POETRY

POETRY In Which The Elements of Disbelief Are Very Strong In The Morning

Wednesday, December 29, 2010 at 10:37AM

Wednesday, December 29, 2010 at 10:37AM The following remembrances of Frank O'Hara appear in Homage to Frank O'Hara, edited by Joe LeSueur and Bill Berkson. You can purchase that volume here.

Memories of Frank

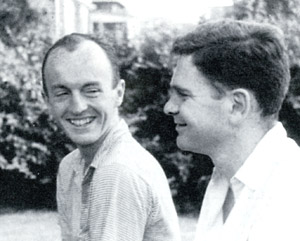

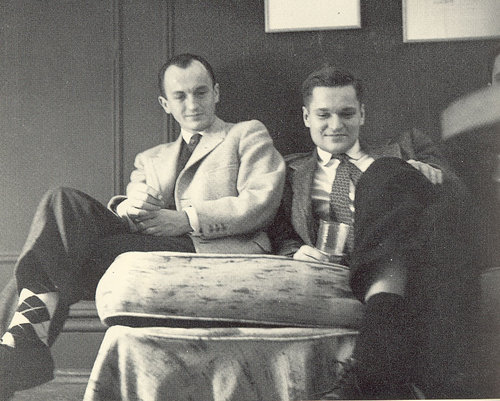

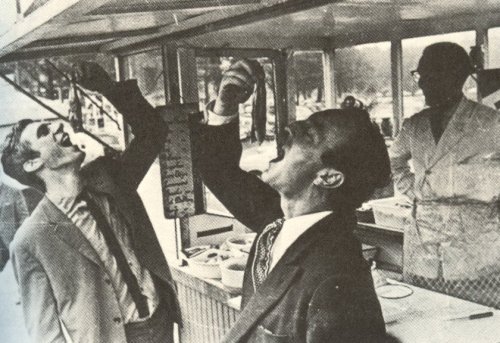

with grace hartigan Larry Rivers

with grace hartigan Larry Rivers

I began doing portraits of Frank in the fall of '52. That was after I'd slit my wrists over something. I phoned Frank, who happened to be in, and he came over and bandaged me up. Then we began seeing a lot more of each other and it was natural for me to use him as a model. Sex we got into later, when I'd already started drawing and painting him. There was always a dialogue going on during our working sessions. He gave me feedback and made me feel like what I was doing mattered, and after a while I found I needed him for my work. He was a great model. For one thing, he liked to model; he even felt complimented that you asked him to, and you ended up wanting him to like you. He had blazing blue eyes, so if you were stuck you could always put a little blue to make the work more interesting. His widow's peak gave you a place to anchor the picture, and his broken nose was dramatic and easy to get. At the time, I had no idea I was making so many pictures of him; I think I must have made a dozen portraits, and that's not counting drawings or paintings like "The Studio" and "Athlete's Dream" he appeared in. I always felt I was close to getting him but I never did, so I kept on trying.

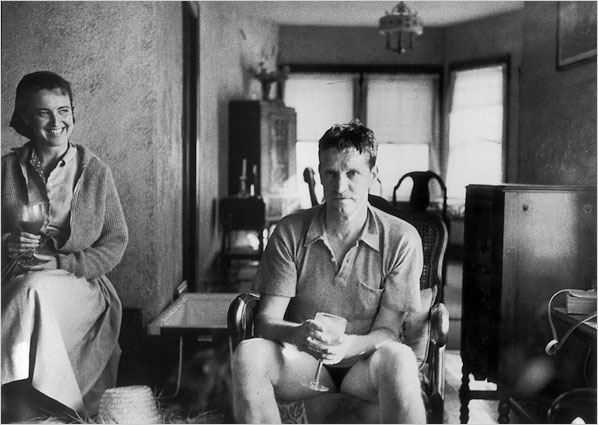

in front of larry rivers' house in southamptonTed Berrigan

in front of larry rivers' house in southamptonTed Berrigan

Frank O'Hara

Winter in the country, Southampton, pale horse

as the soot rises, then settles, over the pictures

The birds that were singing this morning have shut up

I thought I saw a couple, kissing, but Larry said no

It's a strange bird. He should know. & I think now

"Grandmother divided by monkey equals outer space." Ron

put me in that picture. In another picture, a good-

looking poet is thinking it over; nevertheless, he will

never speak of that it. But, his face is open, his eyes

are clear, and, leaning lightly on an elbow, fist below

his ear, he will never be less than perfectly frank,

listening, completely interested in whatever there may

be to hear. Attentive to me alone here. Between friends,

nothing would seem stranger to me than true intimacy.

