POETRY

POETRY « In Which We Experience The Jumping Catfish Love of Anne Sexton »

Sunday, July 25, 2010 at 11:38AM

Sunday, July 25, 2010 at 11:38AM

Anne to the Hilt

by ALEX CARNEVALE

The great theme is not Romeo and Juliet. The great theme we all share is that of becoming ourselves, of overcoming our father and mother, of assuming our identities somehow.

— from Anne Sexton's early introduction to The Double Image

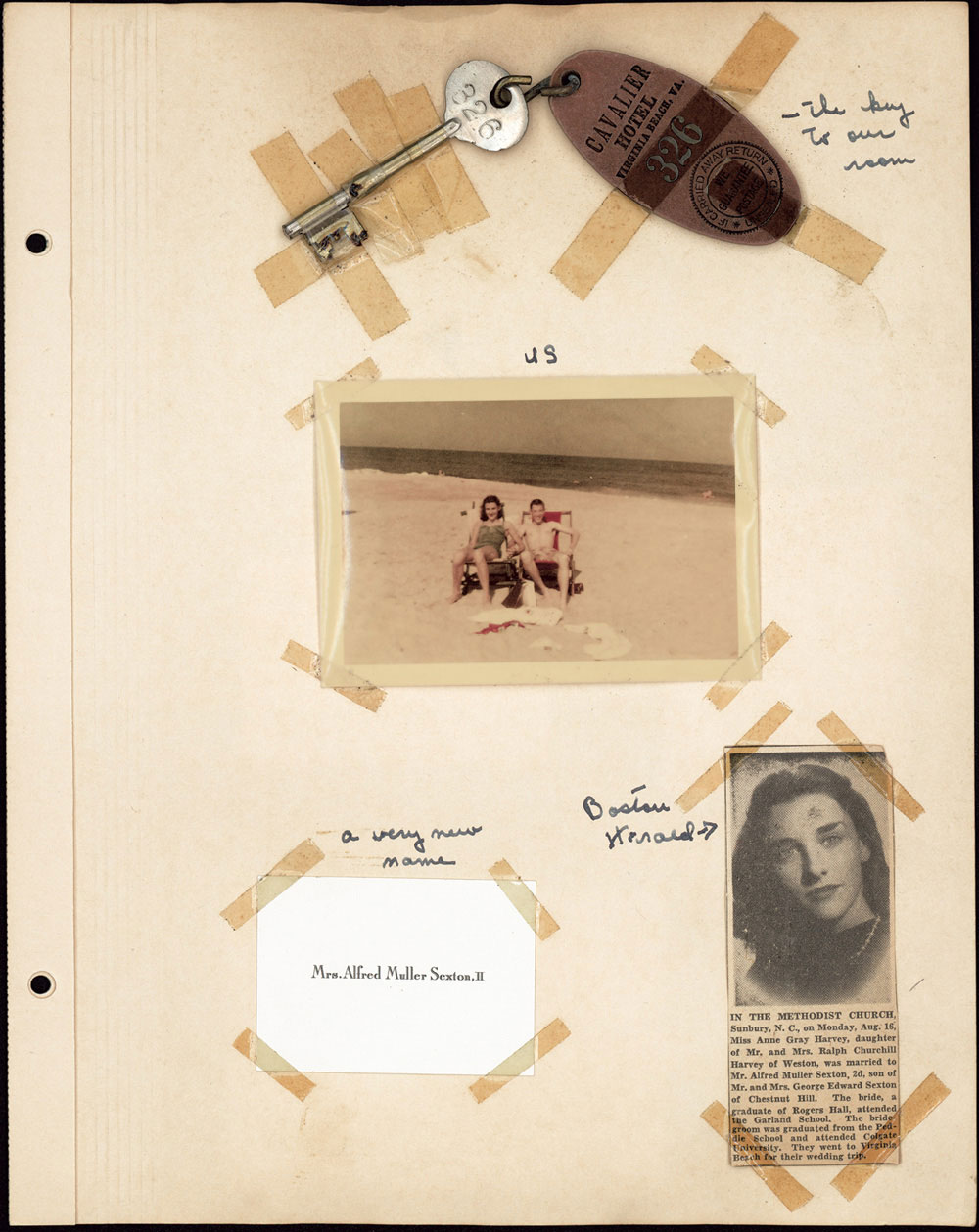

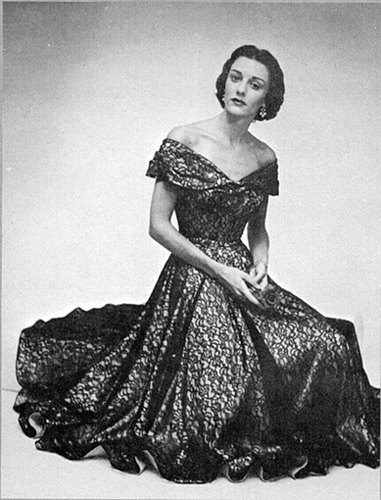

Anne Gray Harvey didn't start writing poetry until she was 28. Before then she was a model with Boston's Hart Agency. In 1948, at the age of 20, Anne ran off and eloped with Kayo Sexton. After she'd married Kayo, they sent along the same telegram to each of their parents. The Sextons tosses theirs away in a fury at the union, although they would later grow closer to Anne than her own parents. Anne's parents preserved the telegram for posterity:

