NEW YORK

NEW YORK In Which Emily Gould Is Bored To Death With Brooklyn Cliches

Tuesday, October 6, 2009 at 12:22PM

Tuesday, October 6, 2009 at 12:22PM

No Sleep Till Brooklyn

by EMILY GOULD

"Crowds of men and women attired in the usual costumes! how curious you are to me! On the ferry-boats, the hundreds and hundreds that cross, returning home, are more curious to me than you suppose; And you that shall cross from shore to shore years hence, are more to me, and more in my meditations, than you might suppose," wrote Walt Whitman in 1900, of his fellow Brooklyn ferry passengers.

Time-travel-noise! It's 2009. And now here is how those who cross from shore to shore are typically limned:

"The people like organic food and bicycles. They compost. They fuss over their children. They don’t miss living in Manhattan. You get the idea." So NYTimes Moscow correspondent Clifford Levy wrote recently, in an article that purported to give Muscovites a primer on Brooklynites and vice versa. "Denizens of Brownstone Brooklyn like to pad around in plastic clogs," Levy also pointed out.

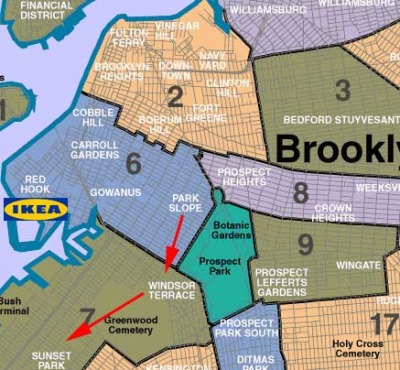

This kind of generalization is easy to come by, and so, to be honest, are Crocs, at least in Park Slope. That neighborhood and several others near or nearish to it -- Prospect Heights, Boerum Hill, Cobble Hill, Brooklyn Heights and Fort Greene -- are what Levy is referring to when he says "Brownstone Brooklyn." Levy is not referring to Bed-Stuy, though it is full of brownstones. Those brownstones don't count as brownstones, because they are not yet entirely occupied by white gentrifiers.

The trouble with dismissing the stereotypical people who lazy writers describe when they want to call up an emblematic image of Brooklyniness is that they exist. I see them all the time, glowy and unkempt, pushing their double stroller -- that odd kind where one child rides underneath, which seems un-fun for him-- and walking their large dog in the middle of the day on a weekday.

What do they do? How does it enable them to afford an $800 imported stroller? Why, during the pickup time for our Community Supported Agriculture vegetables, do they insist on letting little Phineas slowly, deliberately pluck his favorite 10 onions from the bin? "One... (an eternity passes)...two...(another eternity, this one longer)"... They apologize to me, in line behind them, and shoot me winsome smiles as they throw up their hands like "What are you going to do?" I have some suggestions, but I keep them to myself.

I try not to get too worked up, knowing that these people constitute but one skein -- well, maybe three or four skeins, and they're the most visible, they're some flashy kind of sparkle-thread -- in the incredibly diverse tapestry that makes up my neighborhood and my borough.

This, despite what pop culture would have you believe, but well, it's understandable that TV shows and movies and books and the New York Observer and New York magazine tend to fixate on either rich, overparenty breeders or rich, overstyled hipsters when writing about Brooklyn. The consumption habits and recreational activities and intellectual preoccupations of these groups are simply the easiest to mine for yuks.

It's hard to imagine Sarah Jessica Parker optioning an book about Borough Park Hasids, or Jonathan Ames developing an HBO series about a group of French-speaking African Baptists who stage lively revels in their Fort Greene church every Sunday.

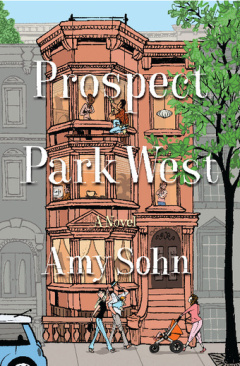

Instead, Parker has optioned Amy Sohn's recently-published novel Prospect Park West, which is a fantastical romp about the status anxieties of rich but not quite rich-enough Park Slope parents who vie for the attention of a secretly-troubled celebrity couple in their midst.

Ames' series is about a feckless Fort Greene writer who spots a Raymond Chandler paperback on the floor of his sunny brownstone apartment after Moishe's Movers finishes loading out the belongings of his erstwhile girlfriend and immediately decides to declare himself, via Craigslist, a private eye.

I watched the first episode of this series, Bored To Death -- a risky name for a show that, for people who aren't watching it for the thrill of spotting local landmarks, might be less than riveting -- at the end of a Brooklyn day. It was Yom Kippur and I had spent the morning at free services that are provided by an organization called "Brooklyn Jews." The services were held in Park Slope and I rode there from Clinton Hill on my bike.

Later I rode my bike to Brooklyn Heights for a break-the-fast meal of bagels and lox. As we wolfed the bagels and ate little mini-shortbreads from One Girl Cookies and looked out the beautiful bay window at the tall trees up and down the block shaking in a cloudburst, we talked about real estate, and the inexplicable dearth of good supermarkets in that neighborhood.

Afterwards I went to a bar in Fort Greene -- a German beer garden with no garden -- and, while waiting for my friends to arrive, chatted with an middle-aged man who was sipping a beer while his laundry spun in the dryer at the laundromat next door. He'd moved to the neighborhood -- actually, to an apartment above the beer garden -- from a Park Slope brownstone one year earlier. "It's a one bedroom about the size of this half of the bar, like, from there to there," he said, delimiting an arc with his pointing finger that encompassed a wide swath of bar-space. "$1350."

"FUCK you," I said. The man took this in the intended spirit, and chuckled and felt good about himself. It was the fourth time that day that someone had told me, unbidden, how much rent he paid.

Then I went home and watched Bored To Death. In the first episode the protagonist, "Jonathan Ames," who is Jason Schwartzman, has coffee with his friend Zack Galifianakis at Smooch. I guess the fictitious Jonathan Ames is unperturbed by the worst Yelp reviews I have ever seen for any business, and the flies. (To be fair, the veggie burger is great).

Jonathan and Zack have to sit outside because a postnatal yoga class has just gotten out and the shop is packed with mommies. A herd of their parked strollers clog the sidewalk outside; Jonathan trips over one as he gets up to leave.

I yawned. The ghost of Walt Whitman yawned. "Maybe less curious than I had supposed!" he mumbled. We shut off my computer and went to bed.

Emily Gould is a contributor to This Recording. She lives in Brooklyn and writes at Emily Magazine.

Massive Attack ft. Tunde Adebimpe - Pray for Rain (mp3)

Jay-Z ft. Alicia Keys - Empire State of Mind (mp3)

The Pains of Being Pure at Heart - Higher Than the Stars (mp3)

brooklyn,

brooklyn,  emily gould

emily gould