What seems genuine, truly real, is thinking of you, how

that makes me feel. You are dead. And you'll never

write again about the country, that's true.

But the people in the sky really love

to have dinner & to talk a walk with you.

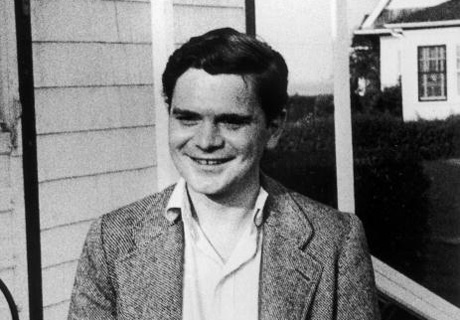

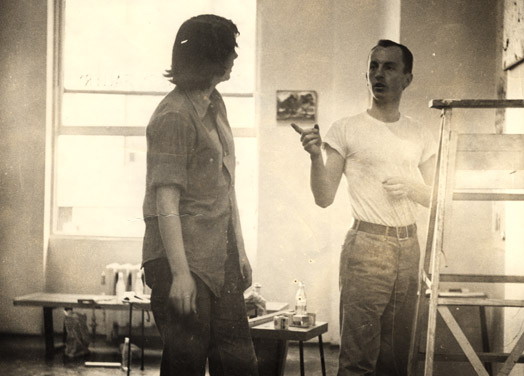

cambridge 1950 by jane freilicher Jane Freilicher

cambridge 1950 by jane freilicher Jane Freilicher

It is really a sketch painted from memory as he appeared characteristically in those days (1950, or 51) with his dark fuzzy shetland sweater, no shirt, chino pants & tennis shoes - Ivy League but rather exotic & chic in the N.Y. art world in those days. Frank was very well put together physically, the scale of his body, the delicate but irregular features of his face remind somewhat of the drawings of ideal male proportions by Dürer. He was so very pleasing to look at & I sometimes wonder if this attractiveness was one of the reasons so many painters enjoyed knowing him.

However, my painting was just an attempt to capture a fleeting sense of his physical presence as he seemed, often, to be standing in a doorway of a room, one arm bent up at the elbow, his weight poised on the balls of his feet, maybe saying something funny or charming, proffering a drink or listening attentively, alert & delightful.

Anne Waldman

April Dream

I'm with Frank O'Hara, Kenward Elmslie & Kenneth Koch visiting Donald Hall's studio or lab (live ivy league fraternity digs) in "Old Ann Arbor." Lots of drink and chit chat about latest long poems & how do we all rate with Shakespeare. Don is taking himself very seriously & nervously as grand host conducting us about the place. It's sort of a class reunion atmosphere, campus history (Harvard) & business to be discussed. German mugs, wooden knick knacks, prints, postcards decorate the room, Kenward making snappy cracks to me about every little detial. We notice huge panels of Frank O'Hara poems on several walls and Kenneth reads aloud: "a child means BONG" from Biotherm. We notice more panels with O'Hara works, white on red - very prettily shellacked - translated by Ted Berrigan. Slogan-like lines, "THERE'S NOBODY AT THE CONTROLS!" "NO MORE DYING." Frank is very modest about this and not altogether present (ghost). Then Don unveils a huge series of panels again printed on wood that's he's collecting for a huge anthology for which Frank O'Hara is writing the catalogue. Seems to be copies of Old Master, plus Cubists, Abstract Expressionists, Joe Brainards & George Schneeman nudes. Frank has already compiled the list or "key" but we're all supposed to guess what the "source" of each one is like a parlour game. The panels are hinged & like a scroll covered with soft copper which peels back.

I wonder what I am doing with this crowd of older men playing a guessing game. None of us are guessing properly the "sources," Kenneth the most agitated about this.