Living off Kayo's parents and then with her husband supporting her, Anne began to pursue her poetry, taking her first class with the mercurial poet John Holmes. Her complicated relationship with Holmes' aesthetic was later superceded by Robert Lowell. By the time she met Lowell, she had already made her first suicide attempt. She wrote this letter to get into Lowell's class at Boston University.

September 15th, 1958

Dear Mr. Lowell:

What a fine letter you wrote me. I am considering framing it to prove to all comers that poets are people. I am so pleased that you think my work shows promise, that I shall need no new proof for possibly a month.

Since receiving your letter I have been busy begging money from old fat relatives. Today, with 90 dollars in my fist, I called the registrar's office. However, it seems they are not bouncing with joy at the thought of "special students" with no particular degree. A Mr. Wilder said I would have to wait until after registration and see if there were too many students in the class. I forward this information to you because I gather he will present you with the problem.

I hasten to add, since he may forget my name, that I am one of the vagrant applications that awaits your decision. He asked me if I were connected with any publication. I am not. In fact, I am totally disconnected from everything. I did not mention my slim list of credits, thinking he might wonder WHAT I was talking about. I am supposed to call him on Friday morning at eleven.

If this doesn't pan out I can always try for the second semester. I am even tempted to sit watching your lovely letters of praise and forget all about the work and criticism and growth that I would enjoy working with you.

I am more than a little shy of the great factories of humanity, like B.U., and it will take considerable moral courage to get on with this complicated application, registration, and these new hurdles. Somewhere, I hope I will get to a classroom where Robert Lowell is talking about poetry. I don't want the three credits, I am not sweetened with a background of knowledge, am even defensive saying ("I don't know anything.") — but if you can squeeze me in, I will be there.

You do not need to answer this letter. I just wanted to let you know the meanwhiles and if so's. If I do not make it I will surely meet you sometime.

Yours sincerely,

Anne Sexton

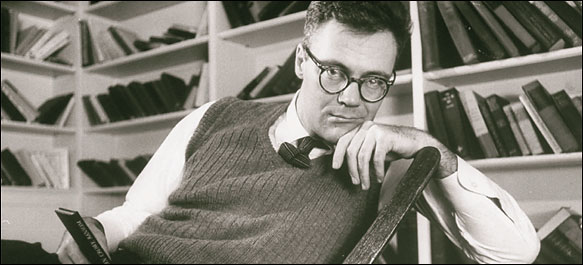

bob lowellAnne had a complicated relationship with her parents, but they were as much raw material for her existing troubles as the source of them. Whatever happened with her and her father (he got rich selling various goods during World War II), Anne was predisposed to mental illness from the first, and spent most of her life on medication (specifically the antipsychotic thorazine) and under analysis. Her manic qualities are obvious from her letters, which represent an extraordinary output of energy. Anne's writing began as a way of coping with her illness, and her letter writing was the best kind of therapy. Her relationships with poets like Maxine Kumin and W.D. Snodgrass are preserved in this form.

bob lowellAnne had a complicated relationship with her parents, but they were as much raw material for her existing troubles as the source of them. Whatever happened with her and her father (he got rich selling various goods during World War II), Anne was predisposed to mental illness from the first, and spent most of her life on medication (specifically the antipsychotic thorazine) and under analysis. Her manic qualities are obvious from her letters, which represent an extraordinary output of energy. Anne's writing began as a way of coping with her illness, and her letter writing was the best kind of therapy. Her relationships with poets like Maxine Kumin and W.D. Snodgrass are preserved in this form.

November 28, 1958

To W.D. Snodgrass

Dear passionflower tender,

I was just looking out the window at the truck that was delivering two bottles of whiskey and it was, yes it was, snowing. I am young. I am younger each year at the first snow. When I see it, suddenly, in the air, all little and white and moving; then I am in love again and very young and I believe everything. Christ is in his manger and Santa in heaven.

