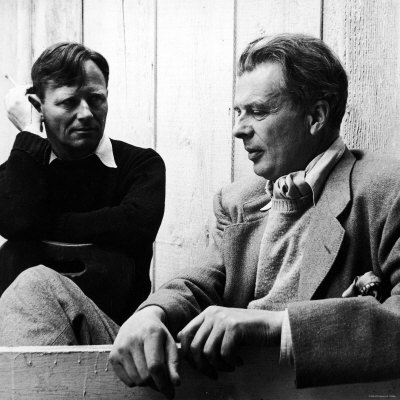

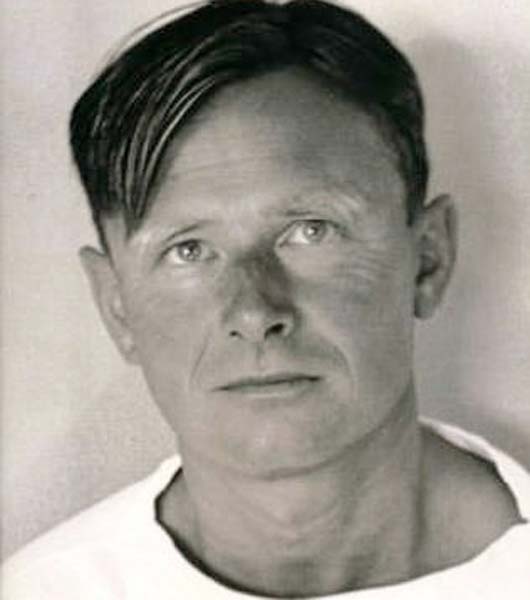

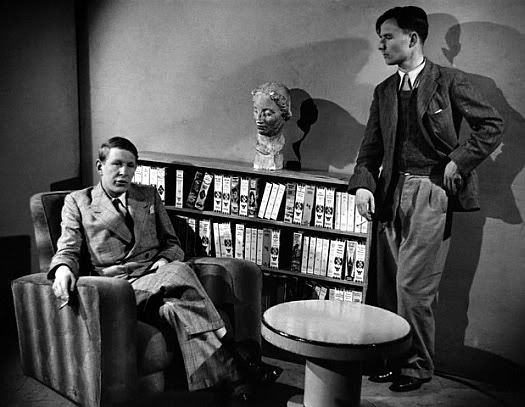

He was as gay as the day is long. Christopher Isherwood and sometime sexual partner Wystan Auden left England for America in 1939 as the Second World War was about to begin in earnest. A supremely accomplished novelist, Isherwood was generous to many young writers, and his novelistic talents are equalled by the kindness of spirit he shows in semi-private writings during his early American years. Isherwood wrote about his life with the idea that eventually it would be put into print, and he even edited the first publication of these journals. What follows are selected entries from the different periods of his life. - A.C.

1940

January 12. The weather is clearing. Blue sky at last, with immense clouds. Spent the day discussing the story with Thoeren; I couldn't put him off any longer. He is a big tomcat of an ex-leading man, who talks endlessly about his love affairs, with a kind of sadistic vulgarity. His attitude of cynical self-abasement amounts to saying, "I'm dirt myself. Therefore anyone who sleeps with me is less than dirt." He is a liar, but intelligent. We shall probably get along quite well together.

January 13. Thoeren and I had another interview with Hyman. We were taking about our hero's inferiority complex. Suddenly, Hyman started to tell us a story.

When he was a schoolboy, his best friend had a girl, and this girl had a sister. The first time Hyman saw her, he fell for her. "She was a perfect assembly of womanhood." Soon he was so much in love that he gave up making dates with her; he felt it was quite hopeless — there were so many rich, goodlooking boys around. Then, to his amazement, she sent for him and asked why he was staying away from the house. He told her the truth. She said, "I'm glad — because I've been in love with you for a long time."