I wonder what I am doing with this crowd of older men playing a guessing game. None of us are guessing properly the "sources," Kenneth the most agitated about this.

Then the "key" is revealed and the first 2 on it are:

I. Du Boucheron

II. Jean du Jeanne Jeanne le (wine glass)

"I knew it! I knew it!" shouts Kenneth.

We are abruptly distracted from the game by children chorusing, "da da da du DA LA" over & over again, very guileless & sweet. We all go to a large bay window which looks over a gradeschool courtyard. Frank says, "Our youth."

April 17, 1977

with elaine de kooningTerry Southern

with elaine de kooningTerry Southern

Once I asked Larry Rivers about Frank's closest friends, who did he think was Frank's best friend, and so on.

"Oh my God," he said, "there were so many people who thought they were his best friend. I mean, he had this thing about making each person feel he was his best friend. I guess it was because he cared so much, about everybody."

Yes, I guess it was. Anyway, I know there are people who were better acquainted with Frank than I, but I'm certain there are none who enjoyed him more fully, think of him more often, or more fondly.

john ashbery’s photograph of frank o’hara, grace hartigan, allan kaprow, joe hazan, jane freilicher at george segal’s house in New Jersey, 1955

john ashbery’s photograph of frank o’hara, grace hartigan, allan kaprow, joe hazan, jane freilicher at george segal’s house in New Jersey, 1955

Barbara Guest

Frank and I happened to be in Paris at the same time in the summer of 1960. I was staying there with my family and had been very busy with the Guide Bleu looking at every placard on every building I could find. and I had located the"bateau lavoir" where Picasso and Max Jacob had first lived and where they had held all those studio parties with Apollinaire and Marie Laurencin. And across the street was a very good restaurant. I suggested that we have lunch there, our party included Grace Hartigan and her husband at the time, Robert Keene. We had a "marvelous" lunch, much wine and talk and we all congratulated ourselves on being in Paris and moreover being in Paris at the same time - a continuation of the Cedar St. Bar where we had formerly and consistently gathered. After lunch I suggested that we cross the street to the "bateau lavoir," a discovery of mine and one I thought would intrigue Frank. Not at all. He did go across the street, but he didn't bother to go into the building. "Barbara," he said, "that was their history and it doesn't interest me. What does interest me is ours, and we're making it now."

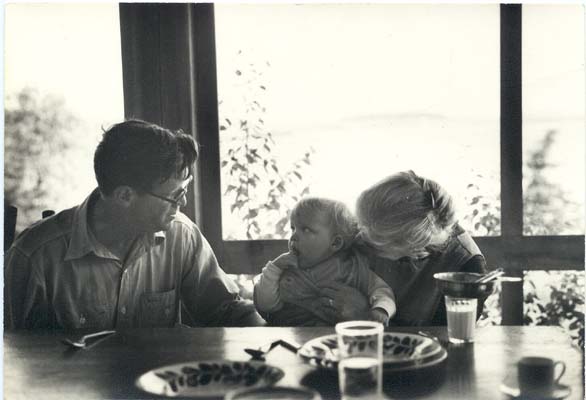

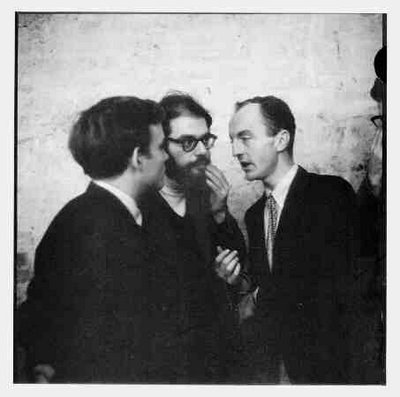

with allen ginsbergA Note on Frank O'Hara In The Early Fifties

with allen ginsbergA Note on Frank O'Hara In The Early Fifties

by KENNETH KOCH

The first thing of Frank O'Hara's I ever read was a story in the Harvard Advocate in 1948. It was about some people drunkenly going up stairs. During the next year, when I was living in New York, John Ashbery told me that Frank had started to write poems and that they were very good. I forget if I met Frank before or after John told me he had started writing poems. Actually, as I later found out, Frank had started writing poetry a long time before, and prose was only a temporary deviation for him.