I am a good girl and the man left two bottles of booze because my mother is rich and she ordered them. She is staying with us because my father is ill, in the hospital with a stroke. My mother keeps telling me that soon I will be rich because they will be dead (she is greedily wordy about this) and I listen to her and think about a poem by you about a mother...she is like a star...everything MUST center around her.

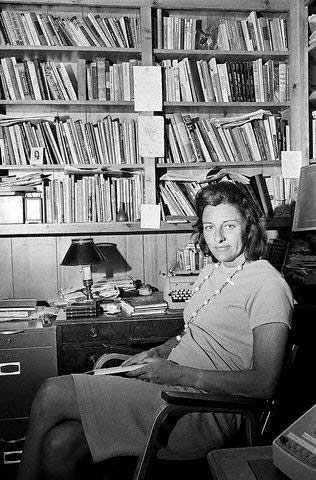

anne's self-portrait

anne's self-portrait

And I write in a hurry because it is snowing and because this morning I received a letter from you and I because I would rather write to you this moment than sleep with Apollo or even go outside and measure the snow on the walk. I write to you because you understand my letters and do not take them TOO seriously or too casually. And because, after all, I love you and you are my best god anyhow.

Did I? Why do I forget everything! send you a complete copy of my "Double Image" poem the other day? I sent it someone that I cared about. But was it you? Who else could there be, that I care about - about reading it??? I think I did. If so — read it. If not — let me know.

I also received a nice letter from Jim McConk taking two poems for Epoch (it's about time) and saying such nice things about my work and when was my book coming out (I didn't believe that, but it looked nice on the page) and all. That sweet ladypoet from Rochester took two poems for Voices (don't know why I sent there — but did —) one of the ones was a new one, "Obsessional Combination of Ontological Inscape, Trickery and Love" ... why am I rambling on? Now I know why I am really writing you so promptly. I have a question—

How do I go about applying for Yaddo? Would John Holmes be enough of a recommendation? Who else could I find? Would Nolan Miller (he thinks he discovered me) help? Or Hollis Summers (he writes me letters) — I might be able to go. I think the first thing to do is see if I could get in — do you think, perhaps, it would be better to wait a year (in view of that fact that I'm such a "new" writer)...

John Holmes is having a small party for John C. Ransom next Wed. night and has asked me so maybe I will meet someone who will decide to discover me. I will be on the lookout for a possible famous soul who can recommend me.

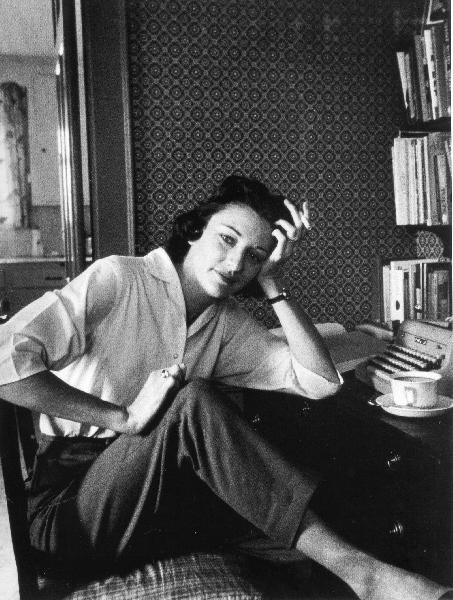

skinny dipping in Newton 1962

skinny dipping in Newton 1962

But how do you go about it, dear night clerk; the future is my own. I am trying to steer. I paddle my own craft with toothpick oars. Thank you for quoting my letter. I will write you dozens more someday. I doubt if I can use it in a poem (but there is lots more where that came from). I am a romantic and am full of tiers of tries of all that.

let me know about Yaddo —

yours Anne

Success came quickly, and while the accompanying confidence kept her going through her constant bouts of anxiety and depression, it also exaggerated her considerable alienation. At times she could be deft about how she pushed herself on other people, but she was often extremely intrusive, even on the lives of her own husband and daughters. Her boundaries weren't too spectacular.

Anne's best book, her 1962 collection All My Pretty Ones, was roundly celebrated. It was even nominated for the National Book Award, the second time Anne would receive that accolade. The one exception was a negative review by James Dickey that appeared in The New York Times Book Review. Anne carried the clipping around in her wallet:

It would be hard to find a writer who dwells more insistently on the pathetic and disgusting aspects of bodily experience as though this made the writing more real, it would also be difficult to find a more hopelessly mechanical approach to reporting these matters than the one she employs... Her recourse to the studiedly off-hand diction favored by Randall Jarrell and Elizabeth Bishop and her habitual gravitation to the domestic and the "anti-poetic" seem to me as contrived as any poet's harking after galleons and sunsets and forbidden pleasures.