In the same town there lived a very rich man, twenty years older than Hyman, who, for twelve years, had been unhappily married to an invalid wife. The wife died. The rich man met Hyman's girl at a party and fell passionately in love with her. He came to Hyman and appealed to him, humiliating himself before the schoolboy. "If you really care for her happiness, give her to me. Think of all the things I can offer her." The widower's relatives and friends joined in the campaign; they carried the girl off to spend a weekend with them. The girl telephoned Hyman: "If you still care for me at all, come and take me away." But Hyman did nothing. The rich man's arguments had convinced him. He never saw her again.

A year later, the widower and the girl got married. They have been happy. The girl now has grown-up sons. Her elderly husband has lost most of his money. Hyman is earning two hundred and fifty thousand dollars a year.

Once, quite recently, he spoke to her, on the phone. She was very gay and "said all the wrong things." She also had a long conversation with Hyman's wife. Bernie told all this so modestly and simply that, for the moment, he seemed quite charming. The question is: how often does he tell this story, and to whom?

All day I have been happy. Chiefly because this morning, driving through the cold sunshine in our open car to the studio, I saw, far behind Hollywood, for the first time, the snow-covered mountains. "Look at them!" I kept repeating excitedly, to a hitchhiker I'd picked up. He agreed politely that they were pretty.

Mrs. MacCabe treated us to a turkey dinner. Happy chattered all through the meal — about aviation, sailing, automobiles, and the good times he'd had with his friend. "Boy, I had more fun — !" He has to have several shots a day for his diabetes, but he is exactly like any ordinary, healthy boy. It never occurs to him to feel sorry for himself. (It never occurs to me not to.)