In any case, the first time I read some of Frank's poems was in the summer of 1950, just before I left for France on a Fulbright grant. John Ashbery had mailed them to me and had described them enthusiastically. I didn't like them very much. I wrote back to John that Frank was not as good as we were, and then gave a few reasons why.

These poems by Frank were somehow packed in one of my suitcases when I went abroad, and I happened to read them again when I was in Aix-en-Provence. This time they seemed to me marvellous; I was very excited about them. Also very intimidated. I believe I liked them for the same reasons I had not liked them before - i.e. because they were sassy, colloquial, and full of realistic detail.

It was not till the summer of 1952 (after coming back from Europe, I had gone to California for a year) that I got to know Frank well. Know is not really the right word since it suggests something fairly calm and intellectual. This was something much more emotional and wild. Frank in his first two years in New York was having this kind of explosive effect on a lot of people that he met. Larry Rivers laters said that Frank had a way of making you feel you were terribly important and that this was very inspiring, which is true, but it was more than that.

His presence and his poetry made things go on around him which could not have happened in the same way if he hadn't been there. I know this is true of my poetry, and I would guess it was true also of the poetry of James Schuyler and John Ashbery, and of the painting of Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, Mike Goldberg, Grace Hartigan and other painters too.

One of the most startling things about Frank in the period when I first knew him was his ability to write a poem when other people were talking, or even to get up in the middle of a conversation, get his typewriter, and write a poem, sometimes participating in the conversation while doing so. This may sound affected when I describe it, but it wasn't so at all. The poems he wrote in this way were usually very good poems. I was electrified by his ability to do this at once tried to do it myself - (with considerably less success).

Frank and I collaborated on a birthday poem for Nina Castelli (summer 1952), a sestina. This was the first time I had written a poem with somebody else and also the first time I had been able to write a good sestina (my earlier attempts had always bogged down in mystery or symbolism). Artistic collaboration, like writing a poem in a crowded room, is something that seemed to be a natural part of Frank's talent. I put this in the past tense not because these things are not part of Frank's talent now, but for the sake of history - since I believe that, as far as American poetry is concerned, he started something.

Something about Frank that impressed me during the composition of the sestina was his feeling that the silliest idea actually in his head was better than the most profound idea in somebody's else head - which seems obvious once you know it, but how many poetrs have lived how many total years without finding it out?

This Nina Sestina collaboration occurred during one of the weekends in the summer of 1952 when Frank and I, Jane Freilicher, Larry Rivers, and various other writers and painters were in Easthampton. Jane and Frank were sporadically engaged in being in a movie which was being made out there by John Larouche.

Frank's most famous poem during the summer was "Hatred," a rather long poem which he had typed up on a very long piece of paper which had been part of a roll. Another of his works which burst on us all like bomb then was "Easter," a wonderful, energetic and rather obscene poem of four or five pages, which consisted mainly of a procession of various bodily parts and other objects across a vast landscape. It was like Lorca and Whitman in some ways, but very original.

I remember two things about it which were new: one was the phrase "the roses of Pennsylvania," and the other was the line in the middle of the poem which began "It is Easter!" (Easter, though it was the title, had not been mentioned before in the poem and apparently had nothing to do with it.) What I saw in these lines was 1) inspired irrelevance which turns out to be relevant (once Frank had said, "It is Easter!" the whole poem was obviously about death and resurrection); 2) the use of movie techniques in poetry (in this case coming down hard on the title in the middle of the work); 3) the detachment of beautiful words from traditional contexts and putting them in curious new American ones ("roses of Pennsylvania").

I remember two things about it which were new: one was the phrase "the roses of Pennsylvania," and the other was the line in the middle of the poem which began "It is Easter!" (Easter, though it was the title, had not been mentioned before in the poem and apparently had nothing to do with it.) What I saw in these lines was 1) inspired irrelevance which turns out to be relevant (once Frank had said, "It is Easter!" the whole poem was obviously about death and resurrection); 2) the use of movie techniques in poetry (in this case coming down hard on the title in the middle of the work); 3) the detachment of beautiful words from traditional contexts and putting them in curious new American ones ("roses of Pennsylvania").