Anne was fairly good with criticism; in fact it is rumored she was the last person to take criticism well in this country. After reading the review, she wrote Dickey a letter and befriended him. In short order he was eating out of her hand. She did this with most of her antagonists, the mark of every disturbed disposition.

one of anne's early effortsAnne's letters also show why she was renowned as a capable, albeit wildly erratic, teacher. She did feature, as all great instructors do, the exact right combination of total self-involvement and magnetic empathy that drew students to her in the classroom. She had an astonishing amount of attention to give, and as a poet she was as engaged with her critics (of which there were many) as her admirers. She was so manic in the way that she interacted with people that were if not for the relative stability of her husband, she might have gone completely off the rails.

one of anne's early effortsAnne's letters also show why she was renowned as a capable, albeit wildly erratic, teacher. She did feature, as all great instructors do, the exact right combination of total self-involvement and magnetic empathy that drew students to her in the classroom. She had an astonishing amount of attention to give, and as a poet she was as engaged with her critics (of which there were many) as her admirers. She was so manic in the way that she interacted with people that were if not for the relative stability of her husband, she might have gone completely off the rails.

The quintessential volume of Anne's letters is Anne Sexton: A Self Portrait in Letters, edited by two women who knew Sexton intimately, Lois Ames and Anne's daughter Linda. Anne's number one correspondent was her husband, especially when she was separated from him. In one letter, Anne quotes John Ciardi's phrase that "a woman marries what she needs." The following letter to her husband Kayo is perhaps proof of this. Anne was on a long European trip that had started when she and her travelling companion had all their possessions stolen. The flood of ensuing letters were wild beacons across the Atlantic.

Sept 7th, 1963

Dearest Kayo,

I want, though not often, to write you a letter of your own...i.e. a love letter. It can be a drag to have to speak publicy (to all, the girls and whoever, sometimes I feel to the whole neighborhood) ...when I often long for you and wish to speak only to you. Naturally the news goes on, the road moves, the travelerama continues and with it, with each time I type, are these almost unspoken words of love for you. Kayo, my darling, I miss you terribly. Each food I taste that I think worthy of your taste I miss you more. And more! Oh, Boots, there are times, despite the excitement of the buildings, of the food, of the people, when longing for you wells up in me... and I want to be home beside you in the bed looking at t.v. or at the kitchen table drinking a martini...(for God's sake now Sandy is talking and talking and all day she has been silent but when I start to write, well then she talks...) enough complaints. Actually we get along pretty well, except for a fight last night that didn't last long. I was typing out the list for Kazan and asking her how to spell and she sounded irritated and I barked back and told her to go to hell, etc. She went out of the room in huff and went to the john and smoked a cig. Good for me I sez...might as well speak up and clean the slate off once in awhile.

I want, though not often, to write you a letter of your own...i.e. a love letter. It can be a drag to have to speak publicy (to all, the girls and whoever, sometimes I feel to the whole neighborhood) ...when I often long for you and wish to speak only to you. Naturally the news goes on, the road moves, the travelerama continues and with it, with each time I type, are these almost unspoken words of love for you. Kayo, my darling, I miss you terribly. Each food I taste that I think worthy of your taste I miss you more. And more! Oh, Boots, there are times, despite the excitement of the buildings, of the food, of the people, when longing for you wells up in me... and I want to be home beside you in the bed looking at t.v. or at the kitchen table drinking a martini...(for God's sake now Sandy is talking and talking and all day she has been silent but when I start to write, well then she talks...) enough complaints. Actually we get along pretty well, except for a fight last night that didn't last long. I was typing out the list for Kazan and asking her how to spell and she sounded irritated and I barked back and told her to go to hell, etc. She went out of the room in huff and went to the john and smoked a cig. Good for me I sez...might as well speak up and clean the slate off once in awhile.

Kayo, the night before last I dreamt you were having an affair with someone and I woke up crying! Awful. Please keep loving me! I love you so much and feel you are here with me all the time...miss you more than I had thought possible. True, I am terribly busy what with losing everything! And all. The shock of losing it all just doesn't sink in. I lost all the books! Even nana's letter from Europe and grandfather's too.

with kayo in spring of 1968I did value and love those two books...but they are in the thief's wastebasket I guess...and life must go on not backward (just this fact makes me feel better, the trouble with therapy is that it makes life go backwards) and I am so tired of that old suffering. I want life to go forward even if I have to lose all my books and clothes to keep it going in that direction. And in a way, life is flowing toward us...you and me...and the life we have, for each day that goes by brings us nearer and each mile does it too.