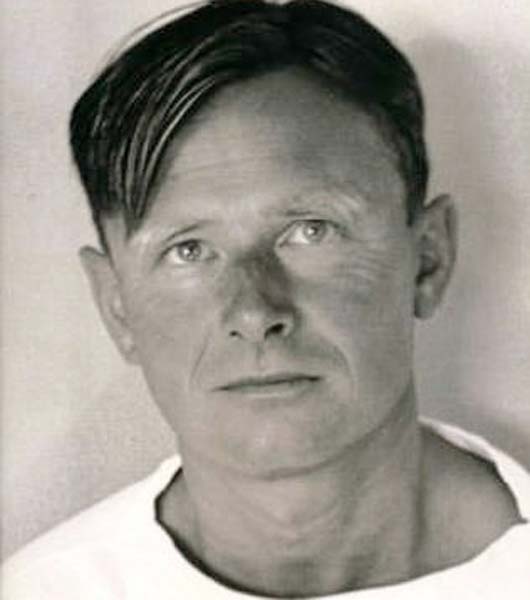

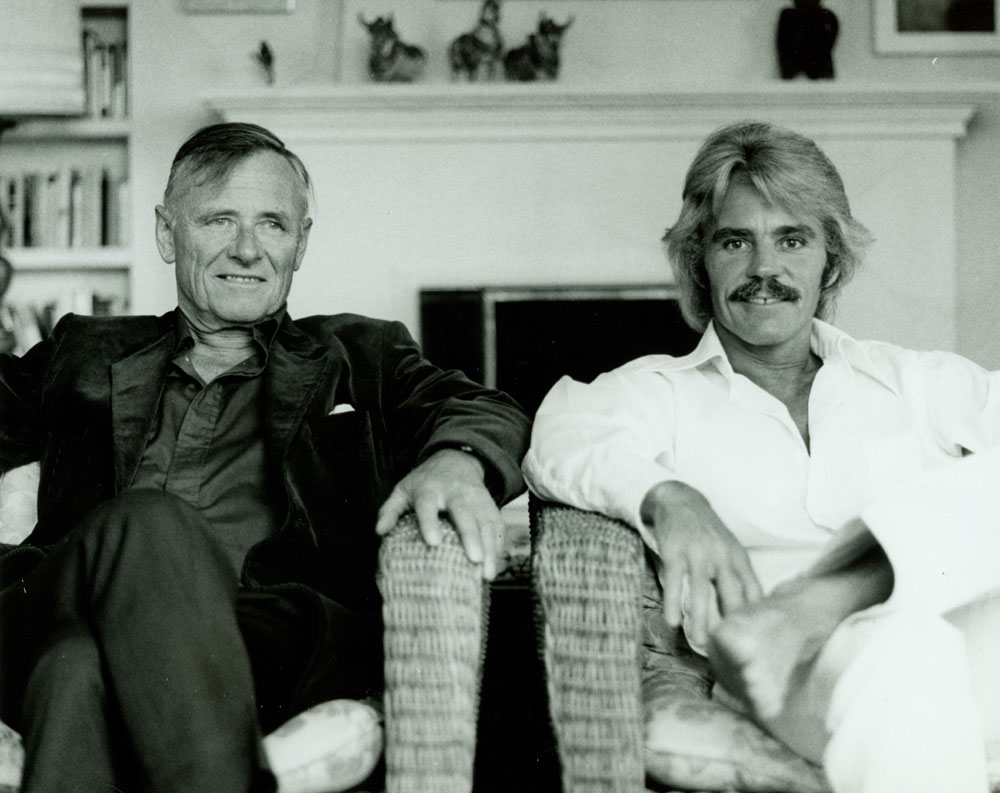

January 15. Lunch with Huxley. Now that he is getting over his shyness, he is charming. We talked about the Bardo Thodol, which he has been reading lately. An old lady sold us bunches of artificial violets. I gave mine to Frau Bach, who said, "You're fortunate that I don't reward you with a kiss!"

January 25. In the afternoon, I went to Chaplin's studio. Chaplin was in a talkative mood. He repeats himself, amplifies, contradicts. (Meltzer later imitated him saying: "The only thing I can say for myself is — I've never been melancholy. Never. Of course, everybody is melancholy around the age of twenty. When I was twenty-one, I was terribly melancholy. I was melancholy until I was thirty. Well, no — not exactly what you could call melancholy. I'm never melancholy, really...etc, etc.")

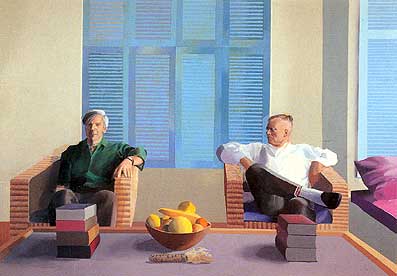

July 21. Vernon and I dined at the Huxleys'. Maria served cold supper to a crowd of boys and girls — Matthew's friends. Aldous and I talked in a corner about Lengyel's dramatization of Lady Chatterly's Lover. He wants us to help him with it. The boys gaily bullied Vernon for liking Picasso. For some mysterious reason, the party was a success: the psychic currents were flowing harmoniously.

July 24. Down to RKO to see Stevenson, that smiling young renaissance cardinal, and Lipscomb, the actor-cricketer. We discussed the final details of the horror story for the British relief picture.

In the afternoon, I lay on the beach among the crowd. The old lady telling her sister what the rabbi said about her talented grandson; the youths bribing their kid brother with a candy bar to ask an attractive girl the time; the boys turning somersaults with an inner tub as a springboard, watched admiringly by an elderly man and his wife; the handball players, jostling and cursing; the lifeguard's Newfoundland dog; the Japanese brothers wrestling, with vague, oriental smiles; Nellie who keeps the hot-dog stand and was born in Sheffield; the kids with their tough talk: "Aw — what the heck. Park the junk here." No one is excluded. We are all welcome to the sunshine, and the dirty ocean with its dazzling surf, full of seaweed and last night's discarded rubbers.

November 12. Headache this evening, and rheumatism in my hip. So I did my meditation sitting upright in a chair in my room. Perhaps because of the headache, concentration was much easier than usual. I suddenly "saw" a strip of carpet, illuminated by an orange light. The carpet was covered with a black pattern, quite unlike anything we have in the house. But I could also "see" my bed, standing exactly as it really stands. My field of vision wasn't in any distorted.

As I watched, I "saw," in the middle of the carpet, a small dirty-white bird, something like a parrot. After a moment, it began to move, with its quick stiff walk, and went under the bed. This wasn't a dream. I was normally conscious, aware of what I "saw" and anxious to miss no detail of it. As I sat there, I felt all around me a curiously intense silence, like the silence of deep snow. The only sinister thing about the bird was its air of utter aloofness and intention. I had caught it going about its business — very definite business — as one glimpses a mouse disappearing into its hole.