He also mentioned a lot of things just because he liked them - for example, jujubes. Some of these things had not appeared before in poetry. His poetry contained aspirin tablets, Good Teeth buttons, and water pistols. His poems were full of passion and life; they weren't trivial because small things were called in them by name.

Frank and I both wrote long poems in 1953 (Second Avenue and When the Sun Tries To Go On). I had no clear intention of writing a 2400-line poem (which it turned out to be) before Frank said to me, on seeing the first 72 lines - which I regarded as a poem by itself - "Why don't you go on with it as long as you can?" Frank at this time decided to write a long poem too; I can't remember how much his decision to write such a poem had to do with his suggestion to me to write mine.

While we were writing out long poems, we would read each other the results daily over the telephone. This seemed to inspire us a great deal.

Frank was very polite and also very competitive. Sometimes he gave other people his own best ideas, but he was quick and resourceful enough to use them himself as well. It was almost as though he wanted to give his friends a head start and was competitive partly to make up for this generosity. One day I told Frank I wanted to write a play, and he suggested that I, like no other writer living, could write a great drama about the conquest of Mexico. I thought about this, but not for too long, since within 3 or 4 days Frank had written his play Awake in Spain, which seemed to me to cover the subject rather thoroughly.

Something Frank had that none of the other artists and writers I know had to the same degree was a way of feeling and acting as thought being an artist were the most natural thing in the world. Compared to him everyone else seemed a little self-conscious, abashed, or megalomaniacal. This naturalness I think was really quite strange in New York in 1952. Frank's poetry had and has this same kind of ease about the fact that it exists that is so astonishing.

April 1964

Poet Among Painters

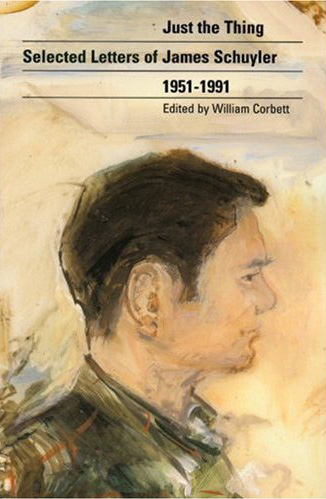

by JAMES SCHUYLER

I first met Frank O'Hara at a party at John Myers' after a Larry Rivers opening: de Kooning and Nell Blaine were there, arguing about whether it is deleterious for an artist to do commercial work. I was most impressed by the company I was suddenly keeping.

A very young-looking man came up and introduced himself (I had already read a poem by Frank in Accent, the exquisitely witty "Three Penny Opera," written either at Harvard or at Michigan.) He asked me if I had read Janet Flanner that week in the New Yorker, who had just disclosed the scandal of Gide's wife burning all his letters to her. "I never liked Gide," Frank said, "but I didn't realize he was a complete shit."

This was rich stuff, and we talked a long time; or rather, as was so often the case, he talked and I listened. His conversation was self-propelling and one idea, or anecdote, or bon mot was fuel to his own fire, inspiring him verbally to blaze ahead, that curious voice rising and falling, full of invisible italics, the strong pianist's hands gesturing with the invariable cigarette.

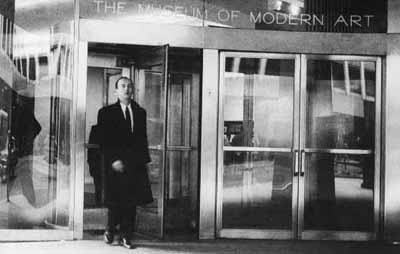

Frank told me that he had taken a job at the Museum of Modern Art, working in the lobby at the front desk, in order to see Alfred Barr's monumental retrospective of Matisse. Frank had idols (many) and if Matisse was one, so was Alfred Barr, and remained so during all of Frank's years of association with the museum. The first time I dropped by to see him, I found him in the admissions booth, waiting to sell tickets to visitors and, meanwhile, writing a poem on a yellow lined pad (one called "It's the Blue!").

He also had besides him a translation of Andre Breton's Young Cherry Trees Secured Against Hares (although he made translations from the French - Reverdy, Baudelaire - his French was really nothing much). Soon we were sharing an apartment on East 49th Street, a cold water flat five flights up with splendid views.