with kayo in spring of 1968I did value and love those two books...but they are in the thief's wastebasket I guess...and life must go on not backward (just this fact makes me feel better, the trouble with therapy is that it makes life go backwards) and I am so tired of that old suffering. I want life to go forward even if I have to lose all my books and clothes to keep it going in that direction. And in a way, life is flowing toward us...you and me...and the life we have, for each day that goes by brings us nearer and each mile does it too.

in capri 1962I feel, sometimes, as if I were actually driving upon the map in our kitchen! I know I am here and you are there and yet, and yet, not quite. The sound of the ocean reminds me of the night in front of the house we rented on the Cape. (Do you remember that night on the beach?)

in capri 1962I feel, sometimes, as if I were actually driving upon the map in our kitchen! I know I am here and you are there and yet, and yet, not quite. The sound of the ocean reminds me of the night in front of the house we rented on the Cape. (Do you remember that night on the beach?)

I keep missing baked beans. Do you think you might send me a care package of baked beans? It is the first meal I think of and long for. Tonight in Knokke at our hotel (meals with room...a nice summer out of season hotel ... typical dutch bourgeois resort, very nice) we had tiny, two or three inch, lobster as a start and then steak and marvelous sauce and french fries. The french fries all over Europe are wonderful. I have become a lover of french fries (not frozen, not HoJo)...

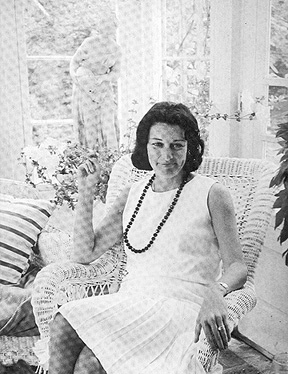

with maxine kuminBut you know, Kayo, I always did I have a "wanderlust" and it wasn't JUST A NEUROTIC wish to flee responsibility...but to see new things. And I do love that. I don't have the time or energy to get depressed or anxious. If I get anxious I seem to have four miles of walking in front of me and that takes care of THAT. Tonight we are supposed to be at the Poetry Festival Ball (for which I bought that damn expensive new dress in Brussels) but which I don't feel like going to. The sea has undone me. To hell with the ball. The dress I will wear on New Year's Eve and you will fall in love with me. That's what I want the dress for.

with maxine kuminBut you know, Kayo, I always did I have a "wanderlust" and it wasn't JUST A NEUROTIC wish to flee responsibility...but to see new things. And I do love that. I don't have the time or energy to get depressed or anxious. If I get anxious I seem to have four miles of walking in front of me and that takes care of THAT. Tonight we are supposed to be at the Poetry Festival Ball (for which I bought that damn expensive new dress in Brussels) but which I don't feel like going to. The sea has undone me. To hell with the ball. The dress I will wear on New Year's Eve and you will fall in love with me. That's what I want the dress for.

Meanwhile, I'll wear the few rags I have left. We have a copy of what we sent to Kazan as a list and will send it later, perhaps from Amsterdam (right now using mailers) for you to check. I wrote it out quite correctly, be sure to check with him and see what's up and tell him clothes all new from trip and not to devalue them as "used" ... some never worn. Kayo, my boots, keep loving me. It is hard to go so long without letters from you. Every night before sleep I read the ones I got in Paris but then you had never heard from me...the time lapse is painful (that's why the cable). You hear from us more regularly, but it is hard to wait this long, I become fearful and afraid, afraid I'll lose you. I know that IS silly, but there it is, and in all its little ugly unsureness and with its open love. Europe is fascinating. I am truly interested and excited but I miss you very much and love you with all my heart. Usually I must write the large common letter. But tonight I must say my special say which goes for always but must be said once more. I love you.

Anne

Later in the month, she sent the following telegram:

VENICE IMPOSSIBLY BEAUTIFUL YOUR LETTERS BETTER THAN WINE STAYING 8 DAYS PLEASE WRITE HERE JUMPING CATFISH LOVE

To me, Anne seems the living embodiment of something that is in all of us; in Anne it was the entire thing. She could not live, was not able to survive, without chronicling her life, without remedying the errors she had met and explaining them, often to large audiences, in order to set them right. She is a reminder that while we can change, a part of us never does.

anne's report card

anne's report card

As she got older and struggled more with her illness, alcoholism too began to take hold. Her breakdowns had led to several hospitalizations, but her writing continued. She distanced herself from many of her oldest friends, and her letters become evidence of a closer relationship with fans who randomly connected to her poems than those who knew her best. Her clipped bursts of enthusiasms toward her admirers are both sweet and chilling at the same time. Anne received a letter from Dorianne Goetz, who wrote her from a mental hospital, and sent back this postcard in June of 1965:

in her study, spring 1966Dear Doris

in her study, spring 1966Dear Doris

Thank you so much for your note. I'm so pleased you like my work. I hope you can get a chance to see the new poem out in Harper's this month (June) called "For the Year of the Insane." It is only for a few people.