1941

July 19. Beginning of sex dream with B. But this turned into a parting, and I saw B. go off with someone else, without regret. Woke at 4:30. First watch, one hundred twenty minutes, medium poor.

Read headlines at drugstore. Usual pointless despair. Must concentrate every moment on interior life. Avoid daydreaming. This idiotic desire to run upstairs, see what's doing, and run down again, like a chicken without a head.

Weekend disturbance. Many of the others plan to get away and "relax." But the real relaxation would be to stay here and try to calm myself inside.

April 22. Rene has separated from his wife, Esther: they maintain a queer, teasing relationship. She comes down to visit him every now and then, and they make love violently, after which his back hurts more than ever and they quarrel. Esther is very attractive and intelligent and funny. I met her the other day.

Rene lives in an apartment at the top of a house built in what Pete calls "Early Frankenstein." It has queer Gothic dormer windows and black eaves like the wings of bats. In the daytime it merely looks shabby; at night it is terrifying, especially by moonlight.

May 3. Carved in the wall of the Meeting House, near my usual seat, is a heart, with the initials R.D.B., J.L.R. After Meeting, one of the neighbors, Dr. Wilson, introduced me to an elderly gentleman who has the job of inspecting any cargo of birds or animals which arrives at the port of Philadelphia. His last assignment was a thousand monkeys from South Africa. He is very proud of his new harbor permit, issued since the war began, with his photograph and fingerprints. An Ibsen character.

Elizabeth and Ruth, after dark, destroying the nests of caterpillars in the big apple tree with a kerosene flare at the end of a long bamboo pole.

May 24. Now that the warm weather has come, the ladies at the Meeting House use leaf-shaped fans of cardboard or basketwork. The lady who sits in front of me has a fan with a picture of Frances E. Willard, the nineteenth century temperance crusader. I asked the Yarnalls about her, and Mrs. Yarnall, sensing my opposition, said very sweetly and apologetically, "You see, Chris, in those days the whisky in this country was very bad quality."

June 11. Mrs. Rich had a long talk with me about her children. She feels she hasn't been a good mother to them. What should she do? Told her to be a good mother.

June 28. Wystan is staying at Caroline Newton's house at Daylesford. Today he gave a poetry reading to a large party of rich women. Nobody understood a single word; but they were very impressed. Wystan's untidiness and brusqueness impress them. He is never untidier than when he is wearing his best suit. He read in a loud bored indistinct voice, repeatedly looking ahead to see how much further he had to go.

1943

1943

August 18. Last night, because I was bored, I found myself doing what I would least have expected — hunting up Tennessee Williams. I located him, after some search, at a very squalid rooming house called The Palisades, at the other end of town — sitting typing a film story in a yachting cap, amidst a litter of dirty coffee cups, crumpled bed linen, and old newspapers. He seemed not in the least surprised to see me. In fact, his manner was that of the meditative sage to whose humble cabin the world-weary wanderer finally returns. He took it, with discreetly concealed amusement, as the most natural thing in the world that I should be having myself a holiday from the monastery. We had supper together on the pier, and I drank quite a lot of beer and talked sex the entire evening. Tennessee is the most relaxed creature imaginable: he works till he's tired, eats when he feels like it, sleeps when he feels inclined. The autoglide has long since broken down, so Tennessee has stopped paying for it, and the dealer is suing him, and he doesn't give a damn. He also has a fight on with Metro. He probably won't stay here long.

1959

April 8. Grey all day yesterday. Grey again this morning. Dangerous idling weather. Last night we had supper with Jo and Ben, and they showed their slides of our Mexican trip. I wanted to see them, to recapture some of the Mexican atmosphere, for my novel. What chiefly struck me: the dark blueness of the sky, the extraordinarily strong light of the setting or rising sun striking upward at the undersides of palm trees and making their fronds flash with a metallic sheen, like swords. The bandstands — some of them imported from France, perhaps: fancy lace ironwork, supported by naked girls. The disproportionate size of the great twin-towered baroque churches. The utter absence of any sort of landscape gardening: buildings arise and stand up unapologetically in the midst of dumps and barren lots. I absolutely, absolutely must get on with the novel. Just add page to page, without too much considering, until I have a first draft — no matter how short, how crude.