Frank O'Hara was the most elegant person I ever met, and I don't mean in the sense of dressy, for which he never had either the time or the money. He was of medium height, lithe and slender (to quote Elaine de Kooning, when she painted him, "hipless as a snake"), with a massive Irish head, hair receding from a widow's peak, and a broken, Napoleonic nose: broken in what childhood scuffle, I forget. He walked lightly on the balls of his feet, like a dancer or someone about to dive in the waves. How he loved to swim! In the heaviest surf on the south shore of Long Island, often to the alarm of his friends, and even at night when he was drunk and turn waspish. That was both unpleasant and alarming, since he would say whatever came into his head, giving his victim a devastating character analysis, as with a scalpel.

Frank's friends! They came from all the arts, in all troops. As John Ashbery has written in his introduction to The Collected Poems (nearly seven hundred pages of them): "The nightmares, delights and paradoxes of life in this city went into Frank's style, as did the many passionate friendships he kept going simultaneously (to the point where it was almost impossible for anyone to see him alone - there were so many people whose love demanded attention, and there was so little time and so many other things to do, like work and, when there was a free moment, poetry.)"

Then there were the events. Frank was in love with all the arts: painting and music and poetry, almost all movies, the opera and particularly, the ballet. Then there were the parties and the dinners and old movies on late night TV. When did the poems get written?

with franz kline at the cedar tavern in 1959

with franz kline at the cedar tavern in 1959

One Saturday noon I was having coffee with Frank and Joe LeSueur (the writer with whom Frank shared various apartments over the years), and Joe and I began to twit him about his ability to write a poem at any time. Frank gave us a look - both hot and cold - got up, went into his bedroom, and wrote "Sleeping on the Wing," a beauty, in a matter of minutes.

Then, his book Lunch Poems is literally that. Frank became a permanent member of the International Program at the Museum of Modern Art at the behest of the then-director, Porter A. McCray. I later wended my way into the same department and had ample opportunity to observe Frank in action.

He would steam in, good and late and smelling strongly of the night before (in his later years, his breakfast included vodka in the orange juice, to kill the hangover and get him started). He read his mail, the circulating folders, made and received phone calls (Frank suffered a chronic case of "black ear": I once called him at the museum and the operator said, "Good God!"; but she put me through). Then it was time for lunch, usually taken at Larré's with friends. When he got back to his office, he rolled a sheet of paper into his typewriter and wrote a poem, then got down to serious business. Of course this didn't happen every day, but often, very often.

with patsy southgate & kenneth koch It has been suggested that the museum took too much of so gifted a poet's time. Not really: Frank needed a job, and he was in love with the museum and brooked no criticism of it. At times, of course, he became impatient with the endless and often seemingly petty paperwork connected with assembling an exhibition, and I have seen him come from an acquisitions meeting with smoke coming out of his ears (he never divulged a word of what passed at these highly confidential affairs). But Frank had the rare gift of empathy for the art of any artist he worked with; he understood both intention and significance. And he was highly organized, with a phenomenal memory. When I say, "he got down to work," I mean it; he worked, and he worked really hard.

with patsy southgate & kenneth koch It has been suggested that the museum took too much of so gifted a poet's time. Not really: Frank needed a job, and he was in love with the museum and brooked no criticism of it. At times, of course, he became impatient with the endless and often seemingly petty paperwork connected with assembling an exhibition, and I have seen him come from an acquisitions meeting with smoke coming out of his ears (he never divulged a word of what passed at these highly confidential affairs). But Frank had the rare gift of empathy for the art of any artist he worked with; he understood both intention and significance. And he was highly organized, with a phenomenal memory. When I say, "he got down to work," I mean it; he worked, and he worked really hard.

James Schuyler died in 1991. You can purchase Homage to Frank O'Hara here.

with helen frankenthaler

with helen frankenthaler

"Why I Am Not A Painter" - Frank O'Hara (mp3)

"Ave Maria" - Frank O'Hara (mp3)

"Having a Coke With You" - Frank O'Hara (mp3)

"Poem/Poem" - Frank O'Hara (mp3)

at the club I loved him very much so quickly I wish as I'm sure everyone else does who had ever known him that we hadn't lost him.

at the club I loved him very much so quickly I wish as I'm sure everyone else does who had ever known him that we hadn't lost him.

Charles Olson