I would like it if you could be one of them.

I wish I were nineteen. Not that it's better or worse to be me at 36 but it gives you so much more time to grow. Inside I'm only thirteen and outside I have wrinkles and a family and many who depend on me. How silly all this is when you are actually 13. That's what I mean "I wish." Time to grow — it's so needed. Hope you still find Hillside "a wonderful place." I've been in so many that aren't. But that's another story...Please send poems. I'd like to see them —

Best —

Anne Sexton

Before filing for divorce from Kayo, she accompanied him on a safari to Africa, one of his long-term goals. She was really grossed out by the bloodshed as a lifelong vegetarian but suffered through it for him.

Anne killed herself on October 4, 1974 after a day of lunch with Maxine Kumin and time spent proofing her new book. In 1969 a letter to her daughter Linda, who would become her literary executor, anticipated her death:

Dear Linda,

I am in the middle of a flight to St. Louis to give a reading. I was reading a New Yorker story that made me think of my mother all alone in the seat I whispered to her "I know, Mother, I know." (Found a pen!) And I thought of you — someday flying somewhere all alone and me dead perhaps and you wishing to speak to me.

in front of their weston home with linda, 1966And I want to speak back. (Linda, maybe it won't be flying, maybe it will be at your own kitchen table drinking tea some afternoon when you are 40. Anytime.) - I want to say back.

in front of their weston home with linda, 1966And I want to speak back. (Linda, maybe it won't be flying, maybe it will be at your own kitchen table drinking tea some afternoon when you are 40. Anytime.) - I want to say back.

1st I love you

2. You never let me down

3. I know. I was there once. I too, was 40 with a dead mother who I needed still.

This is my message to the 40-year-old Linda. No matter what happens you were always my bobolink, my special Linda Gray. Life is not easy. It is awfully lonely. I know that. Now you too know it — wherever you are, Linda, talking to me. But I've had a good life — I wrote unhappy — but I lived to the hilt. You too, Linda, Live to the HILT! To the top. I love you, 40-year old Linda, and I love what you do, what you find, what you are! Be your own woman. Belong to those you love. Talk to my poems, and talk to your heart — I'm in both: if you need me. I lied, Linda. I did love my mother and she loved me. She never held me but I miss her, so that I have to deny I ever loved her - or she me! Silly Anne! So there.

XOXOXO

Mom

Alex Carnevale is the editor of This Recording. He tumbls here and twitters here.

To Beat Death Down With A Stick, To Take Over

an interview with Anne Sexton and Maxine Kumin

by ELAINE SHOWALTER

Kumin: Meeting Anne was really fantastic. When I met Annie she was a little flower child, she was the ex-fashion model. She wore very spiky high heels.

Sexton: Well, that was the age.

Kumin: Yes, it was. Well, she was totally chic, and I was sort of more frumpy.

Sexton: You were the most frump of the frumps. You had your little hair in a bun.

Kumin: I was the chief frump. She was really chic and she wore flowers in her hair.

Showalter: Where did you model? I remember reading that, and then it dropped out of your blurbs.

Sexton: It's called the Hart Agency, in Boston.

Kumin: She was a Hart girl. At any rate, we met at the Boston Center for Adult Education where we had each come to study with John Holmes.

Sexton: I came trembling, thinking, oh dear god, with the most ghastly poems. Oh god, were they bad!

Kumin: Well...I don't know if that's true.

Sexton: Oh, oh, Maxine, horrible, horrible. Anyway, your impression of me was — ?'

Kumin: And my impression of Anne was — I don't know what my impression was. I was very taken with her. I think we were each very taken with each other.

Sexton: Now wait a minute. You were scared of me.

Kumin: I was terrified of her, I had just had my closest friend commit suicide, in a postpartum depression. Gassed herself.

Sexton: I wasn't writing about that right off.

Kumin: Now, wait a minute. I'm just saying why I was scared.

Sexton: Why should you know I had anything to do with it?

Kumin: Well, I knew your history.

Sexton: How?

Kumin: You were very open about the fact, of why you had begun to write poetry. You had just gotten out of the mental hospital. And something in me very much wanted to turn aside from this. I didn't want to let myself in for that again, for that separation. And Anne is still very much more flamboyant and open a person than I am. I'm much more closed up, restrained. I think this is certain, although much less so now than then.

Sexton: Can I say? Since your analysis — you're quite a changed person.

Kumin: Yes, since my analysis.

Sexton: I mean, she's gotten attractive and yummy. Before her hair was pulled back and in a bun—

Showalter: I wouldn't have recognized you, Maxine, from your pictures.