May 11. Heinz has written, suggesting that I sponsor the immigration of Gerda, Christian, and himself to the States, and that we shall all then live together in a house that I'm to buy. He offers, of course, to pay all this money back by degrees. And now I must answer his letter — explaining tactfully that this scheme is impossible; that is, I'd rather die than agree to it.

You can purchase the diaries of Christopher Isherwood here.

"When Did You Leave Heaven (demo)" - Bob Dylan (mp3)

"Just When I Needed You Most (demo)" - Bob Dylan (mp3)

"Freedom for the Stallion (demo)" - Bob Dylan (mp3)

BOOKS

BOOKS  Friday, January 22, 2016 at 2:44PM

Friday, January 22, 2016 at 2:44PM

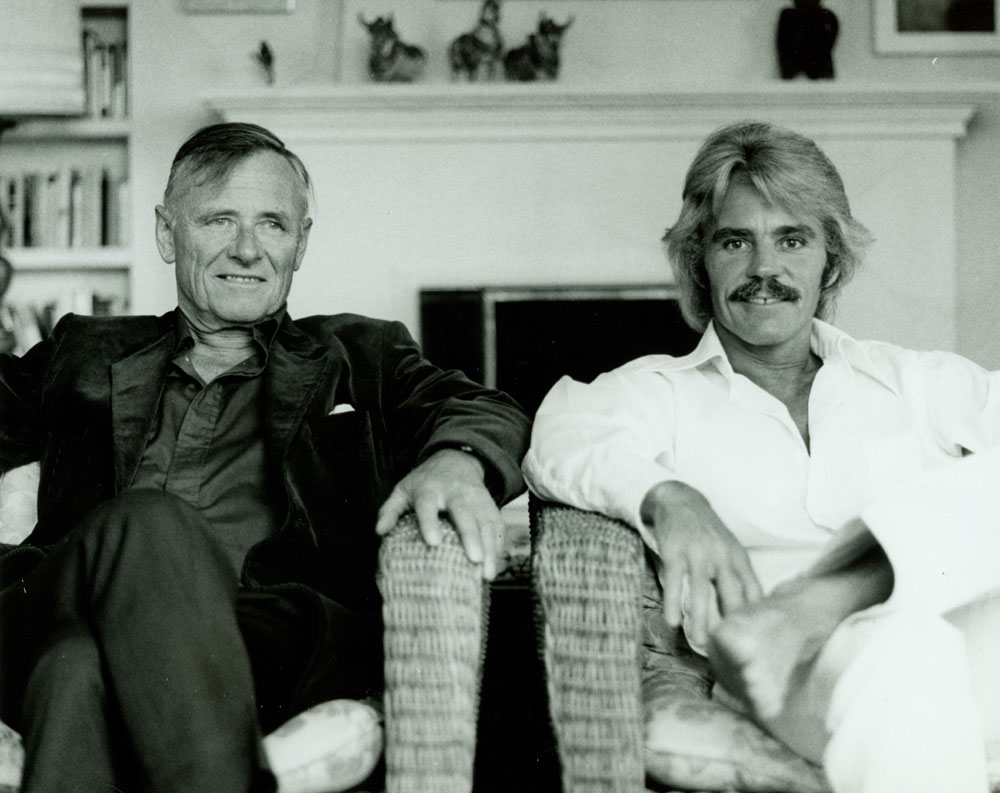

with D.H. Lawrence

with D.H. Lawrence

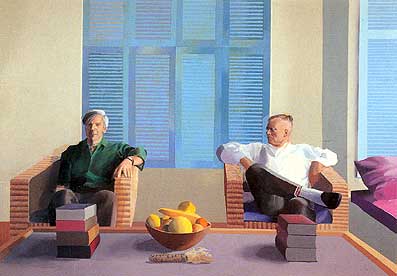

aldous huxley,

aldous huxley,  alex carnevale

alex carnevale