Sexton: No pictures are good. She was attractive then, she was attractive then, just a bad picture.

Kumin: The picture on the novel coming out next year is a really good picture of me and my dog. I recommend that picture.

Sexton: She keeps saying, look at my dog. As if the dog were more important.

Kumin: He is kind of spectacular. Anyway, Anne and I met, and we drove into this class together. For a long time, she used to pick me up and —

Sexton: Not at the beginning you didn't. I can remember, it was funny. I remember you going to a reading at Wellesley College and you picking me up. I had on sandals. You said look, she has prehensile toes. I've never forgotten it. And I said, look, anytime you want me to go to reading or anything (because I was desperate then) I'll do anything. And I started to drive Maxine to the Adult Center.

Kumin: And from that we began to go to all sorts of readings together. Actually the reading at Wellesley College was Marianne Moore.

Sexton: Remember her? Because she kept contradicting and saying, now don't handle a line this way, don't do that, that's very bad, you know, and don't end-stop here.

Kumin: She mumbled so. She read so badly. She was a character, in her tricorner hat and her great black robe.

marianne moore & ali

marianne moore & ali

Sexton: Do you remember going to hear Robert Graves? Dear god, he was ghastly!

Kumin: Now, look, we are not here to tell about people who were ghastly readers or we'll be here all night.

Showalter: Was John Holmes in charge of that workshop?

Kumin: Yes, John Holmes was teaching a little workshop, for anybody. It was available to the world, whoever wanted to come. And we would all try our poems. And this, I think, is how Anne and I learned to work by hearing a poem, because we didn't bring copies. John would sit at the head of the table and shuffle through the poems.

Sexton: He didn't do anything alphabetically.

Kumin: And we would all sit there dying, hoping to be chosen.

Sexton: Oh, you'd pray to be chosen.

Showalter: Not afraid to have a poem read?

Sexton: No, not afraid, wanting to be chosen.

Kumin: And he would read your poem, and the class would then discuss it.

Sexton: And he would.

Kumin: And he would.

Sexton: Now we have to go into the fact that as it grew later — well, we used to go out afterwards. John didn't drink.

Kumin: John was a former alcoholic.

Sexton: I don't think I drank myself. I don't think I drank much then, really. I had a beer.

Kumin: But he was really on the wagon. He had been a severe alcoholic. And then after that we broke off from the Boston Center and we formed our own group.

Sexton: But I didn't.

Kumin: You certainly did. When we broke off?

Sexton: I was seeing Robert Lowell.

Kumin: No, that was much later. That was after John was dead.

Sexton: No, wait a minute. I'm very sorry. I was going to Robert Lowell's class, and still John's, without you. Begging for the approval that Daddy would never give. Why was I so masochistic?

Showalter: Was John Holmes a difficult person for a woman to work with?

Sexton: John Holmes didn't approve of a thing about me. He hated my poetry. I remember, even after Maxine had left, and I was still with Holmes, there was a new girl who came in. And he ketp saying, oh, let us see new poems, new poems. We need them. And here I was giving him things that were later anthologized forever. I mean, really good poems.

I remember one night Sam Albert and me going to John's. It was sleeting out, but we make it. And he's on his way out and he's so happy we were going out. I think maybe that moment he forgave me a little.

Kumin: I was then teaching at Tufts, but we all read at Tufts, in the David Steinman series.

Sexton: I never did. No, he wasn't going to ask me.

Kumin: We used to go to parties at John's after all those readings—after John Crowe Ransom, and after Robert Frost. Frost said, don't sit there mumbling in the shadows, come up here closer. By then he was very deaf. And I was so awed.

Showalter: Is the poetry workshopping diminishing too? Do you do this less, need this less, than you used to?

Sexton: No, not as long as we're writing.

Kumin: I think the difference is that perhaps this year haven't been writing as much.

Sexton: I haven't been writing as much either; I've been having an upsetting time.

Kumin: I think the intensity is the same, but the frequency has changed.

Sexton: But just the other day Maxine said, well, that's a therapeutic poem, and I said, for god's sake, forget that. I want to make it a real poem. Then I forced her into helping me make it a real poem, instead of just a kind of therapy for myself. But I remember once a long time ago a poem called "Cripples and Other Stories." I showed it to my psychoanalyst—it was half done—and I threw it in the wastebasket. Very unusual because I usually put them away forever. But this was in the wastebasket. I said, would you by any chance be interested in hat's in the wastebasket? And she said, wait a minute, Anne. You could make a real poem out of that. And you know how different that is from Maxine's voice.

Kumin: I happen to really love that poem.

Sexton: Really? I hate it. Although it's good. It reads well. But we're different temperatures, Maxine and I . I have to be warmer. We can't even be in the same room.

Kumin: I'm always taking my clothes off and Anne is putting on coats and sweaters.

I think that's we're always proud of ourselves that we're not dependent on the relationship. We're very autonomous people, but is a nurturing relationship.

Showalter: What difference would it have made if there had been a women's movement?

Kumin: We would have felt a lot less secretive.

Sexton: Yes, we would have felt legitimate.

Kumin: We both have repressed, kept out of the public eye that we did this.

Sexton: I mean, our husbands, we could have thrown it at them.

Showalter: Why did you feel so ashamed of this mutual support?

Sexton: We did. We were ashamed. We had to keep ourselves separate.

Kumin: We were both struggling for identity.

Sexton: My mother was very destructive. The only person who was very constructive in my life was my great-aunt, and of course she went mad when I was thirteen. IT was probably the trauma of my life that I never got over.

Showalter: How did she go mad?

Kumin: Read "Some Foreign Letters."

Sexton: That doesn't help. Do you know "The Hex"? "Anna Who Was Mad" in Folly? Notice the guilt in them. But the hex is a misnomer. I had tachycardia and I thought it was just psychological.

Showalter: Were you named for her?

Sexton: Yes, we were namesakes. We had songs we would sing together. She cuddled me. I was tall, but I tried to cuddle up. My mother never touched me in my life, except to examine me. So I had bad experiences. But I wondered with this that every summer there was Nana, and she would rub my back for hours. My mother said, women don't touch women like that. And I wondered why I didn't become a lesbian. I kissed a boy and Nana went mad. She called me a whore and everything else.

I think I'm dominating this interview.

Kumin: You are, Anne.

Showalter: Maxine, in The Passions of Uxport, you describe the death of a child from leukemia—a death which has haunted me ever since. Do you think it's more difficult for a woman to write about the death of a child?

Kumin: In all my novels there's a death. In The Abduction there's a sixteen-year-old who dies in a terrible car crash. Perhaps as a mother. I have a fear of a loss of a child.

Sexton: We all know that a child going is the worst suffering.

Kumin: Many years ago, my brother lost a child, and I remember this terrible Spartan funeral. That's the funeral in The Passions of Uxport, when he says the Hebrew prayer for the dead.

Sexton: Do you remember we were young and going to a place called the New England Poetry Club, the first year we won the prizes, first or second. We were terrified. It was our first reading. Maxine's voice was trembling, so we couldn't hear her.

Kumin: I couldn't breathe.

Sexton: I couldn't stand up. I was shaking so. I sat on the table.

Kumin: I wonder if there was a trembling in us—the wicked mother, or the wicked witch, or whatever those ladies were to us.

Showalter: They were all women?

Kumin: There were a few squashy old men.

Sexton: There were young men too. John was there. Sam was there.

Showalter: Did you have trouble with women writer of another generation? In Louise Bogan's Letters—she says about Anne? She doesn't seem to have been able to accept the subjects.

Kumin: This was the problem with a great many people. Women are not supposed to have uteruses, especially in poems.

Sexton: To me, there's nothing that can't be talked about in art. But I hate the way I'm anthologized in women's lib anthologies. They cull out the "hate men" poems, and leave nothing else. They show only one little aspect of me. Naturally there are times I hate men, who wouldn't? But there are times I love them. The feminists are doing themselves a disservice to show just this.

Kumin: They'll get over that.

Sexton: Yes, but by then, they won't be published. Therefore they've lost their chance.

Showalter: When I anthologized you in my book, Women's Liberation and Literature, I chose "Abortion," "Housewife," and "For My Lover on Returning To His Wife." And I like all those poems very much; I'd choose them again.

anne's scrapbook

anne's scrapbook

Sexton: "For My Lover" is a help. It doesn't cost very much money to get "Housewife" — you can get it cheap. A strange thing — "a woman is her mother." That's how it ends. A housecleaner—washing herself down, watching the house. It was about my mother-in-law.

Showalter: A woman is her mother-in-law.

1974

from anne's modeling portfolio

from anne's modeling portfolio

I am, each day,

typing out the God

my typewriter believes in.

Very quick. Very intense,

like a wolf at a live heart.

"Suburban War" - Arcade Fire (mp3)

"Wasted Hours" - Arcade Fire (mp3)

"The Suburbs" - Arcade Fire (mp3)

alex carnevale,

alex carnevale,  anne sexton,

anne sexton,  maxine kumin

maxine kumin

Reader Comments (2)

The woman sitting next to Anne Sexton in that picture does not look like Maxine Kumin to me, it looks like Tillie Olsen???

Very unique, rich and rare bibliography